By the time I reached my late 20s, I was desperately looking for a way out of Beijing. From 2001 onwards, the city was consumed by preparations for the 2008 Olympics. Every bus route had to be redirected. Every building was covered in scaffolding. Highways were springing up around Beijing like thick noodles oozing from the ground, with complicated U-turns and roundabouts. The city was surrounded by a moonscape of construction sites. Living there had become a visual and logistical torture. For me, as a writer and film-maker, it was also becoming impossible artistically, with increasing restraints placed on my work.

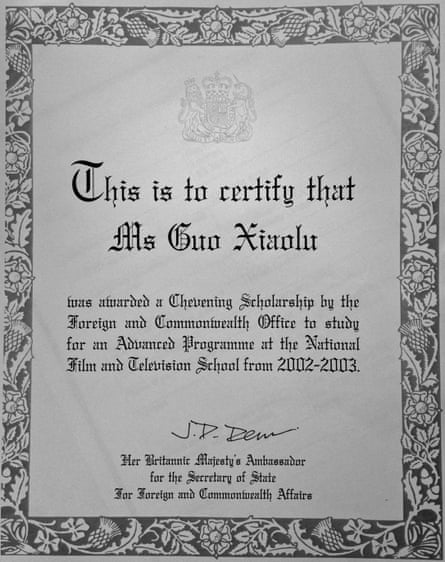

The opportunity to leave came sooner than I could have hoped. I heard that the Chevening scholarship and the British Council were looking for talent in China. I had never heard of Chevening. Someone told me it was a large historical mansion in Kent. My mind was instantly filled with images from The Forsyte Saga – one of the most-watched English television programmes on the Chinese internet. The wealthy housewives of Beijing in particular loved the fancy houses and rich people dressed in elegant costumes riding about on white horses. So I applied as a film-maker.

Eight months later, after many stressful exams, the British Council in Beijing called me in. “Congratulations! You are one of three people in China this year who’ve won the scholarship! You beat 500 other candidates!” The English lady brought me a cup of tea with a big smile. She also handed me back my passport with a UK visa in it.

When I told my parents the news, they were rather surprised, but both thought it sounded like a great opportunity. “Your father says he is very proud of you!” my mother said. “All your years of studying now make sense.” Then she added: “You said the scholarship is from England. Do you mean Great Britain?”

“Yes. Great Britain,” I confirmed.

“That’s great. Greater than United States, right?” my mother said, drawing her conclusions from her Maoist education of the 1960s. But I knew that she had no idea about either Britain or America. The only thing she knew about those countries was that they were in the west. “You should take a rice cooker with you. I heard that westerners don’t use rice cookers.”

I remember very well the day I left China. It was 1 April, and the Beijing sandstorm season had begun. I dragged my luggage towards the subway, choking in the sandy soup. This was my chance to escape the world I had grown up in. But that world was trying one last time to keep me.

“I will be walking under a gentle and moist English sky soon,” I said to myself. “It nurtures rather than hinders its inhabitants. I will breathe in the purest Atlantic sea air and live on an island called Britain.” All this was destined to be nothing more than a memory.

When I arrived at Heathrow, there was no one to pick me up, and all I had was a reservation letter for a student hostel near Marylebone station in central London. Dragging my luggage, I jumped into a taxi. As I looked out at the streets through the rain-drenched window of the taxi, it smelled damp and soggy. The air clung to my cheeks. The sky was dim and the city drew a low and squat outline against the horizon: not very impressive.

We travelled slowly, through unfamiliar, traffic-jammed streets. Everything felt threatening: the policemen moving about the street corner with their hands resting on their truncheons, long queues of grey-faced people at bus stops but no one talking, fire engines shooting through the traffic with howling sirens.

I realised that I knew nothing about this country at all. I had planted myself in alien soil. And, most of all, my only tool of communication was a jumble of half-grammatically-correct sentences. In China I had learned that the population of Britain was equal to that of my little province, Zhejiang. Perhaps it was true, since the streets didn’t look that grand, especially the motorways, which were even uglier than the ones in China. Everything was one size smaller, or even two. Still, here I was. As the Chinese say, ruxiang suisu – once in the village, you must follow their customs.

Before I left China, I was desperately looking for something: freedom, the chance to live as an individual with dignity. This was impossible in my home country. But I was also blindly looking for something connected to the west, something non-ideological, something imaginative and romantic. But as I walked along the London streets, trying to save every penny for buses or food, I lost sight of my previous vision. London seemed no more spiritually fulfilling than home. Instead, I was faced with a world of practical problems and difficulties. Perhaps I was looking for great writers to meet or great books to read, but I could barely decipher a paragraph of English.

