Toledo was a place where you could fight a man for money.

At the dawn of the 20th century, the boom town—billed as where the rails and water met—was growing and prosperous. Its location on the southwestern shore of Lake Erie made it a major port, bringing with it the industries that inspired the slogan, “You will do better in Toledo.” The population had swelled from 13,768 in 1860 to 131,822 by the turn of the century, making it briefly the third-largest city in the state, surpassing Columbus, and the 26th-largest city in the country. Toledo’s growth came from immigrants, predominantly from Eastern Europe and Mediterranean countries, to work in the factories (largely with the auto industry; more than a century later, auto and auto parts companies remain major employers) and glassmaking facilities belching smoke into the sky above the city—the price of progress.

It was also a tough town. Reform-minded mayors were unable to stem the tide of slums, crime, and gambling. Toledo would become a center of organized crime and an important stop for bootleggers smuggling whiskey from Canada. “Toledo, Ohio, in the heart of the Midwest, bordering the western shore of Lake Erie and the Michigan line to the north,” Jack Dempsey wrote in his autobiography, “was in those days a haven for prominent gamblers and hustlers who were on the lam.”

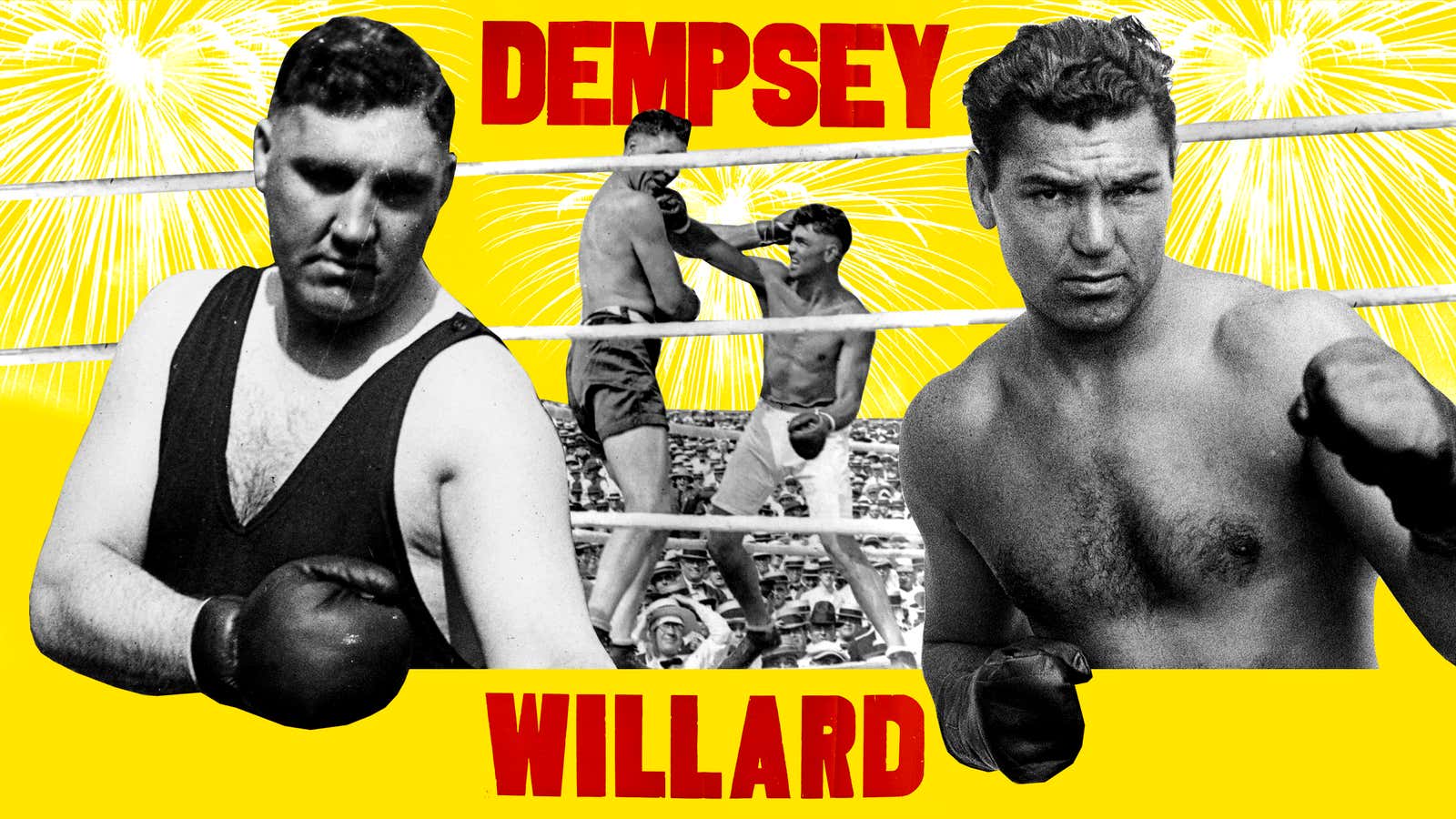

In sum, it was the perfect spot for a heavyweight prizefight. So, in 1919, when Dempsey, then a hungry challenger who’d made his name as a brawler in mining camps out west, took on champion Jess Willard, a giant of a man and an early “Great White Hope,” Toledo was chosen for its ease of access as much as for its moral flexibility.

Dempsey vs. Willard, on the Fourth of July, was supposed to be the biggest sporting event in American history, the first million-dollar prizefight, but scalding temperatures and a comedy of errors combined to keep attendance down. The fight itself was one for the ages, attended by figures from the world of politics, entertainment, and the nascent field of organized crime. It was the start of a legendary career for Dempsey, propelled promoter “Tex” Rickard to fame and fortune, and led to boxing becoming one of the most popular sports in America for a generation.

“The Roaring Twenties,” Jimmy Breslin wrote, “actually started in July of 1919 in Toledo, Ohio.”

