📚 Stay up-to-date on the Book Club

Catch up on the latest Boston.com Book Club pick and join the virtual author discussions.

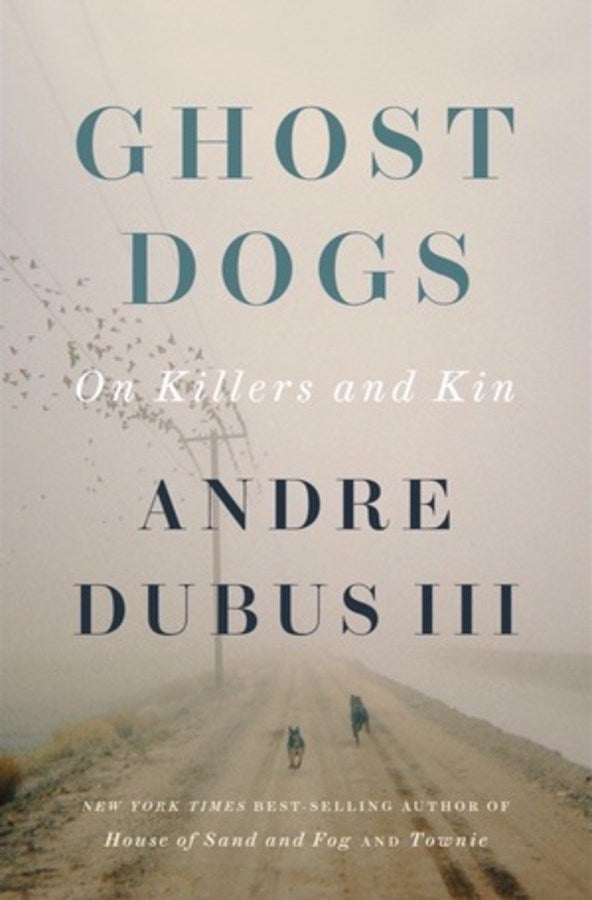

If you’re not at least a little embarrassed after writing a memoir or personal essay, you didn’t do it right. That Andre Dubus III tells me he’s “mortified” at parts of his new essay collection, “Ghost Dogs: On Killers and Kin,” tells you all you need to know.

I read it in 48 hours. Couldn’t put it down. While the essays are previously published — characters and life aspects are newly introduced in many essays — they feel written yesterday.

Most are cards-on-the-table soul-barers with underlying themes of masculinity, fatherhood and family. Baldly honest standouts include “Relapse” — feeling, in his 40s, his old teenage urge to fist-fight. In the backbone essay, “If I Owned a Gun,” he admits to the power he feels, and beauty he can see, in a gun, even though he detests them.

I was gripped by “Golden Zone,” about his stint helping a bounty hunter track a killer in Mexico, and, while there, hiring a prostitute, which feels like a short film. The subtitle shines through strongest in “Pappy,” where we learn his grandfather may have once killed two men for tailgating.

The latest release from the bestselling author of “Townie” and “The House of Sand and Fog” is Boston.com’s Book Club Pick for March. I had to ask Dubus about it.

I found, in our recent phone interview from his Newbury home, that while his writing is serious, in conversation, Dubus is gregarious, charming, and at times downright hilarious. At one point he breaks into a brogue, and tells me he recently learned, “I’m 40 percent Scottish, for chrissakes!”

“Alright! Let’s shoot the s—,” Dubus, 64, says at the start of the call.

He “loves people,” he tells me, and you can tell he’d be comfortable as a professor (he teaches as UMass-Lowell) and public speaker (“I stand up and I talk. I don’t know what I talk about.”)

We talked bounty-hunting, going undercover in Mexico, his cameo with Ben Kingsley, why dogs haunted him, and more.

Dubus: I’m in Newbury, sitting in a big reading chair in my living room in this house I was able to build with my bare hands, disciplining myself not to drink more coffee. The sun’s coming through the skylights onto my books on all the shelves. And it’s a beautiful day.

I’m blessed. It’s that simple.

A few years ago, it occurred to me I had about 40 essays, some had won awards. I thought, “I like essay collections. I think I might have one.”

I love the essay form. You probably know it comes from the French word “essai,” which means to attempt or try. That’s the most honest approach to writing — it’s just an attempt to go deeper with words.

I’m drawn to ambiguity. I teach a lot of writing workshops. [Once] this woman in her 80s raised her hand. She said: “I was an accountant all my life and it made my writing so bad because I looked at the world in black and white. Know what, y’all? I finally learned to play in the gray.”

[laughs] Isn’t that great? So I can see all sorts of gray in guns. Some are beautifully made. Yet I despise what they do. I want them all gone across the world.

With an essay, I try not to say anything. I try not to make a point. One of my favorite lines from Rumi: “Sell your cleverness and purchase bewilderment.” I try to step into my writing with bewilderment.

My oldest son is a screenwriter; he’s been eyeing that for a long time. That was in [my 2012 memoir] “Townie,” and I cut it because it felt like a whole story on its own.

I was the assistant to a bounty-hunter. I had a fake name. I still remember the gun — the U.S. Marshal handed me the photo of the killer [we were hunting.] I remember he had a pink tie. I remember how oiled the walnut of his piece was. As I was going down the elevator, I thought: “The f— am I doing?” And yet, I knew I was going to do it.

