World War One: HM Factory Gretna's vital munitions role

- Published

They called it the Greatest Factory on Earth.

Built to produce much-needed ammunition for Britain's out-gunned troops in the early years of World War One, HM Factory Gretna was a game-changer.

Its role in the war effort - and the remarkable social experiment it was part of - are told in a new custom-built museum which has just opened in the village of Eastriggs.

It's called "The Devil's Porridge" - after an explosive paste mixed there - and it has been completed just in time for the war's centenary.

The story began with what newspapers of the time called the "Shells Scandal" - the British army's chronic shortage of firepower on the Western Front.

The government's response was to order the building of a new munitions super-factory - HM Gretna - and all the social infrastructure needed to support its huge workforce.

In a field near Gretna, historian Gordon Routledge showed me some brick and concrete ruins which are pretty much all that remains of this once vast facility.

"During the First World War it was certainly the biggest munitions factory in the world," he said.

"It was designed on the earlier factories by Nobel - the original factory he built at Ardeer in Ayrshire and there were factories in South Africa.

"The Gretna factory was built on the same principle - but it was bigger."

It stretched nine miles from Dornock near Annan to Mossbank in Cumbria with 30 miles of road, 125 miles of rail track and 20,000 workers from all over Britain and its Empire.

Richard Brodie, of the Eastriggs and Gretna Heritage society, said the work was highly dangerous.

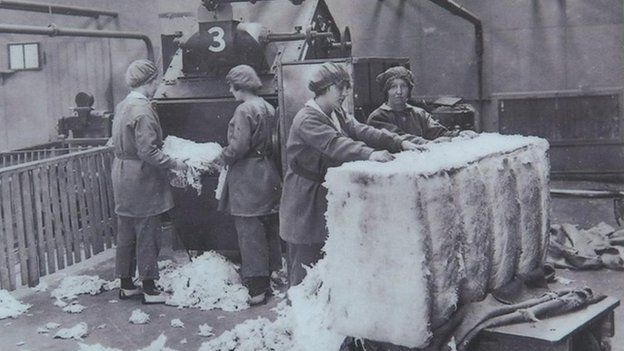

In the newly opened museum, he showed me a huge vat in which the mainly female workforce mixed cordite paste to make propellant for shells.

The particularly nasty brew was dubbed the Devil's Porridge by Sherlock Holmes' creator Arthur Conan Doyle who came here to write about the factory he code-named Moorside to protect its location.

"It was a very volatile mixture, the women were not allowed any rings or earrings in case they caused a spark and the whole thing would blow up," said Mr Brodie.

"You wouldn't work in those conditions nowadays, there would be acid fumes in the air.

"The acid would attack the girls' gums and if they were exposed to it too long, the gums would rot and their teeth would fall out."

The work was dangerous and unpleasant but thousands of the girls doing it had come from domestic service and found their new job worthwhile and rewarding.

Among their number were Annan man Jim Hawkins' three aunts - Jean, Betty and Margaret Irving.

He said it proved to be a big change for them.

"It was dangerous work with long-term hazards from chemicals but they earned a little money," he explained.

"They gained self-respect which they didn't have when they were working in domestic service."

Alongside the cordite factories, two new townships of Gretna and Eastriggs were constructed - from scratch in less than a year - to house the international workforce that flocked here and to provide their every living, social and leisure need.

Some 15,000 mainly Irish navvies were involved in the construction.

The streets were laid out garden city style and named after cities in the British Empire.

Mr Routledge said: "It was a self-contained factory community with everything at Gretna mirrored at the Eastriggs site.

"There were cinemas, churches, all these facilities were built - better than in the local area by far.

"Before the First World War there were only the marriage rooms and a few isolated farms and this township here evolved out of the war effort."

The total project was completed in record time at a cost of more than £9m - about - four times over budget - but in the way it bolstered the war effort, it may just have been priceless.

Not for nothing does Gretna still have a Victory Avenue.

"Before HM Factory Gretna was built, Britain was losing the war," said Mr Brodie.

"Lloyd George became the Minister of Munitions and this was his greatest project to provide soldiers with the ammunition they needed.

"So without HM Factory Gretna there could have been a completely different outcome to the war."

- Published27 February 2014