HIGHLIGHTS

- Louisiana going wrong direction, spending more on nursing homes as rest of nation funds alternatives to institutionalization

- State nursing homes frequently ranked 50th in the nation

- Nursing homes have seen millions in increased funding, as hospitals, higher education, prisons see budgets slashed

- 30 percent fewer home and community based providers than 2012 because of budget cuts and tighter restrictions

- NOTE: This is the first in a three-part that explores the political influence and quality of Louisiana nursing homes and the resulting impact on Louisiana's most vulnerable population

The past 10 months have ticked away at a torturously slow pace for Kenny Johnson, who prayed every day he’d get the call telling him it was time to leave the nursing home.

Johnson, 24, lived there among people three times his age, some of them older than his grandparents. Sometimes he played bingo. Or he’d read books to a woman who lost her sight.

He did what he could to stay busy. Because when he was idle, Johnson would get depressed.

"I'm 24 years old. I had to have my birthday and Christmas and New Year's in here. I was supposed to be out there with my family," he said. "I can't live here. I can't stay here. This place depresses the heck out of me."

Johnson was stuck in a Shreveport nursing home because he suffered grievous injuries in a car accident at 22. Johnson, who was pursuing a business degree from Louisiana Tech University, where he played football, had been working as a construction foreman at the time.

Moving into a nursing home at that age was unimaginable to him. And yet, the state left Johnson with few options. The wreck rendered him paralyzed from the waist down and partially paralyzed in his arms. He needs assistance with menial tasks like eating, brushing his teeth and getting dressed. He can’t get from his bed into his motorized wheelchair alone. And the relatives who had been helping him at home needed to get back to their jobs.

Without being able to work, Johnson couldn’t afford private care, so he depended on Medicaid. And in Louisiana, more than 32,000 people are ahead of him on wait lists for publicly funded home- and community-based support programs, the main alternatives to nursing homes for the elderly and physically disabled. Such programs allow people like Johnson to stay in their own homes, with part-time help from nurses and other aides. The length of the waiting list meant Johnson could have waited a decade to receive care at home.

The nursing home was able to take him right away.

Johnson is unusually young for a nursing home resident. But he identified with a lot of his fellow residents in one key respect: Many of them said they would have been much happier at home, with help, but that wasn’t an option. And they felt trapped.

Louisiana's failure to properly support home- and community-based programs is unusual. It also puts the state at risk of violating federal laws that protect the civil rights of the state's most vulnerable people.

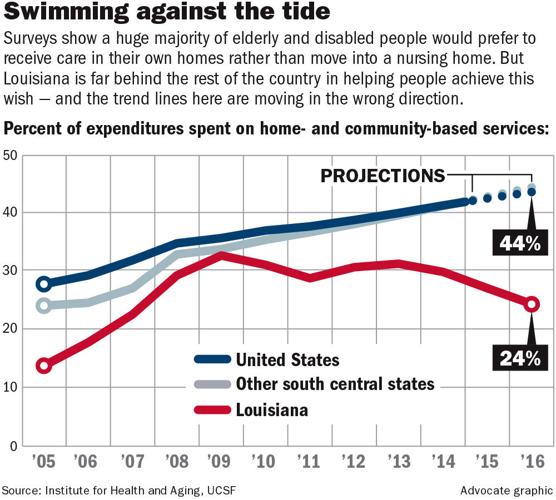

Virtually every other state has been investing an increasing share of taxpayer dollars into home- and community-based health care. Such programs are widely preferred by people who want to live independently — 90 percent of respondents in an AARP survey of Louisiana's voters — and most states have embraced them because they also are much less expensive than nursing homes.

Nationally, "there has been a shift away from institutional spending and institutional participation toward home- and community-based service spending and participation," said Steve Kaye, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco's Institute for Health and Aging. "Louisiana is very much an outlier."

The root of the problem is a long list of financial policies and laws in Louisiana that heavily favor nursing homes. These special protections, many of them unique to Louisiana, are a testament to the strength of the state’s nursing home lobby, long a leading source of campaign cash for the state’s politicians.

"There's a bias toward institutionalization — both in our policies and our funding," said Karen LeBlanc, who has written critical reports for the Louisiana Legislative Auditor's Office about the way the state funds long-term care.

Funding favors nursing homes

People who are unable to take care of themselves and who rely on Medicaid generally have two options — either go into a nursing home or hope for a slot in a home- or community-based program.

But in Louisiana, odds are they'll end up in a nursing home because that's where the state's money goes.

This year, the 259 nursing homes in Louisiana that accept Medicaid are slated to take in more than $1 billion in public funds. That's roughly 4 percent of the overall state budget and about 10 percent of the state’s Medicaid budget — a bigger slice than any other sector, including hospitals and physicians.

