- If the world hopes to achieve a negative carbon footprint, carbon sequestration will likely be a necessary tool in the green future toolbox.

- However, crystallization of captured carbon can take upwards of 7 to 10 years, which can allow some of that sequestered gas to escape.

- Scientists discovered bacteria capable of speeding up the mineralization process by a surprising amount, turning years into just a handful of days.

Although “net zero” is the goal of various international climate accords and government promises, to really curtail climate change’s impact means charging forward to a “carbon negative” world—one where the amount of carbon in the atmosphere is actually less than what is produced by human activity.

Obviously, you can’t just wish away carbon, so the next best idea is to take it out of the atmosphere. The leading candidate for locking away this unwanted CO2 is carbon sequestration, and while it’s often touted as some climate change cure-all (we most definitely need every clean energy source we can get, while also severely cutting emissions), the technology isn’t remotely ready to take on the global climate crisis. But the idea may be getting an ally from the most unlikely of places.

Researchers from the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology claim that a certain Geobacillus bacteria species increases the mineralization of CO2 when stored deep underground. Under ideal geologic conditions, crystallizing carbon dioxide takes 7 to 10 years. But this particular bacteria sped up the process to just 10 days using an enzyme called carbonic anhydrase. The researchers revealed the results of their study in December at the American Geophysical Union’s (AGU) annual conference in San Francisco.

Simply ejecting gas into the ground comes with its own mess of problems—for example, gas has a tendency to leak.

“When injected as a gas, CO2 has the potential to leak back to the atmosphere,” South Dakota Mines professor Gokce Ustunisik said in a press statement. “For example, if a geologic fault occurs or when there are changes in pressure following the initial pumping on the surface, stored gas will be looking for a way to escape.”

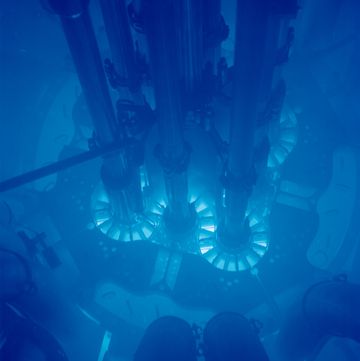

That’s why rapid mineralization of carbon would be a total game-changer—it would increase the amount that could be stored while also preventing any CO2 from escaping. The microbes responsible for this clever bit of rapid geology known as “carbon mineralization” were found 4,100 feet below the surface at the Sanford Underground Research Facility, located in a former Black Hills mining town in South Dakota.

In laboratory tests, scientists recreated the intense conditions found underground by tweaking temperatures, pressures, and salinities, according to New Scientist. What they found was that the microbe created a compound called carbonic anhydrase, and as the rock dissolved, it lowered acidity of the whole rock-and-CO2 solution so that the magnesium and calcium leftovers eventually form carbonate minerals.

“Surviving microbes would quickly convert the carbon dioxide into solid minerals in the pore space of the oil reservoir, providing permanent sequestration,” the researchers said in their December 2023 AGU abstract.

Who said the very big problems couldn’t be fixed with very small solutions?

Darren lives in Portland, has a cat, and writes/edits about sci-fi and how our world works. You can find his previous stuff at Gizmodo and Paste if you look hard enough.