Texas law allows police to keep details about deceased suspects confidential

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/f0b59a785864308c06beda4ee0577433/Denied_Featured_Image_TT.jpg)

Editor's note: This investigation, "Denied," was produced by KXAN-TV in Austin.

*Correction appended.

As alarmed customers stared out the windows of a downtown Austin restaurant and beer pub during lunchtime that day in January 2017, Austin Police Officer Iven Wall parked his patrol car in the middle of the street, jumped out and radioed for help.

“He’s got a gun, and he’s in the back seat,” Wall said to dispatch.

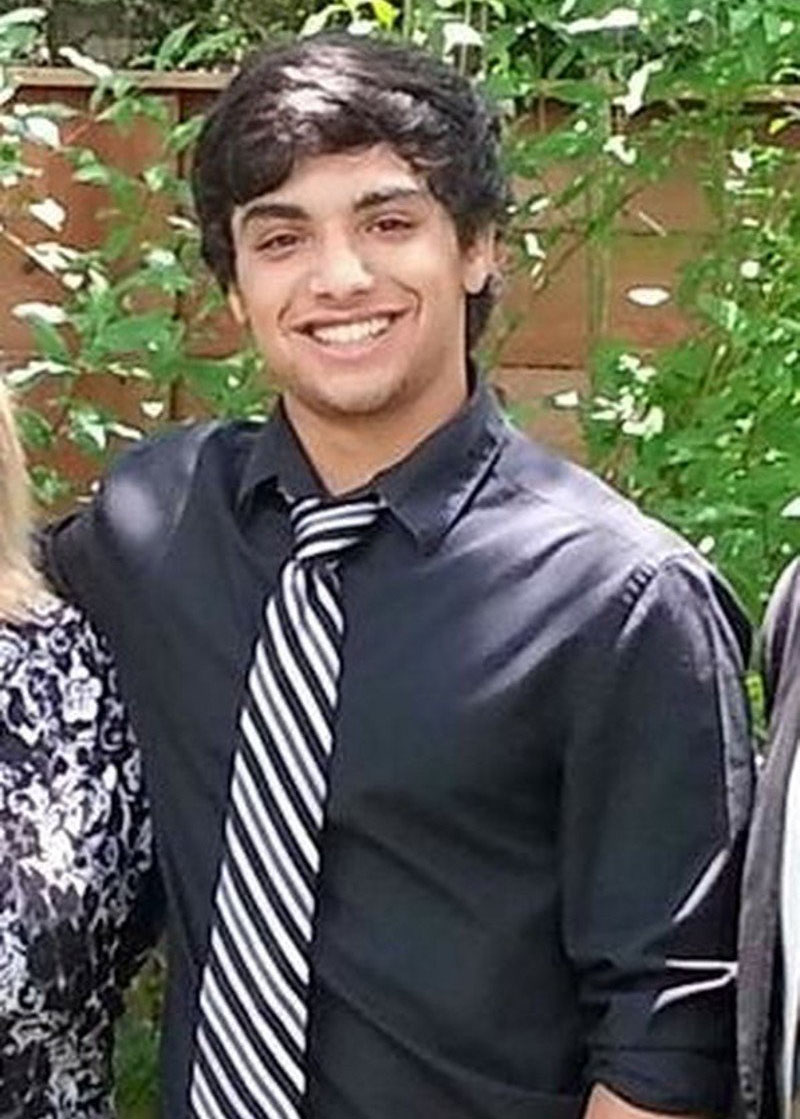

Zachary Anam, a 19-year-old shoplifting suspect who was handcuffed in the back of Wall’s cruiser and bound for police headquarters, had managed to retrieve a pistol and apparently told Wall he was suicidal.

“He’s got it to his head,” Wall continued.

Other officers arrived to block off traffic at the intersection of Fifth and Lavaca streets. Barely four minutes passed before a loud pop echoed off the nearby buildings.

“Shots fired inside the car, inside the car,” one officer radioed.

“Start EMS,” said another. “I can see in the reflection, we’ve got blood.”

