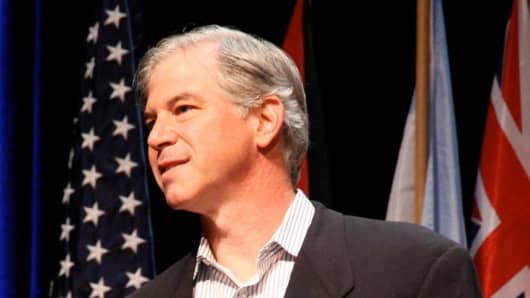

Former Enron Chief Financial Officer Andy Fastow—who developed many of the structured finance transactions that are often blamed for the energy giant's epic 2001 collapse—says the bankruptcy could have been avoided. And he says his one-time boss, former CEO Jeff Skilling—just re-sentenced to 14 years in prison—is not to blame for what was at the time the largest bankruptcy in U.S. history.

"Enron did not have to go bankrupt at the time that it did,"Fastow told an audience of around 2,500 at the annual conference of the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners in Las Vegas. Each year, the association invites a convicted white collar criminal to speak and offer insights.

Responding to a question from the moderator about Skilling's prison sentence, which a federal judge reduced Friday to 14 years from 24 years, Fastow said the lower sentence is nonetheless "significant" and"devastating."

While he declined to say whether Skilling deserves the punishment, Fastow said, "The decisions that made Enron go bankrupt were made after Skilling resigned."

Skilling resigned "for personal reasons" in August, 2001, after just six months as CEO. Fastow said the fateful decisions were made in October of that year. Enron, once the nation's seventh largest company, filed for bankruptcy on December 2, 2001.

Fastow himself served six years in prison after pleading guilty to reduced charges in exchange for his testimony against Skilling and Enron founder and Chairman Kenneth Lay at their 2006 trial. Skilling and Lay were not accused of causing Enron's bankruptcy. They were accused of conspiracy and securities fraud, so Fastow's assertions about who was or was not to blame did not come up in the trial.

Still, Fastow's conciliatory comments about Skilling were greeted angrily by Skilling defense attorney Daniel Petrocelli.

"Perhaps the number one reason Jeff was wrongly convicted and received that devastating sentence was because Fastow agreed to lie about Jeff to reduce his own sentence," Petrocelli said in an e-mail.

(Read More: The Truth About Why Jeff Skilling's Jail Sentence Got Downsized)

At the trial, Fastow testified he and Skilling had entered into secret side deals to move troubled assets off of Enron's books, which Skilling denied. A jury convicted Skilling on 19 criminal counts. Lay was convicted as well, but he died before he could appeal, so his case was thrown out.

In his speech on Wednesday, Fastow said all of the deals he worked on were blessed by attorneys and accountants, though he now realizes the transactions were misleading and fraudulent.

"My role was engaging structured finance transactions that made Enron look healthy when it was not," he said.

But he said those transactions did not cause Enron to go bankrupt. He would not elaborate on which decisions in October, 2001 were to blame for the collapse.