There is a basic problem with discussions of Henry David Thoreau, an issue that ails accounts of every Famous Writer but that is particularly acute with him. It is the idea—the lie, really—that he knew what he was doing. Thoreau’s canonical status in American culture—the fact that he’s assigned in school, or that Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. found inspiration in his work—gives the impression that we can take his ideas down and admire them whole, like a fine ashtray. Thoreau, it seems, wanted to be seen as a secular sage, strove to live his life as a work of art. But out of kindness to him and ourselves, we should decline to play along. Thoreau was a resident of the greater Boston area, who made wrong turns, who sent cranky letters to his editor, and who got awkward when someone had an unwanted crush on him. By seeing him as more-than-a-person, we miss out on one of the biggest questions about him, an argument that has been ongoing since his early 20s. It is this: Was Henry a genius and a saint, or was he very annoying?

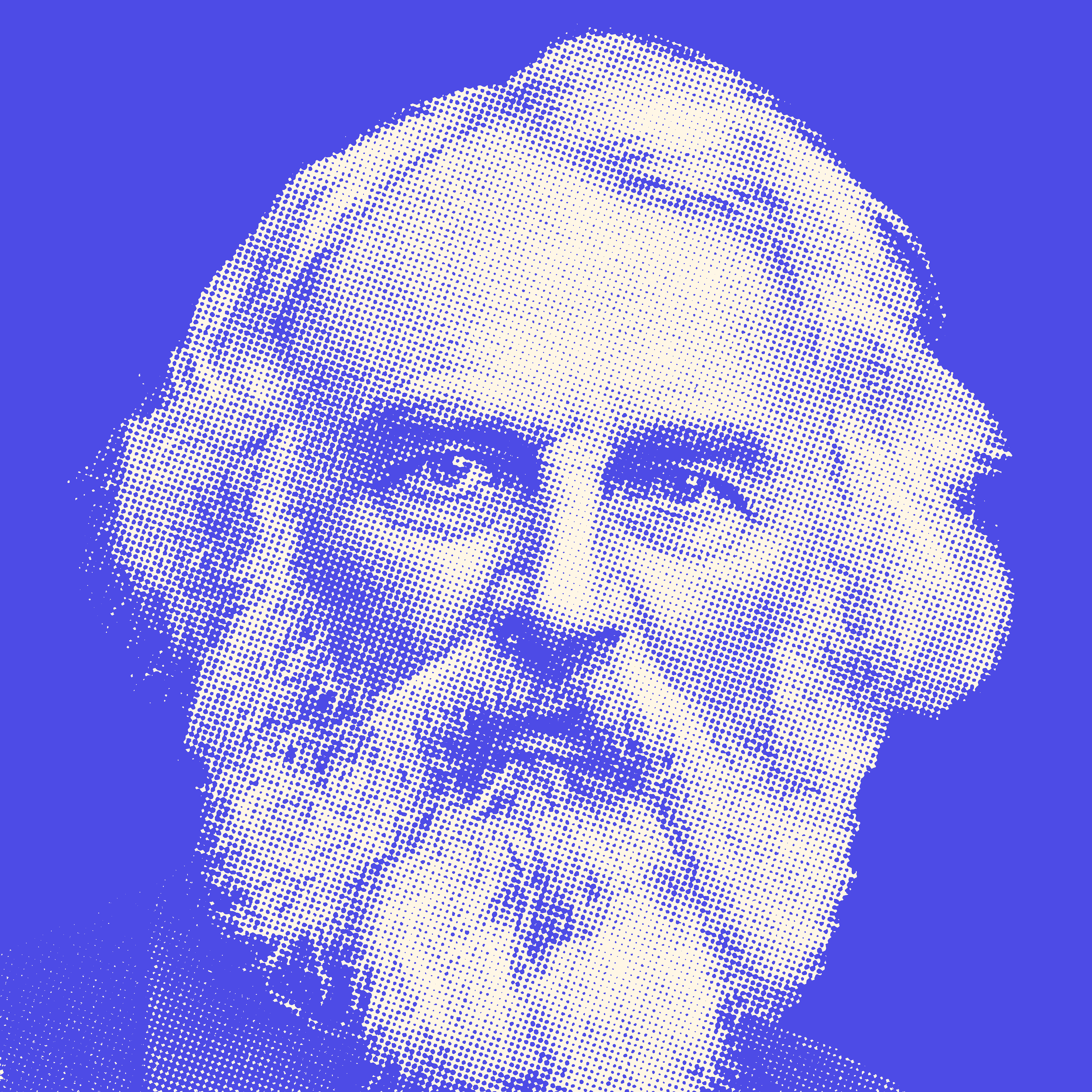

He was born in 1817 in Concord, Massachusetts, son of a pencil-maker. A happy moment to be a free American: The country was victorious after the War of 1812, and Massachusetts one of its economic engines. Harvard-educated. While still a student, he meets Ralph Waldo Emerson, 14 years his senior and already an icon, who became a kind of stand-in father. At 24, he moves in with the Emersons. At 27, he moves to Walden Pond. (His mother keeps doing his laundry.) His first book, published at age 32, fails. His second, Walden, published at 37, is a success. It is now 1854. He is a writer in his own right. And now the drama starts.

