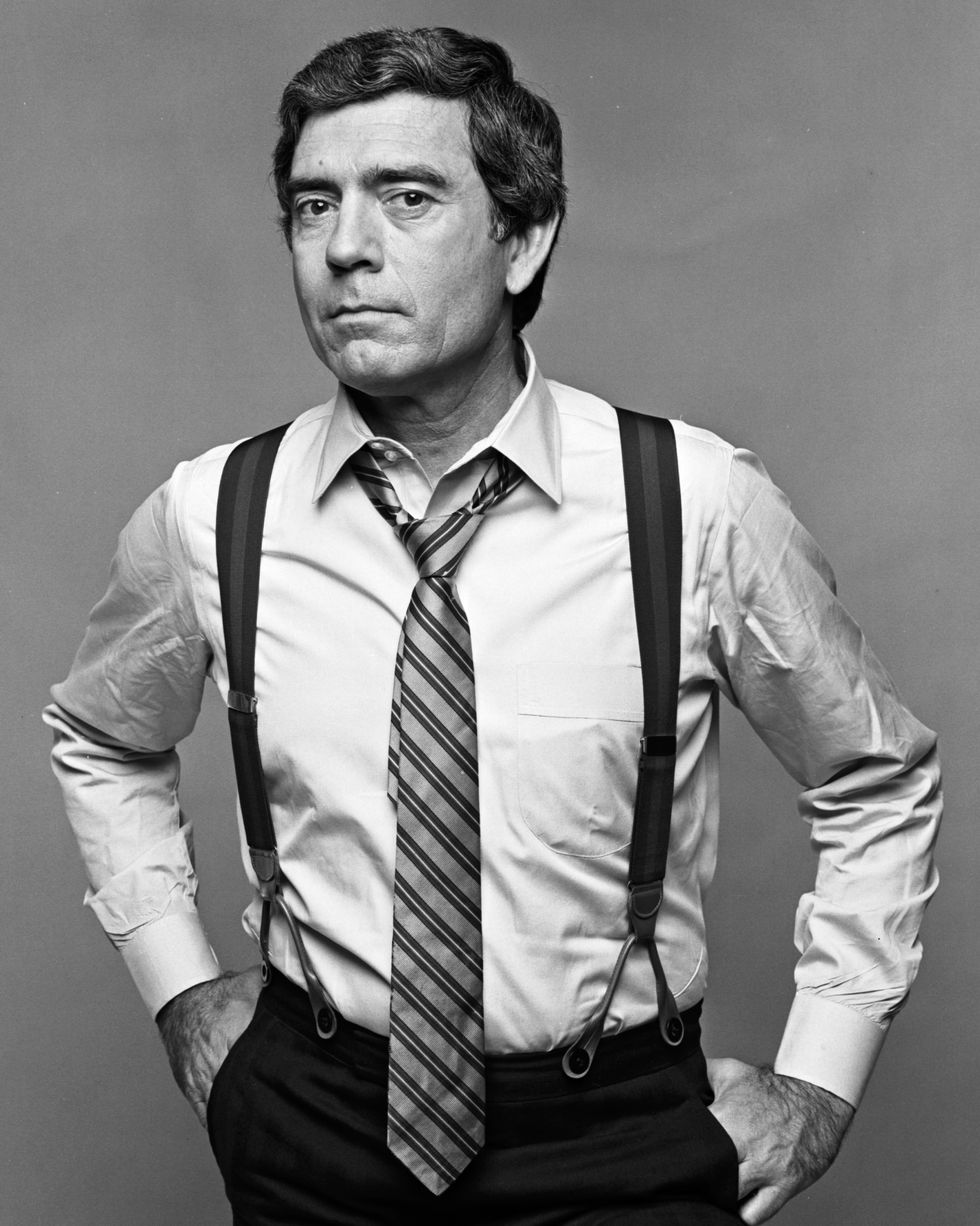

Standing amid the wreckage of late 2020, it’s funny, and a little sad, to look back at the moment when Dan Rather took the piss out of Richard Nixon on national television.

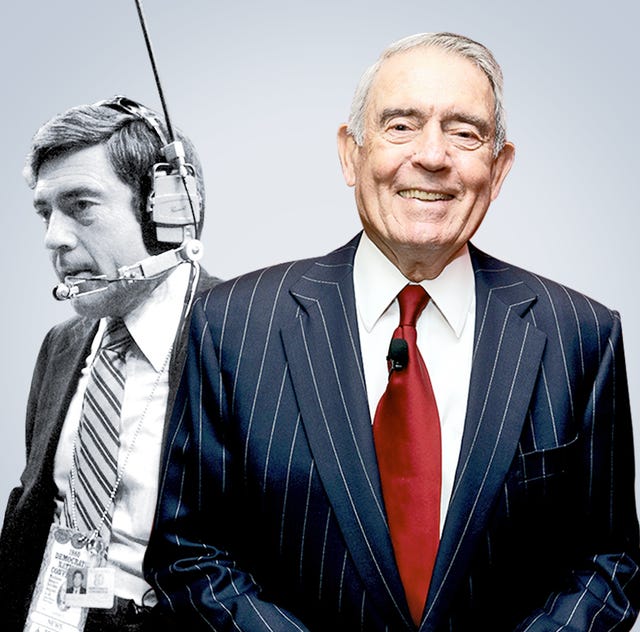

Rather, who will turn 89 on Halloween, has been an unlikely commentator on this mess of a year, employing social media to call out President Trump on his calamitous leadership and to offer hope that things can get better. He has also read some poetry to his considerable following: 1.4 million on Twitter, 2.7 million on Facebook. When he speaks, or writes, it is with not only nine decades of experiences behind him but six decades of reporting on, investigating, and searching for truths in American politics and culture.

