Column: Whistleblowers need help. This tech entrepreneur wants to provide it

Public esteem for whistleblowers reached its high water mark in 2002. That’s when three whistleblowers were named Time’s Persons of the Year.

The three women on Time’s cover were hailed as heroes for exposing corporate fraud and shining a light on the critical gaps in America’s national security apparatus — their employers were the corrupt companies Enron and WorldCom and the pre-9/11 FBI.

“They were people who did right just by doing their jobs,” Time wrote, calling the trio “fail-safe systems that did not fail.”

Since that time, corporate managements and government agencies have become more secretive, making whistleblowing even more crucial for exposing wrongdoing. But the people who sacrifice their jobs and careers to bear witness are commonly viewed as turncoats or even traitors, ending up in jail or exile.

There’s attention paid when a journalist is in prison, but when a source is in prison... nobody cares.

— Delphine Halgand-Mishra, the Signals Network

Plainly, whistleblowers need help. Gilles Raymond is stepping forward.

Raymond is the founder of the Signals Network, which is just beginning operations in San Francisco as a support organization for whistleblowers. Launched with $300,000 in seed money from Raymond’s $57-million sale of a news aggregator start-up, News Republic, to the Chinese company Cheetah Mobile in 2016, the Signals Network aims to provide whistleblowers with legal assistance and psychological support, two benefits that Raymond and his staff concluded are sorely needed.

The network, which has been operational for only a couple weeks, will help whistleblowers find legal help and PR representation, work to build secure communications systems, and provide temporary housing to shield a whistleblower from harassment and threats.

Raymond told me the Signals will leave it to the news organizations to develop their sources, evaluate their information, and arrangement publication. His group won’t provide direct financial support to the sources. “We’re very sensitive about any type of direct incentive,” he says. “We don’t want to make them bounty hunters.”

The Signals Network, based in San Francisco, has reached cooperative agreements with five international news organizations, including Germany’s Die Zeit, Britain’s Daily Telegraph, and the Intercept, a U.S.-based investigative news source bankrolled by Pierre Omidyar, the founder of EBay.

Raymond’s fleet of advisors include Peter Bale, a veteran of Reuters and CNN; Dan Gillmor, a former columnist for the San Jose Mercury News and faculty member at Arizona State’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism; Ben Wizner, director of the ACLU’s Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project; and John Kiriakou, a former CIA analyst who helped expose the use of waterboarding by the agency and served 23 months of a 30-month sentence for passing classified information to a journalist, the first such conviction of a CIA officer. Kiriakou had pleaded guilty. The executive director is Delphine Halgand-Mishra, a former North America director for the advocacy organization Reporters Without Borders.

Halgand-Mishra says that after years working with the families of journalists who had been detained for their professional work, including Jason Rezaian, the Washington Post’s Tehran correspondent imprisoned in Iran, and Austin Tice, a freelance journalist kidnapped in Syria and not yet freed, she realized that there can be an imbalance in the attention paid to journalists compared with sources.

“When Gilles started to discuss with me his interest in developing more support for whistleblowers, it immediately resonated,” she says. “I saw that there’s attention paid when a journalist is in prison, but when a source is in prison, there’s nothing, nobody cares.”

One reason may be that it’s easier to question the motivations of a whistleblower, who typically stumbles across damaging information unexpectedly in the course of a day’s work, than of a journalist, whose job is defined as makinginformation public.

