This week, we are celebrating Radiohead’s OK Computer with essays, videos, interviews, visual artworks, and more. Check out all of the coverage here.

Radiohead could have stopped making videos. With their music growing stranger and more critical of the capitalist enterprise around OK Computer, they could have simply opted out of such glorified television commercials and their attendant pomp and flash. But instead of scoffing at the worst of MTV, they took advantage of the channel’s reach to challenge, warp, and fundamentally reorganize millions of impressionable teenage minds.

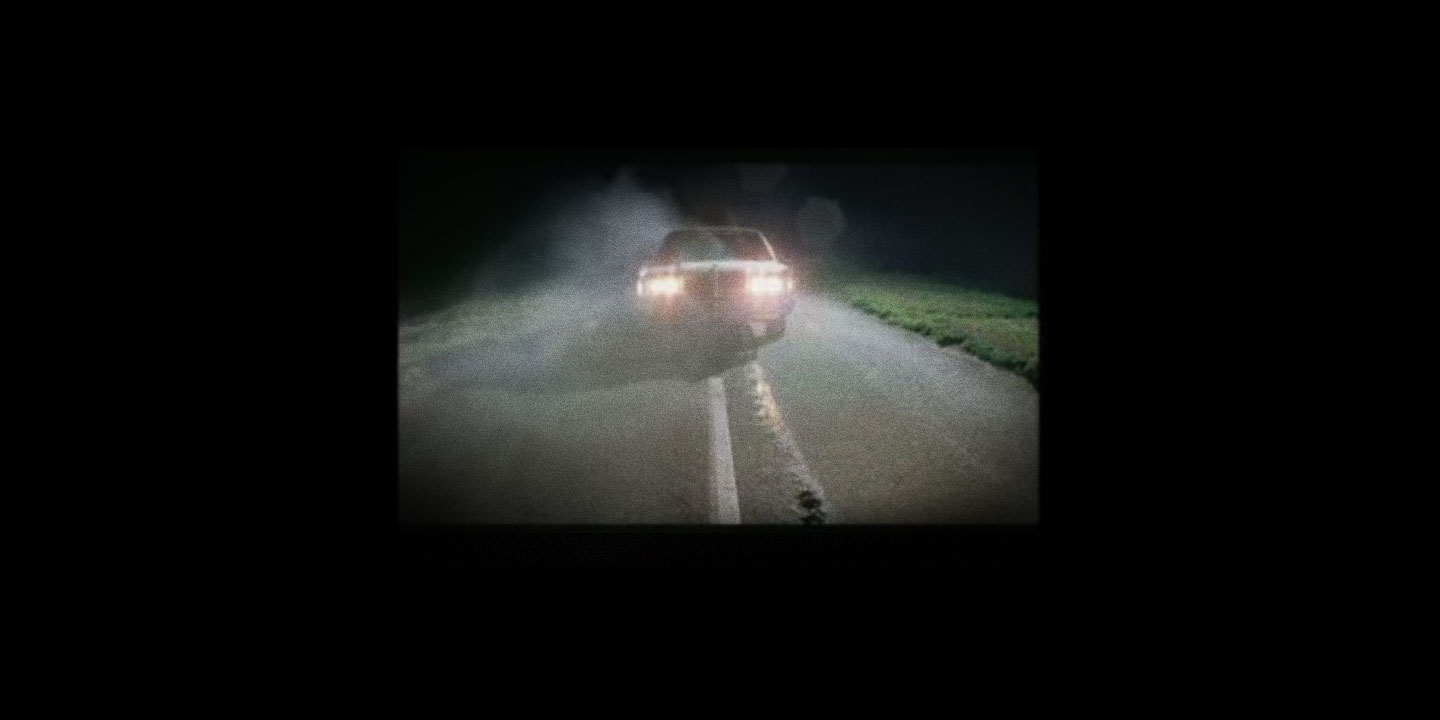

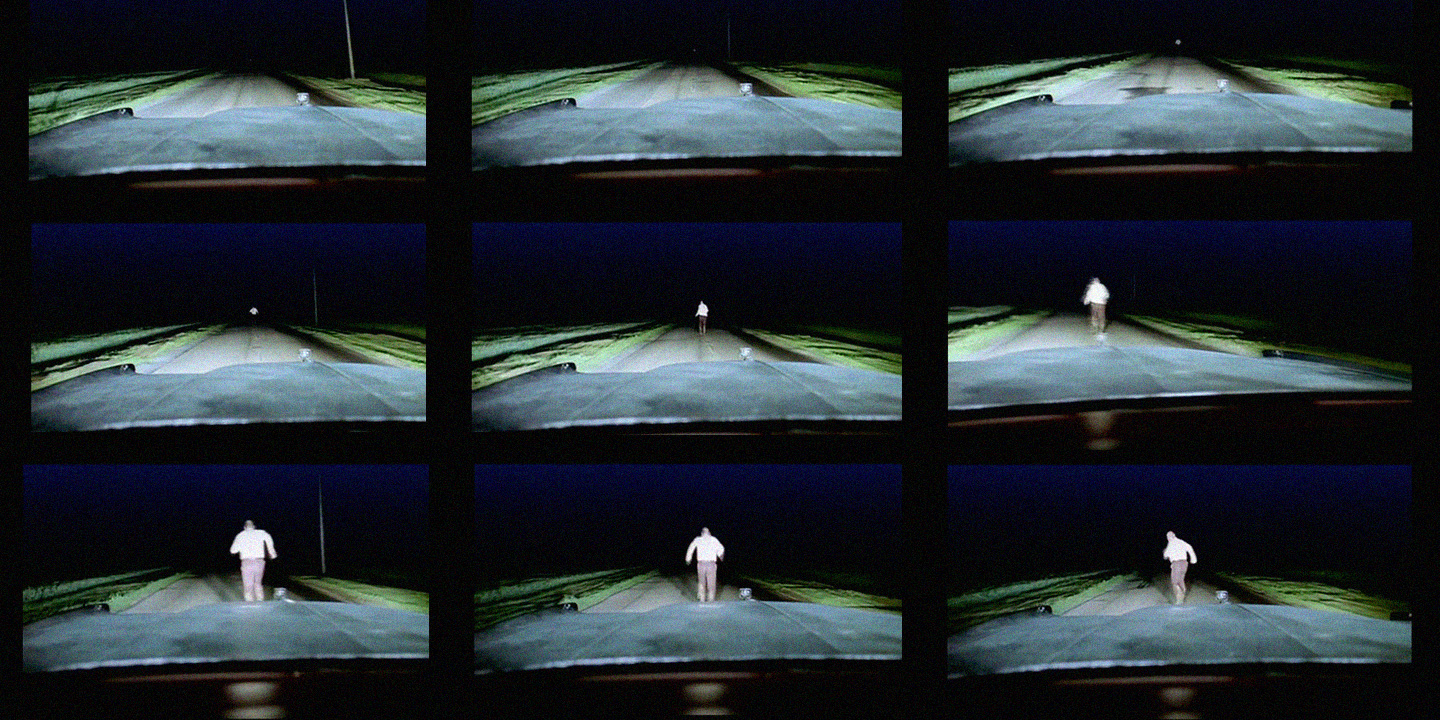

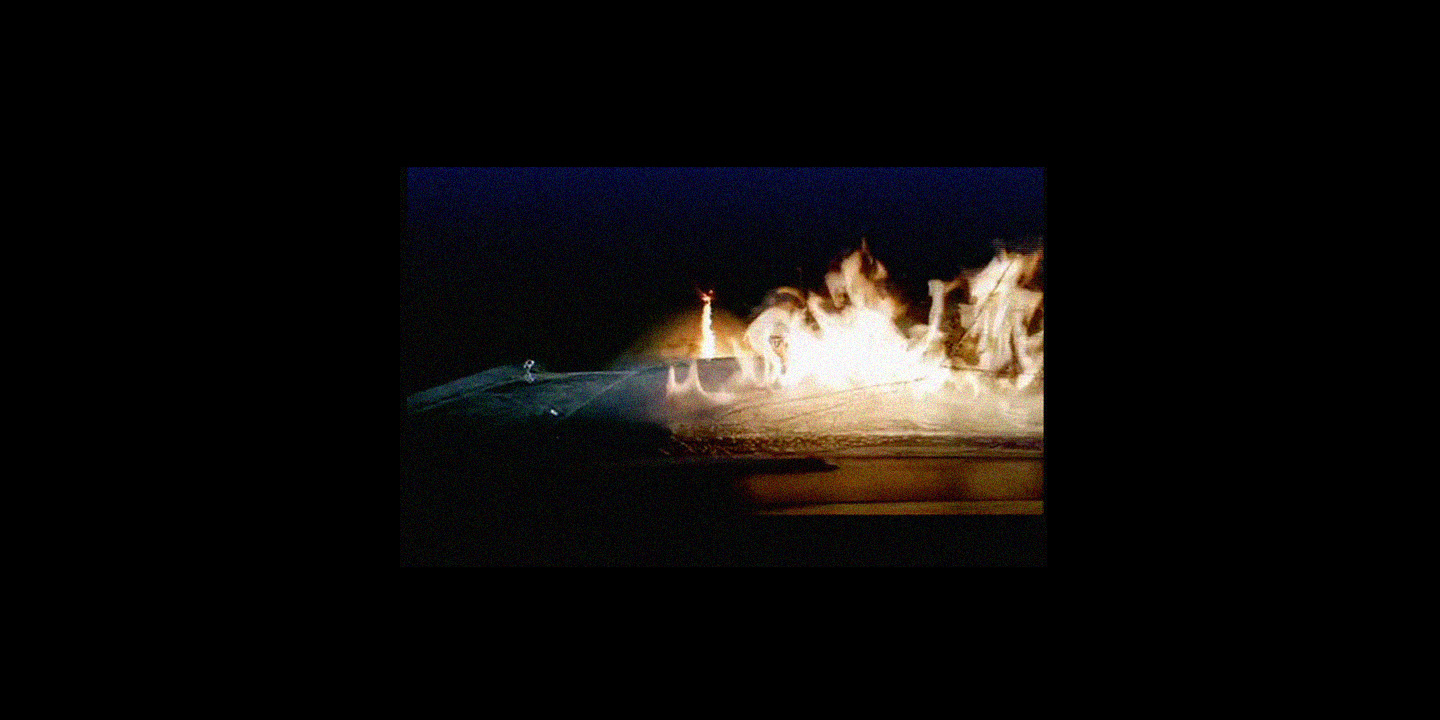

There was the animated insanity of the “Paranoid Android” video, which imagined a surreal dimension filled with politicians in barbed thongs, humping rats, and a drunk dude with a head coming out of his stomach. And the one-shot stunner “No Surprises,” in which Thom Yorke nearly drowns for our voyeuristic pleasure. But perhaps the most trenchant visual to come from OK Computer is director Jonathan Glazer’s menacing parable for “Karma Police.” In it, a grizzled man is slowly stalked by a 1976 Chrysler New Yorker, before fortunes are flipped amid a blaze of fire. Along for the ride is Yorke himself, who plays the angel—or devil—singing from the blood-red backseat; most of the video is shot from the driver’s point of view, making each and every viewer complicit in the unfolding terror. Filmed on a desolate road in Cambridgeshire, England, the video’s ambiguity—it begins in medias res, and it’s impossible to know who to root for—lends itself to endless interpretation, and to timelessness.