He is a man to listen to.

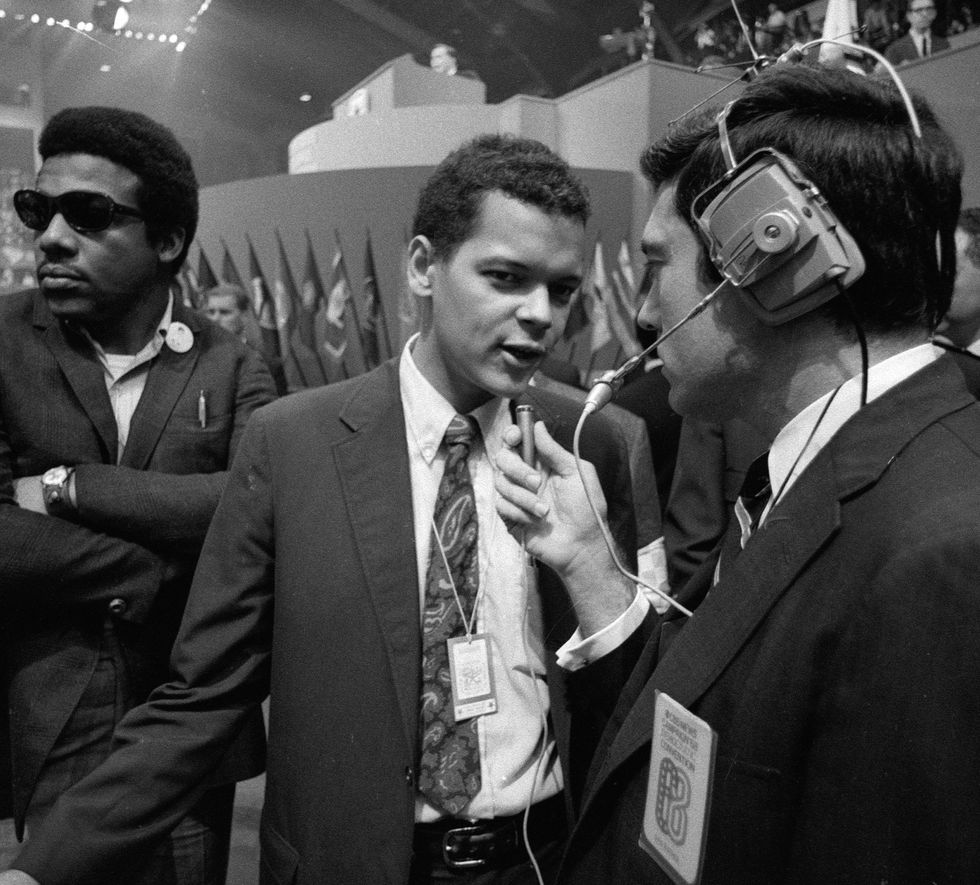

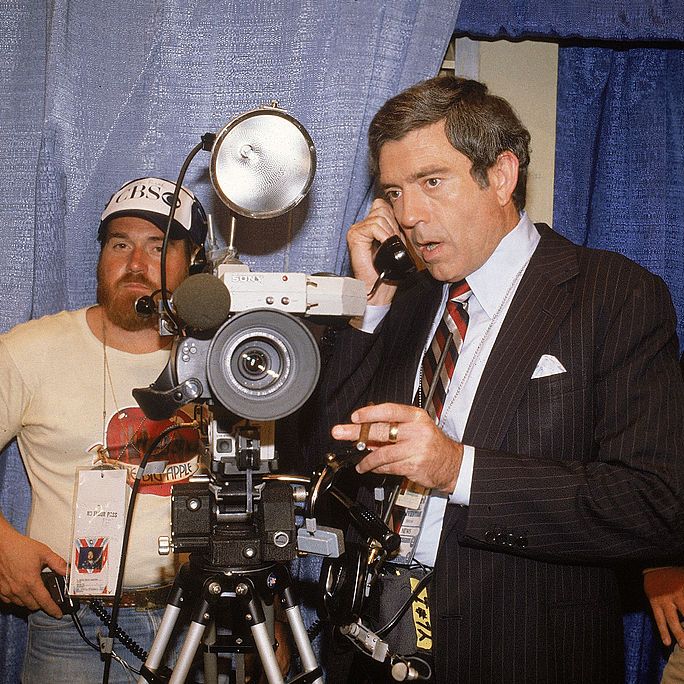

The Nixon moment came during a press conference in Houston, March 1974. The height of Watergate, less than five months before Nixon would resign. He was doing a kind of goodwill tour, getting out in front of people, looking presidential. The press was supposed to be only local friendlies, but Rather, the CBS White House correspondent at the time, was there.

“Thank you, Mr. President, Dan Rather with CBS News,” he said, standing when it was his turn to ask a question.

