Editor’s Note: Amanda Levete is a RIBA Stirling Prize-winning architect and founding principal of AL_A, an international award-winning design and architecture studio based in London. For her September 2017 CNN Style guest editorship, she explored the theme of thresholds – both real and imagined – as applied in architecture and far beyond.

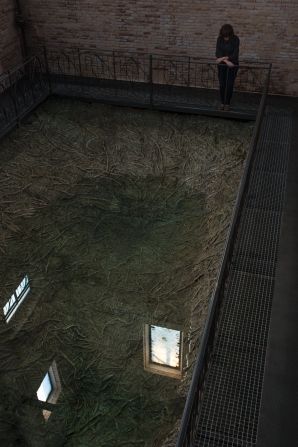

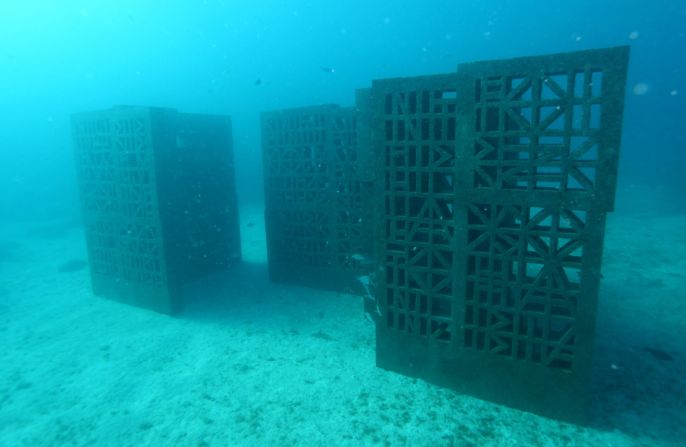

The Spanish artist, Cristina Iglesias creates extraordinary places of sanctuary and contemplation. And she’s done so thrillingly and inventively all over the world: inside and outside some of the great European and American museums, in the sea off the coast of Mexico, in a Brazilian botanical garden and, closer to home, inside a water tower and a convent in Toledo, Spain.

Iglesias’s avowed intention, she says, is “to change the rhythm” of our lives, make us pause and reflect. This is art that is intended to trigger memories and induce reverie.

Iglesias’ work defies easy definition as it straddles both sculpture and architecture. While she’s described as a visual artist, she is clearly frustrated by the term.

“I am,” she exclaims with a broad smile, “a constructor!”

And as such, she enjoys working with architects, most recently Norman Foster and Renzo Piano.

“They find me useful,” she says “(Architects) always have problems. We (artists) have a license to do things differently.”

A recurring theme in her work has been thresholds – entrances and exits, passageways and labyrinths. And she has increasingly begun to use moving water in her work. We enter a space, we pass through it, we stand still, we look around.

“An in-between is an important concept in my work,” Iglesias says. “You don’t know where the water comes from, where it goes. You’re at a threshold to an unknown space.”

We meet up at The Ned, a former 1920s bank in the heart of the City of London, freshly transformed into a hip heritage hotel and club. The place is noisily abuzz at lunchtime, thanks to the multiple restaurants across the open-plan ground floor. We can’t hear ourselves think. Without any obvious sanctuary, the concierge directs us towards the lifts. We eventually find an untended bar on the top floor and manage an hour or so of intense artistic conversation before we’re moved to make way for a party.

At 60, Cristina Iglesias is among Spain’s most well-established artists internationally, although poorly represented in Britain’s permanent collections. She was staying at The Ned as she completed a big commission for Bloomberg’s new European Headquarters, designed by Foster + Partners, just a short walk away. Iglesias’ participation was encouraged by Foster himself (they’ve been trying to work together for some years), and ultimately approved by the billionaire client, Michael Bloomberg.

Earlier this year, Iglesias made a piece named “The Ionosphere (A Place of Silent Storms)” for the Norman Foster Foundation in Madrid. A canopy of suspended lattice panels offering shelter and shadow in a courtyard, connecting one building to another, the work was yet another take on the threshold.

The Bloomberg piece is provisionally entitled “Forgotten Streams.” She showed me photos and apologized that she wasn’t able to take me to the site, which was still under wraps. All will be publicly revealed at the opening in October.

Iglesias is creating “a sort of river,” she says, which will appear to pass under the building and come out the other side. The project has been complex, requiring a team of hydraulic engineers and foundry workers. Iglesias talks of “cutting into the urban floor” of water moving slowly and vigorously, on the surface and underground. Her riverbed is composed of sheets of bronze in “patinated gold, black and oxidized green, yellow and blue,” she says. The sheets are imprinted with vegetable matter: roots, branches, leaves and other things, some recognizable, some not.

Iglesias made 1:100 scale models in her Madrid studio. The final effect promises to be both abstract and primordial. The water will ebb and flow; Iglesias says she wants to create “an activity, a whirlpool.” The two visible bodies of water – on either side of the building – will be substantial: a trapezoid measuring 27 by 7 meters (89 by 23 feet) and a distorted rectangle that’s 10 by 9 meters (33 by 30 feet). Iglesias and her engineers are refining the water flow – there are 40 or more hidden water sources.

Iglesias’s best-known artworks are probably the ones situated at museum entrances. “The Deep Fountain” (2006), which sits outside the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp in Belgium, is another flowing body of water: a rectangle measuring 37 meters by 17 (121 by 56 feet). Every hour or so, water emerges and drains into a long fissure, which bisects the piece. Many visitors are so enraptured that they just stop and watch the whole cycle. A team from Foster + Partners happened to see the fountain switched on in winter and were entranced to watch the ice crack and the water bubble up again. Norman Foster saw the video, which triggered the collaboration with Iglesias.

The Spanish word for threshold is “umbral,” Iglesias tells me. And her most literal expression of it is can be found at the entrance to the modern extension to Madrid’s Prado Museum, designed by the Spanish architect Rafael Moneo in 2007. Here, Iglesias created huge ceremonial doors. At 9 meters (30 feet) high, they dwarf every visitor. The great bronze doors are a mutable threshold between the city and its great arts temple. The doors automatically open and close at certain points throughout the day, at one point aligning to create a deep shadowy passageway. Entering it is liking stepping into some dark forbidding forest, which is perhaps precisely the right way to prepare for late Goya.

For the approach to Renzo Piano’s first Spanish project, the Centro Botín on the waterfront in Santander, Spain, which opened in June, Iglesias created a series of triangular wells and a sloping pool called “From the Underground.” Again, the water rises and recedes.

The great English art critic John Berger, who died earlier this year, reviewed her first British exhibition at London’s Whitechapel Gallery in 2003. He wrote in the Observer: “… her works beg for silence, because each piece is about listening - listening to a fugitive space or an arriving light … She is a silent singer who transports the listener to an elsewhere.”

Cristina Iglesias was generous with her time with me. She was excited by the Bloomberg piece. It was “still evolving as I make it,” she said, anxious that “it will work in the way I dreamt.”

She promised to show me around in October. I can’t wait.