Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s[1] posthumously published work Letters and Papers from Prison receives mixed reviews from various quarters, including Evangelical Christians. I do not think it is only ‘death-of-God’ interpretive moves by liberals like Bishop John A.T. Robinson, William Hamilton, Thomas J.J. Altizer and others, or his associations with neo-orthodox and liberal theological figures,[2] that lead to Evangelical wariness in many quarters. Given our particular theo-political imagination and Weltanschauung,[3] we also struggle with Bonhoeffer’s affirmation of the Christian God as weak, secular man or man come of age as no longer needing religion, religionless Christianity, Jesus as the man for others, and the church as a community for others. However, these emphases are not incidental to Bonhoeffer’s later thought, but envisioned as indelible to his future work; those who would seek to give a full and faithful assessment of Bonhoeffer must account for them.[4] Further to the points above on conservative Evangelical moral intuitions, our movement favors patriotism and nationalism. Generally speaking, American Christianity affirms strength and power politically and economically. Evangelicals also affirm a form of reason that is powerful.

How does all this bear on the subject at hand? Having experienced marginalization in political and academic centers of power for a generation following the Scopes Trial, why would we wish to affirm Bonhoeffer’s Letters and Papers from Prison where only a suffering God can help us, and where we don’t seek to take back America, or Germany, but must lay down our lives for the other? American Evangelicalism, like much of American theology, is in various ways still engaging in God of the gaps theology and practice, whereas Bonhoeffer would call us to a God in the gallows theology and practice that leads us to care for the marginalized. Such a theology challenges the dominant worldview or Weltanschauung orientation that reflects a theology from above rather than from below, and which has often served empire building.[5]

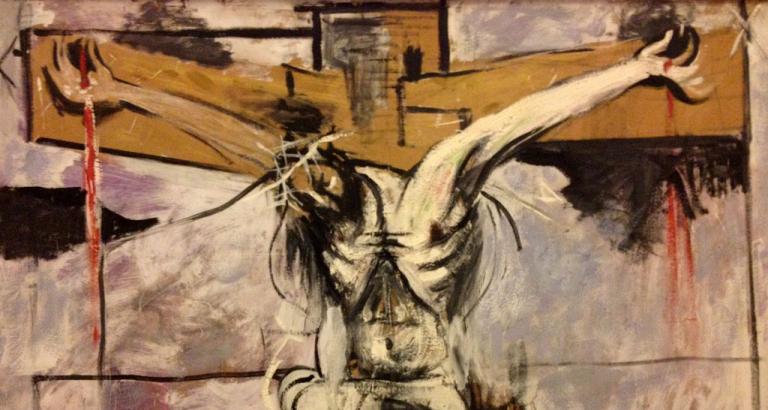

Whereas Eric Metaxas would take Bonhoeffer’s rejection of privatized religion to foster a public, “muscular Christianity” that features beating secularism in the public square (a popular view among many Evangelicals),[6] I take Bonhoeffer’s rejection of privatized religion to foster a public, suffering Christianity that moves us from the God of the gaps to God hanging in public on the lynching tree.[7] Bonhoeffer goes even further than Karl Barth here, for it is not simply God’s humanity,[8] but the God man, who suffers ridicule and shame. Unlike the long departed “undialectical shallow modernism” of the death-of-God theology that Eberhard Bethge dismissed in its heyday (but that Metaxas recently resurrects from the dead to beat its dead corpse and rebury[9]), this framework does not dismiss, discount and replace God’s deity, the church and its liturgy in favor of a Feuerbachian projectionist alternative. How can it, when in contrast to Ludwig Feuerbach, who projects our aspirations for infinitude onto the metaphysical void, the infinite God descends to be divine only in union with human finitude as the God-Man Jesus Christ for Bonhoeffer? Bonhoeffer’s Christology fully embodies God without remainder, unlike the logos asarkos and extra-Calvinisticum Christology and spirituality that continues to lay dormant existentially, culturally and politically in so many Christian circles.

As Bonhoeffer writes in Ethics, “The original and essential encounter with the human being and with God takes place in Jesus Christ. From now on it is no longer possible to conceive and understand humanity other than in Jesus Christ, nor God other than in the human form of Jesus Christ.[10]” Rather than allow Friedrich Nietzsche’s Übermensch as framed by Aryanism to plunder the temple treasury and ammunitions depot, removing the faith’s most potent jewels and weapons, Bonhoeffer holds tightly to the theology of the cross and brings it to bear in all its omnipotent weakness and omniscient foolishness in the public square of modern heathenism. This will move the church from a victimizing theology to one that takes sides with the victim, including the orphan, widow, and alien in their distress.