Still, in my naive mind, I was convinced I would find an artistic movement to be part of, something like the Beat generation or the Dadaists of the old Europe. But all I encountered were angry teenagers who screamed at me as they passed on their stolen bikes and grabbed my bag – they were the most frightening group I had ever met in my life. Before I came to England, I thought all British teenagers attended elite boarding schools such as Eton, spoke posh and wore perfect black suits. It was a stupid assumption, no doubt. But all I had to go on were the English period dramas that showed rich people in plush mansions, as if that was how everyone lived in England.

In the evenings, I hid my long hair in my coat and walked along the graffiti-smeared streets and piss-drenched alleyways, passing beggars with their dogs, and I asked myself: “So is this what the rich west is really like?” If that was the case, I wanted to cry. Cry for my own stupid illusions. What an idiot I was. Now I realised there had been some truth to my own country’s communist education: the west was not milk and honey.

After the hostel in Marylebone, I had to move to Beaconsfield in Buckinghamshire, 20 miles from London. There were only two big buildings in the town: a supermarket called Tesco and the National Film and Television School, where I was to spend a year studying documentary film directing.

I felt like a complete alien in Beaconsfield. I was told that this was the richest village in all of Britain. For a Chinese person, “village” is synonymous with peasants, rice paddies and buffalos. Here, every home was surrounded by trimmed rose bushes – yellow roses in the front garden, red in the back. And everyone seemed to own a pair of cars, parked alongside their house. It was not quite The Forsyte Saga, but almost. If you walked out of the village, there were neither rice fields nor farmland to be seen. Instead, a car factory lay on the outskirts, alongside warehouses with trucks delivering goods to Waitrose or Sainsbury’s.

Most students commuted from London, so I was a rarity in Beaconsfield. And on the weekends, when I went out looking for company, I found the village absolutely dead. The only place with an open door was a brightly lit pub called the Old Swan, where I used to spend my afternoons. I liked English pubs because they had a particular smell that reminded me of my mother’s silk factory in Wenling, with its heavy scent of steam, stale air, human sweat and scorched protein.

I’d go in just after the Old Swan opened and read and write. “A cup of hot water without a tea bag please,” I would say. The woman behind the counter began to take this as a sort of weird insult, knowing that I would be sitting in the corner for hours. I learned that I needed to be a good customer, so I began adding: “I will order a plate of roast beef once your suppertime starts.” She winked at me, as if I was some alien monkey.

After a few visits with my books and laptop, everyone started calling me Lucy. “So how are your parents in Hong Kong?” they would ask. “Do they want to visit England again?” I was so confused. I wasn’t from Hong Kong, and nor were my parents, even though I secretly wished they were. Then I heard that there had been a girl from Hong Kong who lived there two or three years earlier and also studied at the film school. Apparently she had the same long, black hair as mine. They were so sure that I was Lucy from Hong Kong that I didn’t want to correct them. And I began living the part in order to fit in, making up stories of my former life back in Hong Kong, absorbing bits of information they revealed to me.

“I haven’t seen you in a long time, Lucy,” one of the barmaids said. “I thought you went back to Hong Kong! How’s your family, love?”

“Oh … they are very well, thanks,” I answered vaguely.

“I remember your dad visited you a while back, and he was very fond of our lager. Is he still working for HSBC? Or did he retire?”

“Yes, he just retired.” I guessed that was a plausible answer to her question. She smiled warmly and offered me another free cup of hot water.

My film-school experience wasn’t as friendly as the English pub. My previous training in China was, I quickly discovered, the enemy of the style here. The film-makers I had loved intensely when I was in Beijing such as Dziga Vertov, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Chantal Akerman, Chris Marker and Jean Rouch were considered old-fashioned artists – they belonged only to European cinema. I realised that “auteur cinema” had little place in Britain.

And if I ever pressed my point too much in class, the students would despise me, accusing me of being “pretentious” and “intellectual”. Of course, I felt their judgment was unfair. For me, “being pretentious” was the complete opposite of “being intellectual”. A real intellectual hates empty pretension. But I didn’t want to get into such an argument with the students and teachers, because my English was too limited to say what I wanted. Instead, I spent most of my time alone in the Old Swan, studying English grammar and reading an English dictionary straight from the letter A.

