KANSAS CITY, Mo. — Today marks a dark day in Kansas City history. 85 years ago mobsters gunned down and killed four law enforcement officers and a criminal fugitive at Union Station railroad depot. It was the morning of June 17, 1933.

The killings of four peace officers and the prisoner has gone down in history as the “Kansas City Massacre.” The mass shooting led to a major FBI policy change: agents began carrying firearms.

Back then a new house cost around $5,750. A loaf of bread cost 7 cents. Construction of the San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge started in January. The prohibition era would officially end by December. Gangsters, including Al Capone, controlled speakeasies and bootlegging operations, making millions in underground operations. Physicist Albert Einstein renounced his German citizenship that year and moved to the United States to become a professor of theoretical physics at Princeton. The world was on the brink of major changes, with Adolf Hitler appointed as Chancellor of Germany in January and Franklin D. Roosevelt inaugurated as the president of the United States in March.

The Kansas City Massacre started with an attempt by a gang led by Vernon Miller to free Frank “Jelly” Nash, a federal prisoner with a crime history spanning decades. On that dark day, Nash was in custody and was being returned to the U.S. Penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kansas. Nash had escaped from prison three years earlier.

Frank “Nelly” Nash

Nash is thought to have participated in some 200 bank robberies. He was born on February 6, 1887 in Birdseye, Indiana. His father, John “Pappy” Nash, started hotels in several southern towns – giving Nash multiple stomping grounds. Nash’s mother, Alta, was John’s second wife. Nash had two sisters and two stepbrothers. After living in dozens of places across several states, Nash treated Hobart, Oklahoma as his hometown.

Several mobsters considered Nash as a mastermind. He had connections with gangs across America. Past documents describe him as charismatic, friendly, likeable, and charming. His nickname, “Jelly” was shortened from “Jellybean.” He earned the name in childhood for his poise and well-groomed appearance. He was a career criminal who knew how to get what he wanted out of people, whether the law or fellow criminals.

Back in 1913, Nash and a friend, Nollie “Humpy” Wortman stole nearly $1,000 from a store in Sapulpa, Oklahoma. Adjusted for inflation, that would be over $18 thousand dollars today. While on the run, Nash told Wortman they needed to hide the evidence fast. As Wortman went to bury the wealth, Nash betrayed him and shot him in the back.

Police arrested Nash hours later. The court found him guilty of murder and sentenced him to life in the Oklahoma State Penitentiary. Five years later, Nash found a way to reduce his sentence to ten years. He convinced the warden he would join the army and fight in World War I. His life of crime didn’t stop there.

After years of going in and out of prison, he landed in the United States Penitentiary, Leavenworth in Kansas along with three members of the Spencer Gang. They received a 25 year sentence for mail robbery and assaulting a mail custodian. That was in March 1924. In 1930, Nash was appointed the deputy warden’s chef and general handyman; the jobs came with special privileges. He escaped on October 19, 1930, when he left the prison on an errand and never returned.

The FBI launched an aggressive search for Nash throughout the United States and most of Canada. The FBI discovered Nash assisted in the escape of seven prisoners from the United States Penitentiary, Leavenworth, on December 11, 1931.

FBI agents also found out that Nash had close friendships with Francis L. Keating, Thomas Holden, and several other gunmen involved in Midwest bank robberies. The more the FBI uncovered Nash’s underground connections, the more they wanted him in their custody.

FBI agents captured Keating and Holden on July 7, 1932 in Kansas City, Missouri. The pair told agents Nash was hiding out in Hot Springs, Arkansas, a hotbed of gangster activity. Illegal gambling spread like wildfire in Hot Springs following the Civil War, with two main factions: the Flynns and the Dorans. They fought one another throughout the 1880s for control of the central Arkansas town.

By 1933, the Arkansas city was considered a national gambling mecca, led by Owney Madden and his Hotel Arkansas casino. From 1927-1947, gambling and debauchery reached a pinnacle: there were ten major casinos and numerous smaller house spinoffs. It was the largest operation of its kind in the United States at the time. Hotels advertised rooms for prostitutes and off-track booking for horse races. At the time, it seemed like nothing could stop the operation; a former sheriff attempted to have Arkansas’ anti-gambling laws enforced and to secure honest elections — he was murdered in 1937.

Law enforcement apprehended Frank “Jelly” Nash at a Hot Springs store on June 16, 1933. FBI agents Joe Lackey and Frank Smith accompanied with Otto Reed, the Police Chief of McAlester, Oklahoma drove Nash north to Fort Smith, Arkansas. All four would board a train for Kansas City that night.

The Missouri Pacific train’s ETA was 7:15a.m. the following day. The lawmen made arrangements to meet at Union Station with Reed E. Vetterli, the special agent in charge of the FBI’s Kansas City Office.