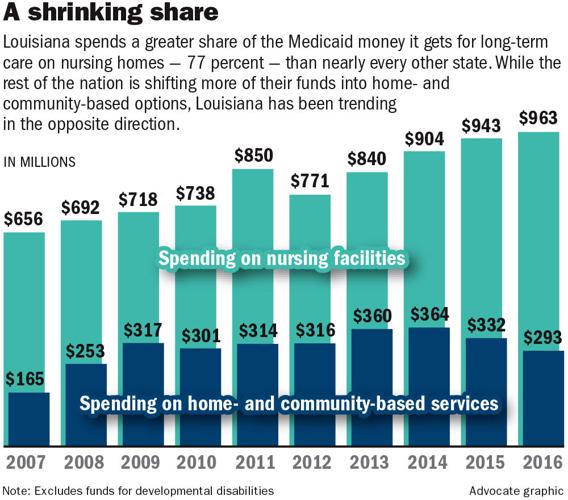

Nursing homes get 77 cents of every dollar that’s available for the elderly and physically disabled. Home-based providers take in the remaining 23 percent, a share that peaked in 2009 and has gotten smaller every year since 2013.

For the rest of the nation, the split is typically closer to 60 percent for nursing homes and 40 percent for home- and community-based providers. And in most places, the gap is narrowing.

But Louisiana has been moving in the opposite direction — the wrong direction, in the view of most experts.

From 2009 to 2016, total home- and community-based funding for the elderly declined by 7 percent, even as nursing home funding increased by 34 percent. Even so, the number of people receiving community-based care grew by more than a third — from 15,000 people to 21,000 — while the number of people in Louisiana nursing homes stayed flat. That’s because the state has built in generous annual per-bed raises for nursing homes.

"The concern I have right now is we're moving backward," said Hugh Eley, a longtime former administrator with Louisiana's Department of Health who served for eight years as assistant secretary for aging and adult services under Gov. Bobby Jindal. "Every other state is moving more in the direction of less emphasis on institutional care, and we seem to be reversing the trend."

The funding increases for nursing homes are all the more eye-popping in the context of Louisiana's budget, which has seen year after year of cuts. Over the past eight years, state lawmakers increased funding for nursing homes by $245 million, even as they slashed aid to Louisiana’s universities by $542 million, cut the Taylor Opportunity Program for Students scholarships by $90 million and pared back spending on state prisons by $77 million.

"Nursing homes are an outlier in the (Medicaid) program," said Jeff Reynolds, undersecretary for the Department of Health. "Their rates have gone up where everyone else has either gone down or been flat. Most have gone down."

That means doctors and services supporting the state's poorest residents — in rural clinics, for children's services and mental health services, for instance — have all been cut so aggressively that federal authorities told the state they will not approve any further Medicaid rate cuts. Louisiana has cut its rates more frequently than any other state in the country.

Amid those cuts, Louisiana's nursing homes have seen Medicaid rate increases every single year for more than a decade. Today, the average nursing home receives about $173 per person, per day — an increase of 54 percent since 2006.

But Mark Berger, president of the Louisiana Nursing Home Association, said even that allocation is still quite modest. Louisiana consistently ranks fourth-lowest in the nation for nursing home reimbursement rates, he said.

"Our costs are not runaway," Berger said.

Eley and other health care officials counter that Louisiana's lower reimbursement rates reflect lower business costs here.

Not only are Louisiana’s spending priorities out of step with other states, they’re out of sync with demand. About one-fourth of Louisiana's nursing home beds are vacant and have been for years. Meanwhile, the waitlist for home- and community-based services for the elderly is almost twice the number of people it actually serves.

"People are waiting between three and 10 years to get these (home- and community-based) services because they're on a waiting list, and some of them never get those services because they die," LeBlanc said. "What it means is that we're spending a lot of money in nursing homes for a service that people don't necessarily want."

Quality concerns with nursing homes

If nursing homes have been held in high favor by Louisiana lawmakers, it hasn’t translated into high-quality services.

The state's nursing homes are routinely ranked as among the worst in America. The federal government rates almost half of the state's nursing homes as either "below average" or "much below average" based on staffing, health inspections and quality measures.

A 2011 report on long-term care services across the country found Louisiana had the highest percentage of nursing home residents with bed sores. Bed sores are usually the result of inadequate care.

Louisiana also ranked among the worst in the percentage of its nursing home residents who were physically restrained and in the proportion who had to be admitted to a hospital. The state’s nursing homes also got poor marks for the frequency with which staffers hand out antipsychotic and anti-anxiety medications.

Johnson, the 24-year-old resident who stayed at Pierremont Healthcare Center in Shreveport, entered the facility hoping it would speed up his receipt of a Community Choices Waiver, a home-based program. People in nursing homes get priority on waiting lists, but Johnson still ended up waiting more than seven months before he was promised a slot, and he wasn't able to leave until this week.