During those desolate days, I thought a lot about my childhood. I had been illiterate until the age of eight, and now, at almost 30, I was once again illiterate. I had to learn how to speak and write in another language, otherwise I wouldn’t be able to construct a life in the west. Identity seemed to be purely a construction – something I had only just realised. But this time the reconstruction felt much tougher than the first time. The pride I had brought with me from China didn’t save me here – instead, it killed me. A feeling of being a “second-class citizen” dominated my every day in Beaconsfield, and made me hang my head in despair.

Originally I thought I would live in Beaconsfield so that I could save time commuting between London and the film school. But after three months of wealth and deathly silence I felt like a weightless ghost, and I couldn’t stand it any more. So I moved out of my shared flat and headed to London. It was simpler than I thought – a 40-minute train ride. And it was worth the cost. I felt life return to me again. Here I was, walking among all the other non-English speaking foreigners. Bengalis, Arabs, Brazilians, Spanish, Germans, French, Italians, Vietnamese and even Icelanders! At least I wasn’t the only Asian face in the street.

In London, I lived first in a stingy, sad little house along a railway line by Tottenham Hale station. Later I moved to a flat on a council estate on Hackney Road that felt like a prison. During those long, rainy nights, with no friends and nowhere to go, my loneliness crept up from my stomach and swallowed me entirely. I couldn’t read much and had difficulty sleeping. My English wasn’t good enough to go through a page of text before I was so completely frustrated by my constant checking of the dictionary. There was no one to talk to.

I often got up in the night, stood by my window and looked out on to the empty, illuminated street. You might hear a police car rushing past, blasting its siren at a deafening volume. Under some dim street light, an old homeless person would be slumped on a bench pulling a newspaper over himself for shelter; then a glass bottle would be smashed against a wall, followed by a chorus of swearing. What harsh, cold, rain-drenched and siren-whining nights they were! London seemed such a dark place, a place of deprivation. How did its people live here for years on end? I hadn’t spent much time in the happier parts of this great capital, the “posh” areas. I was sure the Queen, if ever she woke in the night, didn’t look out on to such gloomy streets. Only the ivy that grew along the rusty fences didn’t notice the brutality of this side of London.

The year I came to England, I was nearing 30. I spent several months in panicked activity as the thought of my age came bearing down on me – to be a 30-year-old woman in China was to be unbearably old. I still remember that celebration in London with some of my classmates from the film school. It was actually the first birthday party I had organised in my entire life. Like most Chinese families at the time, mine never celebrated birthdays. But there I was, cooking Chinese dumplings for my western friends. Everyone declared that 30 was a good age, the age at which you started to know yourself a little, when you were no longer confused and started achieving goals. But I spent that year very confused. I had lost my main tool: language. Here, I was nothing but a witless, dumb, low-class foreigner.

At the end of the Chevening scholarship I was supposed to go back to China. But I didn’t want to. So I struggled to get all the required paperwork together and managed to extend my visa. Now the crucial question was: how do I make a living in the west? I had to survive somehow. But survival wasn’t enough. I wanted dignity. I could only see myself making a living through writing, as I had done in China.

I didn’t want to risk feeling even lonelier than I had in China. It was not just the physical loneliness, but cultural and intellectual isolation. By the time my 30th birthday party drew to a close, I was clear about my direction: I would have to start writing in another tongue. I would use my broken English, even though it would be extremely difficult.

When the birthday party was over, I mopped the floor and did the washing-up. An idea for a novel was already forming in my mind. I would make an advantage out of my disadvantage. I would write a book about a Chinese woman in England struggling with the culture and language. She would compose her own personal English dictionary. The novel would be a sort of phrasebook, recording the things she did and the people she met.

I had to overcome the huge obstacle of my poor English. I decided I didn’t want to go to language classes because I knew my impatience would kill my will, my threshold for boredom being just too low. Instead, I decided to teach myself. Perhaps this was a huge mistake? As I studied day and night I grew more and more frustrated with English as a language, but also as a culture.

The fundamental problem with English for me was that there is no direct connection between words and meanings. In Chinese, most characters are drawn and composed from images. Calligraphy is one of the foundations of the written language. When you write the Chinese for sun, it is 太阳 or 日, which means “an extreme manifestation of Yang energy”. Yang signifies things with strong, bright and hot energy. So “extreme yang” can only mean the sun. But in English, sun is written with three letters, s, u and n, and none of them suggests any greater or deeper meaning. Nor does the word look anything like the sun! Visual imagination and philosophical understandings were useless when it came to European languages.