A few people clapped, but a lot booed. Nixon is the only other president besides Donald Trump known to have publicly called the press “the enemy,” and the audience that night was full of loyal supporters of the president. The boos swelled to jeers.

Nixon listened to the boos and jeers for a few seconds, then quipped to Rather, “Are you running for something?” The president beamed at his own clever joke.

When the laughter died down, Rather replied, “No, sir, Mr. President. Are you?”

At this shocking display of irreverence and jocularity, the crowd went wild with laughter.

Back then, Rather was a rising star of the news, twelve years into a national career after being plucked from KHOU in Houston, when he caught the attention of the national network for his coverage of a hurricane in 1961. (It was the largest on record, and Rather cajoled the National Weather Bureau into letting him report from inside its new radar facility in Galveston; during thirty-six hours of continuous coverage, at one point Rather invented the concept of superimposing a map over the radar screen so viewers could see where the storm was tracking—forever changing televised weather reports.)

He had covered the civil-rights movement and three assassinations (Kennedy, King, Kennedy). He was known for earnestness; a deep, trustworthy voice; and the ability to keep his emotions out of his reporting, a talent he has referred to as “detachment.” He was on his way to the anchor chair of the CBS Evening News, which he would hold for twenty-four years, starting in 1981, before being ousted in 2005 over a report challenging President George W. Bush’s military record. The reasons for his departure were controversial, and were the basis for the 2015 movie Truth, in which Robert Redford plays Rather.

Today he runs his own production company, called News and Guts, focused on investigative reporting. He is free to tweet what he wants (“There will be no vaccine for the climate crisis”) and to write essayistic posts about democracy and humanity. He is older than some dirt roads, and free to say whatever the hell he wants.

The Nixon moment is funny because it was a light, extemporaneous exchange between a president and a journalist he loathed.

It’s a little sad because these days we don’t see that kind of levity between a president and a journalist. I asked Rather recently whether in his six decades as a reporter he has ever experienced the kind of public treatment some journalists receive from President Trump: insults to their intelligence, sarcasm, orders to sit or leave.

“No, no, the answer is no. I haven’t,” he said. “The exchange with President Nixon stood out at the time because it hadn’t been done before. Or at least not in that direct a fashion, not with that much drama surrounding it—the whole background of Nixon leading a widespread criminal conspiracy within his presidency and all. But at the time it was ‘Wooo!’ because it wasn’t being done. And as bad as Nixon was—and you will never hear me say he was anything other than one of the worst presidents in history, if not the worst president in history, before the current president—the difference between Nixon and President Trump is that, first of all, Nixon deep down believed in the institutions of government. No misunderstanding—I’m not complimenting him, but that was the norm. And he would himself criticize individual reporters and journalistic institutions, but most of the time President Nixon would do that behind the scenes, or using surrogates. Now, with President Trump, he criticizes not only individual reporters but basically all of journalism. Every journalist is no good, is evil, is a threat to democracy, is treasonous. Everybody. He does it himself. He does it consistently, relentlessly, and he does it for the purpose of personal gain, which is to say keeping himself in office.”

Rather speaks in short essays. He never liked Teleprompters, and his ability to speak in measured sentences that accumulate, building thought by careful thought, into a cohesive, hard-won, and often surprising synthesis, remains intact.

At the appointed time of our first conversation, Rather—Dan Fucking Rather!—appears on the screen, just as he did when I was a kid and he would appear on the TV screen in the basement at six o’clock. Only now he’s on my screen, talking to me, wearing an olive-drab shirt with epaulets, which he could have been wearing in Kuwait or Johannesburg or the Florida panhandle during some 60 Minutes segment during the Reagan administration.

We perform the Zoom ritual of turning on mics and peering into the webcam and smiling when we think it might be working. “I thank you for your time and your interest,” Rather says once he’s confident I can see and hear him, “and I’ll do my best to make this the best interview you’ve ever done.”

We spent nearly three hours talking in this and a subsequent conversation. What follows are excerpts from those interviews, barely edited but for clarity and length, and with a bit of context where necessary.

It’s rare access to Dan Rather, who calls himself simply a reporter but is in fact the great interpreter of our time.

ESQUIRE: In the 1980s and ’90s, America got its TV news from the Big Three: yourself on CBS, Peter Jennings on ABC, and Tom Brokaw on NBC. All white men, about the same age. Journalism has improved some in this regard, but not enough. What can people in power—who are mostly white people—do now to increase the number of people of color who are reporting and delivering the news?

RATHER: When I fault myself—and I’d say fairly often I do fault myself on this subject—it is, well, okay, Dan, you’ve always been a pretty good listener, you have borne witness to things you’ve seen, and yes you have thought about it before. But you haven’t acted as much or as decisively as you could have.

So: act. But like what, for example? First of all, you want to set an example. I’m not in a position to hire anybody, particularly at this moment. The economy is shrinking and my company, News and Guts—frankly I don’t know whether I can hold it together, though I think I can. But we’re at a moment of opportunity now when it comes to hiring.

One of Rather’s first assignments for CBS News in the early 1960s was to cover the civil-rights movement in the South. He reported from Oxford the day James Meredith was admitted as the first Black student at the University of Mississippi. The campus was chaotic and hostile toward the news media, and Rather was crawling around in the darkness all night to file reports, using the camera’s light sparingly because it attracted gunfire.