And unlike most residents in nursing homes, Johnson had an advocate on the outside helping sort through the bureaucracy and aggressively making calls on his behalf.

On top of his feelings of isolation, Johnson was appalled by what he considered inadequate treatment in the nursing home. Johnson shared his room with a 15-year-old with virtually no cognitive awareness or physical abilities. Johnson said that on multiple occasions, his roommate aspirated and vomited on himself because he was unattended on a feeding tube.

"I'd be pressing the button for help, and sometimes, people won't come for hours," he said. "That hurts to watch."

Johnson also said physical therapy in the facility was almost nonexistent. After his accident, he received outpatient physical therapy and started to regain movement in his hands and arms. But he said he regressed after arriving at the nursing home, where he received almost no personal attention.

Johnson said the nursing home often smelled of urine and excrement because residents would have accidents and staff would let them sit in it for hours. Often, people with paralysis need help in moving their bowels, and they would sometimes wait days to get that assistance.

"No one wants to sit in a bowel movement or urine," said Mitch Iddins, an advocacy worker who helped Johnson get his waiver. "These people have their dignity."

Brian Lee, an attorney representing Pierremont Healthcare, said the nursing home categorically disagrees with the characterization of its care by Johnson.

"After reviewing the situation carefully, our Pierremont staff can confidently affirm that the patient and his roommate have received high-quality care from our nurses, nurse aides and therapy department on a daily basis," he said. "We believe that extends to all of our residents at Pierremont."

Christine Bruce, 57, of Shreveport, landed in a nursing home after health problems from her diabetes left her disabled. As she grew stronger, she became increasingly frustrated with her surroundings, but she said that over a three-year period, no one from the nursing home had ever told her that home- and community-based services were an option.

"I thought I was going to have to stay there forever, and that's exactly what they wanted," said Bruce, who stayed at Vivian Healthcare Center in Caddo Parish.

It's the nursing home's obligation to let residents know about other options, state health officials said, but a recent investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice found that many Louisiana nursing homes were failing to do so.

Berger said he's confident that nursing homes are fulfilling their requirements — adding that some operators of nursing homes have even gotten complaints from people who, upon being told of other options, erroneously thought they were being forced to leave.

But Bruce said she learned about at-home services only by talking with people who were visiting their relatives.

"Is Coca-Cola required to tell people they should drink Pepsi?" Lee asked rhetorically in an email. Lee is an attorney for Nexion Health, the parent company of both facilities where Bruce and Johnson stayed. "There are no laws which say a nursing home is required to help patients examine competitors' care options."

In fact, federal regulations do require any nursing home receiving Medicaid to identify people interested in transitioning back to their communities. And the recent DOJ investigation, released in December, found that Louisiana nursing homes were largely failing to ask residents if they wanted to leave.

In at least one nursing home, the report said, staff was trained to record that a resident said "no" when asked if they wanted to leave, against their wishes, if a staff member felt the resident was better served with institutionalization.

In Bruce's case, after she expressed a desire to leave, it took two years to receive a Medicaid waiver for a home-based program. In December, she moved into an apartment where workers visit her for a few hours every day, helping her clean and cook and taking her to run errands.

After she left the nursing home, her new doctor told her "about half the medicine I was taking there was nonessential."

Lee disputed the allegation, noting that medication is prescribed by attending physicians, and nursing homes are required to follow a resident's plan of care.

Berger said he doesn’t think the state’s poor rankings reflect reality. He said other metrics show Louisiana's nursing homes are meeting national averages in most categories. He also said the facilities are making great strides to improve on their weaknesses. For example, the use of antipsychotic medications has decreased by 38 percent, and the number of registered nurses working in Louisiana facilities has increased by more than 15 percent since 2011.

"Quality is something you never stop working on," Berger said. "We want to continue doing better and we will. But as it relates to the rest of the nation, we're doing a good job."

But Kathy Kliebert, the former head of the state Department of Health, which oversees nursing homes, doesn’t share Berger’s sunny view.

"We do have some really good ones that are trying really hard to give people good services, but we have some really poorly run ones, in terms of their physical environment and in terms of staffing," she said. "There's some poor quality in the nursing homes, so I think the rankings are an accurate portrayal."

Kliebert added that she's been shopping for nursing homes for her mother in recent months. Asked if she'd send her mother to a facility in Louisiana, she said: "There are several that I would. But there are many, many that I would not."

Programs get decimated

Even as nursing homes have seen their state rates continually rise, home- and community-based services have had their rates slashed. Many have been forced to shut down because they can't make a profit.

Jacqueline Blaney, CEO of Independent Living Inc., a Baton Rouge-based home- and community-based health provider, said rates have been cut so severely that she had to eliminate all forms of paid leave and roll back starting salaries.

The rate cuts are driving providers out of the market and making it hard for the existing ones to keep a full staff, she said.