Technically, the foremost difficulty for an Asian writer who wants to write in English is tense. Verb conjugations in English are, quite simply, a real drag. We Chinese never modify verbs for time or person, nor do we have anything like a subjunctive mood. All tenses are in the present, because once you say something, you mean it in your current time and space. There is no past or future when making a statement. We only add specific time indicators to our verbs if we need them. Take the verb “to go”. In Chinese it is 走, zou, and you can use zou in any context without needing to change it. But in English the verb has all the following forms: goes, went, gone, going. Mastering conjugations was a serious struggle for me, almost a dialectical critique of the metaphysics of grammar.

I particularly detested the past-perfect progressive tense, which I called the Annoying PPP: a continuous action completed at some point in the past. I felt giddy every time I heard the Annoying PPP; I just couldn’t understand how anyone was able to grasp something so complex. For example, my grammar book said: “Peter had been painting his house for weeks, but he finally gave up.” My immediate reaction, even before I got to the grammatical explanation, was: my God, how could someone paint his house for weeks and still give up? I just couldn’t see how time itself could regulate people’s actions as if they were little clocks! As for the grammar, the word order “had been” and the added flourishes like “ing” made my stomach churn. They were bizarre decorations that did nothing but obscure a simple, strong building. My instinct was to say something like: “Peter tries to paint his house, but sadness overwhelms him, causing him to lay down his brushes and give up his dream.”

Another curious realisation came when I discovered that I used the first-person plural too much in my everyday speech. In the west, if I said “We like to eat rice”, it would confuse people. They couldn’t understand who this “we” was referring to. Instead, I should have said “We Chinese like to eat rice”. After a few weeks, I swapped to the first-person singular, as in “I like to eat rice”. But it made me uncomfortable. After all, how could someone who had grown up in a collective society get used to using the first-person singular all the time? The habitual use of “I” requires thinking of yourself as a separate entity in a society of separate entities. But in China no one is a separate entity: either you were born to a non-political peasant household or to a Communist party household. But here, in this foreign country, I had to build a world as a first-person singular – urgently.

Still, the desire and will to work on a first book in English propelled me through the difficulties. Every day, I wrote a detailed diary, filled with the new vocabulary I had learned. The diary became the raw material for my novel, the one I had imagined while mopping the floor after my 30th birthday party: A Concise Chinese–English Dictionary for Lovers.

After I finished the novel, I didn’t know what to do with it. I knew it would have little chance at ever being published, since I had written it using such broken English in a country awash with BBC voices and the perfect sentences of the Queen. And Britain was not like China, where writers could post their manuscripts directly to publishing houses. While pacing up and down in Waterstones one day and wondering how the hell all these books had been published, I happened upon Jung Chang’s Wild Swans. I leafed through it. In the acknowledgements, the author thanked her agent.

In China, writers don’t have agents because, in the world of Chinese socialism, agents have traditionally been viewed as members of the exploiting class. Although I had grown up with this propaganda, I sent my book to Jung Chang’s agent that very day. He was a man called Toby Eady, at an address I had gleaned from an internet search. Who was this man, I wondered. What were the chances that he would pay any attention to a manuscript by an unknown Chinese author?

A month later, one February morning, I received a call from Eady’s office requesting a meeting. After one abortive attempt, we finally managed to meet, and a few months after that, I received an unexpected phone call informing me that Random House wanted to meet me to discuss the book. Leaving my flat at least four hours ahead of the appointed time, I made my way to Pimlico, arriving at the office too early. Sitting on a grey slab outside the publisher’s rain-stained brown mansion building, I ate a prawn sandwich.

Eventually, I walked into the reception area. Disorientated by the number of floors and having to weave my way around mazes of paper-piled desks, I met some editors. They were very friendly and seemed to know a lot about me. One of them made me a cup of Earl Grey. But I still didn’t understand what the meeting was about. By the time I left the office, I didn’t even understand that they had already made a good offer for my novel. At that time, even the word “offer” was alien to me. I didn’t associate “an offer” with money or buying book rights, I thought it meant “Can I offer you a cup of tea, or a piece of cake?” It took me a whole week to understand that the offer was much bigger than a cup of tea.

