Why BIPOC Chefs Are Rolling Their Eyes When You Demand Substitutions

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

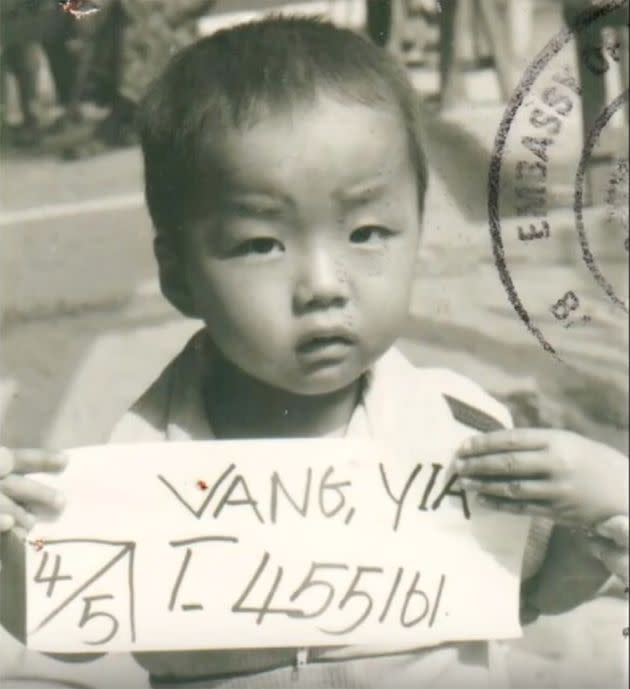

Don’t bother looking for “Hmong-land” on a map, because this nomadic ethnic minority group doesn’t have a home country. Many of them were living in the mountains of Laos when the Vietnam War forced them into the conflict. The CIA recruited soldiers by promising citizenship to those who fought for the U.S., and while many of those promises were eventually broken by our government, some Hmong managed to flee to refugee camps and make their way to the United States. There are now more than 300,000 Hmong Americans in this country, mostly living in Minnesota, Wisconsin and California. From there, this particular story moves from the historical to the personal. Two of those refugees were Nhia and Pang Vang, who settled in the upper Midwest to raise a family of seven children. One of their sons, Yia, has gone on to found Minneapolis’ Union Hmong Kitchen and to be nominated for multiple James Beard awards.

In this Voices in Food story, he tells Julie Kendrick about being ashamed of his mom’s cooking when he was a kid, yearning for Lunchables and SunnyD, and finally coming full circle to tell the story of his parents and his people through their traditional recipes.

What to expect from Hmong food

My people are nomads and storytellers. We’ve lived all over Asia and now the rest of the world, and we’ve taken the best parts of many other culinary cultures and added our own spin to it. Our cuisine definitely draws on the flavors of the Southeast Asian countries that we’ve traveled through. I cook the food I grew up eating — shared mains, bright veggie sides and bold sauces, like Tiger Bite Sauce and Mama Vang’s Hot Sauce. My mom makes that one herself, and she won’t share the recipe with me. She mixes up a 65-gallon batch every fall, and it’s on the menu until we run out.

Here’s what you won’t find: bread on my menu. First, there’s no bread, because we eat rice. There’s no dairy, because it’s hard to keep a herd of cows in the hills of Laos, you know? And there are always plenty of peppers, both for the flavor and because we used them as preservatives when we were on the move. But, most importantly, in every bite you eat, you’ll be aware of the story of our people, because stories are what really matter to us. Our cultural DNA is woven into the food we eat, and it tells you who we are, as long as you’re paying attention.

Why I’ll never make a vegan version of my dad’s Hmong sausage recipe

Last year, I wrote a Facebook post that went viral and was eventually reprinted as an opinion piece in Minneapolis’ Star Tribune. In it, I talked about the mixed message often given to [Black, Indigenous and other people of color] in the restaurant industry. I wrote: “What has been said publicly is ‘be who you are and don’t change for anyone,’ but when you ask us to make changes to dishes that have deep, deep meaning to us, what you’re really saying is ‘please can you change who you are to be authentic enough for my pleasure and palate, because I’m uncomfortable meeting you where you are when it comes to your food.’”

I can remember falling asleep every night and wishing I could be named 'William' ... everyone would be able to spell it and pronounce it. My mom used to try to pack sticky rice, grilled meat and hot sauce for my lunches, but all I wanted was Lunchables.

Now that I’ve had some time to think about it, I have a simpler answer, too: I won’t change the way I make Hmong sausage because it’s not the way my dad makes it, and it wouldn’t taste the same. I understand that people want what they want, and that they’re often unaware of the incredible privilege we have around food in this country. I’ve had enough of the narrative that runs like, “We support you and your brown skin, but now can I get a vegan version of that, hold the hot sauce?”

How to eat a cuisine that’s unfamiliar to you

We’ve all lost so much of our respective cultures by catering to the white palate, because we have to make a living. But if I go into a BIPOC restaurant, I don’t want them to change anything and I’m not going to present them with a long list of dietary preferences. I try to stay quiet and listen to the cooks, listen to the other people eating there. And I don’t try to compare it to something else. I can’t tell you how many times people hear that we lived in Laos and then they say, “Great, I love pad thai!” Pad thai is great, but it has nothing to do with me, and when you tell me that, it means that before you’ve even eaten this food, you’ve made a judgment. People say they’re open-minded, but sometimes their hearts are closed, you know? Food is a universal language, but are you really, truly listening?

Why I used to dream of being ‘William, the kid who ate Lunchables’

My favorite meal my mom made was braised squirrel, but I definitely did not tell that to my all-white classmates when I was growing up in Wisconsin. I never talked about the food she cooked, because I was so embarrassed by it. Instead, I can remember falling asleep every night and wishing I could be named “William,” which seemed like the perfect name to me ― it sounded really, really white, and everyone would be able to spell it and pronounce it. My mom used to try to pack sticky rice, grilled meat and hot sauce for my lunches, but all I wanted was Lunchables. That and a container of SunnyD. Man, I used to think that was the best possible food on earth.

My life since those days has really been a redemption road. I used to be ashamed that my parents didn’t speak English and had weird names. Now I’ve come full circle, and I get to express my love and respect for all the sacrifices they made coming here. I can’t wait to wake up every morning and tell the world about who they are, and to use food as a vehicle to share the life story of two of the greatest parents a kid could ever have. I feel like I’m just a quill — a useless feather that can fly away on the first gust of wind. But my parents are the ink. I’ve taken what I’ve learned from them and created a story with it.

What it’s like to be nominated for a James Beard Award

I’m a finalist for Best Chef: Midwest this year, and Union Hmong Kitchen is a semifinalist for Best New Restaurant. (Winners will be announced June 13.) I try to see the nominations as a good opportunity to talk about what we’re doing. I love seeing people’s eyes light up when they try this food for the first time, even if they only showed up to Union Hmong Kitchen because of the publicity. But my “why” is bigger than any award, and it’s not the end goal. It’s sort of like ketchup on a burger — a tasty condiment, but not the main meat.

How I chose a name for my new restaurant

My soon-to-open restaurant is Vinai, which is named for Ban Vinai, the Thai refugee camp where I was born. It’s the place where thousands of Hmong refugees passed through on their way to America, and it’s the place my parents met. Everything about Vinai is a love letter to my mom and dad, starting with the name, and extending into the way I hope I can honor the past, present and future of Hmong cooking.