During those years, he wrote in his 1977 memoir The Camera Never Blinks, “I was totally unprepared, emotionally and intellectually, for the evils committed in the name of racial segregation. Who would have believed that a police chief would turn loose vicious dogs on children? Who would think that adults could turn over an elementary school bus and beat its side with ax handles?”

RATHER [continued]: For a long time, it just seemed the movement toward any progress on civil rights was so tiny as to be barely perceptible. It was more like a great amount of snow that moves along so slowly you don’t even know it’s moving.

But then there’s an avalanche.

That’s what happened in the ’60s, partly because there was an opportunity in the wake of John Kennedy’s assassination, that we did have significant civil-rights legislation pass. Was it enough? Did all of it turn out perfectly? No. But it was, one could argue, and I would argue, the most forward movement we’ve had on civil rights since Lincoln’s time. So I think here in 2020, there’s an opportunity for the same thing to happen, if you use my metaphor, for an avalanche of real action.

When I first came to CBS News—I started in 1962—there was no correspondent of color. After that, it was slow going, but there were efforts made. But there were very few steps, and they were tentative steps. I do remember when the decision was made to bring the late Ed Bradley onto 60 Minutes as a correspondent, I’m not sure the decision would have been made if I hadn’t been moving to the evening news. It was not my decision to make, but in other words, I was opening up a position. I recommended Ed Bradley, and I was not the only one—it was almost a consensus. But he was the first. And I’m not singling out 60 Minutes, but 60 Minutes had been around since, maybe ’68? So between 1968 and 1981 there was not a single black correspondent.

Everybody, including myself, to varying degrees, bears some responsibility for that.

It’s still true—I’m not on a soapbox about this, but with local stations, as well as with networks, there’s considerably more representation in on-air positions of people of color. But there aren’t nearly as many in the high decision-making positions. Behind the camera.

ESQUIRE: You’ve written nearly 16,000 tweets in your life. Can social media be a form of journalism?

RATHER: I think the answer is yes—if you believe, as I have come to believe, that one of the things that identifies journalism is that you don’t stay silent. Something happens [purses lips, almost smiles], you tell it. And social media is another vehicle, another platform, another opportunity, to tell it. And to ask the more important questions of the day.

To what purpose? I know people get tired of hearing this, but [he shrugs] like every other journalist who’s worthy of the name, the purpose is: to gather facts, and analyze the facts, in order to get as close to the truth as is humanly possible. Recognizing that sometimes you can get reeeally close to it [his eyes go wide], and other times, even with your best efforts, you don’t get very close.

ESQUIRE: These days, saying the wrong thing—something that comes off as offensive or insensitive, even inadvertently—can sink a person. I think of you out in the field, unscripted, back in the day. Is today’s environment a little scary?

RATHER: Oh, it’s a lot scary. I was raised to fear only God and hurricanes, but I have come to really fear this—it’s a daily, almost hourly fear that you might, in haste, write something down that you didn’t mean or that can be taken more than one way. And you say to yourself, Whoa, I didn’t intend that! That’s so far from what I intended. But too late.

So I really do fear that.

ESQUIRE: Do you have any misgivings about continuing to use Facebook, given the questions around the site’s allowing misinformation in the name of free speech?

RATHER: Yes. I do. It’s a dilemma. I don’t want to make an excuse—I’m responsible for what I do. But increasingly I’ve been asking myself the question, Do I stay on Facebook? And I discuss it with the younger people on my staff—of course they’re all younger now.

I confess that part of me says, Listen, time to go. Just on a matter of principle. On the other hand, it’s the old story where we’ve spent a lot of time and a lot of effort to carve out a space for ourselves on Facebook, and for an aging anchorman on the back side of the slope, a Facebook following of 2.6, 2.7 million people, I don’t apologize for saying to myself, “Tough to give that up.” When you write something, you hope somebody will read it. Otherwise why are you doing your work?

So the answer to your question is, at this very moment, just swallow hard and go on. And I’m not sure I’m right about that.

ESQUIRE: You spent a lot of time with Donald Trump in 1999, the first time he ran for president, for a 60 Minutes segment. What stands out in your mind about the experience?

RATHER: Well, one, Donald Trump invited us into the bedroom one night when Melania was already in bed and he was getting ready for bed. And it was “Come right on in!” He was not embarrassed, and she was not embarrassed. I remember being embarrassed and sort of saying, I don’t think so.

Another thing that stands out in my mind was how controlling Donald Trump wanted to be. He was super cooperative, as evidenced by the “come into the bedroom, get a shot in here, that’ll get an audience.” He couldn’t help himself. He was trying to produce the piece. At that time, he had the Trump Shuttle, or some airline bearing his name, and he wanted us to fly with him to Mar-a-Lago. And we thought, Should we do this or just buy our own tickets? And he wouldn’t hear of it. He said, “Oh my God, you’ve gotta be on the plane and shoot on the plane. What kind of piece is this going to be if you’re not on the plane?”

He was a born salesman. His image of himself was that he was a supersalesman. That he could sell ice to Eskimos. That, just give me a chance with a potential customer and I can sell it.

He hated the piece, which said: He says he’s running a presidential campaign, but basically what it is is a campaign to sell golf-club memberships and condominiums. Which he was.

