With Mitt Romney and Newt Gingrich now the leading contenders for the Republican nomination, the doctrine of "American exceptionalism" -- or, more precisely, President Obama's alleged lack of belief in it -- has become a key battleground in the 2012 presidential election. At a November debate in South Carolina, Romney launched a sharp attack: "We have a president now who thinks America is just another nation. America is an exceptional nation." Ten days later, Romney accused Obama's foreign policy of adhering to the view that "America's just another nation with a flag." "President Obama," he continued, "seems to think that we're going to have a global century, an Asian century." Romney's own view is that "America is an exceptional and unique nation ... we have to have an American century, where America leads the free world and the free world leads the entire world."

Gingrich, whose most recent book is entitled A Nation Like No Other: Why American Exceptionalism Matters (2011), is even more committed than Romney to placing the issue at the center of his campaign. President Obama, he asserts, "simply does not understand the concept of American exceptionalism." Worse yet, Gingrich claims that "Obama has developed a strong unease with American power," pronouncing himself a "citizen of the world," and denouncing "America's supposed transgressions in front of foreign audiences."

For Gingrich, "America is simply the most extraordinary nation in history." "This is not a statement of nationalist hubris," he insists, but rather "an historical fact." It is this very greatness that, in his view, is threatened by President Obama, whom he has repeatedly called "the most radical President in American history." As he elaborated in his 2010 book, To Love America: Stopping Obama's Secular-Socialist Machine, Gingrich believes that Obama is a committed socialist. From the federal takeover of health care to the nationalization of student loans, Obama has demonstrated, argues Gingrich, that he is dedicated to destroying the very exceptionalism that has made America great.

Though Gingrich has a Ph.D. in history and takes great pride in his status as a historian, he seems strangely unaware of the origins of the term "American exceptionalism." Ironically, this term -- now so beloved by the American right -- was invented in Moscow in May 1929 by Joseph Stalin and his comrades in the Communist International, who denounced the leaders of the American Communist Party for believing that the "universal laws" of Marxist theory needed to be adapted to the specific conditions of the United States. This belief -- the view that each country had to build its own path to Communism -- constituted the heresy of "American exceptionalism." So serious was the offense that Jay Lovestone, then the head of the American Communist Party, was summarily expelled from the party, barely escaping from Moscow with his life.

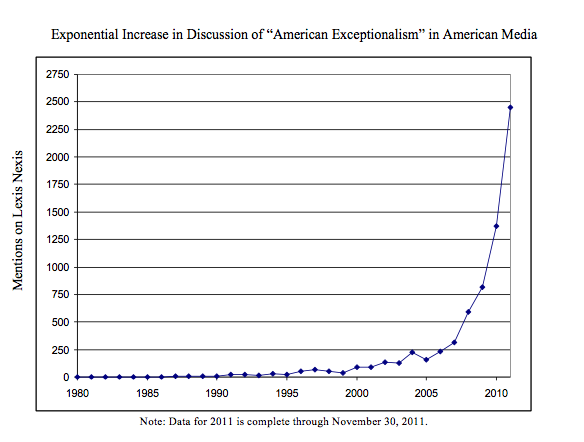

Not until decades later did the phrase "American exceptionalism" move outside rather narrow Marxist circles, and not until the Reagan years of the 1980s did it first come to be used with anything like the meaning that Gingrich now takes for granted. But the concept -- if not the term -- has deep roots in American history. From John Winthrop's 1630 oration, in which he referred to the new community he was founding in America as a "city upon a hill," to Lincoln's description of the United States, as "the last best hope of earth," the idea of America as a great nation with a unique mission has resonated widely. But what is new in recent years is that public expressions of belief in "American exceptionalism" -- which has come to mean in popular parlance that the United States is not only different from, but superior to, other countries -- has become something of a required civic ritual for American politicians. This new definition of American exceptionalism has coincided with an extraordinary increase in public discussion of the term, with references in print media increasing from two in 1980 to a stunning 2,580 this year through November:

What might be called the "U.S. as Number One" version of "American exceptionalism" enjoys broad popular support among the public. According to a Gallup poll from December 2010, 80 percent of Americans agree that "because of the United States' history and its Constitution ... the United States has a unique character that makes it the greatest country in the world." Support for this proposition varied somewhat along party lines, but not by much: 91 percent of Republicans agreed, but so, too, did 73 percent of Democrats.

For President Obama, the issue of American exceptionalism could be his Achilles' heel. In that same 2010 Gallup poll, Americans were asked which recent presidents believed that "the United States has a unique character that makes it the greatest country in the world." Reagan was highest at 86 percent, followed by Clinton at 77 percent, and George W. Bush with 74 percent; President Obama was a distant fourth at 58 percent. Obama's vulnerability on the issue may be traced in part to his response to a question in April 2009 from a Financial Times reporter about whether he subscribed, "as many of your predecessors have, to the school of American exceptionalism." "I believe in American exceptionalism," declared Obama, "just as I suspect that the Brits believe in British exceptionalism and the Greeks believe in Greek exceptionalism." Though taken out of context, the remark serves as Exhibit A for Republicans making the case that Obama does not believe in "American exceptionalism" and, by extension, in America's greatness.

The truth, however, is that Obama does believe in American exceptionalism, although his version is quite different from the one being promulgated by Gingrich and Romney. Hints of Obama's conception are visible in his full response to the Financial Times reporter's question about American exceptionalism. After noting that "the United States remains the largest economy in the world" and possesses "unmatched military capabilities," the president emphasized that Americans "have a core set of values that are enshrined in our Constitution, in our body of law, in our democratic practices, in our belief in free speech and equality, that, though imperfect, are exceptional." And in December 2007, shortly before the Iowa caucus that put him on the path to the presidency, Obama said to Roger Cohen of The New York Times, "I believe in American exceptionalism," but not one based on "our military prowess or our economic dominance."

This is a start, but not the forceful and fully elaborated articulation of American exceptionalism Obama will need in 2012, whether his opponent is Gingrich or Romney. Whoever the Republican nominee, he will almost certainly launch a frontal assault on the issue, hammering home a clear and simple version of American exceptionalism emphasizing limited government, military strength, and a commitment to maintaining the position of the United States as the world's greatest power. This vision resonates with much of the electorate.

Elements of Obama's alternative conception of American exceptionalism are already present in various speeches and public statements. This conception sees America as a land of unlimited opportunity, open to all, including racial minorities and immigrants ("in no other country on Earth is my story even possible"); a country of tolerance whose "constitutional freedoms have made our country the envy of the world"; a nation whose true strength comes from "the enduring power of our ideals: democracy, liberty, opportunity, and unyielding hope"; and, above all, a place of ceaseless innovation and an abiding sense that "anything is possible."

The president's recent speech in Kansas, in which he proclaimed the United States "the greatest nation on Earth" and the "country [where] even if you're born with nothing, hard work can get you into the middle class," suggests that he grasps the magnitude of what is at stake. His task now is to articulate his own distinctive vision of American exceptionalism, one that gives the public a clear roadmap of where he plans to take the country and how he plans to draw on America's distinctive strengths and traditions at a time of widespread fear of national decline. On his success may depend whether the Obama presidency, which began with such soaring hopes, will be cut short after just four years.