Everything But The House: Ohio's hottest startup plots a comeback

CINCINNATI – Startup Everything But The House set out to build an empire selling second-hand goods via the internet, from Murano Glass vases to vintage Harley Davidsons.

The company set itself apart by carefully appraising and authenticating real treasures, such as Andy Warhol silkscreens – and for a time, became Ohio's most valuable startup.

At its height, Everything But The House created a budding national brand: doing business in 27 cities across the United States. Annual sales were flirting with $100 million, and it was eyeing international expansion.

Celebrities used the service to relocate or refresh their homes. It was even the subject of a pilot for a potential series on HGTV last year.

Executives told employees they were going to be “the next Amazon.”

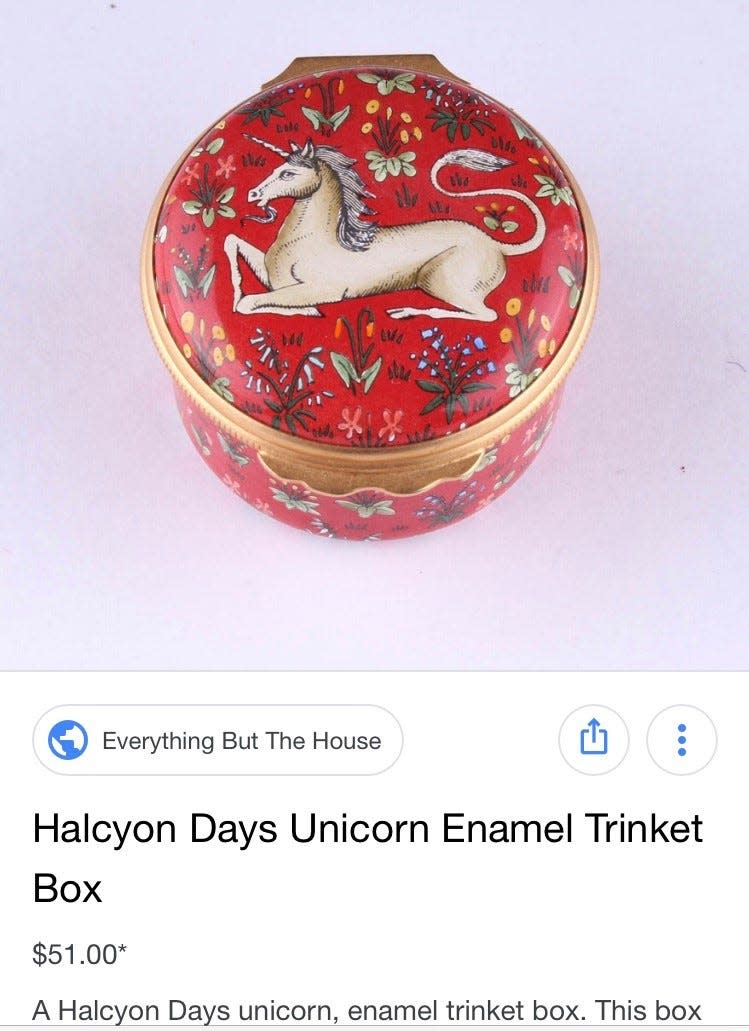

Amid soaring sales, Everything But The House even looked like it had a shot at becoming the kind of treasure coveted by all aspiring tech cities outside Silicon Valley: a start-up business that achieves a $1 billion valuation. Known in the industry as a "unicorn," such an economic breakthrough has only been achieved in a handful of cities across the country.

But behind the scenes, EBTH had runaway growing pains – and some say egos. Costs, complaints and losses were growing as fast as sales.

'Indifference to safety': US senators call for investigation of Ford Focus, Fiesta transmission decisions

Gen Z, millennials speak out: It's 'embarrassing' to rely on parents for money after 27

Then in spring 2018, three top executives – who had partnered with the founders in 2012 and lit the growth fuse – quit abruptly as EBTH began shuttering more than a dozen sites. Rounds of layoffs ensued, costing hundreds their jobs.

Those same executives have since been accused in a civil fraud lawsuit of engineering a private sale of company stock to an investor while withholding details of its deteriorating financials. The company is also a defendant in the lawsuit.

Welcome to the glamorous dot-com economy.

Creating viable tech ventures and courting those high-paying jobs are Middle America’s newest obsession as demonstrated by the 2017-2018 bidding frenzy for Amazon's second headquarters. More than ever, it also looks tantalizingly up for grabs as San Francisco, Silicon Valley and other traditional tech hubs grapple with unprecedented growth fatigue.

Cincinnati – and other cities – all want a bigger piece of the fast-growing tech sector.

