After more than a year of preparations, the exhibit was all set.

The Australian Embassy in DC had readied its gallery for the nine-week show, and artist Patricia Piccinini had selected the works she wanted displayed. But two weeks before it was to open, there was a problem. The Washington couple who owned the art was bickering over it.

“If we are no longer able to borrow the Piccinini exhibition for the upcoming show, then we need to know now,” Australia’s cultural attaché said in a frantic e-mail to a manager of the collection this past February. “Grateful for your urgent advice.”

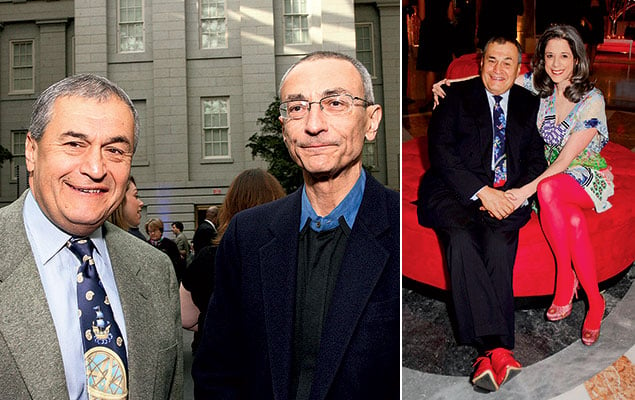

The husband and wife ultimately couldn’t agree to go ahead, according to court records, and the embassy had to cancel the show, making it unlikely collateral damage in the divorce of one of the country’s most powerful Democratic couples: superlobbyists Tony and Heather Podesta.

When they married 11 years ago, the Podestas were the talk of K Street. At 59, Tony was the brother of a former chief of staff to President Clinton, John Podesta, and a legendary political fixer who had turned a two-man lobbying shop into an industrial complex of influence peddling. Twenty-six years his junior, Heather was a 33-year-old congressional staffer, an up-and-comer with a law degree from the University of Virginia. Heather was his second marriage; he was her third.

Together, they blasted to the top of the Democratic food chain in a swirl of air kisses and PAC donations, handing out cash to liberal politicians including Hillary Clinton and Harry Reid and using their clout to help the world’s biggest companies—Walmart, BP, Toyota—advance their interests in Washington. Heather went on to found one of the US’s largest female-owned government-relations firms and become, as the Washington Post put it, “an It Girl in a new generation of young, highly connected, built-for-the-Obama-era lobbyists.”

While other liberals winced at the thought of trading high-minded ideals to shill for corporate America, the Podestas projected pride in their profession. They strutted through smoke-filled rooms with flash and flair—Tony in red Prada shoes, Heather in bright, eye-catching dresses—like public ambassadors for their often vilified industry.

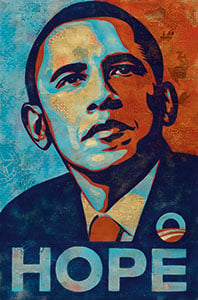

The partnership produced million-dollar returns, but never children. Instead, Tony and Heather Podesta had art. During their 11 years of marriage, the couple bought more than 700 contemporary artworks—sculptures by Louise Bourgeois, photographs by Katy Grannan, Shepard Fairey’s “Hope” portrait of Barack Obama—and built a collection of international acclaim. Then the relationship collapsed. And the Podestas found themselves in divorce court, fighting over one of the most lucrative brand names in DC politics, and all the spoils that came with it.

• • •

Art was the spark.

On their first date in 2001, Tony Podesta brought Heather Miller to his home to pick up his car before they headed to the opera. According to the Post, he walked past one of his sculptures and said, “I don’t know why it is, but I have artworks where the women have no heads.”

The following day, Heather wrote Tony a thank-you note and signed it, “Woman with a head.”

At the time they met, Heather was still grieving the collapse of her second marriage. A friend had thought she could use a blind date and set the college professor’s daughter up with the flamboyant lobbyist.

Over the previous 33 years, Tony had worked for six presidential candidates, from Eugene McCarthy to Bill Clinton. When Ted Kennedy’s campaign for the White House stalled in 1980, cash dried up and staffers were partly paid in donated art. Tony walked away from the campaign with his arms full of pieces by Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg. His interest in art collecting grew from there.

