"A box? Just for mail? Criminy."

Mule Mail: 19th Century to Present

Animals have always played a major role in delivery services—from the Pony Express to horse-drawn carriages—but only one beast is still hauling mail today. A handful of mules still pick their way through the Grand Canyon six days a week to deliver mail and other supplies (mostly food) to the residents of Supai, Arizona. (The only other ways to reach the town are by helicopter or by rafting down the Colorado River.) The journey takes about three hours on the way down, but up to five coming back up, even after the mules have shed loads of up to 200 pounds. The Supai route was first documented in photographs in 1938, but was already well-established at that point; today, it’s the last route being serviced by mule.

Nonstop Boat: 1873 to Present

Magnolia Springs, Alabama, has the only year-round water mail-delivery route in the U.S. The 31-mile-long route started back in 1915 and now services about 180 homes. (There are other water routes in the U.S., which operate on a seasonal basis.) Mailboxes are located on docks, and the delivery person drives a 15-foot Alumacraft boat that rarely comes to a complete stop.

One of those seasonal routes is Geneva Lake, Wisconsin, which employs an even more niche version of boat delivery: mail jumping, so named because the deliverer must jump off the boat onto a dock, swap incoming and outgoing mail, and jump back onto the still-moving boat. The system began in 1873, before roads had been built around the lake; these days, six jumpers are hired every year for summer delivery only.

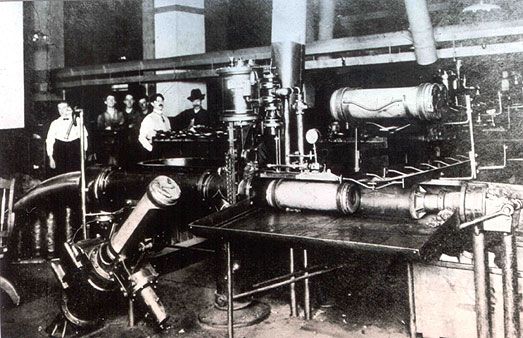

Pneumatic Mail Tubes: 1893 to 1953

New York, Boston, St. Louis, Chicago, and Philadelphia all used an underground system of pneumatic tubes to move mail during the early 20th century. The two-foot-long canisters held 600 letters as they moved through the tubes at an average speed of 35 mph. There were about 27 miles of pneumatic tubes running through New York City alone, including routes stretched across the Brooklyn Bridge that linked Manhattan with Brooklyn. New Yorkers, testing out the newfangled technology, sent through a Bible, a copy of the Constitution, and a cat (who emerged unharmed but presumably rattled). At its peak, nearly one third of New York mail traveled through the pneumatic system every day.

The service was suspended during WWI in an attempt to conserve funding for the war effort; after the war, only New York and Boston picked it back up again. The proliferation of delivery trucks and expanding urban centers contributed to the tubes’ demise. Private contractors leased the pneumatic tubes to the USPS, and by 1934, rates were as high as $19,000 per mile per year. Even though they’re no longer in use, many of the tubes remain intact under city streets today.

The Model-T Snowbird: 1921

Although this vehicle was never officially part of the USPS fleet, a handful of carriers relied on the Model-T Snowbird attachment kit to plod along snowy routes, providing an alternative to horse and sleigh. The truck had interchangeable skis and tank-like treads on the rear tires. Over 300,000 attachments were produced for rural delivery vehicles to use. Snowmobiles are still used in places like Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Alaska for winter deliveries.

Gyrocopters: 1939 to 1940s

The autogiro, a single-person helicopter-ish vehicle, was invented in the early 1920s by a Spanish engineer named Juan de law Cierva. The USPS decided to test out the contraption for mail-delivery purposes, and convinced Congress to fund experiments on autogiro mail delivery starting in 1937; the service went public in 1939 and lasted for about ten years. Autogiros couldn’t fly fast or far, and they couldn’t hover in place, but they were able to complete low-altitude flights that airplanes couldn’t manage, essentially hopping from post office roof to post office roof.

Highway Post Office Bus: 1941 to 1974

This post office on wheels was inspired by railroad service and designed to reduce lag time by allowing postal workers to sort parcels while in transit. Their introduction was prompted by the fact that many Railway Post Office trains withdrew from service as rail traffic declined; the buses essentially served the same purpose, just on highways. The first batch of bright red, white, and blue buses, built by the White Motor Company, came equipped with distributing tables, letter cases, and enough space to hold 150 mail sacks. The buses could only hold enough gas for 150 miles, so each route was planned out to be 300 miles total, out and back.

Advances in automated sorting and a major restructuring of the postal system eliminated the need for on-the-go organization. In the early 1970s, the Post Office Department made the decision to send mail to a central location where high-speed sorters would route it.