Last fall, Forbes labeled Cincinnati one of “The Top 10 Rising Cities For Startups,” noting the Queen City had attracted more than $100 million in venture capital investment in 2018.

Today, Everything But The House has new management and is looking to reboot growth.

New CEO Scott Griffith says the business is on track to turn its first-ever profit within 12 months and sales could break $100 million for the first time in 2020.

He’s looking to hire a No. 2 executive, a chief operating officer. The company also just moved into snazzy (albeit smaller) headquarters in Cincinnati’s trendy Over-The-Rhine neighborhood – in just the sort of digs designed to lure creative, tech-savvy workers with an appetite for lattes and stock options.

But it's been a bumpy ride: the company now employs 400 nationwide, including 200 in Cincinnati – down from 1,000 with 400 local employees two years ago.

"Often when you see tech IPOs where everyone is smiling ... people think they just got on the escalator and it went straight up – that's almost never the case," Griffith told The Enquirer. "Startups are more like cats with nine lives ... there have often been several near-death experiences."

The story of Everything But The House is a tale of inspiration, ambition, sweat equity and hubris.

EBTH hopes it’s eventually about redemption.

The business of buried treasures

Lorraine Gibbs, a 58-year-old retired human resources director, was recently visiting Everything But The House’s showroom in the Blue Ash processing center perusing artwork at one of the company’s “preview sales” before a big auction.

“I’m always looking for neat things – they pre-certify everything, so I’m not worried about buying knock-offs,” Gibbs said.

She has been a customer for years, but she's used them to sell items, too. When she retired, she decided to part with a Louis Vuitton workbag. She got $900 for the bag that cost her $2,200 new.

Everything But The House’s roots are in auctions and estate sales. The company was founded in 2007 by collectors Jacquie Denny and Brian Graves who began selling items online in 2008.

Denny got into the industry, inspired by a bad experience following the death of a beloved great aunt. A few valuables were sold at auction, but the rest of her estate generated little cash.

"One bad experience got me thinking – something was missing and I realized there was a market for a better service," Denny told The Enquirer.

Denny ran an auction and estate business in the 1990s and early 2000s, winning raves for her white-glove service. But the start of the millennium was a tough time in the industry as Baby Boomers mostly downsized and new digital competitors eBay and Craigslist cannibalized the lower-end of the market.

Auctions were at the mercy of how many bidders attended sales.

In 2006, Denny met Graves, who quips he became an amateur dealer to support his own “habit.” Graves, who worked in tech management and development for UPS and later Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, suggested starting auction business on the internet with a much larger bidding pool. .

"It was a leap – we weren't sure it would work, but we thought there had to be a better way," Graves said.

'It was fun – pure adrenaline'

The company started by focusing on helping customers who needed to clear out houses stuffed with stuff – empty nesters looking to downsize, a grieving family too overwhelmed to pick through a loved one’s estate or a rising Procter & Gamble executive moving to Singapore. Everything But The House sold all your stuff (except the house).

Every item sold, whether it's a baseball card or a car, starts bidding at $1 online.

Specifically, EBTH would go to a home and scour for in-demand items and unique treasures that would command strong online bids. They handled billing, shipping and donating or discarding items not for sale. Crews even cleaned houses to be move-in ready.

EBTH provided this extra service but still charged less than the traditional 50% cut demanded by consignment shops.

The business won raves from customers who told tales of forgotten watercolor prints sitting in attics that turned out to be lucrative finds spotted by EBTH’s appraisers.

Business was great – sales doubled for three straight years and kept growing.

EBTH hired a handful of workers and contractors. It didn’t bother to advertise for the first four years of its venture as word-of-mouth spread.

It got calls about expanding or franchising. Nobody else in the country seemed to be doing quite what EBTH did.

"It was fun – pure adrenaline, a magic time seeing the growth and how people shared (referred) our service with neighbors and bidders," Denny recalled. "My dining room was the mail room: I mailed packages sometimes until 2 or 3 in the morning."

But as those early years stretched on, it was clear something had to change: Denny and Graves were each working 100-hour weeks.

Ohio's most valuable startup

Denny and Graves were looking for some way to keep the business expanding – but also catch a breath.

In 2012, they met Andy and Jonathan Nielsen and their partner Michael Reynolds. The Nielsens had recently completed a real estate venture and were looking for a new investment.

Denny and Graves were impressed by the Nielsens, who came from a prominent local business family. They were the sons of Chip Nielsen, who that year would take the helm as CEO of leading commercial real estate development firm Al. Neyer (he's now the CEO of Newtown, Ohio, confectioner Doscher’s Candy Co., maker of the French Chew, a Cincinnati favorite). Andy was also working on an MBA from Xavier University.