Well, the minute it ran, effectively any relationship we had, no matter how tenuous it may have been, was over. It was one of those telephone calls where you have to hold the phone away from your ear, into which he was giving me a good tongue-lashing and cursing about how he had helped me, he had cooperated for me, he had known me a number of years and he trusted me. Which was the last conversation of any sort that I had with him.

ESQUIRE: That was the last time you spoke with him?

RATHER: Yes. At succeeding banquets for the New York Police Athletic League, of which he and I were both on the board, he was stone-cold freezing.

ESQUIRE: How do Trump’s scandals just disappear? How can something like the president knowing about Russian bounties on U.S. troops not topple an administration?

RATHER: I asked myself this very question yesterday. I went, Wait a minute, these things, all kinds of stories—during the 2016 campaign, then-candidate Trump mimicked the Times reporter who had a physical challenge. Outrageous! Despicable. This is not in the American campaign character and never has been.

But whatever happened to that? It was news for half a day, maybe a day. And it really got my ears up at the time. Everything from those relatively small things, to time and time again whatever the hell he’s doing with Putin, the president does things that are strange to the point of being weird, but that we know are dangerous. But they, as you say, kind of fall off the table in a day or half a day, or if it runs half a week, it’s a miracle.

I think the answer to how and why that happens has to do with a certain talent that President Trump has, and that is the talent for diversion. Getting the subject changed. He’s a master at using television and the Internet, basically tweets, and knowing how to personally, himself, walk out on television and have the subject changed very quickly.

We know that he thinks a lot about this. He spends an inordinate amount of time watching television, we know—basically Fox. And he tees off what he sees on television. So if he sees news coverage going in a certain direction, and he says to himself, This is not a good direction for me, boom, I’m going to walk out and change the subject, or send a tweet, or send twelve or twenty tweets.

And there’s a reluctance to give him credit, I hate to use the phrase “give him credit,” but you have to recognize that he’s very talented. He’s crafty.

ESQUIRE: There are journalists, perhaps more these days, who hesitate to pursue stories about people they disagree with, or whom they consider bad or dangerous—for some this might mean someone like Alex Jones—so as not to give those people “a platform.”

RATHER: I’m on the other side of that argument. I don’t see it as giving them a platform. If it’s a public person, it gets down to the basic question for journalists, Why am I in this? One of the lead reasons I’m in this is that I’d like to get to the truth, or as close to the truth as is humanly possible. So what is the truth of Alex Jones? As Butch Cassidy said to the Sundance Kid, Who are these guys? And in answering that question—Who is he? Who are these people?—then a professional journalist doing his work can shed some light on that. So I don’t have much patience for this argument that, Oh we’re giving him a platform.

And listen: They have a platform. They’re going to create their own narrative. So who is going to check the narrative they’re creating for themselves? That’s one of the roles journalists perform.

ESQUIRE: Does the word courage mean something different today from when you used the word as your sign-off in your final CBS News broadcast in 2005?

RATHER: I like the word—I like the inner rhythm of the word. I like it because it was my father’s favorite word. I like it because I have seen real courage, both of the battlefield variety and of the variety that’s more moral courage.

With journalists, there’s a tendency to say to yourself, Just stay in the middle and move with the herd. That way you don’t get hurt. And today, frankly, there are more ways to get hurt. When I broke into journalism, lo those many years ago at a small weekly newspaper, we had a deadline of sorts every week. A deadline every week! If you worked for the CBS Evening News with Douglas Edwards or Walter Cronkite, your deadline was 5:00, 5:30 in the afternoon. And when that deadline passed, that was pretty much it.

Now, with the advent of cable television, satellite, and particularly the Internet, it’s a deadline every nanosecond.

And you know the danger of that: You don’t get as much time to double-check. Sometimes you don’t have any time to double-check.

There’s that fear: Just do it the easy way, the safe way. Same with asking questions, where the higher you go up on the scale of powerful people, the heavier the undertow is. For heaven’s sakes, don’t put yourself in a position where somebody can hang a sign around you that labels you “unpatriotic” or “anti-Republican” or “anti-Democrat.” Just go through the questions on your list, and whatever the interview subject says, go to the next question. Even if he throws some clear, unadulterated bullshit at you, when you know you want to follow up with a question and call it for what it is, instead it’s quick [snaps]. It’s: Don’t get yourself in trouble. Just move on to the next thing.

I’ve done it, I’d be very surprised if you haven’t done it. [Shrugs.] Almost every journalist has done it, and the reason is fear.

It requires courage to overcome those natural tendencies. And listen, I want to emphasize, I’m not saying this because I have courage. I want to have courage. I ache to have courage. I regret those times when I had the opportunity to have the guts to stand up and have courage and didn’t do it.

Courage is in such short supply.

ESQUIRE: Another word you used recently was steady, in a Facebook post. You wrote, “This moment’s problems are particularly severe, but they are not insurmountable.” But this was before George Floyd. You’ve seen so much, and made a living making sense of it. How are things looking now?

RATHER: Well, this is one of the low points in American history. We have this extremely difficult virus which we have failed to meet and to deal with in a responsible way, and which has contributed to—one can even say led to—an economic collapse the likes of which we’ve not seen since the early days of the Depression. We have a political crisis in the country, made up of the dysfunction of the Trump administration. Plus a broad-based movement in the streets for change, which has as its base anti-racism as a result of the Floyd situation in Minnesota.