Anam died later that day – Jan. 8, 2017 – surrounded by family at a hospital, the victim of a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head. He had been kept on life support for hours, as medical teams worked to remove the organs his family had decided to donate.

“The family had a lot of questions … what had occurred and how their son had a firearm while in police custody,” an investigator’s report noted, adding that Anam’s father “said the last time they had communicated with their son was via text on Christmas Day when he had (texted) ‘Merry Christmas I love you. I’m sorry.’”

Surveillance video of the arrest, dash camera video of the scene and a video recording inside the car captured details that would answer those questions from Anam’s family, the media and a confused community.

But more than a year since officially closing the investigation, Austin police still refuse to release them to the public.

Legal loophole

When KXAN investigators requested video in Anam’s case, Austin police cited an exemption to the Texas Public Information Act that gives law enforcement agencies discretion to withhold information in closed cases if a suspect did not go through the court process.

In the past decade, the department has used that exemption to block more than 70 public information requests. Each time a requester has challenged such a denial, the city’s legal department says the Texas Attorney General’s office has erred on APD’s side, just as it had with KXAN’s request.

“Police departments that really want to do their jobs well understand that public trust is a huge part of it, and transparency is what leads to public trust,” said Kelley Shannon, executive director of the Freedom of Information Foundation of Texas, a nonprofit group advocating for open government. “If you close off records and don’t tell the public what you’re up to … people wonder what you’re doing.”

Before the mid-1990s, most law enforcement records in Texas were considered public, except those that might hinder ongoing prosecution or an active police investigation. But a 1996 Texas Supreme Court case opened the door for law enforcement to keep closed cases private.

Following that ruling, state lawmakers crafted a new statute to specifically withhold from the public “information that deals with the detection, investigation, or prosecution of crime only in relation to an investigation that did not result in a conviction or deferred adjudication.”

One argument for the new law was protecting the privacy of people who were cleared of a crime. Jennifer Laurin, a University of Texas at Austin law professor, said that might include people who were arrested or pulled over during a traffic stop “who don’t want that episode in their life brought up again after it’s over.”

A survey of other states’ public information laws revealed Texas’ measure may be unique in giving police the choice to release or withhold closed case files.

“It is possible that [Texas] law enforcement agencies could invoke the public information act exemptions to withhold information that they know would be damaging to the law enforcement agency or to a particular officer,” Laurin said.

That is especially concerning to Shannon’s group when a suspect dies in police custody. Because the deceased person never enters the court system, police can permanently withhold information in such cases.

“The person is dead,” Shannon said. “They're not going on to trial. We feel like there are many, many records out there that would shed light on what happened – maybe even show the police acting very properly. But if those records aren't released, how will we ever know?”

Legislation to release records failed

A KXAN analysis of Texas attorney general data revealed more than 2,700 people have died in Texas police custody since 1978. That number does not include those who have died in jail or prison.

In 2017, state lawmakers considered House Bill 3234, aimed at amending the Texas Public Information Act and requiring police to release closed-case information if the suspect is dead or agrees to its release.

“The intent of the bill isn’t to cause any issues in an active case or create any sort of chilling effect,” state Rep. Joe Moody, D-El Paso, told members of the House Government Transparency and Operations Committee in April 2017 at the state Capitol. “What we’re dealing with here are closed cases that fall into an exception that they shouldn’t have.”

Moody, a former prosecutor, pointed to high-profile examples like the shooting of five Dallas police officers in the summer of 2016. The shooter was killed before he could be brought to justice, “meaning the records related to what happened that night are now permanently exempt from disclosure.”

Legislators listened to testimony about several other cases, learning how law enforcement has used measure for decades statewide to deny records from reporters, lawyers and even families seeking answers and, sometimes, evidence for legal action.

