Reaching for your favourite sugary treat when you need cheering up, or deserve a reward, is something so many of us do.

But the sweet tooth wasn’t invented at the same time as the jelly baby (which was around 1864, and more on that later). In fact, for thousands of years, people have been enjoying sweets as part of daily life. BBC Bitesize has untwisted the wrappers from a history of confectionery - and we promise not to put them back in the tin afterwards.

Suffering for your sweet

Research by confectionery historian Tim Richardson shows that in 8000BC, cave paintings depicted people raiding bees’ nests and risking multiple stings for their sweet honey, while Sanskrit texts from 2000BC describe Indian sweets, made using milk and sugar, among other ingredients.

Confectionery expert Andy Baxendale, who has worked in the industry for more than 20 years and featured on the BBC Two documentary series The Sweet Makers, told Bitesize how items made from honey and nuts were found in Egyptian pyramids, so the equivalent of pick’n’mix dates back thousands of years.

But sweets as we know them today don’t have quite as long a history.

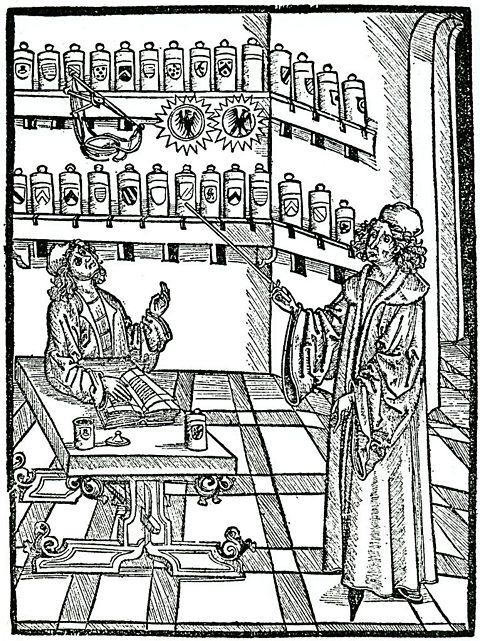

Andy said: “In terms of what we would recognise as sweets, they had their roots in apothecaries, the precursor to chemists. So if you take something like an aniseed ball, they were originally designed to give to people along with nasty tasting early drugs so they could take the taste away.”

A spot of comfit eating

In the Tudor era, comfits were popular too. These were spices, seeds, nuts and other small items given a hard sugar coating. They are thought to be one of the earliest sugared sweets and it is believed they originated at apothecaries in the Middle East as treatments for indigestion, brought into Europe as part of trading between nations.

In these times, the ownership of sugar was considered a real status symbol. It was so valuable, it was kept locked away. Rich households would employ their own confectioner. Royal confectioners, with their sought-after skills, could earn an annual wage three times that of someone working as a labourer. Sugar banquets were held by the aristocracy, where most of the items on the table were crafted from the stuff, and edible - including the plates. Coriander comfits would be served at these banquets as they were thought to aid digestion after such a big feast.

The increase of sugar coming in to Britain was directly linked to the trade of enslaved people. The Tudor period saw the beginnings of the trade, which would expand in the 17th Century. The West Indies was a rich source of sugar cane, where enslaved people brought over from Africa worked on the plantations in extremely hard conditions.

A Yorkshire-born favourite

In the 1760s, a sweet that can still be bought in the UK today made an appearance. It also had links to the apothecaries. Liquorice had been introduced to Britain in around the 11th Century, brought by either monks or crusaders returning from the Middle East. It became known for having medicinal properties, to the extent that Pontefract Castle’s former dungeons were used to store liquorice roots by 1720 as demand grew.

An apothecary in the Pontefract area, George Dunhill, added sugar to the liquorice to create a chewable version that was purely for pleasure. The round, black discs became known as Pontefract cakes. By the 19th Century, 25,000 cakes a day were being made in factories across Yorkshire, each one stamped with an image of Pontefract Castle.

A time of great change

Although the enslaved people working on the sugar plantations were not freed until much later, the slave trade in Britain ended in 1807. The abolition of slavery was pivotal in its impact on humanity. For the traders and the sweet industry, it had a series of economic consequences, one of which was sugar became less plentiful - and therefore more expensive. An alternative to cane sugar was found in sugar beet. It tasted the same, but was grown in mainland Europe and cheaper to import.

The Victorian era also saw advancements in technology. The industrial revolution saw half the population living in towns linked to their jobs. Sweet shops became more commonplace and confectionery became something people of all classes ate. For the first time, sweets were made with children in mind as well.

Mass production meant it was easier to make larger quantities of sweets. In 1879, the French confectioner Claude Gajet brought the recipe for the popular French sweet, the pastille, to Rowntree, one of the country’s biggest sweet manufacturers. The recipe has never been made public but the pastille, in different fruit flavours, became popular and is still available today.

So ready for this jelly

Another product of Victorian industry is reported to have happened by accident. In 1864, an Austrian confectioner was working for the company Fryers of Lancashire on some jelly-based sweets.

The mould he made for a series of jelly bears didn’t come out as planned, producing sweets which looked more like babies. Rather than reject them, they went to market under the unusual name Unclaimed Babies. At this point in history, unclaimed babies were part of life, with infants left outside churches, but the name never lasted. From the 1950s onwards, they became better known as Jelly Babies.

By the dawn of the 20th Century, chocolate stopped being something that was drunk and the art of turning it into a solid bar had been perfected. Frys, a British company, produced the first chocolate bar in 1847, finding that cocoa butter worked well in the mix. Over in Switzerland, chocolatier Rudolf Lindt had perfected a technique called conching. Using milk powder, the intense kneading process helped make chocolate smoother than it had been before.

Treats for everyone

Chocolate was still a luxury in the early 1900s and the ‘fancy boxes’ (like today’s selection boxes) produced by companies like Cadbury’s cost as much as a working class family’s weekly food budget. As time went on, mass production brought chocolate to a wider customer base. By the 1930s, bars such as Flake, Aero and Kit-Kat were regular sights in sweet shops, and affordable to working people and their families.

With sweets no longer exclusive to the aristocracy, an average of 33 bags a sugar was eaten per person in Britain by 1900. In the 1920s, it was even possible to grow sugar beet on British soil. Sugar rationing again affected supply during the Second World War, but from the 1950s onwards, sweets and chocolate became treats affordable to almost every home.

Even now, the confectionery industry is worth £6bn in the UK alone. So why have sweets managed to remain such a popular part of our lives? Andy thinks there’s a simple explanation, linked to escapism when times are tough, or if people just need a moment of simple pleasure that won’t break the bank.

He said: “I used to have a sweet shop and I found people always turned to you for cheap, comforting food. Even when there was a recession, people would still come to us.”

Making profit from a tray of chocolate brownies

Read this if you want to learn how to make money from chocolate.

Myth-busting food origin stories

Chocolate chip cookies, crisps and Caesar salad all have legendary histories, but are they true?

Six key events in black history you may not know about

The Bristol bus boycott, the killing of Emmett Till and other events you may not have heard about.