Pew Research Center has been tracking restrictions on religion around the world since 2007. We divide these restrictions into two categories: actions by governments and actions by private individuals or groups. Our tally of restrictions includes laws that prohibit atheism, as well as attempts to coerce people into adopting religious beliefs.

This post is based on the 14th annual Pew Research Center report on the extent to which governments and societies around the world impinge on religious beliefs and practices. The studies are part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project, which analyzes religious change and its impact on societies around the world.

To measure global restrictions on religion in 2021, the most recent year for which data is available, the study rates 198 countries and territories by their levels of government restrictions on religion and social hostilities involving religion. The new study is based on the same 10-point indexes used in the previous studies.

- The Government Restrictions Index (GRI) measures government laws, policies and actions that restrict religious beliefs and practices. The GRI comprises 20 measures of restrictions, including efforts by governments to ban particular faiths, prohibit conversion, limit preaching or give preferential treatment to one or more religious groups.

- The Social Hostilities Index (SHI) measures acts of religious hostility by private individuals, organizations or groups in society. This includes religion-related armed conflict or terrorism, mob or sectarian violence, harassment over attire for religious reasons and other forms of religion-related intimidation or abuse. The SHI includes 13 measures of social hostilities.

To track these indicators of government restrictions and social hostilities, researchers combed through more than a dozen publicly available, widely cited sources of information, including the U.S. Department of State’s annual Reports on International Religious Freedom and annual reports from the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, as well as reports and databases from a variety of European and United Nations bodies and several independent, nongovernmental organizations. (Read the methodology for more details on sources used in the study.)

Our latest study, the 14th in this annual series, covers events that took place in 198 countries and territories in 2021. Here are the key findings:

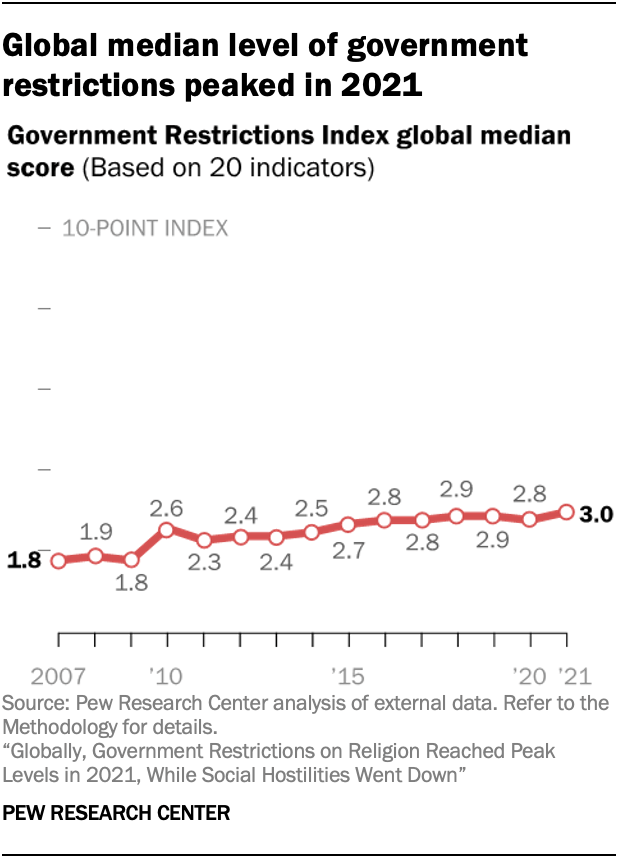

Government restrictions on religion reached a new high in 2021. Globally, the median score on our 10-point Government Restrictions Index rose from 2.8 in 2020 to 3.0 in 2021 – the highest level recorded since we began tracking this in 2007. The index tracks 20 measures on government laws, policies and actions that limit religious beliefs and practices, including banning certain faiths; the use of force against religious groups; preferential treatment of some groups over others; and restrictions on preaching, converting or proselytizing.

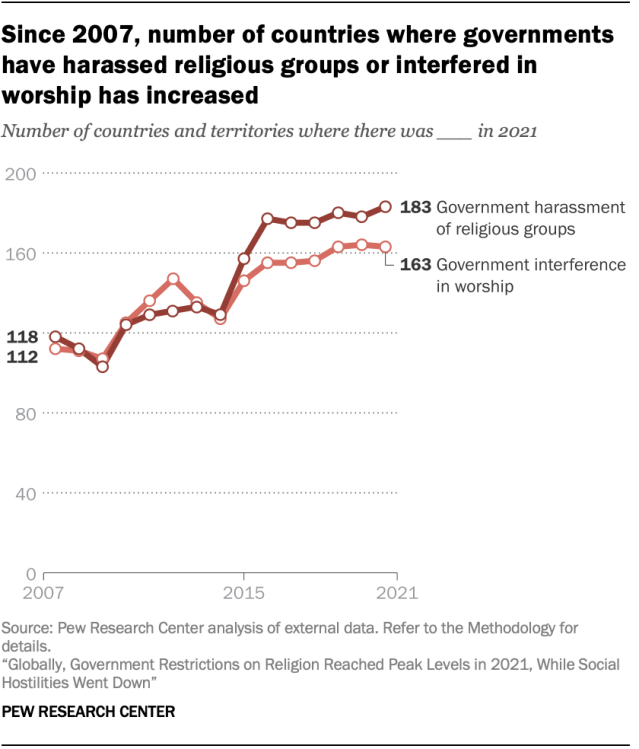

The most common kinds of government restrictions on religion in 2021 included harassment of religious groups and interference in worship. Governments harassed religious groups in 183 countries, the most on record. The harassment took a wide range of forms, from the use of physical force to derogatory comments made by public officials.