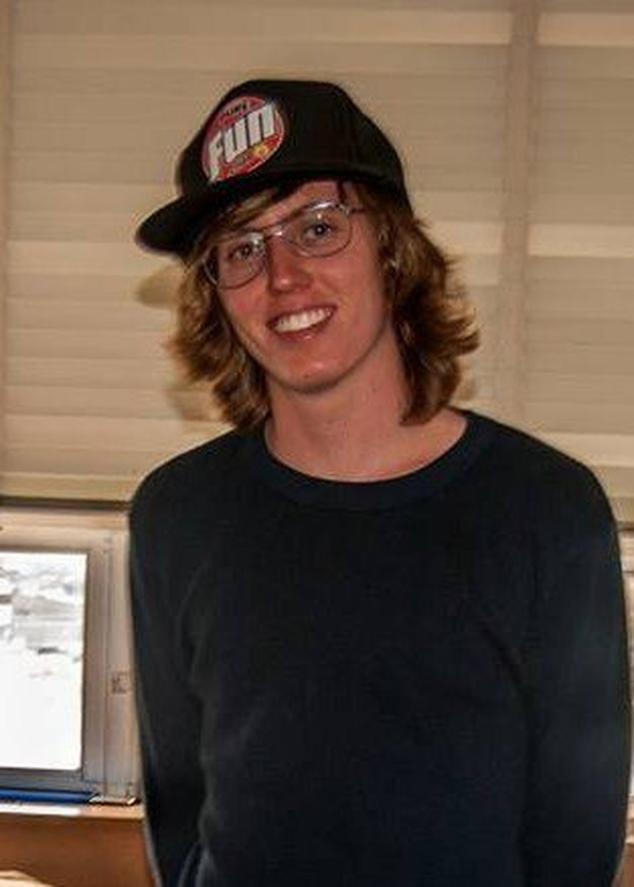

Among those testifying was a couple from Paris, a small city in North Texas. Robert and Kathy Dyer told lawmakers how police in nearby Mesquite had denied their request for records related to the 2013 in-custody death of their 18-year-old son, Graham. The attorney general had also agreed with police in that case.

“Nothing’s going to bring Graham back,” Robert Dyer told the panel. “But if I can do anything to prevent anything like this from ever happening again, I’ll be up here [at the Capitol] every day.”

Committee members voted unanimously in favor of the legislation, but it failed to progress for a vote before the full House before the 2017 legislative session ended.

A family’s fight

Mesquite police called Graham’s parents in the middle of the night on Aug. 14, 2013, telling them the college student had seriously hurt himself during an arrest. When Robert and Kathy Dyer arrived at the hospital, police swarmed the hallway outside their son’s room, telling them he was in “serious trouble.”

Their son was unresponsive and died hours later. A medical examiner said he suffered blunt force trauma to his head, self-inflicted injuries. The autopsy listed his death as an accident.

The Dyers wanted to know exactly how Graham died. Police told the couple Graham was high on LSD. Picked up for public intoxication, he had also been charged with resisting arrest and assaulting a police officer, having bitten one of their fingers, according to the arrest report.

A week after the funeral, his parents asked for more information. The incident had been captured by surveillance cameras, police dash cameras and another camera inside the patrol car transporting Graham to jail. When police cited that public information exemption and refused to release the footage and other records, the Dyers wondered why.

“It’s just so unfair to a parent who’s lost a child to tell them, ‘Well your child wasn’t convicted, so you can’t have the records,’” Kathy Dyer told KXAN. “He wasn’t convicted because he’s dead. It just hits you like a ton of bricks.”

Robert Dyer added, “You know, as soon as they clamp down like that, it’s like, well, maybe there’s something there.” The Mesquite Police Department has maintained there was no wrongdoing by its officers, though the city declined an interview with KXAN.

The couple hired an attorney to file a civil rights complaint in federal district court based on the little evidence they had – mostly medical records and accounts of that night from their son’s friends. But a judge ruled the Dyers lacked enough proof for an excessive force claim and dismissed the case.

“It’s been a long, long process. A hard process,” Kathy Dyer said. “It’s not made to be easy. The system is not set up to be easy for a family to have any recourse.”

She had also been researching options on her own, discovering the FBI could investigate citizen complaints of civil rights abuses. Months after making that request, the agency told her it could not bring a lawsuit against Mesquite police based on a review of evidence in the case.

