Theresa May will ultimately be remembered as the prime minister who was defeated by Brexit. Her task was to reconcile a nation split by the surprise referendum result. But if it was possible to achieve a graceful exit from the European Union, or indeed any exit, May utterly failed to negotiate it.

The crown had fallen unexpectedly into her lap. David Cameron and George Osborne had already catastrophically misjudged the public mood over Europe (as May was to three years later). Boris Johnson had misjudged his relationship with Michael Gove.

She gave the appearance of the only remaining grown-up in the race, and when her last remaining rival, Andrea Leadsom, pulled out, May entered No 10 in July 2016, just three weeks after the referendum. However, the meticulous but cautious home secretary had had no real time to work up an agenda for government.

There was no obvious blueprint for Brexit, which May had, ironically, come out against during the referendum campaign. So as the new prime minister arrived in Downing Street, she made a pledge about something else.

May promised to fight “burning injustice” – and on her first day in office said she aimed to reverse the disadvantages of race, class, gender and even youth. She fired Osborne, brought in chief Brexiter Johnson as foreign secretary and promised in her first party conference speech “change is going to come”.

They were ideas that came from one of the two key advisers in the first phase of her premiership, Nick Timothy, who sought to position May as a supporter of ordinary Britons. “If you believe you’re a citizen of the world, you’re a citizen of nowhere,” she declared in an anti-elitist sideswipe from the same conference speech.

In reality, May delivered only limited social reforms. Ultimately, Brexit dominated her premiership and, in the end, little else could be achieved.

‘There was no warmth’

She repeatedly described politics as a duty, sticking to her Brexit plans with a grim determination or stubbornness that surprised and ultimately alienated even her closest supporters. Famously introverted, she relied on a tight circle of advisers – officials and aides normally – and rarely on elected colleagues.

But she struggled to engender loyalty among those who once served her closely. Key supporters were easily discarded and many later turned on her – Timothy, who took the blame for the 2017 election disaster, or Gavin Williamson who propped her up after it only to be sacked from the cabinet two years later over the Huawei leaks.

Chris Wilkins, a speechwriter who had worked with her as home secretary and prime minister, said: “There was a long period when I would have run through walls for her. But once she you had stopped working for her, there was no warmth, no ongoing relationship.”

The new prime minister began uncompromisingly enough though. She made a Brexit speech at the same 2016 party conference promising that Britain would become “a fully independent, sovereign country”.

It was a hard Brexit vision that implied leaving the customs union and single market, which it was not obvious a majority of Britons had voted for. But it defined the pure Brexit that for her gradually growing numbers of rightwing critics became an article of faith.

That was made explicit in another speech in January 2017 at Lancaster House in London. She confirmed the UK would leave the single market and abandon full membership of the customs union, and if all else failed she boldly declared “no deal for Britain is better than a bad deal for Britain”.

It was a speech that was well received by Conservatives at the time. “Steel of the new Iron Lady,” the Daily Mail wrote, offering a memorable cartoon image of May in a suit standing on the white cliffs of Dover.

‘Nothing has changed’

Comfortably ahead of Labour in the polls, May decided to hold a snap general election during after an Easter walking holiday in Wales with her husband, Philip. A few days later, broadcasters were put on notice, a lectern appeared in Downing Street one morning, and speculation reached fever pitch.

“The country is coming together but Westminster is not,” she said, announcing the election minutes later. Projections at the time suggested the Tories could secure a majority of 140, with nearly 400 seats, while Labour would plunge below 200, which would have been the opposition party’s worst result since the 1920s.

But the election campaign was a disaster. The prime minister was awkward and uncomfortable throughout, sometimes becoming incomprehensible in difficult moments.

No 10 had tried to build a campaign around her, beginning with the ad nauseam repetition of the phrase “strong and stable”. But May refused to take part in television debates, leading to accusations she was afraid.

Nor could the prime minister create a rapport with the electorate, earning derision when she declared that the naughtiest thing she ever did as a child was “run through fields of wheat”.

John Crace, the Guardian’s sketch writer, first dubbed her “the Maybot” in November 2016 and the term gained a wide circulation during the campaign, even in the rightwing press and among staff at Downing Street.

The manifesto was also a disaster. Its signature policy amounted to an attempt to force people to pay far more for the costs of their own social care, including with the equity they had built up in their homes.

Labour successfully branded it a “dementia tax” and May was forced into a complicated U-turn, which she tried and failed to disguise. “Nothing has changed, nothing has changed,” an arm-waving prime minister declared on the campaign trail in Wrexham.