In 1987, Tony and his brother, John, launched their lobbying firm, known today as the Podesta Group, in the basement of a Capitol Hill rowhouse. Tony scrambled to turn almost two decades of Democratic contacts into clients and revenue. “Sometimes he had two phones going at once,” says John Raffetto, an early employee.

At night, Tony hosted fundraisers for leading Democrats at his home. Guests studied his art as they forked over campaign checks while Podesta’s mother, who had moved to Washington after her husband’s death, cooked her famous pesto sauce. These events—known as the Pesto PAC—could raise $50,000 in a single evening, allowing Tony to strengthen his ties to the Democratic luminaries he feted.

The family brand got the White House’s endorsement in 1993, when John Podesta left the firm to join Clinton’s staff, and with that, Podesta power stretched from K Street to the West Wing. While Tony has always insisted he never asks his brother for political favors, by 2001, the year Heather entered the picture, the Podesta Group was generating more than $7 million in annual lobbying revenue from clients like Philip Morris, Lockheed Martin, and Citigroup, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

Heather, meanwhile, talked up her man while working as an attorney for Congressman Robert Matsui, a California Democrat. “She was very quick to drop names, like ‘Oh, Tony and I saw Linda and Tom last night,’ ” says a former Matsui staffer who worked alongside her. “Of course, everybody knew it was Linda and Tom Daschle,” then the Democratic Senate minority leader and his wife.

Although capable and bright, Heather caused friction in Matsui’s office for appearing to want special treatment. Once, her supervisor let her take several days off in the middle of a congressional session, when the staff’s presence is most critical, because she insisted she had an important family event to attend in the States, according to the former colleague. Her supervisor soon learned that she’d been spotted at Dulles Airport waiting to board a flight to Italy, where Podesta owned a vacation home.

“It was very clear that she felt that she should be treated somewhat differently given who she was dating,” the former colleague says. (Through a spokesman, Heather Podesta declined to comment for this story.)

After dating for two years, Tony and Heather were married in April 2003, and Washington’s Democratic elite—House minority leader Nancy Pelosi, Vermont senator Patrick Leahy, New Mexico governor Bill Richardson—came out for the head-turning occasion. Heather recited her vows in a red silk dress, and popular local chefs Roberto Donna and Kaz Okochi catered the reception.

For a few months afterward, Heather continued to use her maiden name, as she had throughout her two earlier marriages. Tony warned her that if she took his name, people in Washington would identify her as either an ally or an enemy before even meeting her, National Journal reported. “That is so much cooler than being Heather Miller,” she said. “I’m ready to be a Podesta.”

• • •

The union was forged as Washington’s balance of power began to tilt in the Podestas’ favor. The Republican Revolution of 1994 had precipitated nearly a dozen straight years of conservative control of Congress, and throughout this time corporate America had relied primarily on GOP lobbyists to press their case in Washington. But the Iraq War helped turn Americans against Republicans; in 2006, voters installed Democratic majorities in the House and the Senate. Suddenly, private industry needed liberal allies on K Street—and nobody was better positioned than the Podestas.

In 2007, Heather decided to launch her own lobbying shop. She considered naming it Butterfly-Sting Strategies, according to the Wall Street Journal. Another option was Velvet Steel Strategies. Then the perfect name revealed itself: Heather Podesta + Partners.

In its first year, according to the Center for Responsive Politics, the firm took in $2.6 million from blue-chip clients like US Steel, HealthSouth Corp., and Boeing. “She’s never off duty on behalf of her clients,” says Eric Rosen, who was Heather’s second employee and still works at the firm.

The Podesta businesses were poised for even more growth in 2008 when Obama was elected President and Tony’s brother, John, stepped up to cochair the administration’s transition team. Heather and Tony emerged as one of Washington’s most conspicuous power couples. Each week, they sifted through dozens of invitations to determine which events were worth going to, according to a person familiar with their schedules, and arrived in colorful (un-Washington) outfits meant to spark conversations. (Heather once told the Post that she learned this trick by reading a networking manual.)

The couple spent $3.9 million to buy a home on Belmont Road in DC’s Kalorama and millions more to convert it into an art-filled Taj Mahal for their extravagant political fundraisers. They weren’t afraid to display some of their more provocative pieces; a nearly eight-foot-wide Sam Taylor-Wood photograph of a naked man, for instance, hung in the living room.