At the center of it all was Rickard, a former town marshal who went to Alaska to make his fortune and stumbled into promoting boxing, which was then still an outlaw sport. It might be hyperbole to say that George Lewis “Tex” Rickard was born in a hail of gunfire—but not by much. He was born Jan. 2, 1870 outside of Kansas City, where the Rickards’ neighbors were Frank and Jesse James, a month removed from their first major robbery. The James Gang were exchanging shots with a posse while young Rickard came into the world.

He quit school at nine and by 11, he was on the trail as a cowboy. At 23, he was elected marshal of Henrietta, Texas, where he acquired his nickname and a wife, Leona, who gave birth the following year to a son, Curtis. The son didn’t live long, and Leona died soon after childbirth as well. With nothing keeping him in Texas, he set off for Alaska, following tales of gold-rush fortunes being made left and right. Not for him, though; a decade later, he was in Goldfield, Nevada, where he first discovered he had a gift for promotion. For a fight between Joe Gans and Battling Nelson, Rickard drew out the $30,000 purse in $20 gold pieces and had it displayed in the front window of a local bank, drawing not just curious onlookers, but media attention from the West Coast. Four years later, Rickard promoted the fight in Reno between heavyweight champion Jack Johnson and James Jeffries, who had come out of retirement for the bout, as the “Fight of the Century.” It was a decisive victory for Johnson.

Johnson’s championship was met with horror by white boxing fans and promoters, who continued to search for a white heavyweight champion. They found a challenger in Jess Willard, a Kansas native who, like Rickard, was a cowboy before taking up the sweet science at the comparatively old age of 27. The New York Times reported that Willard became a boxer after he’d become too big to ride on horseback. Willard met Johnson in Cuba in 1915, and defeated Johnson in the 26th round.

Little more than a year later, Willard defended his title for the first time ... sort of. Boxing was a fine exercise and a manly art, supported by the likes of Theodore Roosevelt and used for training in the armed forces, but prizefighting—a spectator sport involving payment and titles changing hands—was still regarded as an illicit practice, rife with criminals and gambling. So Willard’s fight against Frank Moran at Madison Square Garden—Rickard’s New York debut as a promoter—was an exhibition. After 10 rounds, both participants were still standing, so there was no official decision. But newspaper writers at ringside kept their own scorecards and declared it a successful title defense for Willard. But he needed another one—and Rickard needed another fight to promote.