Also in this dangerous, explosive, toxic time, there are real and extremely dangerous external threats. The Russians have come up with a way of battling us which is new, different, doesn’t involve battleships and aircrafts and clanking tanks. It’s cyberwarfare.

This is different from anything we’ve seen in this country. There have been other periods, but not a period with all of these various factors, and compressed in the short time frame between now and the election. We’re asking ourselves, who are we as Americans?

Who are we anymore?

I’m an optimist by nature and experience. But it’s not an empty-headed optimism, it’s not “Oh, well, things are gonna be all right!” Things’ll be all right if we get ahold of ourselves and realize where we are. That there’s not been a time in my lifetime—with one possible exception—when I’ve felt that a lot of the world, if not most of the world, felt that we Americans had been humiliated. The one exception is when the last helicopters took off from the roof in Saigon. But now we have the double humiliation of being the most scientifically advanced country in the world, particularly in the field of medicine, and we’re in worse shape than anybody in the world in battling the coronavirus.

At the same time, contributing to this humiliation is that the world sees in President Trump someone about whom they can remark, How the hell did the great American people ever wind up with this as their leadership? Some of the world pities us, and some of the world is laughing at us.

You could make the argument, and I’m here to make the argument, that the country’s been damaged tremendously these last few years. Not all of it can be laid at the feet of President Trump, but it’s been damaged. But we adapt to change quicker than anybody on the record in the last probably 200 years. And I think we can do it again, but we’ve got to get busy. I come back to November. If we get our stuff together, if we get united on the big things, the core values, that we can overcome that damage.

If Donald Trump is reelected, it will raise the question, could the country survive—its key institutions, its basic spirit, its ethos? Could it survive another Trump term? Well, given my age, I probably wouldn’t be around to see all of it—but that might be a blessing.

ESQUIRE: The campaign is getting dirty—which doesn’t seem to be Biden’s nature.

RATHER: I agree with you, it is not in his nature. Former Vice President Biden has a lot of attributes that will stand him well in the campaign, but he is not a stand-toe-to-toe slugger. He has never been known for dirty campaigning. I’m not even sure he knows how to do it. That being the case, what he has to hope is that he can hire enough people who know how to do it.