When they weren’t in Washington, Heather and Tony jetted off to their home in Australia or their apartment in Venice, sometimes meeting up with political heavyweights like Janet Napolitano and Ted Kennedy, according to the Post.

As Heather’s attorney would later put it, “they strategically cultivated their public image and worked to build the ‘Heather and Tony Podesta’ brand for the success of their shared enterprises.”

Their clients weren’t always the kind you’d advertise. Tony, for example, has represented the regime of Egyptian strongman Hosni Mubarak, now on trial for his role in the killing of more than 800 demonstrators during Egypt’s 2011 revolution. But there was never a trace of shame with the Podestas. At the Democrats’ 2008 convention in Denver, after Barack Obama assailed lobbyists as unduly influential, Heather and Tony wore lapel patches featuring a scarlet letter “L.”

The following year, Heather organized a fundraiser for California senator Dianne Feinstein and sent invitations promising “the Select Committee on Intelligence for the first course followed by your choice of Appropriations, Judiciary, or Rules committees,” according to Roll Call. Feinstein, who sits on each of these committees, heard about the invitation and canceled the event.

Ironically, the Obama administration’s ambitious first-term legislative agenda on health care, climate change, and financial reform created a bonanza for the very lobbyists the President wanted to freeze out. Between 2007 and 2012, revenue at Tony’s firm more than doubled, going from $11 million to $27.4 million, according to the Center for Responsive Politics; at Heather Podesta + Partners, revenue tripled to $7.9 million, a staggering increase from the $55,000 she was making the year she left the Hill.

The couple spent their cash on art-buying binges across the US and Europe, eventually amassing somewhere between 700 and 1,300 pieces of sculpture, paintings, photography, and video art that they loaned to museums including the National Gallery of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Guggenheim. They called it the Heather and Tony Podesta Collection.

• • •

Despite their hectic schedules, the Podestas appeared to be genuinely in love—so affectionate with each other that employees sometimes felt uncomfortable around them. “He has a pretty short fuse—he is very difficult to work for,” says a former senior Podesta Group staffer. “He’s a yeller, he’s a screamer—nasty e-mails 24-7. But with her, he was a complete freaking teddy bear. It was always better when she was around because he wasn’t such a jerk to deal with.”

Tony’s first marriage had ended bitterly, with his ex-wife claiming in court that when they split he undervalued his income by roughly half and, by doing so, reduced his child-support tab for their three adopted children. After 4½ years of litigation, Tony agreed to pay $265,000 to settle all financial obligations to his kids, who were adopted by his ex-wife’s new husband. (“He’s a great guy; I have nothing against him,” says one of those children, now 31.)

When Heather was around, Tony went from being an irascible boss to an entirely different person, and his affectionate behavior extended to business. If a conflict of interest with an existing client prevented him from taking on a new client, he often referred the customer to Heather, according to a current and a former senior staffer at Tony’s firm. (A person close to Heather says she referred even more business to Tony.)

Tony’s lobbyists also provided Heather with intelligence that helped her run her firm, the current and former staffers say. The ex-employee says he briefed Heather several times a year about developments on Capitol Hill, and the current staffer says Heather needed help understanding the administration’s approach to regulation. Providing such assistance to a competing lobbyist is unheard of on K Street. But “she was Tony’s wife,” the former staffer says, “so you kind of had to.”

• • •

Heather once told a Post style writer, “It takes a Podesta to take out a Podesta.” She was talking about the way she sometimes out-competed her husband for clients. But since the couple’s breakup, the line has taken on new meaning.

The romance had flamed out by early last year, when Heather left their Kalorama house for good and asked Tony for cash to put toward a $3.8-million property on nearby Wyoming Avenue, according to his court filings. Tony, still hoping to patch things up, paid half of the down payment.

But after she left, he heard rumors that Heather had a new boyfriend: Stephen Kessler, a Los Angeles filmmaker whose director credits include the 1997 slapstick comedy Vegas Vacation, starring Chevy Chase. Tony saw Heather and Kessler pictured together in magazines and learned they’d been spotted together at Washington events, according to someone close to Tony. “He felt hurt,” this person says. “He still cared about her.”