The Conservatives lost their majority in parliament and May had to secure a deal with the DUP to prop up the government.

May’s two key advisers, Timothy and communications supremo Fiona Hill, went. But otherwise May acted as if little else had changed.

A lock-in at Chequers

The Brexit negotiations continued slowly and largely in secret, relying heavily on top official Oliver Robbins, whom she took from the Brexit secretary, David Davis, and made him report directly to her.

It was characteristic of her reliance on a small group of trusted advisers. But her most important source of support was her husband of 38 years, Philip.

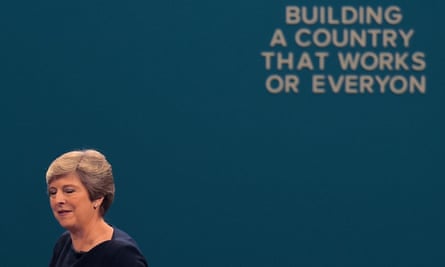

Philip May was the man who rushed on stage to scoop up the prime minister in a hug after she concluded an excruciating conference speech in 2017, which had been overshadowed by a persistent cough, an ambush from a protester wielding a fake P45 and letters from the backdrop falling off.

The prime minister’s husband would turn up at Downing Street meetings at key points, often to the irritation of aides. “You really didn’t want him to turn up to a meeting ahead of a key speech. The problem was he thought he could write, but the reality was he couldn’t; his presence made things a lot harder,” one former aide said.

Senior politicians complained that May was the same in private as in public; sometimes at key moments in cabinet meetings, she would read from a pre-prepared script to get through a difficult moment. Often she said little, giving people the mistaken impression she agreed with them.

In the Brexit negotiations, cabinet members, coalition partners and the public at large were updated only periodically and often did not like what they saw when it emerged, creating a string of crises that eroded May’s authority.

TimelineTheresa May in power

Show

Theresa May becomes the UK's second female prime minister. In her first cabinet, she appoints Boris Johnson as foreign secretary, David Davis as Brexit secretary, and Liam Fox as international trade secretary.

May gives her Lancaster House speech outlining her approach to navigating Brexit. It sets out the red lines that will continue to cause difficulties with her own party two years later.

Formal notice is given to the EU, under article 50 of the Lisbon treaty, that the UK intends to leave the bloc.

Despite having previously ruled it out, May calls a snap general election, accusing opposition parties of trying to jeopardise Brexit preparations. Projections suggest she could secure a majority of 140.

After a disastrous campaign performance, May loses her majority in the Commons. Within days of the election, she is forced to do a deal with the DUP to get a working majority.

May's speech at the Conservative conference lurches from disaster to disaster, as a cough mars her delivery, a protestor manages to hand her a P45, and letters start falling off the backdrop behind her.

After the Chequers summit, David Davis resigns as Brexit secretary over the prime minister's withdrawal agreement with the EU. Boris Johnson follows Davis out the door the next day, claiming the UK was headed 'for the status of a colony'.

The text of the withdrawal agreement is published. It is approved by the EU two weeks later.

May loses a second Brexit secretary as Dominic Raab resigns, saying he cannot support the deal he helped the PM negotiate. The work and pensions secretary Esther McVey resigns the same day.

May's government is found to be in contempt of parliament after refusing to publish the full legal advice it received over Brexit.

Although more than a third of her MPs vote against her, May survives a Tory vote of no confidence. Under party rules she cannot be challenged again for another 12 months.

May suffers the heaviest parliamentary defeat of a British prime minister in the democratic era, losing a meaningful vote on her Brexit withdrawal deal by a majority of 230.

May's deal is again voted down by parliament, this time by a majority of 149.

On the day that parliament votes against eight different alternative Brexit options, Theresa May tells her backbench MPs she will stand down as soon as her deal passed.

On the eve of European parliamentary elections May desperately wanted to avoid, the leader of the house, Andrea Leadsom, quits the cabinet. She is unhappy with 10 new commitments May has added to her withdrawal agreement bill in an attempt to get cross-party consensus.

Theresa May announces she will formally resign as Conservative party leader on 7 June, sparking a leadership content that sees Boris Johnson and Jeremy Hunt vying to be the next prime minister.

The first phase of talks nearly collapsed in December 2017, when the DUP was finally shown the first draft of the Irish backstop while May was in Brussels hoping to unveil the deal after a working lunch with Jean-Claude Juncker.

May took a phone call from the DUP leader, Arlene Foster, who said her party could not sign up to a text they had only just seen. The mystery was why the prime minister had left it to the last minute to try to bounce the DUP into a deal.