_____________________________________________

[1]This blog post is an edited selection of my paper, “Reimagining Piety, Prophetic Witness & Political Theology: An Appraisal of Bonhoeffer and Evangelicalism,” Evangelical Studies Unit, American Academy of Religion, Boston, MA, 2017.

[2]Stephen Haynes notes that the conservative Evangelical establishment takes issue with Bonhoeffer’s Letters and Papers due to its reception by the “Christian atheists.” Stephen R. Haynes’ assessment: “Between Fundamentalism and Secularism: The American Evangelical Love Affair with Dietrich Bonhoeffer,” in Dietrich Bonhoeffers Theologie heute: Ein Weg zwischen Fundamentalismus und Säkularismus? Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Theology Today: A Way between Fundamentalism and Secularism?, ed. John W. de Gruchy, Stephen Plant, and Christiane Tietz (Güterlsloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus, 2009), pages 220-221. In addition, some Evangelicals take issue with Bonhoeffer’s long-standing associations with neo-orthodox as well as liberal theological figures (See Haynes, pages 222-223).

[3]Works that are important to consider in attending to this theo-political worldview are Mark A. Noll, America’s God: From Jonathan Edwards to Abraham Lincoln (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005) and Molly Worthen, Apostles of Reason: The Crisis of Authority in American Evangelicalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016). Noll focuses a great deal of attention on the connection between Evangelicalism and American politics in America’s God, which is a socio-theological history of the U.S. One also needs to consider the predominant emphasis on Christianity as a worldview that comes with the resurgence of Calvinism in the United States (Kuyper and Dooyewerd were some of the first to champion Christianity as a Weltanschauung) and its popularization in the work of Evangelical leader Francis Schaefer. Such emphases stand in stark contrast to “religionless Christianity.” Here’s a key quote from Worthen’s volume: “The neo-evangelicals were overfond of this word, Weltanschauung, and its English synonyms: worldview, world-and-life view. They intoned it like a ghostly incantation whenever they wrote of the decline of Christendom, the decoupling of faith and reason, and the needful pinprick of the gospel in every corner of thought and action. … Most neo-evangelicals did not acquire the word from reading Immanuel Kant or the other German philosophers who sharpened its meaning. They picked it up from the works of Reformed theologians versed in German theology, such as Dutch churchman and politician Abraham Kuyper and James Orr … Americans and readers across the Anglosphere encountered the word [weltanschauung] in regular reports of the Nazis’ subjugation of German churches in favor of their own neo-pagan rituals; the eradication of peoples who were out of step with this worldview of Aryan blood and power; and Nazi wedding ceremonies, Teutonic pastiches of torches, uniforms, peasant costumes, crowns of flowers and greenery in which the officiant pronounced each couple ‘united in the Nazi Weltanschauung.’ … The rise of Nazism prodded some Westerners to realize that the conflict required not only manpower and material, but a coherent intellectual front as well. Hitler mocked the West’s insufficient ideology, contending in his speeches that ‘democracies like Britain, France, and the United States are inherently weak through lack of a Weltanschauung or definitive ideological content essential to their firmer consolidation.’ The Allies extinguished Nazism in 1945, but the victory inaugurated the West’s long war of ideology against the Soviet Union and other communist states. Marxism-Leninism and Maoism proved to be highly sophisticated world-and-life views, each a pseudo-religion and complete with its own sacred texts, rituals, plans of salvation, and transcendent meaning. … Now the way to understand one’s enemy was to see beyond his rhetoric, decipher his Weltanschauung— and defend one’s own.” Worthen, Apostles of Reason, pages 27-28.

[4]The following references and quotations are taken from Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Letters and Papers from Prison, edited by John W. de Gruchy, translated by Isabel Best, Lisa E. Dahill, Reinhard Krauss, Nancy Lukens, H. Martin Rumscheidt, and Douglas W. Stott (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2010):

On God’s weakness, see page 479: “The same God who is with us is the God who forsakes us (Mark 15:34!). The same God who makes us to live in the world without the working hypothesis of God is the God before whom we stand continually. Before God, and with God, we live with God. God consents to be pushed out of the world and onto the cross: God is weak and powerless in the world and in precisely this way, and only so, is at our side and helps us. Matt 8:17 makes it quite clear that Christ helps us not by virtue of his omnipotence but rather by virtue of his weakness and suffering!”

On “religionless Christianity,” see pages 362-364. Page 367 is on God addressing us not in our weakness but in our strength. Page 374 includes reflections on religionlessness in dialogue with Bultmann. Page 444 references the subject again in the context of a letter from Bethge.

On God of the gaps and the deus ex machina, see pages 366 and 450:

Page 366: “Religious people speak of God at a point where human knowledge is at an end (or sometimes when they’re too lazy to think further), or when human strength fails. Actually, it’s a deus ex machina that they’re always bringing on the scene, either to appear to solve insoluble problems or to provide strength when human power fails, thus always exploiting human weakness or human limitations. Inevitably that lasts only until human beings become powerful enough to push the boundaries a bit further and God is no longer needed as deus ex machina.”

