Predictors of Outcome and Recovery

Multiple reports suggest that 80% to 90% of infants with BPI recover spontaneously by 3 months of life.[18,19] Numerous factors should be considered when presenting optimistic outcomes to parents of infants with BPI, including the type and site of the specific BPI, the natural history of injury recovery, any developmental factors, and the presence of residual deficits.

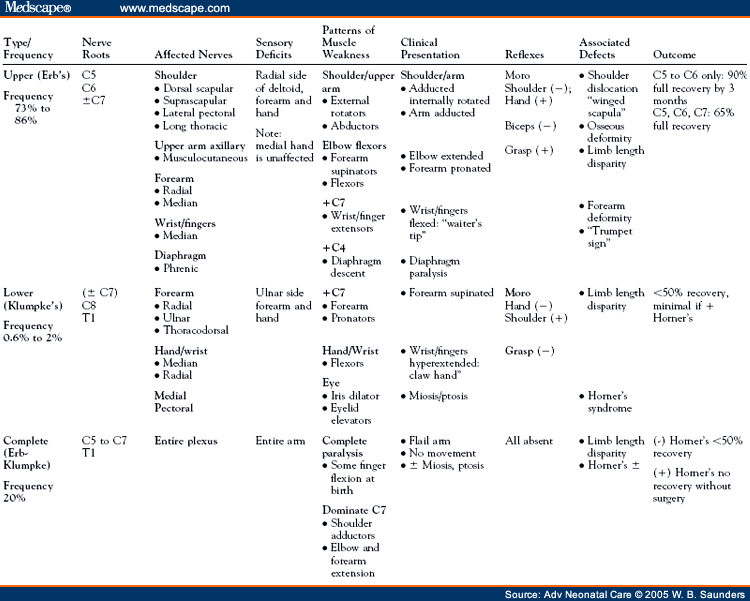

The definition of a good recovery varies significantly in the literature. Some authors consider a "good recovery" as 50% of normal ROM whereas others aim for full restoration of complete motor and sensory function in all affected muscles.[10,36] Recovery of C5 to C7 function within the first month of life and absence of secondary shoulder abnormalities are both associated with favorable outcomes.[5] Predictors of poor outcomes include increased birth weight (>90th percentile), lack of elbow flexion at 3 months, C7 nerve root involvement, complete C5 to T1 injury, and the presence of Horner's syndrome.[26,28,37,38]

Proximity of the injury to the nerve root affects recovery. Nerve regeneration occurs at a pace of 1 inch per month.[11] A long distance between the site of nerve injury (nerve root/trunk) and its target muscle Results in longer periods of denervation and incomplete recovery. Denervation of muscles supplied by proximal nerves (i.e., supracapular nerve-to-rhomboid muscle) implies a more severe injury and probably nerve root avulsion with a poor prognosis.[14] The C8 to T1 nerve roots are less secure and more prone to separation from the spinal cord with traction forces. Horner's syndrome with avulsion of the C8 to T1 nerve root proximal to the spinal ganglion indicates a more severe injury and poor prognosis for motor function recovery.[38] Complete brachial plexus injuries are twice as likely as upper root injuries to result in permanent paralysis.[25] Upper root injuries are the most likely to recover, although residual deficits of shoulder and forearm deformities may persist.[36]

Recovery from BPI can be broadly categorized into 3 categories: early and complete (within 3 weeks), early with residual deficits, and incomplete. Most brachial plexus lesions that will recover completely do so within 3 weeks. Recoveries after 3 weeks may be complete; however, some infants may have residual deficits and require secondary surgeries.[7]

Understanding the true natural history of recovery from the literature is complicated by differences in study designs. The initial presentation of BPI is similar in various reports, the extent of severity can only be identified over time. Reports of full functional recovery should include sufficient time to assess the increasingly complex range of daily activities that develop from infancy to early childhood. Studies that do not extend follow-up to 3 years may miss residual deficits. Retrospective reports of select patient cohorts, such as those referred to specialty clinics, may be biased to the most severe injuries and underreport spontaneous recovery. Differences in motor strength grading tools can further complicate comparisons of functional recovery.[39]

The natural history of BPI in untreated infants from 1966 to 2001 was analyzed by a systematic review of the literature. The most rigorous studies in this series reported that 20% to 30% of BPI cases had functional residual deficits.[39] A Swedish study found residual defects of ROM and grip strength in 66% of children with BPI at 5 years of age, including those fully recovered.[40]

Nerve regeneration is generally more successful in young infants. Animal models suggest that neonatal motor neurons are more sensitive to the regenerative effects of neural growth factors.[41] Incomplete or partial peripheral nerve recovery is generally thought to be due to lack of nerve regeneration and is detectable by EMG. In some cases, a functional disability persists despite EMG evidence of positive motor nerve regeneration. This lack of recovery in an apparently reinervated muscle group may be due to a defect in central motor programming during a critical period in development. It is theorized that a "developmental apraxia" Results when paralysis in the first months of life interferes with visual- and sensory-guided tasks such as reaching and grasping.[42] Central nervous system plasticity and remodeling may be more successful in reprogramming sensory input, as evidenced by the switch in dominance from the affected to unaffected extremity. Infants do not seem to develop the chronic pain or neuropathies seen with adults. Acute pain responses, however, are present and evident during activities such as physical therapy.[34]

Progressive changes in muscle fibers begin within 1 week after a degenerative injury. Muscle tissue becomes fibrotic and, by 3 years, it atrophies, with scar tissue and fat replacing muscle tissue.[43] Developing bones are susceptible to mechanical stresses. Shoulder contraction from chronic internal rotation of the shoulder and humeral head deformity are sequelae in >50% of infants with BPI, including those with complete neurological recovery and physical therapy. These defects occur within 6 months of injury.[7] Limb-length disparities are more severe in complete BPI. They can occur, however, with all types of lesions.[44] A winged-scapula defect is a result of paralysis of the long thoracic nerve (origin C5 to C7) as the scapula is no longer held to the chest wall muscles and protrudes away from the back.[45] Physical deformities such as a "winged-scapula" and "trumpet sign" result from the constant muscle imbalance and contractures of unopposed muscle groups (Fig 7).[22] Behavioral and developmental problems have been reported in children with BPI, possibly due to stress and self-consciousness from their functional and physical disabilities.[46]

"Trumpet posture" is the result of shoulder contractures in upper plexus injuries. Note how bringing the affected hand to mouth resembles the position of a bugler. Adapted and reprinted with permission. Dodds SD, Wolfe SW. Perinatal brachial plexus palsy. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2000;12:40-47.

Adv Neonatal Care. 2005;5(5):240-251. © 2005 W.B. Saunders

Although Dr. Nath does not agree with all of the concepts brought forth in these articles, he has graciously allowed the use of these excellent teaching tools to further educate the medical community on BPI.

Cite this: Part 2. Distinguishing Physical Characteristics and Management of Brachial Plexus Injuries - Medscape - Oct 01, 2005.

Comments