At that time, EBTH's founders had a business employing nearly 20 workers and contractors, generating $5 million in annual revenues and on track to generate $7 million in 2013.

After five years under the founders, Andy Nielsen articulated a plan for how to systematically grow the business.

"Andy was just a ball of energy. He had vision, he knew what the next steps should be," Denny said. "When you're in the middle of running a business, you don't have time to step back and develop all that."

Nielsen's team agreed to buy a majority stake in EBTH for an undisclosed amount. The founders remained active in the company – and still are, but Nielsen took the helm began to pursue growth and venture capital.

"We felt we had something special. Our intention was to become a national powerhouse," Nielsen told The Enquirer. "We had the opportunity to take the business national and become a dominant player."

The Nielsen team persuaded East Coast venture capital funds, led by Spark Capital in Boston and Greycroft in New York City, to invest money in the business. Nearly $85 million was raised in three stages of investing between 2014 and 2016.

Everything But The House began setting up shop in other cities in the Midwest, then on the East and West Coasts. Sales soared as operations expanded rapidly.

Team Nielsen didn't just sell its vision to investors.

The growing company began to turn heads, nabbing splashy write-ups or high-profile mentions in Fortune, CNN Money, Forbes, The Wall Street Journal, Glamour, Town & Country and People.

At the height of Everything But The House’s visibility, it handled auctions for celebrities looking to downsize – like Susan Lucci in March 2017, who sold hundreds of personal items from her closet: including a black straw hat she wore to the Kentucky Derby (when she was photographed behind Queen Elizabeth) and the gown she wore the night she met the Rat Pack in the 1970s.

In 2017, Everything But The House was declared Ohio's most valuable startup (worth nearly $215 million) and sales were expected to surpass $100 million.

@Nielsen_Andy talks #EBTH on @bizrockstars today. pic.twitter.com/8fVdCDMmdS

— Everything But The House (@EBTHofficial) March 8, 2017

Still, there were growing pains.

Graves admits he quietly had misgivings about the company's breakneck growth but believed at the time that was the price he paid when the Nielsens came on board.

The Nielsens' didn't sell everyone on their vision.

As told to anonymous employer-review web site Glassdoor, the rap on the young management team was that it was a couple of overgrown frat boys wanting to play tech entrepreneurs but didn't have a firm handle on operations.

Ground-level workers griped about too much focus on fast growth and not enough on quality control. Customer service was spotty. Items were damaged. Management was inattentive.

Cracks as growing pains persist

Cracks began to appear in Everything But The House's performance as it continued to chase a national growth strategy.

Despite its ambitions to become the next Amazon, Everything But The House struggled to fix one of the most basic problems for an e-commerce business: shipping.

Starting in 2016, Nielsen and his crew moved to a centralized nationwide processing system that operated in Blue Ash. EBTH’s far-flung locations began trying to grow sales at all costs by throwing as much stuff on trucks to Cincinnati.

Costs soared. So did breakage of fragile items.

Customers howled at huge shipping fees even on modest orders and poor service.

Almost half of the 50 consumer complaints logged against EBTH with the Ohio Attorney General's Office were in 2017. Most were referred to the Better Business Bureau, which has also logged hundreds of complaints against the company.

“I was told that even though this product was located in Blue Ash it could not be picked up – I live less than one mile from this office,” Sharonville resident Jack Scheidt told authorities after he won the bid on a Pier 1 wine rack for $17 – but he was slapped with a $38 shipping charge. “I feel this has been nothing but a money grab and feel robbed by a company I entrusted with my credit card.”

Behind the scenes, there was a growing dispute over growth plans.

Griffith, now 60, was added to Everything But The House's board of directors in early 2017 as the company grew larger and more complicated.

He was a tech veteran. From 2003 to 2013, he ran Boston-based Zipcar (which rents high-end vehicles by the hour or day via mobile phone) as it grew from a small company with $2 million in sales to $300 million in sales. He shepherded it through a 2011 IPO and later a $700 million sale of the company to Avis Budget Group.

Griffith's role was to offer Nielsen, the first-time CEO, seasoned advice. He was the first independent director on the board not representing any of the investment firms bankrolling the expansion.

But the board quickly grew restless with the Nielsen team's strategy as 2017 wore on.

Nielsen trimmed a handful of cities and dozens of jobs from Everything But The House's operations, but the board didn't think Nielsen was getting the company's costs and other issues under control, Griffith said.

“Pride and ego slowed senior management's reaction time and by (early) 2018 the board had to force a change – including bringing in new management,” Griffith said.

Nielsen said Everything But The House's rapid growth started with his team and investors agreeing on a long-term plan, but in the final months of his tenure that changed.

"When we first took on venture capital, we were aligned," Nielsen told The Enquirer. "When we agreed to recruit Scott, we had a different strategy."