William Harrison Dempsey was born in 1895 in a Colorado mining town that inspired Damon Runyon’s nickname for Dempsey: The Manassa Mauler. His schooling ended after eighth grade, and he went to work in the mines, boxing on the side. His mother told him bedtime stories of John L. Sullivan, and he was determined to be a boxing champion. Dempsey would stride into bars and use one of Sullivan’s lines: “I can’t sing, I can’t dance, but I’ll lick anyone in the house.”

In 1916, Dempsey ventured to New York but amounted to little (he said in his autobiography he refused to take a dive and was blacklisted, which is a plausible story). He returned west, working in a shipyard in Washington and spending time trying to reconcile unsuccessfully with his wife in San Francisco. While in Oakland, he intervened in a bar fight. The victim, Jack “Doc” Kearns, was a former boxer turned manager who had followed Dempsey’s career from afar, and saw enough in him that when Dempsey went back to Colorado for his brother’s funeral, Kearns wrote a letter and enclosed a train ticket and a five-dollar bill. “The five dollars was for meals on the train,” Dempsey later recalled. “That’s what bowled me over. I never had enough money to eat in a train diner.”

With Kearns’s guiding hand and savvy promotion, Dempsey quickly positioned himself for a title shot against Willard. “I have $10,000 to lay on the line that my man Jack Dempsey can lick any two heavyweights alive, taking them on one after another in the same ring and on the same night,” Kearns announced.

But Willard, who had already killed one man in the ring, was truly afraid of that happening with Dempsey, who was five inches shorter and 60 pounds lighter. (Willard would hold the record as the tallest heavyweight champion for nearly a century until Vitali Klitschko claimed the title in 2004.) But Dempsey was also 13 years younger—and “hard as a keg of nails,” as Kearns put it.

A deal was reached for Dempsey to fight Willard, who would receive $100,000 for just his second title defense. Rickard offered Dempsey $25,000, but Kearns sought $30,000. The claim was put before a jury of sportswriters, who cut the baby in half and settled on $27,500. The contract was signed in Weehauken, N.J.—not far from where Alexander Hamilton had his fateful and fatal duel with Aaron Burr—because even signing a prizefighting contract was a crime in New York City, where the sport was completely illegal after the death of Young McDonald in the ring in 1917.

That, of course, led to the question of where the fight would be held. Eyes turned to Europe, but after recovering from the bloodiest war in human history, the continent had no appetite for a fight. Tijuana was suggested, as was Nevada, which had recently passed a law allowing fights up to 25 rounds. Rickard was looking for someplace on the East Coast. It was an impasse.

Addison Thatcher wanted to see the fight in Toledo. Thatcher was descended from Boston blue bloods, but his time on Toledo’s docks had acquainted him with the seamy side of life—he bore a hole in his right ear from getting shot when he tried to subdue a would-be mugger—and gave him a certain practicality. A Blade reporter years later said Thatcher’s motto was “take a little, leave a little and no one will get mad at you.” Thatcher knew a prizefight would benefit the city—which would elect him mayor a decade later—and went to New York to sell Rickard on it. “What do you want out of it?” Rickard asked. “Seven percent of every dollar for the mayor’s charity fund,” Thatcher replied. Knowing how the world worked, Rickard asked, “How many politicians do I have to take care of?” “Not one,” Thatcher promised.

Well, that was stretching the truth a little. Ohio Governor James Cox didn’t have to be bought off, but Rickard did have to make sure he was on board. So Rickard and Kearns snuck into an Elks convention where Cox was speaking and impressed upon him that the fight would be beneficial for the city and state. (In one telling, Kearns suggested he had many relatives who were eligible voters in Ohio.) Cox approved the fight, and because of Ohio law, it would technically be an exhibition, with each fighter taking their payout in Liberty Bonds.

So the fight had a city. But where in Toledo? The Mud Hens, the city’s minor league baseball team, played at Swayne Field, but with a capacity of 11,000 it was far too small to hold the crowds Thatcher and Rickard anticipated. So Rickard commissioned the construction of a new wooden facility in Bay View Park, on the edge of Maumee Bay, where the Maumee River emptied into Lake Erie. Initially, Rickard anticipated seating 50,000, but early ticket sales were so brisk that he nearly doubled the venue’s size, making it the largest sporting venue in the country, dwarfing what was then the biggest, the Yale Bowl in Connecticut. It was also bigger than the Roman Coliseum.