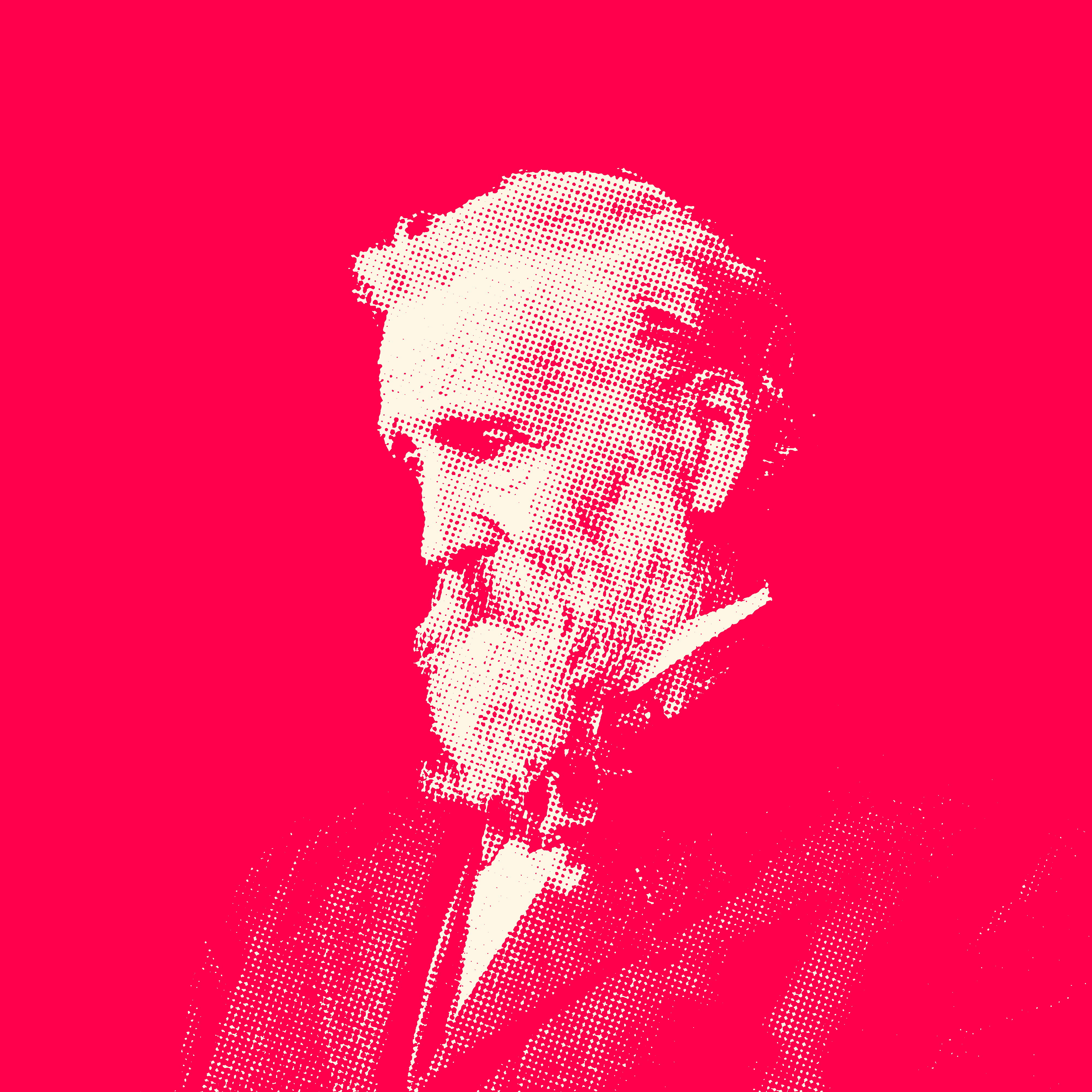

The Atlantic was founded in 1857. James Russell Lowell, the magazine’s first editor, soon asks Thoreau to submit something. The two men have a history. About a decade earlier, Lowell wrote a poem that ridiculed Thoreau’s height and implied that he was just a knockoff of his mentor:

There comes [Thoreau], for instance; to see him’s rare sport,

Tread in Emerson’s tracks with legs painfully short;

Yet Thoreau gamely submits an account of his time in the Maine woods. Lowell runs it, but cuts a worshipful sentence about an evergreen tree. (The sentence has been restored online.) Outraged, Thoreau swears that he’ll never write for the magazine as long as Lowell edits it.

