On a recent Saturday morning, Craig Adams stood outside the Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital in New Brunswick, New Jersey. It was sunny but cold. Adams, who had turned 40 the day before, wore white sneakers and a black T-shirt over a long-sleeve shirt. A fuzz of thinning hair capped his still-youthful face. His appearance would have been unremarkable if not for the red splotch of fake blood on the crotch of his white trousers. The stain had the intended effect: drivers rounding the corner were slowing down just enough to see the sign he was holding, which read “No Medical Excuse for Genital Abuse.”

Next to him, Lauren Meyer, a 33-year-old mother of two boys, held another sign, a white poster adorned only with the words: “Don’t Cut His Penis." She had on a white hoodie with a big red heart and three red droplets and a pair of leopard-print slipper-boots to keep her feet warm for the several hours she would be outside. Meyer’s first son is circumcised; she sometimes refers to herself as a “regret mother” for having allowed the procedure to take place.

It was two days after Christmas. Adams and Meyer had each driven about an hour to stand by the side of a road holding up signs about penises. On that same day, a woman stood alone at what qualifies as a busy intersection in the small town of Show Low, Arizona. She also wore white trousers with a red crotch and held aloft anti-circumcision signs. A few more people did the same in the San Francisco Bay area.

The protests were triggered by a recent event, but the issue at stake was an ancient one. Circumcision has been practiced for millennia. Right now in America, it is so common that foreskins are somewhat rare and may become more so. A few weeks before the protests, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) had suggested that healthcare professionals talk to men and parents about the benefits of the procedure, which include protection from some sexually transmitted diseases, and the risks, which the CDC describes as low. But as the protesters wanted drivers to know, there is no medical consensus on this issue. Circumcision isn’t advised for health reasons in Europe, for instance, because the benefits remain unclear. Meanwhile, Western organizations are paying for the circumcision of millions of African men in an attempt to rein in HIV—a campaign that critics say is also based on questionable evidence.

Men have been circumcised for thousands of years, yet our thinking about the foreskin seems as muddled as ever. And a close examination of this muddle raises disturbing questions. Is this American exceptionalism justified? Should we really be funding mass circumcision in Africa? Or by removing the foreskins of men, boys, and newborns, are we actually committing a violation of human rights?

The history of this procedure

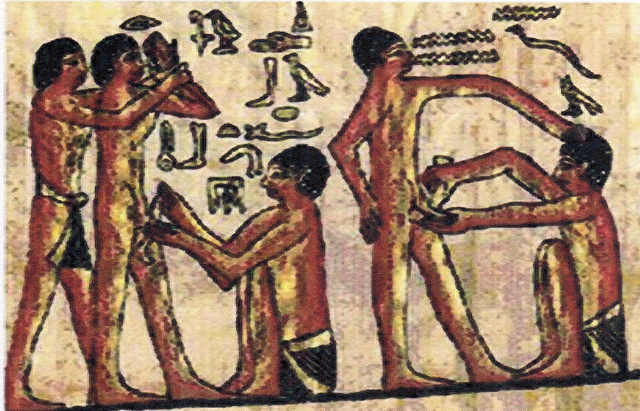

The tomb of Ankhmahor, a high-ranking official in ancient Egypt, is situated in a vast burial ground just outside Cairo. A picture of a man standing upright is carved into one of the walls. His hands are restrained, and another figure kneels in front of him, holding a tool to his penis. Though there is no definitive explanation of why circumcision began, many historians believe this relief, carved more than four thousand years ago, is the oldest known record of the procedure.

The best-known circumcision ritual, the Jewish ceremony of brit milah, is also thousands of years old. It survives to this day, as do others practiced by Muslims and some African tribes. But American attitudes to circumcision have a much more recent origin. As medical historian David Gollaher recounts in his book Circumcision: A History of the World’s Most Controversial Surgery, early Christian leaders abandoned the practice, realizing perhaps that their religion would be more attractive to converts if surgery wasn’t required. Circumcision disappeared from Christianity, and the secular Western cultures that descended from it, for almost two thousand years.