The fight was covered by more than 200 reporters, including a virtual who’s who of sports journalism at the time, including Nat Fleischer, Damon Runyon, Ring Lardner, and Grantland Rice. Bat Masterson, the former marshal whose exploits would inspire movies and a 1950s television show, collected spectators’ weapons at the door, assisted by his old friend Wyatt Earp. Actor Tom Mix was there, Charlie Chaplin bought a section of tickets, and Douglas Fairbanks and his brother-in-law Jack Pickford made the trip from Los Angeles. Actress Ethel Barrymore could be found in the women’s section of the arena—separated from the rest of the stands by barbed wire. Governor Cox was also in attendance, as was a man who identified himself as Al Brown, who sat ringside after meeting two members of the state boxing commission and leaving their pockets a little fuller. Years later, Kearns was asked if the commission members knew they had met a young Al Capone. “Why certainly,” Kearns said. “They were politicians. They weren’t going to take money off a complete stranger.”

July 4 was fight day, and it was hot. Dempsey said the mercury crossed 106 degrees. Nat Fleischer estimated the temperature between 103 and 110 degrees. In his biography of Tex Rickard, Charles Samuels said it was 112 degrees. The New York Times said 120. Damon Runyon said it was “hotter than a boiled potato.” Breslin wrote, “the temperature that morning was anything you said it was.”

The brass band hired to play between fights couldn’t, because the metal on the instruments was so hot, it burned their hands. Sap oozed out of the fresh plywood used to build the arena—ruining the pants of people who had the misfortune to sit without a cushion. Seymour Rothman, who was a child of 5 during the fight but went on to a lengthy career with the Blade, said 50 years after the fight, “I’ve run into 20,000 who say they doled out ice water.”

Planes circled overhead and military balloons were used to take overhead photos of the imposing but sparsely populated stadium, built for 80,000 but holding only around a quarter of that. The fight had been a victim of its own hype, as people believed tickets, transportation and lodging were going to be prohibitively expensive and hard to come by. Rickard bore a grudge against railroads for not running extra trains.

The heat also kept the crowds away. (A dozen years later, another heat wave around the Fourth of July depressed attendance so much at the U.S. Open at the Inverness Club in Toledo, the USGA decided the next year to change the tournament’s date to June, where it’s remained ever since.) The million-dollar purse was not to be this time—but it was reported that as much as $2 million was wagered on the fight.

That included $500 by Lardner, and an undetermined but doubtlessly large amount by other writers. “Because the newspaper people bet money and established a conflict of interest, and had personal venom and exhilaration through each second of the contest they covered, stories were horribly biased and always a thrill to read,” Breslin later explained in his biography of Runyon.

Dempsey’s timekeeper bet $2,000, while Kearns put down $10,000—from Dempsey’s purse!—on a first-round knockout at 10-to-1 odds (overall, Willard was a 6-to-5 favorite). And it almost looked like he’d collect.

Willard and Dempsey started the fight with a couple haymakers, feeling each other out, before Dempsey smashed Willard with a left hook to the jaw, knocking the big champ down for the first time in his career. When Willard arose, he absorbed a fusillade of punches from Dempsey and went down six more times in the last minute of the first round. Referee Ollie Pecord had gotten to a count of about seven when the round ended—but the bell didn’t ring.

Because it wasn’t working.

To everyone in the arena, it looked like the fight was over, and Kearns hustled Dempsey out of the ring, no doubt thinking about the bet he’d collect on. Willard was dragged back to his corner “like a sack of oats,” Grantland Rice wrote. In fact, the Toledo News-Bee went to press with an extra edition saying that Dempsey had beaten Willard in one round.

But once they realized Willard had been saved by the nonexistent bell, Dempsey was quickly ushered back to the ring. At that point, it was just a formality.

“Dempsey fought with all the necessary brutality of his craft,” Rice wrote the next day’s New York Tribune. “With the championship now in plain sight, with the goal of his dreams just at the end of another hook, with all the world before him at twenty-four—lifted from a tramp two years ago to a millionaire’s income ahead—he hooked those salvos of rights and lefts, shifting from Willard’s mutilated face to his quivering body, with only a few pauses between his deadly blows.”

