There’s a mini-furor in the chattering classes over the proposition that the oldest Supreme Court justice, 69-year-old Sonia Sotomayor, ought to retire right now so that a Democratic president and a Democratic Senate can together secure a liberal successor. The argument is most vociferously being advanced by Josh Barro. He weakened the case he laid out in The Atlantic by dwelling on Sotomayor’s diabetes (not exactly an imminent death sentence) and then shifting to an attack on Democrats’ attachment to identity politics, as though Sotomayor’s Latino heritage is the only reason they aren’t running her off the Court. But there’s a premise in Barro’s proposal that needs discussion, as it has implications larger than the fate of a single justice: that nowadays, control of both the Senate and the White House is necessary if you want to make a Supreme Court appointment.

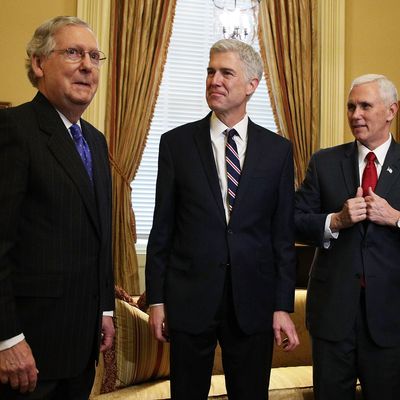

The grounds for that premise are obvious enough: Mitch McConnell’s audacious refusal to even consider confirming Barack Obama’s March 2016 nomination of Merrick Garland to fill the vacancy created by Antonin Scalia’s death just over a month earlier. That McConnell was acting strictly as a partisan warrior on this occasion was made clear in 2020, when he quickly discarded his stated prior opposition to presidential-election-year Supreme Court appointments and rushed Amy Coney Barrett’s confirmation through the Senate just weeks before Trump was defeated by Joe Biden.

You could argue that this was an extreme situation generated by the decadeslong conservative drive to capture the Supreme Court and particularly to reverse Roe v. Wade (which, of course, ultimately came to pass in 2022). But then again, when faced with the hypothetical situation of another Supreme Court opening and a Republican takeover of the Senate in 2022, McConnell would not commit to confirmation hearings for any Biden-appointed justice. My colleague Jonathan Chait promptly concluded: “McConnell made it clear that Jackson is likely the last Supreme Court justice Democrats will nominate for years, maybe even a decade or more.”

As it happens, Republicans did not flip the Senate in 2022, and there were no Supreme Court vacancies. But while McConnell has announced that he will step down as Senate leader in November, there’s also no reason to imagine that his successor will be more cooperative to a Biden administration if the GOP wins back the Senate this year, as the betting odds suggest they probably will. Indeed, the most frequent MAGA criticism of McConnell was that he was too comfortable with bipartisan Senate traditions and excessively courted the good opinion of bipartisan elites.

It’s also worth noting that although no Senate leader prior to McConnell explicitly rejected confirmation of any justices nominated by a president belonging to the other party, successful confirmations in such circumstances have — by coincidence if not design — become unusual. Of the current members of Supreme Court, only one, Justice Clarence Thomas, was confirmed by a Senate controlled by the party opposing the president’s. That was in 1991, and as you may recall, his confirmation did not come easily.

But divided control of the White House and the Senate is not so uncommon; it has been the situation in 20 of the last 50 years. Thanks to the odd configuration of Senate elections (in which only one-third of seats are in play in any one cycle) there’s no guarantee at all that one party’s success in a presidential election will carry over to the Senate. Given the current climate of polarization and the likelihood that this year’s presidential election will be exceptionally bitter (and perhaps once again contested), the odds seem low that Senate leaders of either party — particularly Republicans, since they’ve already set the precedent — will be open to paving the way to a Supreme Court confirmation by a president they despise.

Perhaps the bigger question is whether the abuse of Senate prerogatives by McConnell in blocking Supreme Court confirmation will soon leach over into other Senate confirmation arenas. Recent Senate leaders from a party other than the president’s have sometimes slow-walked lower-court confirmations, and occasionally it has become difficult to confirm Cabinet members. And thanks to the power of the minority in the Senate, you don’t even have to control that chamber to make confirmations difficult, as McConnell has shown in the case of Biden’s Labor Secretary designate Juli Su. More generally, as we saw in 2021, the filibuster enables Senate minorities to obstruct regular legislation quite effectively, which is the main reason so much important legislation currently has to be enacted via budget reconciliation bills that cannot be filibustered.

The struggle to keep the federal government funded in the current Congress is the most obvious illustration of the cost of divided government. But Senate dysfunction is a separate issue. It’s offensive to the constitutional framework that the holder of a lifetime Supreme Court appointment like Sonia Sotomayor should have to time her retirement to take into account calculations of future Senate election results, not to mention pundit’s estimates of her life expectancy. It’s another reason Supreme Court reform — perhaps limited terms, perhaps mandatory confirmation rules — needs to stay on the table even if there’s no Supreme Court vacancy at the moment. Eventually there will be vacancies that may go unfilled for extended periods of time, or until partisan polarization has somewhat abated, if ever.

More on politics

- Kristi Noem Killed Her Dog. Why Is She Telling Us This?

- Colin Jost’s Best Jokes at the 2024 White House Correspondents’ Dinner

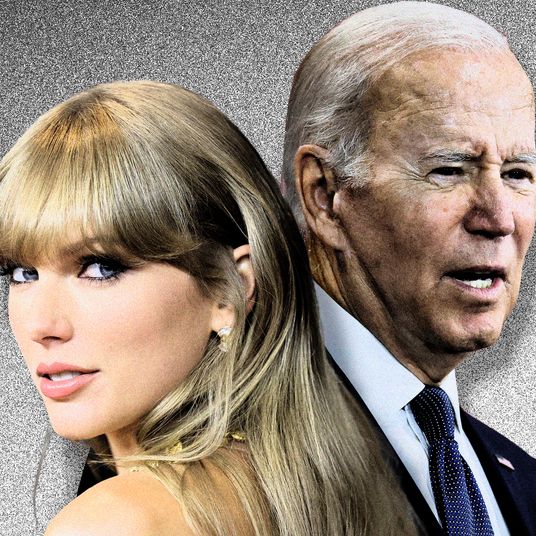

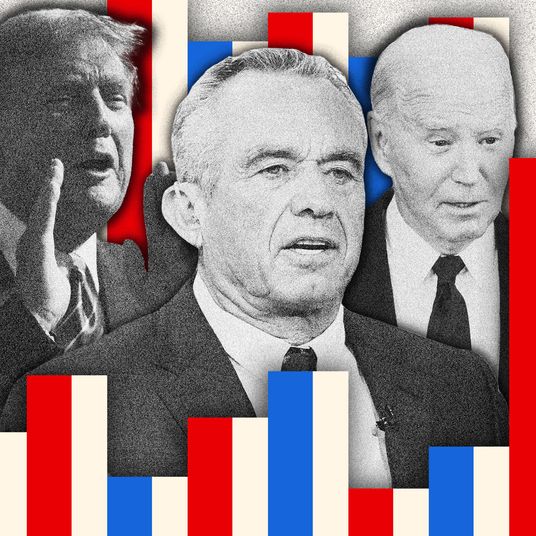

- Trump vs. Biden Polls: Will the War in Gaza Decide the 2024 Race?