"When Jack in the Box is advertising for $10 an hour and I have to start people at $8 an hour, it affects recruitment and retention," she said. "The workforce issue is a huge crisis, and there's no way to address that except with a rate increase."

Louisiana serves about 21,000 people in home- and community-based services for the elderly and physically disabled. Among them is Jolene Perryman, 74, who moved back to her home in Bordelonville in Avoyelles Parish at the end of January to spend the rest of her days with her beloved partner Jessie Lueallen, 77.

Perryman spent 13 months in a nursing home. She has a brain tumor, lung cancer and a broken hip. Taking care of her was too much for Lueallen alone. But the two, who have known each other since Perryman was 5, said they were lonely without each other.

"She told me, ‘I don't want to die in this nursing home. I want to go home,’ ” Lueallen said.

Perryman eventually was approved for a waiver that pays for 7.5 hours of home- and community-based services every day. The workers help her bathe, use the restroom and get dressed. They also help with cooking and cleaning around the house, and sometimes they take Perryman to doctor’s appointments.

"I wanted to be in my own home. I wanted to be with Jessie," she said.

Advocates say home-based programs give people like Perryman, a highly dependent patient, the maximum amount of freedom and choice. But the state doesn’t always put a priority on that.

Kim Jones moved to Louisiana last year to become executive director of The Advocacy Center, a New Orleans-based nonprofit that serves the elderly and disabled. She was amazed at how blasé Louisiana officials can be about sending people to nursing homes for the rest of their lives.

"The state promotes longtime institutionalization," Jones said. "But there's just no shortage of research that talks about the benefits of social interaction. Being in your own housing and surroundings yields better health outcomes; it gives you more opportunities for community activity and engaging in the economy."

Today, there are 229 fewer home- and community-based providers than there were in 2012. That’s a drop of about 30 percent. Most observers attribute the whittling to a combination of state funding cuts and stiffer regulations for providers.

"It makes me very sad for the people who believe the state has their best interest at heart because they are being terribly betrayed," Blaney said. "People say the state doesn't have money, but the state chooses to put their money in the wrong place, and the public's interest is being sold out."

Federal lawsuit

Giving people options outside of nursing homes isn't just a feel-good measure — it's the law. And it's one Louisiana previously has violated.

Under the U.S. Supreme Court's 1999 Olmstead decision, states must fund and provide services for people with disabilities in noninstitutional settings.

"I think they're in danger of violating the Olmstead decision and have been for some time now," Nell Hahn, the retired director of litigation for The Advocacy Center, said of Louisiana. "The federal law protects individuals from being forced and segregated in the community. When you compare our percentages to other states, it just gives you an idea of the magnitude of the problem here."

In 2000, The Advocacy Center sued the state in federal court on the grounds that Louisiana was unnecessarily and unconstitutionally placing people in nursing homes because of a lack of resources for community-based services. The state settled and began pumping tens of millions of dollars into new community-based services. That effort peaked in 2009, when about 31 percent of Louisiana's Medicaid dollars for the elderly and disabled went to home- and community-based services.

But the suit ended that year, and the state has been backsliding on support for community-based programs ever since. During the past fiscal year, those programs got just 23 percent of the Medicaid budget.

And in December, the U.S. Department of Justice put the state on alert when it wrapped a two-year investigation — the same one that found issues with identifying people who wanted to leave — that found problems with the state's practice of housing about 4,000 people with serious mental illnesses in nursing homes.

"Louisiana's unnecessary reliance on nursing facilities violates the civil rights of people with serious mental illness," the report said. "By contrast, community integration will permit the State to support these individuals in settings appropriate to their needs and in a cost-effective manner."

Thousands of Louisiana residents with mental illnesses are being unnecessarily housed in nur…

The report focused on people with mental illness, but it broadly criticized the state for policies that led to an over-reliance on institutionalization.

Berger questions the veracity of the scathing report, in which some nursing home residents referred to themselves as "prisoners."

"I found it long on anecdotal interviews with severely mentally ill individuals and a little short on statistics," he said. "Not to say the interviews weren't valid, but it makes me wonder."

Wes Hataway, legal director for the nursing home association, said he doesn't believe the report showed Louisiana was violating federal law because it cited no specific instances of "unjustifiable institutionalization."

"That would mean a team of medical professionals has determined this person would be better served elsewhere, and I think if you go back and look at the report, it's short on any of those examples," Hataway said.

But state health officials say they understand they have a real problem on their hands.

"That is definitely a concern of mine, as you continue farther and farther down this path, sooner or later that is going to be an issue, and it's something the state needs to start proactively looking at," said Reynolds, the health undersecretary. "We have to invest in home- and community-based programs and get their rates up. It's going to take an investment."

Part 3 ... Profits over Patients: Louisiana Ignores Reform that Could Help Fix Budget Mess