Outlaws Plan Scheme

Word spread fast of the capture, and outlaws were upset one of their most dangerous masterminds had been captured. Out of allegiance to him, Nash’s cronies figured out the time he would arrive in Kansas City. They planned to liberate him, but Nash would be killed in the massacre.

Vernon Miller was the scheme ringleader. He served in the U.S. Army during World War I and was an experienced machine gunner. When he returned from the war, he went to his hometown Huron, South Dakota where he was elected as a policeman in 1920. Two years later, he was elected sheriff and was re-nominated for the position. But he got bored of serving. He disappeared before the election – and quickly became baptized into a life of crime.

In 1931, Miller moved to St. Paul, Minnesota and Chicago where he proved himself as a gunner and began associating with gangs.

Before the night of the Kansas City Massacre, Miller used a phone at Mulloy’s Tavern, a historic mob location in KC, to plan out his scheme to free Nash.

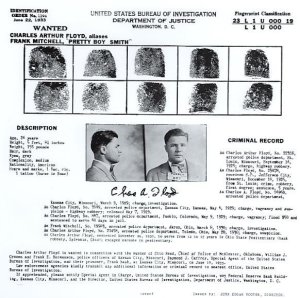

FBI reports find Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd and his sidekick, Adam Richetti, arrived in Kansas City to aid in the mission. Their travels to the city were anything but smooth. The pair had been detained in Bolivar, Missouri on the morning of the 16th. They needed car repairs, and while waiting at a local garage, Sheriff Jack Killingsworth appeared. Richetti recognized the sheriff and mugged him, seizing a machine gun. Richetti and Floyd held the sheriff and garage attendants at gunpoint. On the criminals’ orders, no one moved.

Floyd and Richetti then transferred their arsenal into another vehicle and ordered the sheriff to enter that vehicle, taking him as a hostage.

The two, along with their prisoner, drove north to Deepwater, Missouri. The cronies abandoned the stolen automobile and stole a new one. (Deepwater is about 85 miles southeast of Kansas City.)

After releasing the sheriff, Floyd and Richetti arrived in Kansas City about 10:00 p.m. on June 16.

That night Floyd and Richetti rolled their dice yet again and abandoned their automobile and stole another vehicle. Later they met Miller and went to his home… to be briefed on the mission and drink some beer.

Early the next morning, according to the FBI account, Miller, Floyd, and Richetti drove to Union Station in a Chevrolet Sedan. There they waited for Nash and his captors to arrive – and 30 pivotal seconds would go down in history.

Kansas City Massacre

Upon the arrival of the train in Kansas City, Agent Joseph Lackey went to the loading platform, leaving behind FBI Agent Frank Smith, Oklahoma Police Chief Otto Reed, and Frank “Jelly” Nash in a train stateroom.

On the platform, Lackey was met by Special Agent in Charge Reed Vetterli, FBI Agent Raymond J. Caffrey, and detectives W. J. Grooms and Frank Hermanson of the Kansas City Police Department. The lawmen surveyed Union Station and saw nothing suspicious.

SAC Vetterli told Agent Lackey that he and Agent Caffrey had brought two cars to Union Station for taking Nash back to the prison in Leavenworth.

Agent Lackey then returned to the train accompanied by Chief Reed, SAC Vetterli, Agents Caffrey and Smith, and Officers Hermanson and Grooms. They proceeded from the train through the Union Station lobby.

Both Agent Lackey and Chief Reed carried shotguns with them. Other officers carried pistols. SAC Vetterli is said to have been unarmed. Frank Nash, while in handcuffs, walked through Union Station with seven lawmen.

After leaving Union Station, the team with their captive paused briefly to survey the area a second time. Again, they saw nothing unusual.

Mass Shooting

Agent Caffrey unlocked his Chevrolet’s right door. When the door opened, Nash started to get into the back seat, but Agent Lackey told Nash to get into the front. The vehicle was a two-door sedan, and entering the back seat required pushing the back of the front seat forward.

Agent Lackey climbed into the back directly behind the driver’s seat. Agent Smith sat beside him in the center, and Chief Reed sat beside Smith… and behind Nash.

Agent Caffrey walked around the car to the driver’s seat on the left side. SAC Vetterli stood with Officers Hermanson and Grooms at the right side near the front of the car.

A green Plymouth was parked about six feet away. Agent Lackey saw two armed men run from behind it. At least one of them carried a machine gun.

From a distance approximately 15 feet diagonally to the right of Agent Caffrey’s Chevrolet, an individual crouched behind a car’s radiator and fired the machine gun.