Some years later, after I had published a number of books in Britain, I managed to finish a novel that I had been labouring on for years. Publication was due in a few months’ time, but I began to worry that it would bring me trouble when I next tried to go back to China, since the story concerned the Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989 and the nature of totalitarianism. What if I was denied entry because of this book? I decided to make preparations before it came out. So, since I had been living in the UK for nearly 10 years, I applied for a British passport.

I spent some months gathering the necessary documents for my naturalisation. After a drawn-out struggle with immigration forms and lawyers, I managed to obtain my passport. Now, I thought to myself, if there was any trouble with my books and films, I would feel a certain security in being a national of a western country. Now I could go back to visit my sick father and see my family.

A week later, I applied for a Chinese visa with my British passport. After waiting at the visa application office in London for about half an hour, I found myself looking at the visa officer through a glass barrier. The woman wore horn-rimmed glasses and had her hair cut short, military-style. She looked like a resurrected Madame Mao. She took my British passport and scanned me up and down. Her face was stern, the muscles around her mouth stiff, just like all the other Communist officials, seemingly trained to keep their faces this way.

“Do you have a Chinese passport?” She stared at me with a cold, calm intensity, clutching my British passport.

I took out my Chinese passport and handed it to her through the narrow window.

She flipped through its pages. The way she handled it gave me a sudden stomach ache. I sensed something bad was coming.

“You know it’s illegal to possess two passports as a Chinese citizen?” she remarked in her even-toned, slightly jarring voice.

“Illegal?” I repeated. My surprise was totally genuine. It had never occurred to me that having two passports was against Chinese law.

The woman glanced at me from the corner of her eye. I couldn’t help but feel the judgment she had formed of me: a criminal! No, worse than that, I was a Chinese criminal who had muddied her own Chinese citizenship with that of a small, foreign state. And to top it all, I was ignorant of the laws of my own country.

She then flipped through my visa application, which was attached to my British passport, and announced: “Since this is the first time you are using your western passport, we will only issue you a two-week visa for China.”

“What?” I was speechless. I had applied for a six-month family visit visa. Before I could even argue, I saw her take out a large pair of scissors and decisively cut the corner off my Chinese passport. She then threw it back out at me. It landed before me on the counter, disfigured and invalid.

I stared, without comprehension, at this once-trusted document. The enormity of what had just happened slowly began to register. Although I was totally ignorant of most Chinese laws, I knew this for certain: when an embassy official cuts your passport, you are no longer a Chinese citizen. I stared back at Madame Mao with growing anger.

“How could you do that?” I stammered, like an idiot who knew nothing of how the world worked.

“This is the law. You have chosen the British passport. You can’t keep the Chinese one.” Case closed. She folded my visa application into my British passport and handed them to another officer, who took it, and all the other waiting passports, to a back room for further processing. She returned her tense face toward me, but she was no longer looking at me. I was already invisible.

There I was, standing in front of the Chinese visa office on Old Jewry, near Bank station. I was still struggling to believe what had just happened. Was that it? I had just lost my Chinese nationality? “But I am Chinese, not British,” I thought. “I don’t feel in any way British, despite my new passport.” Little Madame Mao hadn’t even asked me which passport I wanted to keep, the British or the Chinese. I suppose from her point of view I had already chosen by applying for another nationality, and in doing so, I had forfeited my birthright. For a few minutes I truly hated her, she became an emblem for everything I detested about my homeland, now no longer my country.

My tourist visa was ready a few days later. But for some reason, I never used it. Perhaps because I wasn’t sure what I was supposed to do with a two-week stay. From the day I lost my Chinese passport, I came to the simple revelation that nationality did not declare who I was. I was a woman raised in China and in living in exile in Britain. I was a woman who wrote books and made films. I could have applied for a German passport if I had lived in Germany. But a passport and the nationality written on its cover would never define me.

As the old Chinese saying goes; “Uproot a tree and it will die; uproot a man and he will survive.” I have always agreed with this proverb, especially in the years before I left China. But after the incident at the Chinese visa office, I thought to myself: mere survival is a life without imagination, but a drifter’s life with imagination is also a life without substance. As a new immigrant, everything felt intangible: I couldn’t integrate fully with the locals, nor penetrate the heart of the western culture that surrounded me. But the only way to overcome these problems was to root myself here, to transplant myself into this land and to grow steadily. So I began to plan a life exactly like every other first-generation immigrant, starting with making myself a proper home.

This is an adapted extract from Once Upon a Time in the East: A Story of Growing Up by Xiaolu Guo, which will be published by Chatto & Windus on 26 January. To order a copy for £14.44 go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846.