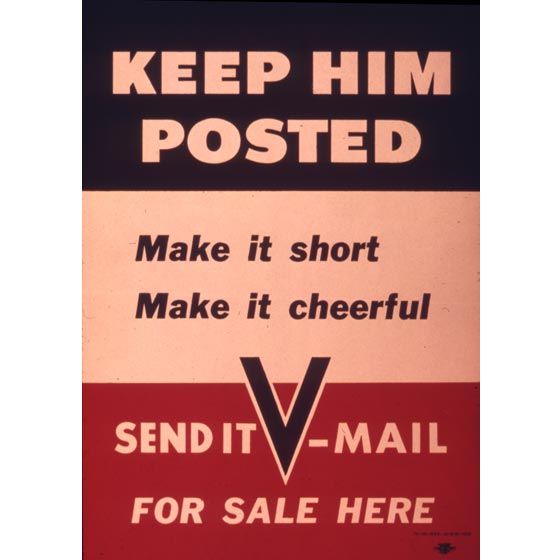

Victory Mail: 1942 to 1945

Another innovation borne out of wartime restrictions: In order to keep correspondences flowing between soldiers and the home front without sacrificing precious cargo space, the postal service introduced Victory Mail—or V-mail. Each letter, limited to 700 words, would be written on regular stationery, then photographed (after clearance by government censors); that image was transferred to a roll of microfilm for transportation. Using this method, 1,600 letters could be stored on a cigarette-pack-size roll of film, shrinking 37 mail bags to the size of one. Upon reaching the troops, the images of letters would be restored to a readable size and then printed back out on paper for their recipients to read.

The Mailster: 1957 to 1967

The Westcoaster Mailster was a three-wheeled vehicle that got up to 35 mph, boasted 7.5 hp, and allowed each delivery person to haul an unprecedented 500 pounds of mail. Its compact size and maneuverability were ideal for getting around the flat, smooth roads of recently developed suburban areas. By the end of the 1950s, Mailsters comprised one third of the USPS fleet; the number in use peaked at 17,700, in 1966.

While higher-ups in the postal service were more than enthusiastic about the Mailster's potential, the people actually driving it hated it, according to Nancy Pope of the Smithsonian National Postal Museum. Complaints from letter carriers assigned to Mailsters ranged from the front wheel getting stuck in trolley tracks to constant breakdowns, Pope says, and even one report of a massive dog toppling the vehicle. Furthermore, obstacles like snow (or even tight corners) rendered the Mailsters virtually useless. After years of complaints and malfunctions, the Postal Service realized that all the upgrades in the world wouldn’t make the little vehicles as safe and reliable as a Jeep. So they discontinued the Mailsters and replaced them with actual Jeeps instead.

Missile Mail: 1959

In the years following the Second World War, the volume of mail increased by more than 30 percent. Postmaster General Arthur Summerfield called for a new means of delivery to satisfy the growing demand—and thus, Missile Mail was born. On June 8, 1959, the Navy submarine USS Barbero launched a Regulus cruise missile filled with 300 commemorative letters off the coast of Florida in a demonstration-slash-publicity stunt. It was also a subtle Cold War boast; if the U.S. military was capable of such precision that missiles could be used for mail delivery, it was no stretch to think that they could also pull much less innocuous deliveries to U.S. enemies.

The missile made a flawless descent after soaring for 22 minutes, but the letters still would have needed to be removed, transported, sorted, and routed had it been an actual delivery. Following the successful demonstration, Summerfield declared, "Before man reaches the moon, mail will be delivered within hours from New York to California, to Britain, to India or Australia by guided missiles. We stand on the threshold of rocket mail." Despite the success of the initial experiment, the USPS never revisited the idea of missile mail—probably because in the end, it was much cheaper to deliver mail by airplane.

Segway: 2002

Soon after it was unveiled in 2001, the Segway was introduced as an experimental vehicle into the U.S. postal fleet. By attaching courier bags, the Segway promised to reduce physical strains associated with lugging sacks of mail while increasing the rate of delivery. But experiments in Virginia quickly proved that it wasn't efficient for deliveries. While a sidewalk in disrepair or curb can be tricky enough on a Segway, a flight of steps is impossible. Also, in areas where a letter carrier would just walk across front lawns, they were now forced to go up and down every driveway. The device lacked adequate storage space, and usually couldn’t make it through a full route on one charge. The Postal Service eventually abandoned experiments with the Segway.

Electric Vehicles: 2006 to Present

Although the USPS has been messing around with electric vehicles since the turn of the 20th century—an electric car promoter demoed a vehicle in Buffalo, New York, in 1899—EVs in our current understanding of the term first came to the Postal Service in the early 2000s. The Postal Service’s enthusiasm for electric vehicles has often outstripped the support of the vehicle-makers themselves. Mail workers experimented with Daimler-Chrysler EPICs, which were well-liked by drivers but which the company wanted back, and Ford Electric Trucks in California (until Ford canceled its EV program in 2002). From 2011 to 2013, the Postal Service tested ten Navistar eStar two-ton electric step vans, which could travel 100 miles on one charge; eventually, Navistar discontinued those vehicles as well.

The USPS is currently in the midst of creating a new fleet of vehicles; among the prototypes under consideration are all-electric trucks from Karsan and Mahindra.

Self-Driving Cars, Delivery Robots, and More: Future

In late 2017, the USPS Office of the Inspector General published a white paper on how the Postal Service might incorporate autonomous vehicles into its fleet; the following spring, another white paper on mail-delivery robots followed.

Semiautonomous car tests are already under way: The USPS has partnered with the University of Michigan to develop an Autonomous Rural Delivery Vehicle, which it hopes to roll out by 2025. In the fall of 2018, Jalopnik reported that Mahindra, already in the running for the next USPS fleet contract, was also tinkering with a partially autonomous prototype. A carrier would still need to sit behind the wheel, ready to take over in case of emergency, but they could focus on sorting between stops rather than watching the road.

As for robots—the OIG ran a survey to accompany their white paper last year, and found that 50 percent of respondents liked the idea of solo robots delivering their mail, and even more—57 percent—liked the idea of “helper” robots, which would carry the mail and follow the human carrier. The Norwegian postal service tested out delivery robots last November and December; although the USPS is not currently testing prototypes, they could soon follow.