I worked in a halfway-house for convicted adult felons in Boulder. I met the bounty-hunter there, I call him “Christoph.” He had a bounty-hunting business with this fat cat lawyer. My girlfriend had just left me. I’m living alone, depressed. He sees I had some muscles and some attitude.

I trailed a diamond thief in Denver over three days. I did some other stuff. It was good cash money. I wrote in the mornings, so I liked night work. I found myself hunting a hitman in Mexico at age 23.

I’m mortified about hiring a sex worker (a scene in that story.) I’m a feminist. I think the whole thing is disgusting. But I did it because I wanted to know what it was like. I was this young man who wanted all kinds of experiences — my God, if there was a war, I would’ve signed up. That kind of naive, romantic passion.

I had a lot of one-night-stands. I’m a mill town kid who drank too much, I’d wake up with women, didn’t know their names; they didn’t know mine. Hiring a prostitute was no different. It was just another transactional experience. I realized: I didn’t need to do it literally, to be able to imagine it accurately. That was a big piece of learning for me.

No, I was a fighter. I was ready to tangle. But these guys had guns, man. I was so stupid. (The bounty-hunter didn’t want them to use guns.) I stopped doing it because I sold my first story to Playboy Magazine — they gave me $2,000 bucks. I had enough money to go home.

I’ll say one thing: “Townie” began to take on a narrative arc of its own. So I cut out things like looking for a hitman in Mexico, or working as an actor in New York — I got offered to be in a cowboy movie with Eric Roberts as my brother and Dennis Hopper as our dad.

I should write an essay about that.

I turned that down. And I friggin’ love Westerns, Lauren. But I spent weeks on a story and I was getting close to the end— I could just feel it. My manager called me: “Andre, they want you to do a screen test in L.A.” I said, “When would I have to go?” “Oh, tomorrow!” I looked at the story. I said, “Bill, I’m gonna have to pass.” He said, “Andre, do you know how many actors would cut off both their f—g legs for this?” I said, “I’m sorry.” I haven’t really written about this.

I should. I was as drawn to acting early on as much as writing. But I realized: I can go a year without acting. I can’t go three days without writing. But I did a cameo in the adaptation of my novel, “House of Sand and Fog.”

I actually sucked. I became friends with the director. I said, “I want to be in a scene with Ben Kingsley.” So he wrote me in, no lines, but I overreacted with my eyes. [After I saw it] I said, “F—! Why didn’t you tell me? I would’ve toned it down.”

No. How come? This is good. This is how I got ideas for us. Lauren, you’ve just helped me — I’m gonna put that down.

I totally repressed the memory of 18 puppies dying. One day I was drunk with my girlfriend, we were yelling, and it came out. I didn’t believe in repressed memories until then. I sure as hell shut the door on that.

One of my earliest memories is having my father take our beloved family dog out and execute it because he just didn’t like it. That was in my psyche. But my father was a public figure and people loved his work. I didn’t want to make him sound bad, so I didn’t tell anyone.

I really wanted to examine my relationship with dogs here. I would never hurt an animal. Why am I so dead inside about dogs? Writing that essay — this didn’t even happen in my memoir, Lauren — it changed my relationship with my dog, Rico.

Before he died. This is a horrible epilogue — you know how he dies? I f—g ran him over.

No! That was Dodo.

Yes! But you don’t have to put it that way.

What happened was Rico had gone deaf and blind. One night, I go out in my truck, I feel a bump. I said, “Oh, potholes.” I get back 20 minutes later and there’s my dog lying in the driveway.

I’m crying. I’m a mess. I’m looking at his box of ashes now. We got a new dog, Lottie, and it’s the first time I’ve openly loved a dog.

The honest answer is: I don’t know. Titles are hard because they have to somehow resonate throughout the whole book. It felt right. The opposite of “to remember” is not “forget” — it’s “dismember.” So in that sense, memory is reaching for the shards. In ways, these shards are ghosts.

It’s interesting: my editor wanted me to keep digging into that. But this is the sad truth: When he told me, at that time of my life, I was in so many fights that it just didn’t faze me. I feel horrible saying that now. But in my 20s, it didn’t bother me. I thought, maybe they lived, maybe they didn’t.

I was so full of rage. It was just what men did. But [I’ve since learned] gender is performance. Growing up when I did, I just wanted to be Clint Eastwood. Men who didn’t talk much, kicked serious ass when needed. If I were a kid now, would this whole masculinity thing mean as much to me? I don’t know.

It’s embarrassing but true. Maybe that’s why I’m always filled with such self-loathing after finishing a book because I tried to get really naked. And then I hate myself.

I’m mortified by that essay. I’m embarrassed that when I chose not to fight, it bothered me for weeks that my friends might think I was afraid. What am I, 10 years old? The relapse [of wanting to fight] felt the way an alcoholic must feel after being sober for years and then getting drunk.

Good question. Reading them over, there is the feeling that I’m getting older. A feeling that I’ve lived my life. That I have not shied from life. That I’ve stepped into life and wrestled with it. I’m grateful I found a way to express it.

Interview has been edited and condensed.

Lauren Daley is a longtime books journalist and freelance writer. She can be reached at [email protected]. She tweets @laurendaley1.

Catch up on the latest Boston.com Book Club pick and join the virtual author discussions.

Stay up to date with everything Boston. Receive the latest news and breaking updates, straight from our newsroom to your inbox.

Conversation

This discussion has ended. Please join elsewhere on Boston.com