One day, Heather returned to the Belmont Road home and her house key wouldn’t work. Tony had changed the locks.

From there, the spat got petty. Tony later agreed to let her return to the house for a videotaped inventory of their belongings. But once inside, Heather went upstairs, “only to leave the videographer downstairs, lock herself in Mr. Podesta’s bedroom, and rummage through the safe and his suitcase,” Tony’s lawyer alleged in a court filing.

The day the couple filed for divorce this past April—Tony first, then Heather—details were leaked to the Post’s Reliable Source gossip column, where readers learned of Tony’s claim that Heather had changed the locks on the Venice apartment and, later, Heather’s allegation that Tony dated other people while she was with the Hollywood director (which Tony’s lawyer denies).

Because the Podestas didn’t have a prenuptial agreement, they turned to the go-to lawyers of Washington’s divorce bar in the fight over their loot. Tony hired Sanford Ain of Ain & Bank, who had helped billionaire Steven Rales of the Danaher Corporation unwind his marriage and BET cofounder Sheila Johnson hers. Heather enlisted three firms: Feldesman Tucker Leifer Fidell; Pasternak & Fidis; and Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom.

They agreed that a judge needed to divvy up the assets they had acquired together—jewelry, real estate, and Heather’s company (because she had started it after they married). But Heather also wanted a share of the value of Tony’s lobbying shop (which he said was off-limits because he’d started it before they married and which she said was fair game because he’d owned one firm before they wed but started his current firm afterward).

Then there was the art. Of everything they owned, it was their most valuable asset, amounting to nearly 50 percent of their estate, according to Heather’s court filings. She wanted half of it. Tony wanted a share equal to what he’d put in, which could give him more than half.

Local museums found themselves caught in the middle. After the couple separated, Heather ordered Tony not to unload their holdings. According to court filings, Tony responded by giving three photographs to the National Gallery of Art and 20 other works to the National Museum of Women in the Arts—where Heather is a trustee.

This past winter, Tony wanted to give some art to the Phillips Collection, but the museum refused to accept it after receiving a letter from Heather’s attorney warning that he didn’t have permission to do so. Tony donated the art to the National Gallery instead.

• • •

The case basically boiled down to the Podesta brand—who had built it and who owned it.

Tony insisted that he was responsible for Heather’s success, claiming that he taught her the business and introduced her to key contacts. “Ms. Podesta’s career has risen meteorically since the parties’ marriage,” he argued in court papers. She “used Mr. Podesta’s name and reputation to advance her own business and interests.”

Heather insisted that she’d taken Tony’s name “as a loving commitment” to him and that the couple had acted as a team, sharing ideas and connections that benefited both firms. Tony had once told her “she was one of the top three rainmakers for The Podesta Group (even though she also had her own firm and clients),” one of her court filings said.

“Together,” as Heather’s attorney put it, “the parties experienced growth in their businesses and in their income and assets that neither had experienced individually.”

Heather and Tony racked up 109 hours with a mediator—nicknamed “the closer” for her ability to engineer out-of-court settlements—but the $60,000 process wasn’t enough to end their war. So in early June, they made their first appearance in court. During the hearing, their lawyers made a point of staking their claims to the famous last name: Tony’s lawyer would refer to Heather only as “Ms. Miller Podesta.” Heather’s lawyer, meanwhile, called his client “Ms. Podesta.”

By then, as they say on K Street, the Podestas had lost control of the narrative.

So not even a week later, and staring down the possibility of an embarrassing public trial, Tony and Heather decided to do what was best for business: They reached a private settlement and immediately launched the kind of charm offensive they’d normally get to bill for, issuing statements of mutual admiration and respect, pledging to loan out their art together, and professing to be dear friends.

“In politics, the art world and in life, there is only one Tony Podesta,” she wrote. “It was a great joy to share my life with Heather Podesta,” he wrote.

Tony keeps his lobbying firm and Heather hers. Nobody needs new business cards—they both get the name.

Senior writer Luke Mullins can be reached at lmullins@washingtonian.com. This article appears in the August 2014 issue of Washingtonian.

![Luke 008[2]-1 - Washingtonian](https://www.washingtonian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Luke-0082-1-e1509126354184.jpg)