Then came the Victorians. One day in 1870, a New York orthopedic surgeon named Lewis Sayre was asked to examine a five-year-old boy suffering from paralysis of both legs. Sayre was the picture of a Victorian gentleman: three-piece suit, bow tie, mutton chops. He was also highly respected, a renowned physician at Bellevue Hospital, New York’s oldest public hospital, and a founder of the American Medical Association.

After the boy’s sore genitals were pointed out by his nanny, Sayre removed the foreskin. The boy recovered. Believing he was on to something big, Sayre conducted more procedures. His reputation was such that when he praised the benefits of circumcision—which he did in the Transactions of the American Medical Association and elsewhere until he died in 1900—surgeons elsewhere followed suit. Among other ailments, Sayre discussed patients whose foreskins were tightened and could not retract, a condition known as phimosis. Sayre declared that the condition caused a general state of nervous irritation, and circumcision was the cure.

His ideas found a receptive audience. To Victorian minds, many mental health issues originated with the sexual organs and masturbation. The connection had its roots in a widely read 18th-century treatise entitled Onania, or the Heinous Sin of Self-Pollution, and All Its Frightful Consequences, in Both Sexes, Considered. With Spiritual and Physical Advice to Those Who Have Already Injur’d Themselves By This Abominable Practice. The anonymous author warned that masturbation could cause epilepsy, infertility, “a wounded conscience,” and other problems. By 1765 the book was in its eightieth printing.

Later puritans took a similar view. Sylvester Graham associated any pleasure with immorality. He was a preacher, health reformer, and creator of the graham cracker. Masturbation turned one into “a confirmed and degraded idiot,” he declared in 1834. Men and women suffering from otherwise unlabeled psychiatric issues were diagnosed with masturbatory insanity; treatments included clitoridectomies for women, circumcision for men.

Graham’s views were later taken up by another eccentric but prominent thinker on health matters: John Harvey Kellogg, who promoted abstinence and advocated foreskin removal as a cure. (He also worked with his brother to invent the cornflake.) “The operation should be performed by a surgeon without administering anesthetic,” instructed Kellogg, “as the brief pain attending the operation will have a salutary effect upon the mind, especially if it be connected with the idea of punishment.”

Counter-examples to Sayre’s supposed breakthrough could be found in operating theaters across America. Attempts to cure children of paralysis failed. Men, one can assume, continued to masturbate. It mattered not. The circumcised penis came to be seen as more hygienic, and cleanliness was a sign of moral standards. An 1890 journal identified smegma as “infectious material.” A few years later, a book for mothers—Confidential Talks on Home and Child Life, by a member of the National Temperance Society—described the foreskin as a “mark of Satan.” Another author described parents who did not circumcise their sons at an early age as “almost criminally negligent.”

By now, the circumcision torch had passed from Sayre to Peter Charles Remondino, a popular San Diego physician descended from a line of doctors that stretched back to 14th-century Europe. In an influential 1891 book about circumcision, Remondino described the foreskin as a “malign influence” that could weaken a man “physically, mentally and morally; to land him, perchance, in jail or even in a lunatic asylum.” Insurance companies, he advised, should classify uncircumcised men as “hazardous risks.”

Further data came from studies of the “Hebrew penis,” which showed a “superior cleanliness” that had protective benefits, according to John Hutchinson, an influential surgeon at the Metropolitan Free Hospital of London. Hutchinson and others noted that Jews had lower rates of syphilis, cancer, and mental illness, greater longevity, and fewer stillbirths—all of which they attributed to circumcision. Remondino agreed, calling circumcision “the real cause of differences in longevity and faculty for enjoyment of life that the Hebrew enjoys.”

By the turn of the 20th century, the Victorian fear of masturbation had waned, but by then circumcision become a prudent precaution, and one increasingly implemented soon after birth. A desire to prevent phimosis, STDs, and cancer had turned the procedure into medical dogma. Antiseptic surgical practices had rendered it relatively safe, and anesthesia made it painless. Once a procedure for the relatively wealthy, circumcision had become mainstream. By 1940, around 70 percent of male babies in the United States were circumcised.

reader comments

850