In Nicaragua, for example, top public officials verbally attacked Catholic clergy for supporting pro-democracy protestors. The president and vice president, who is also the first lady, called Catholic priests and bishops “terrorists in cassocks” and “coup-plotters.” A member of the National Assembly, Wilfredo Navarro Moreira, also called a cardinal and several bishops “servants of the devil” in a television interview.

Meanwhile, governments interfered in worship in 163 countries, very close to the peak level of 164 countries reached in 2020. Government interference in worship includes policies or actions that disrupt religious gatherings, deny permits for religious activities, bar access to places of worship, and restrict other rituals.

Some cases of government interference in worship in 2021 were related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

For example, three Canadian churches faced government fines for defying lockdown measures, prompting them to file a legal challenge on the grounds that other entities – including restaurants, other businesses and Orthodox Jewish congregations – faced fewer restrictions. In addition, several Canadian clergy faced arrest and fines after holding in-person services in violation of public health measures.

(It’s important to note that our study does not attempt to determine whether particular restrictions are justified or unjustified. Nor do we attempt to analyze the many reasons why restrictions may have arisen in each country. The goal of the tracking is simply to measure restrictions in a transparent and reproducible way, and to identify patterns and trends over time.)

In 2021, China had the world’s highest level of government restrictions on religion, while Nigeria had the highest level of social hostilities involving religion. Social hostilities are actions by private groups or individuals that infringe on the freedom of religious groups.

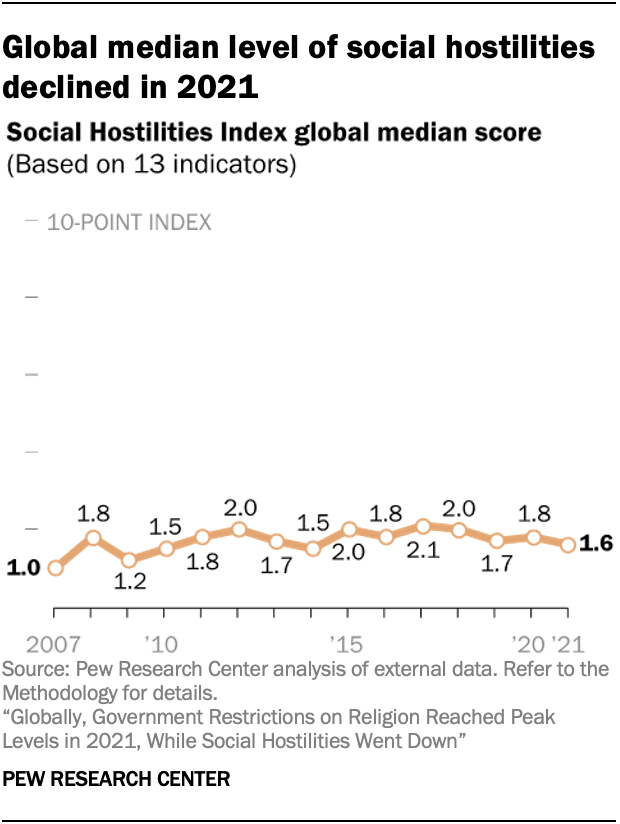

Globally, social hostilities declined slightly in 2021, with the median score on our Social Hostilities Index falling from 1.8 in 2020 to 1.6. In general, social hostilities have tended to fluctuate more than government restrictions from year to year. But some hostilities also have become deeply entrenched.

In Nigeria, for example, “intercommunal clashes” took place between predominantly Christian farmers and Muslim herders, driven largely by competition for land and natural resources. Both groups have formed armed factions. In August 2021, ethnic Irigwe Christians in Nigeria reportedly killed 27 people and injured 14 when they attacked five buses transporting Muslims across Plateau State, in the North Central part of the country. The following month, Muslim herdsmen reportedly killed 49 people and kidnapped 27 – mostly Christians – in the neighboring state of Kaduna.

Nigeria also experienced continued violence by Boko Haram and Islamic State militants throughout 2021.

Governments in 161 countries provided benefits to religious groups in 2021, even as government officials in most of these countries also carried out harassment (149 countries) or interfered in worship (134 countries). A new feature of our latest report is an attempt to count how many governments provide benefits to religious groups while, at the same time, harassing religious groups or interfering in their worship.

One of the most common benefits that governments provide is support for religious education. We identified 127 countries that provided this kind of support in 2021, as well as 107 that supported religious properties (such as funds to build or maintain houses of worship) and 67 that provided benefits to clergy (such as payment of salaries).

For example, in Saudi Arabia, where Sunni Muslims comprise the majority of the population, the government funds the construction of most Sunni mosques and gives a monthly stipend to imams. At the same time, the country’s Ministry of Islamic Affairs prescribes a list of approved themes for sermons in mosques and forbids messages that are deemed “sectarian, political, or extremist,” according to the U.S. State Department. Clerics also have been targeted when their religious views go against what is considered acceptable by the government. In 2021, a Sunni cleric named Hassan Farhan al-Maliki remained in prison without due process for “allegedly calling into question the fundamentals of Islam,” according to the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom. The cleric has been in prison since 2017.

For more information on government restrictions and social hostilities involving religion in other countries, read the full report here.