Not so long ago, lawmakers and utilities were drunk on power — nuclear power. In the late 2000s, South Carolina legislators rewrote rules for building new nuclear reactors, shifting risks away from utilities and onto the backs of their customers.

Flush with this money, SCANA and Santee Cooper began work on two reactors 30 miles north of Columbia. As the years passed and the delays grew, SCANA executives told the public and shareholders that the project was going well.

It wasn’t, of course. Mismanagement and lax oversight had ignited a bonfire that torched $9 billion. Work on the reactors stopped, and criminal investigations began. It was South Carolina’s most expensive scandal, one that led to lawsuits, prison for some executives, lost jobs for others and the sale of SCANA to Virginia-based Dominion Energy.

But the hangover from this debacle is wearing off. Old and new energy players are rushing in. This time they’re pushing a plan to build a massive gas-fired generator at an old coal plant in the ACE Basin, coastal South Carolina's conservation jewel. A new gas pipeline would fuel the plant; the pipeline's route, size and price tag remain industry secrets.

Their playbook has echoes from the past. As they did for the nuclear project, power companies say that South Carolina is on the precipice of an energy crisis. As before, they argue their new plan will help them close dirtier coal plants. But there are new twists: Building a gas plant doesn’t carry the same construction risks as a nuclear reactor. And some of the strains on the grid are new, including a race to build energy-gulping data centers.

As they did before, state lawmakers also are trying to help. They’ve introduced bills to make it easier for power companies to condemn land. Language in one bill would even open a door to building more nuclear reactors. Another provision would defang the utility's regulators.

Tom Ervin, a member of one of those watchdog agencies, was so upset that he quit in protest. “South Carolina has been down this rocky road before,” Ervin wrote in his resignation letter.

And as before, conservation groups and public watchdogs are challenging the utilities’ plans and their cheerleading legislators. They say that utilities are gambling with ratepayers’ money by making billion-dollar bets on climate-harming fossil fuels while dishing out discounts to manufacturers and data centers — discounts unavailable to the public.

They say a large new pipeline project through the state carries its own set of risks, especially if it runs into opposition from landowners or cuts through environmentally sensitive areas.

And they say that the recent past is a powerful reminder about the consequences of bad choices and poor scrutiny, and how ratepayers often end up stuck paying for those mistakes.

This new push is "the most significant threat to energy bills, our environment and public participation that we’ve seen in over 25 years," said John Tynan, president of Conservation Voters of South Carolina. The group on March 20 launched a $150,000 ad campaign to oppose a bill Tynan said would "hand billion-dollar power companies a blank check.”

Seven years after news broke about South Carolina’s nuclear fiasco, this latest power play once again carries stakes that involve billions of dollars, climate change and the reliability of the electric grid.

A deeper look at these stakes and lessons of the past could begin in many places, but why not start in a lobby?

Closed doors

The South Carolina Statehouse lobby has stained glass, leather couches and mahogany doors. Looking up, you see the interior of the building’s dome, a kaleidoscope of browns and blues. During the session, lobbyists and lawmakers mill around a life-size statue of slavery apologist and former vice president John C. Calhoun. The lobby is an open place by design, where lobbyists mix with lawmakers, and school groups snake toward the chambers. But much of the real lawmaking occurs behind closed doors, as happened in 2007 when power companies needed a new law.

Nuclear reactors and their turbines can crank out large amounts of electricity without releasing greenhouse gasses. But they’re wildly expensive to build and they generate radioactive waste. Wary utilities focused on other power-generating sources, especially coal and natural gas.

Then, in the mid-2000s, Westinghouse and Toshiba touted new reactor designs they said were safer and faster to construct. They would use prefabricated parts, ship them to work sites and assemble them there. The technology looked good on paper, but the construction process hadn’t been tested in the field.

As in many states, South Carolina’s investor-owned power companies are regulated monopolies. When these utilities build generators, pipelines and transmission lines, they typically recover their costs from their customers and take a percentage as profits. In other words, the more they spend, the more they make. (Santee Cooper is a state-owned, not-for-profit utility.)

But erecting nuclear plants remained expensive and risky, risks that utilities didn’t want their shareholders to shoulder alone if something went wrong. So they turned to our elected officials.

One of those closed-door meetings in 2007 was in a conference room of Haynsworth Sinkler Boyd, a politically influential law firm that then had an office next to the Capitol grounds. The meeting’s host was Belton Ziegler, one of the firm’s lawyers at the time and former general counsel for SCANA. Zeigler had helped draft a new bill called the Base Load Review Act.

The meeting was supposed to be a chance for manufacturers to weigh in on the act. But some attendees recall Zeigler casting most of their suggestions aside.