By the third round, Dempsey regarded Willard as an object of pity. Willard’s corner threw in the towel before the start of the fourth. “The right side of Willard’s face was a pulp,” Runyon wrote. “At the feet of the gargantuan pugilist was a dark spot which was slowly widening on the brown canvas as it was replenished by the drip-drip-drip of blood from the man’s wounds.” A day earlier, Runyon had likened Willard to Goliath. Now he spoke of Dempsey as a “mountain lion in human form.”

The gate turned out to be $452,224, not the million Rickard hoped for, but still a handsome sum and a longtime record for a fight in Ohio. The arena, with 1.75 million feet of lumber—enough to stretch from New York to Chicago, Rickard boasted—was sold for $25,000 to a company that used it to build a factory in Toledo. Rickard paid the city $30,000, and he ended up with a profit on paper, but didn’t get the windfall he’d hoped for. But the publicity he got promoting the fight—and the star that Dempsey became—would soon make him one of the richest men in America.

A year after the Dempsey-Willard fight, Rickard got the promotional contract for Madison Square Garden, thanks to the backing of John Ringling, who wanted his circus at the Garden—and everyone else’s out. The venerable arena was already a sporting landmark, but had been unable to turn a profit for decades. Of course, by the time Rickard was the venue’s promoter, boxing was legal again in New York, thanks to Jimmy Walker, who would go on to be elected mayor of New York City, resign in disgrace amid a corruption scandal, and then be played by Bob Hope in the movie Beau James.

With Rickard’s acumen, a new Madison Square Garden was built in 1925. Among the tenants was a National Hockey League team, the Americans. They proved so successful that Rickard wanted his own team at the Garden. His began play the following season, and were quickly nicknamed “Tex’s Rangers.” The Americans were relegated to second-class status and were blinked out of existence during World War II. The Rangers remain a part of the NHL and a fixture at Madison Square Garden to this day.

In 1921, Dempsey fought Georges Carpentier. Though the Walker Bill legalizing boxing in New York was signed into law by Gov. Al Smith, his successor, Nathan L. Miller, took a dim view of boxing and refused to sanction a fight between the two of them at the Polo Grounds. So Rickard found a plot of land called Boyle’s 30 Acres across the river in Jersey City and erected another octagonal wooden stadium to accommodate the fight. This time, everything he thought would happen in Toledo came to pass, as more than 80,000 people came, and Rickard finally got his million-dollar gate.

Dempsey and Doc Kearns parted ways acrimoniously, as the champ found himself caught between his manager and his new fiancée, Estelle Taylor (and between Kearns and Rickard, too). Rickard wanted to see the champ fight Gene Tunney. The two met Sept. 23, 1926, at Philadelphia’s new Sesquicentennial Stadium (later renamed for John F. Kennedy, and probably best known as the regular site for Army-Navy football games), where Tunney beat Dempsey in a 10-round decision—the first time the heavyweight crown had changed hands on points. “Honey, I just forgot to duck,” Dempsey told Estelle, a line recycled by Ronald Reagan after he was wounded in an assassination attempt in 1981.

The rematch between Dempsey and Tunney was 364 days later, at Soldier Field in Chicago. Boxing had finally entered the mainstream. The million-dollar fight earlier in the decade seemed almost quaint. The total gate for this fight was $2.658 million, with $990,000 going to Tunney and $450,000 to Dempsey. Nearly 105,000 people packed the stadium on the Lake Michigan shore. It was the place to see and be seen. “Kid, if the earth came up and the sky came down and wiped out my first ten rows, it would be the end of everything because I’ve got in those ten rows all the world’s wealth, all the world’s big men, all the world’s brains and production talent,” Rickard boasted to sportswriter Hype Igoe before the fight. “Just in them 10 rows, kid, and you and me have never seen anything like it.”

Tunney was outpointing Dempsey for the first six rounds, but in the seventh, Dempsey knocked the champ down. But because Dempsey hadn’t retreated to a neutral corner, the count against Tunney—known forever after as “The Long Count”—didn’t start immediately, giving him enough time to recover and ultimately win, again in a 10-round decision. “In defeat, he gained more stature,” Shirley Povich wrote of Dempsey. “He was the loser in the battle of the long count, yet the hero.”

Dempsey hung up his gloves after the fight and became partners with Rickard. He accompanied Rickard to Miami in December 1928. The trip was ostensibly to promote a fight between Jack Sharkey and Young Stribling, but Dempsey recalled that Rickard had no end of opportunities.