Kansas City Police Officers Grooms and Hermanson died in the blast instantly. SAC Vetterli, who was standing beside Officers Grooms and Hermanson, was shot in the left arm. He dropped to the ground and attempted to scramble to the left side of the car to join Agent Caffrey — who had not entered the Chevrolet to sit in the driver’s seat.

When Vetterli turned a corner — he saw Agent Caffrey collapse. He died from a head wound.

Inside the car, the blast killed convict Frank Nash and Police Chief Reed. Agents Lackey and Smith survived the massacre by falling forward in the back seat. Lackey was struck and seriously wounded by three bullets. Smith survived the whole massacre without a scratch.

The three gunmen ran to the car they just targeted to look inside it; then they decided to flee the area. A Kansas City policeman emerged from Union Station and fired in the direction of one of the killers, later identified as Floyd, who slumped, but continued to run.

The killers entered a car and went westward out of the parking area and disappeared.

The three survivors, Agents Smith and Lackey and SAC Vetterli, reported that the attack lasted all of 30 seconds.

From their account, the two Kansas City police officers were killed immediately, followed seconds later by Frank Nash and Chief Reed and then by Agent Caffrey – he was transported to a hospital and was pronounced dead on arrival.

Timeline of the Aftermath

The mass shooting sent shockwaves throughout the public. Historians have said the attack highlights the lawlessness of Kansas City under the Pendergast Machine. Thomas Joseph Pendergast was an American political boss who controlled Kansas City and Jackson County, Missouri from 1925 to 1939. He used a large network of family and friends (along with some voter fraud) to elect politicians. The Pendergast Machine helped launch the political career of former president Harry S. Truman.

Following the Kansas City Massacre, the FBI found fingerprint impressions on beer bottles in Miller’s Kansas City home. The evidence helped the FBI identify those involved.

Death of Vernon Miller

On November 29, 1933 the FBI found Miller’s mutilated body in a ditch just outside Detroit, Michigan. The FBI concluded Miller had a fight with henchman Longie Zwillman, the head of a New Jersey mob. While in Newark, Miller had shot the henchman. Another of Zwillman’s associates killed Miller in retaliation.

Several authors, including Jay Robert Nash, have used Miller’s death to argue that the Kansas City Massacre wasn’t about a potential rescue. It could have been a syndicate hit meant to silence Nash since he had extensive understanding of the crime underworld and a long list of contacts.

Arrest of Adam Richetti

After escaping out of Kansas City, Floyd and Richetti made their way to Toledo, Ohio. They met two women there by the names Beulah — also known as Juanita – and Rose Baird. The four traveled north to Buffalo, New York. With alias names, the four of them rented a Buffalo apartment. Those living in the apartment reported the two couples seldom left home and usually only left for grocery trips. Witnesses report the women occasionally threw money out the apartment windows and offered candy to children playing in the streets.

The four, in a new Ford Sedan bought by Rose Baird, began a trip on October 20, 1934 to travel west.

Later that same day, Floyd crashed the vehicle into a telephone pole in Toldeo, Ohio. Police Chief J. H. Fultz went out to investigate – and a shootout escalated. Chief Fultz took Richetti into custody. Floyd escaped.

Richetti was indicted by the Jackson County Grand Jury on four counts of murder. He was found guilty on June 17, 1935, exactly two years after the deadly incident. Richetti appealed the conviction. The State of Missouri Supreme Court affirmed it on May 3, 1938.

As a final act to save him, Richetti’s lawyers argued he was insane, but this effort failed.

He was executed by gas chamber on October 7, 1938.

Death of Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd

Following the car crash in Toledo, Ohio the FBI and local police conducted a wide array of interviews and had an intensive search for Floyd in eastern Ohio. They found him hiding out in a farm outside Clarkson, Ohio on October 22, 1934. Floyd died in a shootout with police. Records show he died 15 minutes after he was shot.

Authorities found on Floyd a watch and fob, both with ten notches. Authorities in their report stated Floyd likely carved the notches to indicate how many people he had killed.

The four individuals who aided in the conspiracy—Richard Galatas, Herbert Farmer, “Doc” Louis Stacci, and Frank Mulloy—were indicted by a federal grand jury at Kansas City, Missouri, on October 24, 1934.

On January 4, 1935, the four were found guilty of conspiracy to cause the escape of a federal prisoner from the custody of the United States. On the following day, each was sentenced to serve two years in a Federal Penitentiary and pay a fine of $10,000 — the maximum penalty allowed by law at that time.

The Kansas City Massacre changed a major FBI policy. Prior to this event the agency did not have authority to carry firearms (although some agents reportedly did) and make arrests (they could make a citizen’s arrest, then call a U.S. Marshal or local law officer). A year later Congress gave the FBI statutory authority to carry guns and make arrests (in May and June 1934).

Sources:

For more information:

‘Pretty Boy’ Falls (2009 story)

FBI Case Records