However, Kathy Dyer realized her plea for help might have opened a door to finally obtain the evidence. If the FBI had truly investigated her son’s death, it would have collected those details – and that federal agency was not bound by Texas law.

Through the federal Freedom of Information Act, she asked the FBI to release those records. Within months, the video arrived, and the Dyers said it did not match what police told them happened.

The footage, provided by the family’s attorney, shows police tasing Graham Dyer multiple times after he rushes at an officer. It later shows him in the back seat of a patrol car with his hands and feet bound – but without his seatbelt fastened — thrashing around and slamming his head roughly 50 times against the window and the cage separating him from the front seat.

In the video, an officer stops the car to tase him again. An officer punches him and later exclaims, “I’m going to kill you.” As Graham Dyer screams, officers turn him over and repeatedly shock him directly on his testicles.

The final images show Graham’s limp body being dragged out of the vehicle onto the sally-port floor before being carried into the jail. Police records show more than two hours passed before an ambulance was called.

The case never went before a grand jury. No officers were disciplined. However, obtaining the video gave the Dyers enough evidence to revive their federal lawsuit, which the judge has allowed to proceed.

“It’s one of the few things you can do,” Kathy said. “You can bring that financial pressure to bear. They have to be considering, ‘What can we do to not end up in this situation again?’ ”

The Dyers have also vowed to help reintroduce legislation next year that would close the loophole allowing police to deny records in cases like their son’s.

“You know, he doesn’t have a voice anymore, and we do,” Robert Dyer said.

Community concerns

“You may be a very reputable journalist working for a very reputable news outlet,” Austin’s interim police chief, Brian Manley, said when asked about his agency’s denial of KXAN’s request in the Zachary Anam case. “But, if we agree to release it to you, we have now lost all ability to withhold it from anybody who makes that request.”

Manley explained he wanted to protect Anam’s family from having to see such graphic footage of their loved one.

“Our philosophy is that we should put out all of the information that we can – with a few caveats,” he said. “And this particular issue is one.”

Manley said if the Legislature removed the exception allowing police to withhold records in cases like this, it would also remove their “ability to really look at cases on a case-by-case basis."

“A lot of times what goes into that is there’s a lot of competing interests,” he explained. “I absolutely understand this community has an interest in what’s going on within the city, and this is an agency that believes in transparency.”

The arrest was just the latest for Anam, who had been charged with several crimes in the preceding year, including burglary and drug possession. Police interviews with those who knew Anam indicated a history of substance abuse and mental health concerns.

On the day Anam died, Austin police responded to a shoplifting call from security personnel at a Macy’s in a southwest Austin mall. According to a police report, store security had detained him after catching him trying to cut tags off clothing, a watch and a pair of earrings and walk out of the store.

Wall, the arresting officer, found a “crystal-like substance” he believed to be methamphetamine inside a folded-up dollar bill while placing the teen in custody, according to the report.

But he missed a pistol – a Glock semi-automatic .380 – hidden under Anam’s waistband.

In an audio recording of Wall’s internal affairs interview, the officer admitted he only patted down the suspect instead of conducting a more thorough inspection for weapons.

“When the officers pulled him out of the car, I saw it…” Wall said in the interview. “I saw an inside-the-waistband holster stuffed down inside his pants.”

Wall received a 20-day suspension, and the case was never presented to a grand jury. At the time, Anam’s parents said they were “severely disappointed with the minimal discipline” and called on APD to retrain every officer on how to properly frisk suspects.

“Every time I open the back door of a patrol car, I think about that young man,” Wall said during his disciplinary hearing. “The disciplinary portion that’s looming over me today will be final after today, but I’ll still have to live with that.”

Disclosure: The University of Texas at Austin has been a financial supporter of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune's journalism. Find a complete list of them here.

Correction: An earlier version of this article stated Austin police have used the exemption to block about 1,900 public information requests in the past decade. Days after publication, the City of Austin informed KXAN of a miscommunication. That statistic was actually the number of total denied public information requests. The number denied under the exemption was instead more than 70. KXAN apologizes for the confusion.

Information about the authors

Contributors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.