He also had a stomachache, which a local doctor diagnosed as heartburn. A fever developed and on Jan. 2, Rickard’s 59th birthday, he was taken to the hospital. The stomachache was an inflamed appendix. Dempsey held Rickard’s hand as he died four days later.

Rickard’s body was taken by train back to New York. It was a frigid day when he returned to Grand Central Station, but thousands lined the streets to see his $15,000 bronze casket taken up Eighth Avenue to Madison Square Garden, where he would lie in state. Even in death, Tex Rickard could draw a crowd.

“New York is a town where people would not cross the street to see any man in his coffin,” Edwin C. Hill wrote in the New York Sun. “But they came, the people who had been waiting, and they were of every sort and degree … actresses in sable and ermine, little stenographers, women of society, servant maids, some of the six hundred millionaires that Tex liked to talk about so much, riffraff of the boxing game, bunkers, gunmen, owners of department stores and dope sellers, artists, playwrights, journalists, vagabonds, city officials, clerks, day laborers in their stained blue jeans. There were without doubt men wanted by the law in that heterogenous double line, but it seemed that they, like the men who keep the law, had that equal admiration and respect that Rickard seemed able to draw from all classes of the human animal.”

Rickard was not a religious man, but to make sure all the bases were covered, a Baptist preacher, an Episcopalian minister, a Catholic lawyer, and a Jewish judge commended his soul to the afterlife. “Some wags remarked that it didn’t matter whether Tex went to heaven or hell,” Dempsey said in his autobiography. “He’d probably wind up promoting a match with the other side anyway.”

Over the next six years, Dempsey followed a path that would become well-trod by boxers. He got divorced, and he ended up refereeing some boxing matches and participating in some exhibitions himself because he needed the money. He also invested money with a friend and former sparring partner, a Syrian bantamweight fighter named Bobby Joe Manziel, who went into oil wildcatting. (You might have heard of Bobby’s great-grandson Johnny.)

Prohibition was repealed in 1933, and two years later, Dempsey opened a restaurant at Eighth Avenue and 50th Street—across the street from Madison Square Garden. Among his employees, briefly, was Jess Willard, of whom Dempsey diplomatically said, “In his own unique way, he tried.”

Dempsey commissioned a painting by James Montgomery Flagg of him fighting Willard and unveiled it in 1944. Willard was invited, but sent his regrets in a telegram, saying, “Sorry I can’t be there. But I saw enough of you 25 years ago to last me a lifetime.”

Dempsey even made his peace with Doc Kearns, or so he’d thought. Kearns died in 1963, but he had one last trick up his sleeve. His autobiography, Million-Dollar Purse, was excerpted posthumously in Sports Illustrated the following January, claiming he’d loaded Dempsey’s gloves with plaster of Paris. “I’m just glad that Kearns finally was man enough to admit it,” said Willard, reached at his home in California. “First time Dempsey hit me, I knew those gloves were loaded.”

Trainer Jimmy Deforest denied Kearns’s account, as did Dempsey, who sued Sports Illustrated. The parties settled out of court, and a year after Kearns’s article was published, an editor’s note in Sports Illustrated said Kearns’ story appeared completely unfounded. (This seems as good a place as any to mention that Kearns’ co-author on his autobiography was Oscar Fraley, a UPI sportswriter who’s probably best known for being the co-author of Eliot Ness’ memoir, The Untouchables, which, like Kearns’ memoir, was released posthumously and is of dubious veracity.)

Jack Dempsey’s Broadway Restaurant—it had moved to the Great White Way in 1947—closed in 1974, two years after it was immortalized in The Godfather as the location where Michael Corleone was picked up by the Turk and Capt. McCloskey before their fateful meeting. The painting of Dempsey beating Willard that hung in the restaurant was donated to the Smithsonian, where it remains on display today at the National Portrait Gallery.

Willard died in 1968 at the age of 86. At the time, he was the longest-lived former heavyweight champion. In 1983, Dempsey died—at the age of 87. He’d beaten Willard one last time.

Vince Guerrieri is an award-winning journalist and author in the Cleveland area. He likes Lake Erie perch sandwiches, Jim Traficant and long walks on the field at League Park. His website is vinceguerrieri.com, and you can follow him on Twitter @vinceguerrieri.