“I can remember when we hit a brick wall, Belton would say 'I hear you,’ ” Scott Elliott, an attorney for the South Carolina Energy Users Committee, told The Post and Courier in 2017. Elliott took that “I hear you” as a polite way of saying the act’s language was already etched in stone.

Zeigler declined to comment for this story.

South Carolina lawmakers in 2007 quickly passed the Base Load Review Act, greased by thousands of dollars in utility campaign contributions. It began with the words: “An act to protect South Carolina ratepayers.”

Shifting the risks

At least 10 other states passed laws similar to the Base Load Review Act. It was a dramatic shift. In the past, utilities often borrowed money to pay for big-dollar infrastructure projects, much like a grocer taking out a loan to build a new store. But the Base Load Review Act and its ilk used financial tools to shovel more risks onto the backs of their customers.

These tools went by mind-numbing acronyms, such as ACR for “advanced cost recovery,” and CWIP, short for “construction work in progress.” The wonky language hid their power: These tools were magic wands that allowed electric utilities to bill their customers as they designed and erected new power plants. It was akin to paying a grocer as it built a new store with the hope that the company would charge less for groceries in the future.

Power companies said these cost recovery tools would save customers money in the long run by lowering overall borrowing costs. In practice, utilities here and across the nation began to set their customers’ money on fire.

Mississippi Power tried to build a “clean coal” natural gas plant in rural Kemper County with technology designed to capture carbon dioxide. Power bills rose 15 percent in 2015 as delays and costs ballooned. The utility eventually lost more than $6.4 billion before scrapping the project altogether.

In Ohio, federal officials arrested the state’s House speaker on charges he sought $60 million in bribes to help pass a $1.3 billion bailout for two nuclear plants. In sentencing the lawmaker to 20 years, a judge said: “You were not serving the people. You were serving yourself.”

Near Augusta, Georgia Power’s Vogtle nuclear reactors took more than 14 years and $35 billion to build and are only now coming online. The project will add 10 percent to an average customer’s monthly bill.

Closer to home, SCANA executives tried to hide delays and growing costs for the V.C. Summer nuclear project. But the problems were too large to cover up. When the utilities pulled the plug, SCANA’s 700,000 customers had already ponied up more than $2 billion for a project that would never generate a watt. The failure would cost Santee Cooper customers an extra $13 a month for four decades, an executive would later tell The Post and Courier.

Two top SCANA executives pleaded guilty to federal fraud charges in a crime that created a “nuclear ghost town,” then-acting U.S. Attorney Rhett DeHart said. Facing shareholder lawsuits, SCANA sold its company to Dominion, a utility based in Virginia. The head of Santee Cooper lost his job amid calls to sell Santee Cooper outright.

Burned, South Carolina lawmakers in 2018 repealed the Base Load Review Act. They strengthened the South Carolina Public Service Commission, the agency that regulates the state’s utilities.

For a moment, the balance of power had tilted back toward the public.

Dominion Energy system control room near Columbia.

Wakeup call

The jet stream is a powerful river of air that shoots across the United States, determining much of our weather in the process. Its undulations can push cold air south or pull warmer air north. Scientists have posited that a rapidly warming planet causes these undulations to swing even more deeply. Just before Christmas in 2022, the jet stream dipped sharply south. Arctic air swept across the South, pushing utilities’ grids to the breaking point, and then past it.

Power plants across the nation buckled. Freezing temperatures triggered mechanical failures — more than 1,700 generating units and associated infrastructure. Nearly half of those failing elements involved natural gas generation and transmission, a federal report found. In the Carolinas, about 500,000 customers in North Carolina and 100,000 customers in South Carolina temporarily lost power. It was a massive failure of the nation's natural gas infrastructure, and it's unclear whether an additional gas plant in the Lowcountry would have made a difference that Christmas, but utility officials cite it as a wakeup call.

“This happened in areas that had a lot of growth — Georgia, North Carolina and South Carolina — and all of those areas were cold at the same time,” said Michael Couick, chief executive officer of the Electric Cooperatives of South Carolina, a group that represents 18 consumer-owned electric utilities. “We were lucky that it happened on a Christmas vacation day when schools and industry were closed.”

Dominion’s control facility near Columbia is another place to experience the dance utilities do to keep power on. Through a guard gate and past metal detectors, you enter a cavernous room. Its black walls frame a curving array of maps and monitors and blinking lights. From this nerve center, workers tweak a large part of South Carolina’s electric grid.

Electrical towers at the site of a proposed gas plant at the old Canadys coal-plant on March 18, 2024.