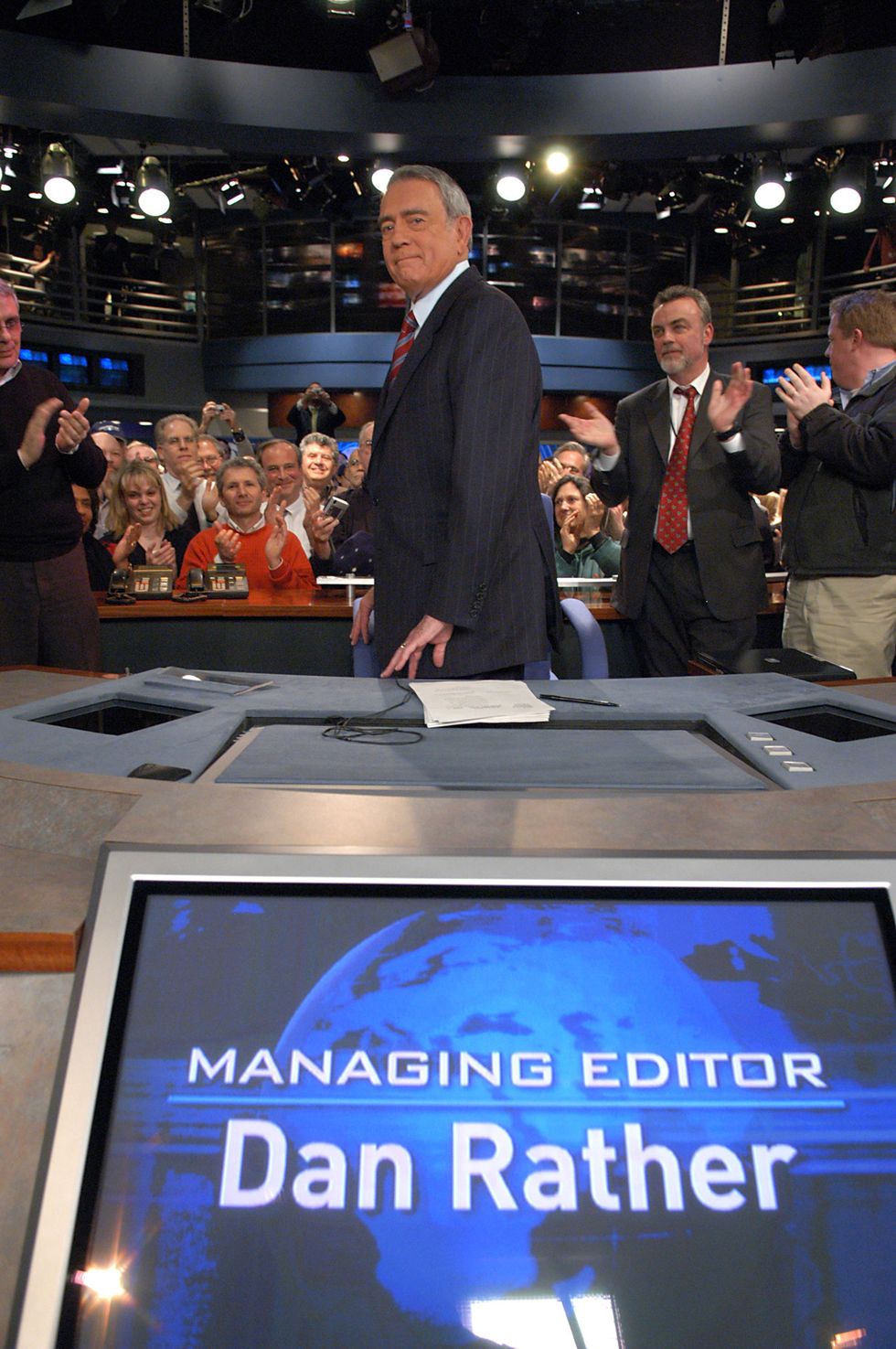

In 2005, Rather was pushed out of his job as anchor of the CBS Evening News, the job he’d held since 1981, over a report he did for 60 Minutes. The subject was then-President George W. Bush’s record in the Texas Air National Guard in the early 1970s. Rather’s report alleged that Bush had been admitted to a special unit that allowed him to avoid service in Vietnam, and had then deserted with no repercussions, all thanks to political strings pulled by his father, who at the time was the ambassador to the United Nations and then the chairman of the Republican National Committee.

There were proven technical and even journalistic flaws in the evidence Rather’s team found—but no one questioned the truth of what they were saying. Bush never disputed the veracity of the claims. It was a strange situation: By way of a possibly forged document, they had uncovered a damning truth about the sitting president.

Rather calls it “the darkest period of my professional career.”

ESQUIRE: When you left CBS, it seemed that there were people there who wanted you out and found something to pin it on. But you were given the option of letting others take the blame and staying on.

RATHER: When you take on the tough stuff, my attitude is, Look, we go into these things together. And for better or for worse, we come out the other end together. None of this pointing-at-each-other-in-the-loser’s-locker-room stuff.

I was noted, or notorious, for having that be the way I operate. And I wasn’t going to change during the Bush thing. I’m not tender about talking about it. Matter of fact, sometimes I think maybe I don’t talk about it enough, because there are people who have spread complete untruths about it.

But it ended the way it ended. I’ve never been bitter about it. Would I have liked it to turn out a different way? Of course I would have. But when I say I’m at peace with myself, it’s that we reported a true story. In the process of getting to the truth, we didn’t do it perfectly. Which is to say we made some mistakes. And our bigger mistakes were after the piece had played, we didn’t defend it effectively. We were rolled over completely in the battle for what was then the early stages of social-media primacy. We were routed.

Whatever my faults are and were, loyalty to CBS News was not one of them. CBS News had a long history of standing behind its reporting, even when the reporting was controversial, maybe especially when it was controversial, and even when the reporting had not been perfect. All of that went out the door and I was unprepared for it.

Nonetheless, what was then the new ownership—Viacom, a man named Sumner Redstone—was a big Bush supporter, and he made very clear that he wanted Bush to win the election. He couldn’t stand the thought of what we were doing, and he wouldn’t listen to “standing by the reporting.”

Now, a lot of people would say, Look, Dan, you’re putting the best possible face on this. And that may be. But I would say that anybody who looks into it knows at this point that what we reported was true. The two basic things were, did George W. Bush get into this so-called “champagne unit” of the Air National Guard as a way of avoiding Vietnam, through his father’s influence? That was one. True. The second: Once he was in, then he just walked away, he disappeared—he was gone for a year or more. Nobody walks away from the service.

Those were the two basic things that we alleged, and they’ve never been denied by George W. Bush nor by any close member of his family.

ESQUIRE: After those times when you’ve felt less than courageous, how did you change?

RATHER: I can be dumb as dirt. But at least I’m smart enough to know that I’m never going to be the smartest guy around. I never apologize for the education I had. The public schools in Texas gave me about all the education I was capable of absorbing.

I don’t always learn fast, but I learn good. This has happened repeatedly during what passes for my career.

Two examples: When I first started covering the civil-rights movement, I was unprepared. I came out of Texas, where they had institutionalized racism, strict segregation. And nobody ever called me an intellectual, and I damn sure wasn’t then. And yet I was placed into that cauldron—mind you it was something I asked to cover. “Put me on it.” We all know the journalist’s prayer, which is, Please, God, give me the big story.

When I first got into it, I thought, Well boy, we’re around these dangerous people, Klan rallies, cue-stick-bearing crowds of people, really bad situations. And at the very beginning, when people would ask where I was from, I would seldom say CBS, because CBS was sometimes called the Communist Broadcasting System, the Colored Broadcasting System. I accentuated a Texas accent. And once, and I’m not proud of this, somebody asked me, “Who do you represent?” and I just sorta blurted out, “the Houston Chronicle.” Which was a lie.

A later example of lacking courage would be in the run-up to what I call Gulf War 2. I was in a position to ask a lot of tough questions, and I didn’t ask enough tough questions. I put too much faith in what I thought was the honesty imperative of the presidency. Looking back on it, do I wish I’d been tougher? You bet. And particularly given my experience, it was an especially egregious mistake. And I regret that.

ESQUIRE: As a traveling reporter, what could you never be without?