Making its debut on MTV’s “120 Minutes” on September 21, 1997, the “Karma Police” video came along in an era when vanguard bands and directors were encouraging each other to push at the format’s limits on a regular basis. (An influx of industry cash thanks to the CD boom did not hurt—the clip’s budget was around $200,000 at the time, a generally unheard-of sum for a video nowadays.) And Glazer was among a generation of music video auteurs, including Spike Jonze, Michel Gondry, and Mark Romanek, who helped to turn an inherently craven medium into something genuinely inventive.

Twenty years later, the “Karma Police” video still feels frighteningly up-to-date; as long as there are big guys and little guys and unexpected twists of fate, its power will endure. Here’s the story behind the video from those who were there.

DILLY GENT [Radiohead’s video commissioner, 1992-2008]: When I first met Radiohead, they were all living in a house in Oxford together, just like any other young band. I got a job as a video commissioner at Parlophone Records in ’92, and they joined the label that same week. So I was due to start on the Monday but I was told, “Oh, can you just zip up to Oxford on Saturday? You’ve got to meet this band, and we’ve got to shoot a video.” That was “Creep.”

At first, they were really just making the videos they wanted to make. “Pop Is Dead” is literally a treatment that Thom wrote, down to every frame—we had the entire Radiohead fan club carrying him across the Oxford Downs in a glass coffin. I was doing a terrible job, but I wasn’t really concerned because we would just go off and make something. In the early ’90s, we probably thought those videos were all right, but looking back at them now, we all just want to die.

I remember an early gig in Amsterdam where there were six people in the audience. The band was still kind of working out how to play their instruments. I just thought, They’re really nice, sweet, low-key boys. The singer’s got a phenomenal voice, and they’re kind of good. But then they worked so hard and really flourished. By the time the second album came along, it was leaps and bounds ahead. And then, third album, another leap. And at the same time I was getting more confident and trusting my taste more. And since me and Thom have very similar taste, the process of making videos became very easy.

MATT PINFIELD [former MTV VJ and host of “120 Minutes”]: When I was at MTV, the industry was trying to write off the band as a one-hit wonder with “Creep,” but I absolutely loved The Bends as well. We would get heat from other record companies, they would say to us, “Our record sold 20,000 more than Radiohead this week, why do you keep promoting their record?” And we said, “Because it’s great!” We stood our ground, and it was something that the band really appreciated.