Dominion has approximately 5,604 megawatt hours of dispatchable power in South Carolina at any given time. Some comes from coal, a reliable source of electricity that also generates enormous amounts of pollution and greenhouse gases. As coal costs grew, utilities across the country converted plants to natural gas or shuttered them, and Dominion is part of that trend. It plans to convert two coal units into ones fueled by natural gas by 2028. Two other units, the Wateree station in Richland County and Williams station in Berkeley County, are scheduled for closure in 2030. Meantime, the utility added 40,000 new accounts since taking over SCANA's business five years ago.

The utility has few other options than natural gas to meet the grid’s demands, Dominion South Carolina President Keller Kissam said during a recent walk-through. At times, more than 40 percent of the utility’s power comes from solar panels, but Dominion reaches that number only when the sun is shining. Dominion had no solar power available during the Christmas 2022 crisis, he said. As Kissam spoke, rain fell across South Carolina, and the room’s monitors showed solar power levels fluctuating.

Engineers also can flip switches to tweak the grid's hydroelectric generators. When consumers are using less energy, engineers can pump water from a low reservoir to a higher one. Then, during heavy demand, they can release the water, generating a 600-megawatt swing in just 15 minutes. But building new hydropower also faces a daunting set of approvals.

This balancing act has grown more difficult amid the proliferation of new data centers, cryptocurrency miners, manufacturing and the move toward electric vehicles, utility officials and energy experts say.

A large data center can use as much electricity as 80,000 households, a recent McKinsey report said. In 2022, the country's 2,700 data centers used about 4 percent of the nation's electricity. By 2024, those centers will use 6 percent of the country's electric generation, the International Energy Agency said.

Cryptocurrency mining factories also use enormous amounts of energy, enough power in some cases to power 10,000 homes. South Carolina has seen announcements of a half-dozen new Bitcoin mining centers in the Upstate during the past three years. Worldwide, capital spending to meet these growing energy demands will increase from $2.8 trillion to $4 trillion in 2030, the International Energy Agency said.

Locally, some of this spending could happen 80 miles south of Dominion's Columbia nerve center, along the banks of the Edisto River.

Future gas plant?

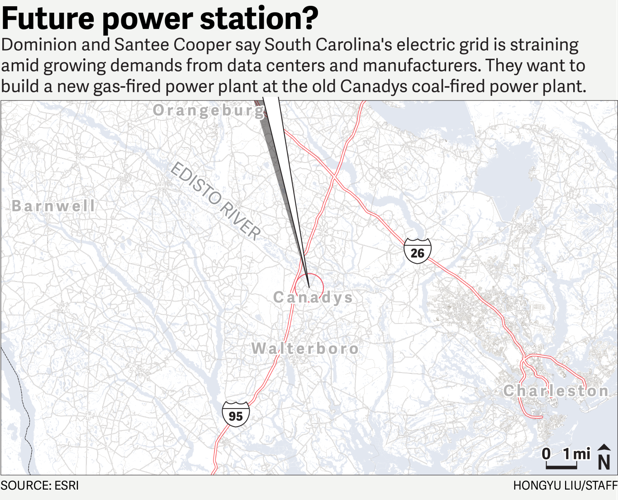

Dominion’s Canadys site sits on the Edisto in a swampy area next to Colleton State Park. For decades, a coal-fired power plant pumped out electricity. Today that plant is closed, but with lawmakers’ help, Dominion and Santee Cooper hope to build a massive gas-fired power station there.

Dominion said the Canadys site makes sense because it owns the land and has existing transmission lines and substations nearby. (Another contending site in Hampton County is closer to large gas lines. But Santee Cooper has said it prefers the Canadys site.)

Future power station?: Dominion and Santee Cooper said South Carolina’s electric grid is straining amid growing demands from data centers and manufacturers. They want to build a new gas-fired power plant at the old Canadys coal-fired power plant. A new pipeline would need to be built, with two potential connections near Savannah and Augusta. (Source: Esri)

In Canadys, a small natural gas pipeline runs to the area, but the utility would need a much larger one. Interstate pipelines can be 2 to 3 feet in diameter and require a roughly 100-foot-wide path for construction. Existing supply junctions are near Savannah and Augusta, but the utilities have yet to spell out how large the pipeline will be and where in South Carolina it will go.

The lack of information worries conservation groups, who fear a large new pipeline could affect the ACE Basin, an estuary of three Lowcountry rivers that has long been celebrated for protecting large expanses of public and private property.

"Pipeline projects destroy habitat, harm local wildlife, damage air and water quality, put people at risk of explosions and leaks, and threaten our private property rights," said Kate Mixson, senior attorney for the Southern Environmental Law Center.

The gas plant itself would be a “combined cycle” generator, which uses excess heat to produce more power than earlier designs. During 2022 and 2023, 13 combined cycle plants went online, the U.S. Energy Information Administration said. Such plants pollute much less than coal-fired units but still generate carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas. Dominion and Santee Cooper have said the Canadys plant could generate upwards of 2,000 megawatts, rivaling what the failed V.C. Summer nuclear project would have cranked out.