He didn’t have that chance. Thoreau died of tuberculosis in 1862, a year after Lowell left his post. But now Emerson steps in. He writes a startlingly honest eulogy for his friend, which The Atlantic runs; it also publishes “Walking,” one of Thoreau’s finest essays. From then on, the magazine, which barely published Thoreau while he was alive, championed him as “one of their own,” the literary scholar Daniel A. Wells writes. It excerpted his posthumous books, rushed extracts of his journals to print. By the end of the century, writers were grumbling about “the cult of Thoreau,” but The Atlantic was arranging pilgrimages to Walden Pond.

Lowell, meanwhile, became Thoreau’s biggest critic. “We look upon a great deal of the modern sentimentalism about Nature as a mark of disease,” he wrote in the rival North American Review, of which he was now the editor. “To a healthy mind, the world is a constant challenge of opportunity. Mr. Thoreau had not a healthy mind.” The Review attacked Thoreau as a tedious egotist for the next half century.

To some degree, that old fight persists. In 2015, Kathryn Schulz outlined Thoreau’s bore-ish traits in The New Yorker; Jedediah Britton-Purdy, a Columbia law professor, defended him in The Atlantic.

Who was right? Well, look. He does not seem to have been a very fun hang. In his eulogy for Thoreau, Emerson wrote that young men, experiencing what we would now call a quarter-life crisis, would meet him and realize that this utter weirdo had it, the sense of purpose they had been craving: “This was the man they were in search of, the man of men, who could tell them all they should do.” As soon as they got that look in their face, Thoreau shut down. He would ignore them at the dinner table, decline their invitations to go walking. He turned down free trips to the Yellowstone River and South America, Emerson reported, out of aloofness.

This is, remember, how Thoreau was described by a close friend in a eulogy. But the men had it good by comparison. With a few significant exceptions, Thoreau found women boring, feeble, and “an army of non-producers.” (Incredible criticism from a man who, by his own account, took four-hour hikes every day.) “It requires nothing less than a chivalric feeling to sustain a conversation with a lady,” he journaled. Some scholars have chalked this antipathy up to a confused homosexuality; he was, at the very least, flummoxed by his own body his entire life.

Aloof, irritable, misogynist—yes, so, why read Thoreau? There are two reasons. The first is that he arrived at the right answer on the greatest moral crisis of his time: He knew that chattel slavery, then essential to the American economy, was a crime against humanity, and he knew that violence was permissible to tear it down. And the second is that he had one exemplary skill: He was a writer. He put his eyes on the world, and that lonely, pure, hypocritical dynamo of a mind spat out insight, asides, quips, profundities. He excels as a writer of attention, of experience, of the thoughts that flicker across our mind on long walks or long drives before vanishing forever. He captured what it’s like to live from moment to moment—which is to say, what it’s like to live.

Take the final cascade of images at the end of “Walking.” He is on one of his hours-long walks through a local farm. The stroll has taken him into the late afternoon. “I saw the setting sun lighting up the opposite side of a stately pine wood,” he reports. “Its golden rays straggled into the aisles of the wood as into some noble hall.”

And suddenly, he is in that hall. He has walked into an ancient mansion, owned by an invisible family, “admirable and shining,” that had lived in Concord for centuries. “The pines furnished them with gables as they grew. Their house was not obvious to vision; the trees grew through it. I do not know whether I heard the sounds of a suppressed hilarity or not. They seemed to recline on the sunbeams. They have sons and daughters. They are quite well.”

His attention caresses the world, enchants it. We are there with him, aside that eternal family in that sun-kissed hall. But Henry is too honest to leave us on that daydream. The world is always a little more disappointing than we want. So he shares what happened next: He forgot about the whole thing. “It is only after a long and serious effort to recollect my best thoughts that I become again aware of [the family’s] cohabitancy,” he admits. “They fade irrevocably out of my mind even now while I speak.”

Thoreau was independent, aggrieved, motivated by a highly idiosyncratic sense of aesthetics and a full-body adoration of liberty. He resented his neighbors but loved humanity. He was excruciatingly American of a certain type: He is the forefather of UFOlogists, Appalachian Trail thru-hikers, effective altruists, and minimalist UX designers. He would have loved open-source software. Like certain libertarians and Communists, he married a hatred of everyday political intercourse with an absolute optimism about the future and an unshakeable faith in the ultimate goodness of humanity.

On the one hand, that hopefulness, that trust in other people and mistrust in institutions, is the bedrock of democracy. On the other hand, it is ripe for abuse and appropriation; there is currently a Mazda commercial that quotes him. But “Walking” gives us a sense of where he drew that hope: from novelty, from growth, and from expansion—imperial or otherwise. (Despite revering the wisdom of America’s Indigenous population, whole swaths of “Walking” treat their genocide as inevitable.) Although he never went to California, he would have loved the Californian ideology. But unlike advertising—unlike the politicians he loathed, and unlike all of us on the internet, every day—he did not lie. A saintly trait, that.