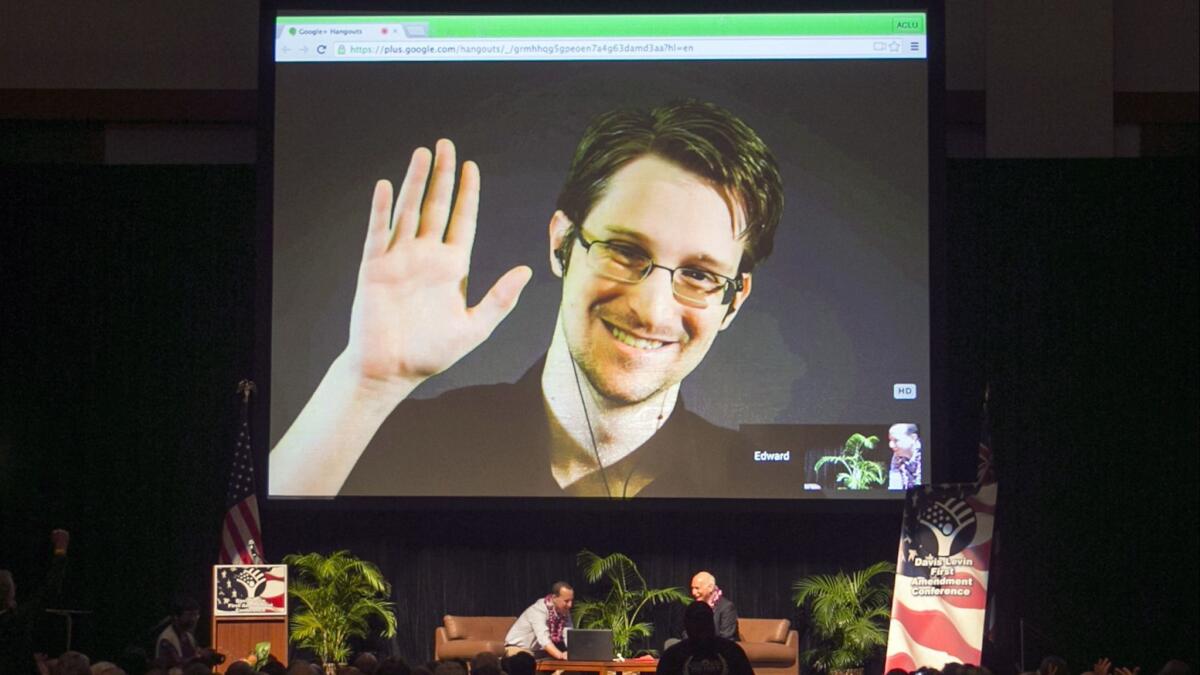

That’s the case with Edward Snowden, who exposed wrongdoing by the National Security Agency and remains in exile in Russia; Reality Winner, an NSA contractor who leaked a top-secret report on Russian hacking of U.S. elections to the Intercept; and Chelsea Manning, an Army soldier who was court-martialed in 2013 for disclosing hundreds of thousands of sensitive government documents to WikiLeaks. Winner pleaded guilty on June 26 and faces a sentence of more than five years in jail; Manning’s 35-year sentence was commuted by President Obama in 2017 to time served.

But the debate over whether they deserved to be praised or condemned for their action started almost at the moment of their own exposures. In 2013, New Yorker writers John Cassidy and Jeffrey Toobin conducted the debate side by side in the pages of their magazine, with Cassidy describing Snowden as a “hero” and Toobin damning him as “a grandiose narcissist who deserves to be in prison.” (Among those voting for “traitor”: California Sen. Dianne Feinstein called Snowden’s disclosures “an act of treason.”)

Whistleblowers themselves face institutional or family pressures to remain silent, or learn the consequences of coming forward only after the fact. “The price of not ignoring what you’re looking at is very damaging,” says Sherron Watkins, one of the three women featured by Time in 2002.

Watkins had warned Enron Chairman Ken Lay that the company’s accounting was improper months before its collapse and bankruptcy.

“Enron imploded too quickly for my career to be ruined there, but I can’t work in corporate America,” she says. “Some people will say I didn’t do enough, others that I come with too much notoriety.” She says one crucial piece of advice for would-be sources is how to remain anonymous: “That would be my biggest question.”

In the 16 years since that Time magazine cover, secrecy has become not only embedded more deeply in business and government practice, but safeguarded by law and administrative fiat.

At the federal government level, whistleblowers are expected to take their complaints about retaliation and claims for back pay to the Merit Systems Protection Board. But the three-member board can’t issue a decision without a quorum, and two of its seats are vacant and the third occupied by a holdover Obama appointee whose term ended in March. President Trump’s two nominees aren’t expected to get on the Senate’s confirmation calendar for months.

That may not be a bad thing. The MSPB had become known for generally upholding agency claims against whistleblowers. A 2009 study by the nonprofit Government Accountability Project found that employees had won only three of more than 50 cases before the board since 2000. The federal Whistleblower Protection Act has proved to be toothless, in part because of rulings by the board.

In the immediate aftermath of the financial crisis of 2008, Congress recognized that corporate officers aware of wrongdoing “often face the difficult choice between telling the truth and… committing ‘career suicide,’ ” the words of a Senate report on the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. Dodd-Frank gave whistleblowers who had suffered retaliation the possibility of recovering double back pay and reinstatement. The source would be in line for up to 30% of any fines the government obtained.

But Dodd-Frank offers its protections only to whistleblowers who bring their information to the SEC. The Supreme Court, in a unanimous 2018 decision written by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, ruled that the protections excluded those who bring their complaints internally.

Whistleblower advocates say the decision overlooked a half-century of case law treating internal complaints as tantamount to SEC enforcement. “That was the single greatest loss for whistleblowers in 50 years,” says Michael D. Kohn, a Washington-based attorney for sources. Some 90% of whistleblowing is done through internal procedures, Kohn told me, and the vast majority never reach the SEC.

In many cases, the laws protecting whistleblowers from retaliation are “a patchwork with grave gaps” that are “difficult for lawyers to comprehend, let alone laypersons,” Kohn says.

The work of whistleblowing is becoming only more complex and difficult. Daniel Ellsberg worked largely alone when he leaked the 7,000-page Pentagon Papers in 1971; but teams from more than 100 news organizations worked to mine the Panama Papers, a trove of 11.5 million documents related to offshore financial transactions leaked anonymously in 2015.

“We’re at a time in world affairs when whistleblowers have never been needed more and on a fairly regular basis show why they’re important,” Gillmor says. “The need to help them seems obvious.”

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com.

Return to Michael Hiltzik’s blog.