Shale binge has spoiled US reserves, top investor warns

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

A fracking binge in the American shale industry has permanently damaged the country’s oil and gas reserves, threatening hopes for a production recovery and US energy independence, according to one of the sector’s top investors.

Wil VanLoh, chief executive of Quantum Energy Partners, a private equity firm that through its portfolio companies is the biggest US driller after ExxonMobil, said too much fracking had “sterilised a lot of the reservoir in North America”.

“That’s the dirty secret about shale,” Mr VanLoh told the Financial Times, noting wells had often been drilled too closely to one another. “What we’ve done for the last five years is we’ve drilled the heart out of the watermelon.”

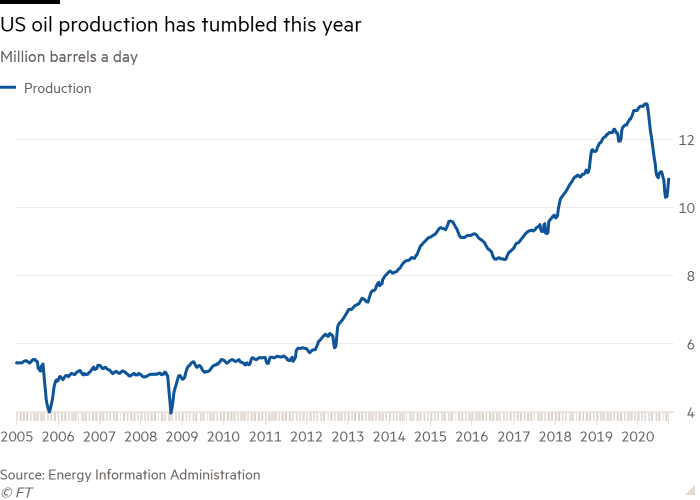

Soaring shale production in recent years took US crude output to 13m barrels a day this year and brought a rise in oil exports, allowing President Donald Trump to proclaim an era of “American energy dominance”.

Total US oil reserves have more than doubled since the start of the century as hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, and horizontal drilling unleashed reserves previously considered out of reach.

But the pandemic-induced crash, which sent US crude prices to less than zero in April, has devastated a shale patch that was already out of favour with Wall Street for its failure to generate profits, even while it made the country the world’s biggest oil and gas producer.

The number of operating rigs has collapsed by more than 60 per cent since the start of the year. US output is now about 11m barrels a day, according to the US Energy Information Administration, or 15 per cent less than the peak.

“Even if we wanted to, I don’t think we could get much above 13m” barrels a day, Mr VanLoh said. “I don’t think it’s physically possible, because we’ve messed up so much reservoir. I would argue that what the US was touting three or four years ago, in theoretical deliverability, is nowhere close to what we think it is now.”

He said operators had carried out “massive fracks” that created “artificial, permanent porosity”, inadvertently reducing the pressure in reservoirs and therefore the available oil.

The comments will cause alarm in the shale patch, given the crucial role of investors such as QEP in financing the onshore American oil business.

The Houston-based investor has assets under management of about $11.2bn, according to data provider PitchBook, and is one of the few private equity groups still focused on shale.

Twice weekly newsletter

Energy is the world’s indispensable business and Energy Source is its newsletter. Every Tuesday and Thursday, direct to your inbox, Energy Source brings you essential news, forward-thinking analysis and insider intelligence. Sign up here.

Private companies account for about 30 per cent of US oil production excluding Alaska and Hawaii, or about 2.7m b/d, according to consultancy Rystad Energy.

Other private equity investors have warned that the shale growth story has ended, despite an oil-price recovery in recent months to about $40 a barrel.

“They were making lousy returns at $65 a barrel,” said Adam Waterous, head of Waterous Energy Fund. “You need at least north of $70 before you start achieving a cost-of-capital return in the US oil business.”

Production from the Permian, the prolific shale field of west Texas and New Mexico, peaked even before the crash this year, Mr Waterous said. At current prices, only 25 per cent of US shale was economical, he added.

Analysts also say US oil output will struggle to recover its previous heights. Artem Abramov, head of shale research at Rystad, said production would remain between 11.5m b/d and 12m b/d at $40 a barrel. S&P Global Platts forecasts a decline to 10m b/d by mid-2021.

But the crash could create opportunities for QEP in the short term, Mr VanLoh said, especially if prices recovered.

While listed producers had mostly sworn off production growth, some QEP-backed companies, such as DoublePoint Energy — which played host to Mr Trump during the president’s July fundraising visit to Midland, Texas — were increasing drilling activity. It says its Permian acreage can still be profitable at current prices.

QEP’s portfolio companies would increase output this year by about 25 per cent, to 500,000 barrels of oil and gas a day, Mr VanLoh said.

“The next five years may be the best five years we’ve ever had for hydrocarbon investing,” he said.

But he is also adjusting his company’s strategy to reflect investors’ growing disquiet with fossil fuels. QEP’s new 10-year fund, VIII, would be launched in early November, he said, with $1bn of about $5.6bn of total capital commitment reserved for “energy transition” investments.

The company would soon appoint someone from outside the oil industry to enforce better environment, social and governance performance at QEP’s companies, Mr VanLoh added.

He said they would have to improve ESG “because ultimately you’re not going to get capital from us if you don’t . . . And we won’t be able to get capital from our limited partners if you don’t.”

A more efficient US shale sector would re-emerge from the crash, Mr VanLoh said, but it would be smaller and require a reduced workforce. He is now advising his friends’ children not to pursue a career in oil.

“I tell all of them — honestly, it’s a very risky bet and, if I were you, I would not go into it today.”

Comments