Neither Dominion nor Santee Cooper have put a price tag on the plant or the pipeline, though industry and government estimates show a gas plant that size typically costs at least $2 billion.

CO2 level in atmosphere on the rise

425

400

Mean CO2 Levels (ppm)

375

350

325

1960

1980

2000

2020

SOURCE: NOAA.GOV

HONGYU LIU/STAFF

CO2 level in atmosphere on the rise

425

400

Mean CO2 Levels (ppm)

375

350

325

1960

1980

2000

2020

SOURCE: NOAA.GOV

HONGYU LIU/STAFF

Construction of gas plants carry much fewer risks than nuclear reactors. But powering turbines with natural gas carries long-term perils, especially if gas prices rise or government restrictions on carbon dioxide grow stiffer. Dominion and Santee Cooper have acknowledged these risks, but they don’t exactly highlight them in their public planning documents.

In Santee Cooper’s 236-master energy plan, the utility said ratepayers could be on the hook for an extra $2.8 billion if natural gas prices rise. If utilities end up paying for carbon dioxide emissions, a plausible scenario given the planet’s climate emergency, ratepayers could get smacked by an additional $14 billion.

Despite the risks, state lawmakers are rushing in to help the utilities build the gas plant — and more.

In this case, the bill is called “South Carolina Ten-Year Energy Transformation Act.”

Base Load 2.0?

Among its many provisions, the bill would reduce the number of S.C. Public Service Commissioners from seven to three. It would open the door to building small modular nuclear reactors. And if the utilities decide to abandon a nuclear project, they must provide a “fulsome accounting” of the costs — language that had critics scratching their heads about how "fulsome" might be defined.

Early versions of the bill required regulators to give more weight to what utilities said about their plans than the public. The bill also would make it easier for utilities to build new pipelines.

"This bill puts the state government in the pipeline business, not only across sensitive wetlands and the Edisto River, but potentially all over the state," said Eddy Moore of the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy, adding that lawmakers are poised to vote on a bill even though they don't know where the plant and pipeline will go, how much it will cost and whose land might be taken.

As the Base Load Review Act did in 2007, the new bill is moving quickly through a legislature that once spent five months arguing about whether to name the right whale or bottlenose dolphin the state marine mammal.

As they did before the V.C. Summer debacle, power companies ramped up their lobbying. Dominion, Santee Cooper and Duke Energy spent more than $2.6 million to lobby state lawmakers during the past three years, public filings show.

Unlike 2007, some are warning about the speed of the process and the decrease in public scrutiny implicit in the bill's language.

Tom Ervin, a former circuit court judge, saw what was happening and quit his post on the South Carolina Public Service Commission.

In a blistering letter on March 13 to lawmakers, Ervin said the new bill would gut regulators of their hard-earned expertise, open the door to back-room deals and give utilities “a blank check with guaranteed profits, resulting in much higher utility rates for residential customers.”

He suggested that the General Assembly put a temporary freeze on energy-hogging data centers and crypto-mining operations. He noted that a new natural gas pipeline would carry all sorts of potential risks that could leave ratepayers on the hook for billions of dollars.

“There are simply too many unanswered questions and concerns that need to be addressed,” he wrote.

Electrical power lines are seen along Highway 61 near the site of the new Dominion and Santee Cooper gas plant at the old Canadys coal plant on March 18, 2024.

Rerun?

Away from the Statehouse lobby, in the bowels of a nearby office building, House lawmakers held hearings about the bill.

Pro-power plant representatives spoke about the vulnerability of the state’s electric grid and South Carolina’s booming economy. But most speakers opposed the bill.

Most opponents said they supported more energy production, but not if it meant weakening the public’s ability to regulate monopoly utilities. Or foregoing harder looks at solar power and other climate-friendly sources.

House lawmakers tweaked the bill but left much of the language intact as it moved through a committee. At one point, John Brooker, energy policy director for the Conservation Voters of South Carolina, asked a question that went to the heart of the issue: If the gas plant plan is the most cost-effective way to meet the state’s energy challenges, why do utilities need to undermine regulators? “Why can’t it stand on its own merits?”

As they did in 2007, lawmakers over the next few months will cut through the Statehouse lobby. They'll head to chambers and committee rooms, reworking how South Carolina builds new power plants — and how the public might weigh in.

And as happened in 2007, their work could ripple through the grid and ratepayers' pocketbooks for a generation.

Dominion and Santee Cooper hope to build a new gas plant at the old Canadys coal plant. Trucks are seen entering the facility on March 18, 2024.

John McDermott and David Wren contributed to this report.