Here is how our chain began: In 1973, my uncle, the middle brother of six children, graduated from medical school in Dhaka and made up his mind to find a way to the United States.

Bangladesh, newly independent after a brutal liberation war with Pakistan — one in which Nixon had looked the other way as its Cold War ally slaughtered thousands of Bangladeshis — had suspended the qualifying medical exam for students to go abroad, in a feeble display of nationalism intended to prevent brain drain. It didn’t work — my enterprising uncle finagled a visa to England and stayed for six months, peeling potatoes and hauling sacks of rice at a London restaurant to support himself, while he studied for the test.

By 1976, he had made it to the promised land: a residency in Washington DC. Five years later, he petitioned for visas for two of his brothers — my youngest uncle and my dad.

My dad wore tight, tan bell-bottoms then, his moustache was fuller, and a tuft of hair fell stylishly over his forehead. He had been married less than a year, and he and my mom plotted their routes home so they could swing by the US Embassy in Dhaka once a month to see how far they had inched up in the immigration line for a fourth-preference family visa — the ones reserved for the siblings of US citizens.

They waited 10 years. When the letter finally arrived informing them that their number was up, I was a gap-toothed 5-year-old. I didn’t exactly know what America was or what all the fuss was about, but I knew MacGyver, the hero of my very favorite TV show, lived there, so I was game.

After the reams of paperwork had been submitted, the background checks passed, and the interviews conducted, after my uncle swore to the US government that he would be our financial support for our first, fragile years in our new country, we landed at JFK on June 13, 1993. The date is stamped in red right above where our visa designations are scrawled in permanent marker on now-defunct Bangladeshi passports: F42, brother or sister of US citizen who is at least 21 years of age. F42, spouse of F41. F43, child of F41. That’s me.

My uncle, by then a successful gastroenterologist, drove us from the airport to his sprawling house in the suburbs of Baltimore. Over the following months, he was the bestower of both soft and hard skills. He gave my dad driving lessons, introduced me to the wonder of Rice Krispies for breakfast, and generally served as a guru as my parents gingerly built the scaffolding for their unfamiliar new lives. He also took me to an Orioles game, where I had the quintessentially American experience of feeling bored by baseball and sick after eating a hot dog too fast.

In late summer, my mom, my dad, and I boarded a Greyhound bus bound for Dallas, where my dad had a job waiting, his pockets heavy with the phone numbers of other Bangladeshis in Texas who were now tasked with answering all of our burning questions.

What is the Super Bowl? Who are the Cowboys?

What makes a “good” Halloween costume?

What is the meaning of the phrase “scoot over”?

Over the last 40 years, the numbers of Khans in the US has only multiplied. There’s the three of us, my two uncles, my aunt, their spouses, and seven children, a mix of Bangladeshi- and American-born.

Donald Trump, and the immigration restrictionists who paved the path before him, surely see malice in this story, each arrival, pulled in and helped by the ones that came before, a new threat, a fresh pollutant. On Dec. 18, the official White House account tweeted a family tree–style graphic of faceless stick figures, with the text “It’s time to end Chain migration.” It’s a term that strips the sentimentality from the way the US has legally allowed in newcomers for generations — through family ties.

Trump believes so adamantly in cutting off this contagion that he is holding hostage negotiations over the legal status of almost 700,000 DACA recipients until he can make progress on this other front. His crusade was given an extra boost when, in early December, 27-year-old Akayed Ullah, a fellow F43 from Bangladesh, was accused of haphazardly trying to blow himself up at Port Authority, ultimately injuring no one except himself.

It should go without saying that there are hundreds of thousands of immigrants who come in through family visas who have never ever thought of perpetrating a terrorist attack, who were dismayed by Ullah’s boneheadedness, many of them New Yorkers who were also irate at the fact that he snarled train traffic during rush hour.

Some form of family reunification has been a tenet of our immigration laws since the 1920s, with the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, signed by Lyndon B. Johnson at the height of the civil rights movement, eliminating the old, often racist quota system based on nationality and codifying one that allowed entire families to slowly uproot themselves and move stateside. Once upon a time, this was considered a good thing. It remains the way that most people find a foothold here. Of the 1 million new green card holders in 2015, 64% were related to a US citizen or legal permanent resident, according to the Migration Policy Institute.

The thinking behind this kind of migration still holds: People may initially be drawn by a paycheck but they stay when they are allowed to build a community. In those harrowing first years, relatives and friends — many of them fellow immigrants from the same country of origin — are the ones who counsel and coach you, who bail you out should you ever find yourself in trouble, and who show you that it’s possible to endure, even to flourish. They are your safety net.