Page 450: “Now I’ll try to continue with the theological topics from where I stopped recently. My starting point was that God is being increasingly pushed out of a world come of age, from the realm of our knowledge and life and, since Kant, has only occupied the ground beyond the world of experience. On the one hand, theology has resisted this development with apologetics and taken up arms—in vain—against Darwinism and so on; on the other hand, it has resigned itself to the way things have gone and allowed God to function only as deus ex machina in the so-called ultimate questions, that is, God becomes the answer to life’s questions, a solution to life’s needs and conflicts.”

On Jesus as the man for others, see page 501: “Encounter with Jesus Christ. Experience that here there is a reversal of human existence, in the very fact that Jesus only ‘is there for others.’ Jesus’s “being-for-others” is the experience of transcendence!”

On the church as a community for others, see page 503: “The church is church only when it is there for others. As first step it must give away all its property to those in need.”

On his outline for a book, see page 500, where he states that he would like his first chapter to be on religionless Christianity/a world come of age. His outline of the book, he writes, would only be 100 pages. Chapter one would be on “religionless Christianity/a world come of age” (page 500). Chapter two would be on “worldliness and God” (page 501 and following). Chapter three would be the “Conclusion” (page 503). Bonhoeffer refers to this work as a prologue to his Ethics, not an outline of it. A prologue to his Ethics connects it to Ethics as a precursor. By making this point, it suggests that Letters and Papers from Prison is not a fresh break representing a new direction in Bonhoeffer’s thought as many would like to suggest. On the relation of Letters and Papers to his envisioned Ethics, see page 518: “You ask how the shorter [“Outline for a Book” in Letters and Papers from Prison] and the large work [Ethics] fit together. I guess the best way to describe them is that the shorter piece is in a certain sense a prologue to the larger work and, in part, anticipates it.”

[5]Refer back to the footnote featuring Weltanschauung in Molly Worthen’s Apostles of Reason, pages 27-28.

[6]See for example Eric Metaxas, Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2010), page 467. Kate Bachelder refers to Metaxas’s brand of Christianity as “muscular” in her Wall Street Journal article: “The Death of God Is Greatly Exaggerated: The happy warrior for a muscular Christianity on why faith and science are not opposed, and why the public square benefits from expressions of belief,” in The Wall Street Journal, December 18, 2015. For critical reviews of Metaxas’s work, see the following: Clifford Green, “Hijacking Bonhoeffer,” The Christian Century, October 4th, 2010; Charles Marsh, “Eric Metaxas’ Bonhoeffer Delusions,” Religion and Politics, October 18th, 2016. Timothy Larsen also comments on how Metaxas’s biography “has skewed things in an evangelical direction.” See Timothy Larsen, “The Evangelical Reception of Dietrich Bonhoeffer,” in Keith L. Johnson and Timothy Larsen, eds., Bonhoeffer, Christ, and Culture, Wheaton Theology Conference Series (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Academic, 2013), page 50. For Larsen, such “skewing” is not necessary. Evangelicals should not force Bonhoeffer to fit their mold, admire what they appreciate, and thereby “provide valuable correctives that present a more accurate picture of a complex man and theological legacy” (page 51). Here is a direct quotation from Metaxas’s interview with Christianity Today, where he answers the question: “Would you describe Bonhoeffer as an evangelical?” Metaxas responds: “That is what’s so amazing. Bonhoeffer is more like a theologically conservative evangelical than anything else. He was as orthodox as Saint Paul or Isaiah, from his teen years all the way to his last day on earth. But it seems that theological liberals have somehow made Bonhoeffer in their own image, mainly based on the fact that he studied at Union Theological Seminary in New York, and that he wanted to visit Mahatma Gandhi, and that he used the phrase ‘religionless Christianity’ in a letter.” The quotation is taken from his interview with Collin Hansen, “The Authentic Bonhoeffer: Eric Metaxas explains how the German theologian lived a life worth examining,” in Christianity Today, July 1, 2010.

[7]For consideration of the political theological import of the lynching tree, see James H. Cone, The Cross and the Lynching Tree (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2011).

[8]See Karl Barth, “The Humanity of God,” in The Humanity of God (Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1960), page 46.

[9]Refer to page 466 of Metaxas’s Bonhoeffer biography, including the Bethge quotation. See also Green’s critique of Metaxas’s employment of the long-departed death-of-God movement in his Christian Century review, where the latter seems to suggest that the options are limited to a classic conservative-liberal binary in Bonhoeffer studies.

[10]Bonhoeffer, Ethics, page 253.