Nielsen declined to elaborate. Both Griffith and Nielsen stress the former CEO was not fired. He was offered a role at the company to be determined later, but he decided to leave instead.

Griffith was named the new CEO in March 2018.

A round of mass layoffs began in late April. EBTH cut more than 200 Cincinnati workers as the company sought to stop its bleeding.

In December, EBTH cut more jobs and markets. It declined to spell out how many employees were let go, but documents obtained by The Enquirer show it was about another 200.

Even after team Nielsen left, Everything But The House has had to contend with issues in its wake.

In early 2017, the Nielsens, Reynolds as well as Denny and Graves agreed to sell some of their stock.

At the start of those negotiations, an investor was provided partial financial data for 2016. The $900,000-sale was closed in January 2017.

In a civil fraud lawsuit filed early this year, the investor claims management withheld updated financial information until after the stock sale closed – an accusation the Nielsens and Reynolds deny in court filings.

The investor claims they wouldn't have paid as much with better financial information.

Everything But The House, which is also listed as a defendant in the case, argued in court filings the company was not a party to the disputed stock sale and claims against it should be dropped.

Jonathan Nielsen, did not respond to calls seeking comment. All other parties in the pending lawsuit, including the investor, Griffith, Andy Nielsen and Reynolds declined comment.

Reynolds is now CEO of a Chicago-area nursery and landscape supply company. Andy Nielsen was reached at candy company now run by his father in Newtown.

New leadership steps in

Griffith says Everything But The House's woes came from growing too quickly. While its Cincinnati operation had been profitable, the company didn't create a common "playbook" for its other locations to follow – something Griffith has sought to correct.

Griffith has decentralized most of the processing of incoming items, which has lowered operating costs. Smaller, high-value items, such as artwork or jewelry, that need sophisticated appraisals are still shipped to Cincinnati. But a second-hand sofa in Boston is going to be processed and sold in Boston.

After closer study of its clientele, Everything But The House has played down its estate sale-roots having discovered its business has evolved. Two-thirds of products sold now come from customers only selling a few items at a time, via consignment.

People looking to liquidate larger inventories of items due to a death, divorce or move remain an important but smaller part of the company's business.

The company is also looking to align itself with an emerging retail niche called "re-commerce," which deals in second-hand goodies that appeal to millennial consumers and includes players such as The RealReal (luxury resale items) and thredUp (used fashion for sale).

Everything But The House now bills itself as the "Marketplace for the Uncommon" items.

Despite slashing 21 of 27 locations in the last two years, Griffith says sales are on track to exceed previous revenues that peaked at $90 million in 2017.

The company is approaching those sales levels from the six remaining operations in Boston, Chicago, Charlotte, Columbus, Dallas and its native Cincinnati.

Griffith said EBTH will consider expanding its operations to other cities again once it's profitable. He added:

"I'd say the world doesn't need another unicorn that hasn't figured out how to be profitable."

EBTH, the tech gold rush and what it means for Cincinnati

EBTH's bid for growth happened amid Cincinnati’s – and other cities’ – efforts to court technology jobs. A majority of America’s fastest-growing major cities have thriving tech scenes.

For example, Austin, Texas – anchored by tech giant Dell and hometown to unicorns HomeAway, Mozido and Kendra Scott – surpassed Cincinnati as America’s 27th-largest metro economy in 2016.

Cincinnati's budding tech landscape has nabbed some national notice – last fall it was named No. 6 on a Top 10 list by Forbes of “rising cities for startups” (outside the traditional coastal cities that have so far dominated the sector) that was vetted by (former America Online CEO) Steve Case’s investing firm Revolution LLC.

Currently, Cincinnati’s tech sector is dominated by big companies (dubbed “BigKos” by local observers), such as Kroger’s 84.51 consumer insights subsidiary as well as Fifth Third Bank's and Great American Insurance's digital presence. Other big employers are a mix of IT services provided by Cincinnati Bell and service behemoths, such as India’s Tata Consultancy Services and France’s Capgemini (which controls Dayton-based Sogeti USA).

What’s missing is a homegrown independent tech business that has grown into a noteworthy employer and achieved an outsize valuation.

Economic development officials say minting a locally-based tech company with several hundred employees would be the milestone that could speed the city’s transformation into new employment destination: a city where young tech talent takes a job, confident that he or she will find another local position in a volatile sector.

Aside from Everything But The House, the Cincinnati region’s most-prized tech startup is Lisnr, an ultrasonic data company that transfers encoded information using inaudible sounds. Industry-tracker PitchBook values the company at nearly $70 million and the company employs three dozen workers.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Everything But The House: Ohio's hottest startup plots comeback