When Thom handed me a gold record for The Bends, he was actually in tears. He said, “I know you guys took a lot of shit for standing behind this album and these videos and the band, and I just want to tell you how much I appreciate it.” That’s what this is really all about. And of course, we were right there with OK Computer as well. I’m very proud of having a gold record for OK Computer and for The Bends. It’s not just about material things, I believe in the records and the band so much.

[1] Source: The Independent, September 14, 2006

THOM YORKE: [“Karma Police”] is for someone who has to work for a large company. This is a song against bosses. Fuck the middle management! [1]

[2] Melody Maker, May 31, 1997

JONNY GREENWOOD__:__ It was a band catchphrase for a while on tour—whenever someone was behaving in a particular shitty way, we’d say, “The karma police will catch up with him sooner or later.” [2]

[3] Q Magazine, October 1997

THOM YORKE: “Karma police, arrest this man.” That’s not entirely serious, I hope people will realize that. [3]

DILLY GENT: I did not know there was any humor attached to the song. The great thing about Radiohead is I never had a clue what their songs meant; I never asked, Thom never said. When I present a treatment to a lot of bands now, they’ll say, “Oh, but the song’s not about that.” And you go, “Well, we’re not making a documentary here.” With Radiohead, I could barely pick out the words, so the videos are made from the feeling of the music and what it conjures up.

MATT PINFIELD: Radiohead were a band that showed you how music videos could be art, that it didn’t just have to be somebody spending $3 million on a Meatloaf video that looks like an action film—nothing against Meatloaf personally.

JONATHAN GLAZER: I was flown over to New York to see a private screening of David Lynch’s then new film Lost Highway because Mr. Manson wanted the video to relate to it somehow. Anyway, all I remember from that screening were the opening credits of a rushing road beneath the camera. Next thing I knew it was the closing credits—I’d had a big night, no sleep, and nodded off. So yes, that scene must have entered my subconscious, and the idea for “Karma Police” came out of it. It’s the only time I’ve written something for one artist and ended up making it for another.

RANDY SOSIN [former video commissioner at A&M and Interscope]: I remember having dinner with Manson’s manager right as the “Karma Police” video came out, and he told me that Jonathan Glazer had pitched a similar idea for a video with Manson for his song “Long Hard Road Out of Hell,” which would make sense with the car on fire at the end and everything. I had a similar thing happen once, when Michel Gondry pitched an idea for Soundgarden’s “Burden in My Hand” that later became a Cibo Matto video called “Sugar Water.”

As far as why Manson passed, I just feel like he didn’t necessarily want to be a piece of another artist’s work. I don’t remember him ever saying, “Oh, why didn’t I make that video?” It’s just that music video directors in particular tend to have a very specific vision and they see which artists are willing to go there.

Watch a video featuring fun facts about the "Karma Police" clip drawn from this oral history.

DILLY GENT: After he directed the video for “Street Spirit,” from The Bends, Glazer and I became really good friends, mainly because we fought a lot about that video—but in a good way. So we would meet up, and he said, “I’ve got this great short film idea.” It was exactly the idea that you see in the video, and I absolutely loved it. Though I didn’t even know we were going to do it with Radiohead at that point. Then “Karma Police” came along as a track, and I sent it to Jon, and he wrote it out, and I said to the band, “You need to do this, it’s a piece of perfection.”

JONATHAN GLAZER: I was interested in trying to shoot something very simple, short story-ish. Where the whole narrative could be contained within a single sentence.

DILLY GENT: Jon’s a great storyteller. I remember being in his house when he was telling me about a scene from [Glazer’s 2013 film] Under the Skin before it was made. It was a bright sunny day, kids running around the kitchen table, couldn’t have been a more cozy environment—but I swear to god I thought I was going to die from horror, because he described it so vividly. There were just chills going down my back. I was like, “I am never going to see this damn movie if I can’t even handle you describing it to me in your kitchen.”

SEAN BROUGHTON [“Karma Police” visual effects supervisor]: I might have stared blankly at Jonathan for a moment when he first told me the idea for the video. It is a really simple idea: A guy in a car is chasing someone, then you’re now being chased by that guy. When you’re given something like that, there is such an element of trust in it, and the execution of it is everything. You could have a different director shoot that same piece and it could be terrible. But by the time Jonathan is telling the story to someone, he already has pretty much the finished edit in his head. “Story is king” is the mantra that we always used to chant in those days.