In July 2018, ministers were locked in Chequers, the prime minister’s rural retreat, for a day to be shown May’s free trade plan. It was news to the Brexit secretary, Davis, and called for the UK to adopt the EU’s standards on food and goods after leaving the bloc.

Davis quit two days later, saying May had “given away too much and too easily”. Johnson followed hours later, quitting as foreign secretary and complaining that May’s plan would reduce Britain to the “status of a colony”.

‘Stamina is not a strategy’

May finally concluded negotiations in November after trying to wear down the cabinet to make it clear that the backstop would have to be in the withdrawal agreement and that any exit from its provisions would have to be jointly agreed with the EU.

The plan of attrition failed. Two more cabinet ministers resigned: Dominic Raab and Esther McVey. Even May admitted that the five-hour cabinet meeting to sign it off was “long and impassioned”.

It was clear there was no majority in parliament for her deal in December, so May pulled the vote, after admitting that she would have been defeated “by a significant margin”. It was the first in a succession of humiliations.

By now enough letters – 48 – had been handed to Sir Graham Brady, the chairman of the Conservative party’s backbench 1922 Committee, to force an ill-timed vote of confidence in her leadership. “Stamina is not a strategy,” backbench critic Lee Rowley woundingly said in her hustings.

May made her first offer to resign in the Westminster committee room – at some indeterminate point before the general election in 2022. It helped her win a pyrrhic victory: 200 to 117, while her critics were later to rue the fact that party rules meant she could not, in theory, face a challenge for another year.

A third of her parliamentary party and half the backbenchers were against her. Yet, speaking outside Downing Street, May said that night she had a “renewed mission” that she said involved “delivering the Brexit that people voted for” and failed otherwise to change course.

The long-awaited “meaningful vote” took place in January because the prime minister could no longer dodge it and May’s deal was defeated by an extraordinary 230 votes – the worst defeat for a government in modern times with 118 Tories voting against.

Two months of mostly inconclusive talks followed; with all sides feeling that May was trying to run down the clock to the 29 March deadline for Britain to leave the EU and force MPs to agree to the deal she had negotiated, because the alternative – no deal – would be worse. But her bluff was called.

May eventually braved a second vote in mid-March. The prime minister had barely changed her Brexit deal, but won some modest extra commitments from the European Union that the backstop would be temporary.

Perhaps recognising this was truly the pivotal moment, her voice went as she returned from Brussels, a piece of paper in her hand. You “should hear Jean-Claude Juncker’s voice”, May quipped, although she was greeted with a largely unsympathetic silence.

Downing Street aides thought this was the moment she came closest to succeeding. But the deal was defeated by 149 votes on 12 March , with 75 Tories rebelling, scuppered by an intervention from the attorney general, Geoffrey Cox, who said the concessions May had won made no difference.

One last desperate and reckless act

At this point, May’s authority collapsed, although the Tory party proved unwilling to to administer the coup de grace, because nobody else could see a way through the Brexit impasse. Instead May was forced back to Brussels twice to ask for extensions that her own MPs would not vote for in the Commons.

Cabinet discipline had come to an end, as would-be successors and kingmakers jostled for position. Leaks would emerge within minutes of meetings breaking up, prompting repeated complaints from the prime minister about leaks, which in turn immediately leaked.

May entered a bewildering cycle of meetings with her biggest Tory critics led by Johnson and finally promised to quit as prime minister once her phase one Brexit deal was voted through.

The sacrifice won him around – but not enough others. May lost a third Brexit vote on what had been intended to be the Brexit deadline of 29 March by 344 to 286, unable to win around Tory refuseniks or woo any Labour support. By now she had conceded that her premiership would soon end.

An undesired European election had become inevitable too, bringing back the one rightwing politician with the courage to take her on: Nigel Farage. Soon his Brexit party was topping the polls – while the Conservatives were at risk of finishing an embarrassing fifth behind the Greens – before the prime minister embarked on one last desperate and reckless act.

Implausibly declaring “this is a great time to be alive”, May stunned colleagues in the week of the election by promising to introduce “a requirement to vote on whether to hold a second referendum” so vehemently opposed by almost all her own party.

It prompted yet another cabinet resignation, that of Andrea Leadsom, who complained there has been “a breakdown of government processes” as May had presented yet another surprise Brexit manoeuvre to her senior colleagues. With zero chance of a fourth Brexit vote succeeding, there no longer seemed any point in May being prime minister at all.