When the power was suddenly cut off in our Dallas apartment within a month of moving in, my parents took some comfort in knowing they had someone to call (they hadn’t known how to activate their account with the utility company). When my dad struggled to buy car insurance because he had no driving history in the US, it was a family friend that referred him to a Bangladeshi business for help.

Given Trump’s inclination toward a white nationalist state, I can see why the idea of enticing immigrants — especially people of color and the not-already-wealthy — to build long-term lives in the US is threatening. What irks me more is the number of people who seem to think a “merit-based” immigration system is obviously preferable, setting up a neat dichotomy between the deserving and undeserving. There are those who have earned the opportunity to step foot on our shores, those who will contribute (mostly people from Norway), and those who will drain the US of its resources and its purity (people from “shitholes”). It’s the same simplistic, sinister view of the world that divides it into “takers” and “makers,” as the acolytes of Ayn Rand, including House Speaker Paul Ryan, see it.

The truth is no matter the avenue, it takes real grit to make it in a country where access to health care is precarious, where one misfortune can easily knock out months of savings, where success is as unpredictable and sometimes as likely as a lightning strike — a product of hard, sometimes humiliating work, sheer force of will, and dumb luck. Yet immigrants and their children find a way to make something from nothing every single day.

In the schema preferred by the RAISE Act, a proposal endorsed by the White House, legal immigration would be cut in half and points would be awarded to prospective migrants on the basis of age, education, income, job prospects, and proficiency in English. The New York Times estimates that only about 2% of American citizens would muster the 30 points required to be considered for a green card. Of course, of course, immigrants would be required to be 50 times as good.

Logically, I know this is insanity. But lately I also find myself compelled to justify my family’s existence here, to myself and to others. Let me tell you about our impeccable credit scores, about the amount of property taxes we’ve paid between us, and the schools and roads that they’ve financed. Do you know how many degrees we’ve accumulated in our time here? The number of doctors and lawyers we produced (as well as one writer and late-night researcher)?

Our claim to this country now depends on our respectability, the careful cataloguing of our contributions and our hardships, instead of our humanity. If you’re Muslim like us, or brown like us, the accomplishments have to be all the more dazzling.

How many points, I wonder, could we be retroactively awarded for the number of grocery carts that my 100-pound mother hauled across the parking lot of an Albertsons, alongside teenagers working summer jobs, in the punishing Texas heat?

How many for the nights of sleep my dad lost when he tried to square the cost of my tuition with his salary as the manager of a Staples?

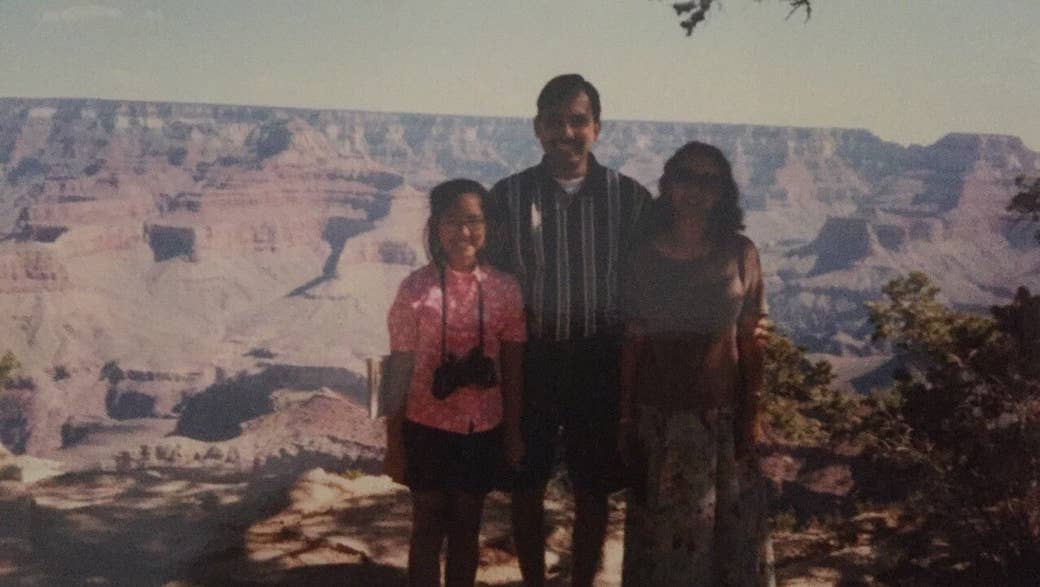

How many for the joy of our very first family vacation, when we loaded up our creaking station wagon and drove it to Galveston, for the sheer exhilaration of being able to afford a weekend away and dig our toes into the sand?

How many for our willingness to leave comfortable lives and start from scratch?

Have we earned our place? Has it been enough? ●

Naureen Khan is a writer and senior researcher at Full Frontal With Samantha Bee. She lives in Harlem.