DILLY GENT: When Jon told me the idea in the café, I was going, “This might be your first cheap video!” I thought you could just attach a camera to the bonnet of the car, get a guy running, some petrol, fire. But no. The idea was really straightforward, but the production was a monster.

The running actor was flown in from Hungary. He wasn’t local. And he kept getting a cramp and having to have some horrible injections put into his leg so he could keep running.

SEAN BROUGHTON: The actor burned his thumb quite badly having done many, many takes of lighting that book of matches with one hand behind his back. He walked out with a fairly disfigured thumb by the end of the shoot.

DILLY GENT: The car looked like a futuristic robot. That in itself was probably half the budget. And then Thom wore a little khaki-green T-shirt under a leather jacket—and we had a whole truck full of khaki-green T-shirts for him to choose from.

[4] Details, September 1997

THOM YORKE__:__ This video alone would cost us a really nice house somewhere. [4]

SEAN BROUGHTON: Jon wanted to have the fire chase the car at the end of the video, and as effects supervisor, I had to figure out a way for that to happen. We couldn’t really have a quarter mile of fire chasing this car because you’d light one end and it would burn the full distance in a few seconds and probably set fire to the car and blow it up.

So we actually shot the fire in a dark shed with a locked-off camera during the shoot, about a half mile away from where Thom was. Then we had to actually track that fire into the shot. We had about 100 cones that were covered with a reflective tape, and we put two down on each side of the road for a quarter of a mile. The angle of the cones were such that when the car headlights shone onto them, the tape would glow, and we used those cones in order to track each section of fire into the roadway. There were people looking at us like we were mad: “Why are there people struggling to carry 30 boxes of cones into the countryside? What the hell are you doing? Why can’t you do it another way?”

We worked all night on it. At about one o’clock in the morning, Jon turned up, having not seen any part of the fire, and sat there in silence and watched it for the first time. He just went, “Nailed it.” That was it. It was a good feeling.

DILLY GENT: At the time, Thom really looked a bit like an alien. He was just changing his hair; you can see his scalp. And the lighting was beautiful. With anyone else directing, it would have just been a bloke in the back of the car, but they made him look like this otherworldly human being. With Glazer’s work, you just want to grab each frame and put it on your wall. Nothing will ever be dated about that video.

Watch a visual effects breakdown of the fire sequence in the "Karma Police" video, courtesy of Sean Broughton.

SEAN BROUGHTON: Any piece of good art is something where everyone sees something different in it, and to have a story that is so simple does lend itself to you reading into it.

JONATHAN GLAZER: I’d say the ‘driver,’ the presence at the wheel, is more like a robot. Thom’s the storyteller. In my mind, he’s not even there.

SEAN BROUGHTON: There is the lyric: “This is what you’ll get when you mess with us.” It could be applied to bullying—the kid that got sand kicked in his face suddenly turns and is a bodybuilder made of muscles. When you’re young, you’re certainly full of teenage angst, and this song and video offers a very easy translation for anyone’s feelings of unfairness, which is one of the earliest and strongest emotions that we have. When you see it acted out with a successful turning of the tide, that’s always appealing.

DILLY GENT: Back then you had curated platforms like “120 Minutes,” and the labels could see the direct line from the video being seen and album sales going through the roof.

SEAN BROUGHTON: That time in the ’90s really was the golden era. It was when people could use the full breadth of talent that was available in the industry purely for artistic reasons. We weren’t necessarily trying to sell toothpaste to the millions. It was something that was really a work of the heart, that people really believed in, and it spurred people on to do bigger and better things. And most of it was done with no expectation of monetary reward. It was done purely for the love of it. That’s hard to find.

That ilk certainly disappeared around the time that the Spice Girls all broke up. The money left the industry. People weren’t buying that many records. It all changed. People wanted green screen videos. The bubble had burst.

DILLY GENT: Once there was no longer a focused place where people could see videos, there was no direct line from a video being made to albums being sold. And that’s when all of the video budgets plummeted. I mean, I remember having £50,000 to make a Radiohead video and thinking, God, I've only got £50,000, I’ve no idea what we’re going to do. Now I’m trying to make two videos for $10,000.

RANDY SOSIN: Videos aren’t bad now, but I just feel like the world has changed and videos have stayed the same. I wish it would evolve as a medium because it is a powerful tool. Opportunity is there, I just don’t see a lot of people taking advantage of it.

DILLY GENT: It’s very hard to make that level of music video now, because there’s so much fear attached to the creative process. Everything has been diluted now, video-wise. It’s a massive challenge for me to make a creative video. I don’t even know if it’s possible anymore.