RATHER: I don’t know whether I should say this—well, I’ll go ahead, it’s true. Particularly when I first started traveling long distances for CBS News, for the long flights to South Africa or Singapore, those flights where you could get drunk twice and still get off the plane sober—which every correspondent knows only too well—I tried to carry a picture of my mother and a picture of Jean.

And peanut butter. I’ve found if I can have water and peanut butter, at least in my own mind I can survive indefinitely. I always had it in my pack. In the dark days in Vietnam, on long plane rides.

Hurricane time, peanut butter time. No time to eat.

Susan Zirinsky is now president of CBS News, but she and I have a long history at CBS News, and on trips to Moscow, in the bad old days of the Cold War, I always insisted on having peanut butter, Vienna sausages, and soda crackers. A suitcase full of those three. And Susan used to lecture me, she’d say, Dan, this is ridiculous. You cannot survive on peanut butter and those god-awful Vienna sausages, as she called them. And I said, You tend to your news-gathering and I’ll tend to my diet.

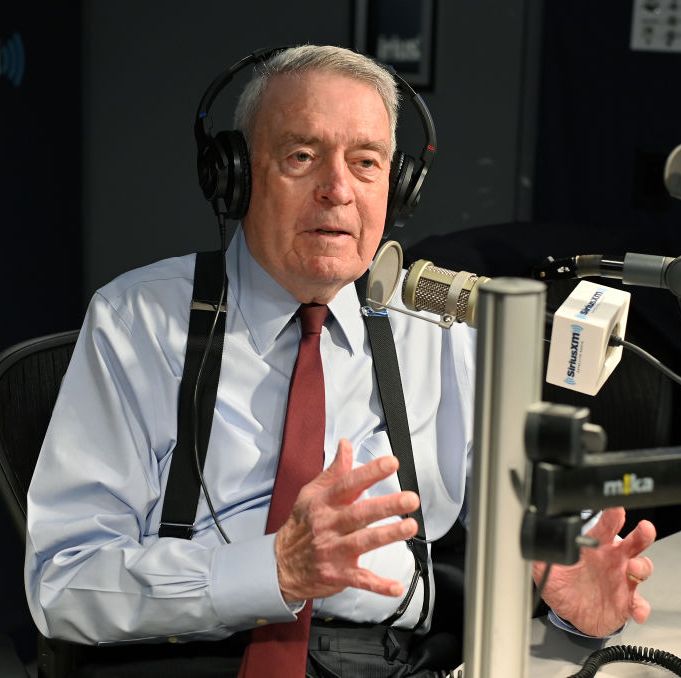

After CBS, Rather was hired by Mark Cuban in 2006 to produce and host an investigative-reporting show on HDNet, his high-definition television network, which became AXS.tv. Rather’s show was called Dan Rather Reports and ran for about seven years—it was, he says, “a dream job. Going to work for Cuban was one of the best things that ever happened to me.”

“Dan has touched every important moment in the lives of GenX and Boomers,” Cuban says. “He has seen what makes us who we are, and he has the ability to convey it in a way we all can understand and learn from. I wanted to give him a voice.”

Later, Cuban convinced Rather to host a show called The Big Interview, in which Rather interviewed mostly musicians of a certain age—Steve Perry, Ricky Skaggs, Joan Baez, Robert Plant, Neil Young, Dickey Betts. It was an odd pairing of subject and host, and at first Rather resisted. “Pretty much if Bob Wills or Hank Williams didn’t sing it, I didn’t know it,” he says. “Furthermore, while I like to sing, I can’t carry a tune in a bucket with a lid on it.”

But the show worked, and he’s done more than 150 episodes so far.

I asked Cuban why he was so certain the show would work. “Dan is a walking encyclopedia,” he says. “If Elon Musk’s Neuralink could search Dan’s memory, the output would put Google searches to shame. His understanding of history and the people in it, and his ability to connect with anyone, are beyond incredible.”

Rather needed to form a production company for his work with HDNet. He named it News and Guts, and he still runs it today.

ESQUIRE: You’re almost 90, and you’re still at it. On every platform imaginable. Always finding a new way to get your voice out and do your work. Why are you still doing this?

RATHER [with no hesitation]: Because I love it. For whatever reason, I’ve had a lifetime passion for covering news. That’s never abated. One of the mildly surprising things to me, if anything the passion burns brighter and harder now than perhaps it ever has. And in recent years, I’ve enjoyed the work as much or more than I ever have. It may be damning with faint praise, but I have come to believe that some of the best work that I’ve done has been done in these last few years.

Among the things I am not, I am not a philosopher. I mean, what you’ve got here is basically a reporter who got lucky. But it may be that what my wife, Jean, calls TR—time remaining—comes into that. Without apology I’ve always wanted to be a great reporter. That’s sort of a navigation star. It’s not that I think that I’ve ever been one, or even am ever going to become one. But you have to keep striving, moving toward it, trying every time.

So when you say, Why do it? I’m still trying to be a great reporter.

![Dan Rather [Misc.] tv image of cbs newscaster dan rather giving analysis of pres nixons resignation speech photo by gjon milithe life picture collection via getty images](https://hips.hearstapps.com/hmg-prod/images/gettyimages-50604664-1600871773.jpg?crop=0.888xw:1.00xh;0.0476xw,0&resize=980:*)