Everything To Know About NASA's Lucy Spacecraft And Its Mission

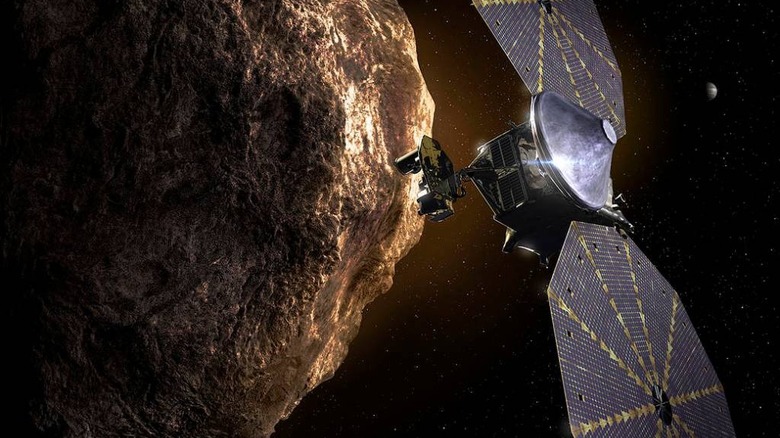

In 2021, NASA successfully launched the Lucy mission, sending the unmanned spacecraft to visit a group of asteroids called the Trojans. Researchers hope these asteroids, located in the orbit of Jupiter, can answer questions about the early stages of our solar system.

It's a long journey from Earth to Jupiter; Lucy isn't expected to arrive at the Trojans until 2027. It has already been busy, however: Lucy has already taken measurements of one asteroid on its way to Jupiter and will do the same with another before reaching the eight Trojan asteroids for its primary mission. Those measurements include surface geology, interior composition, whether the asteroids have craters on their surfaces, and if they contain significant compounds like rare minerals or water ice.

In the few years it has been traveling, Lucy has already made exciting discoveries. Many of Lucy's finds weren't even part of the probe's original mission, answering old questions and uncovering new mysteries.

Lucy's discoveries so far

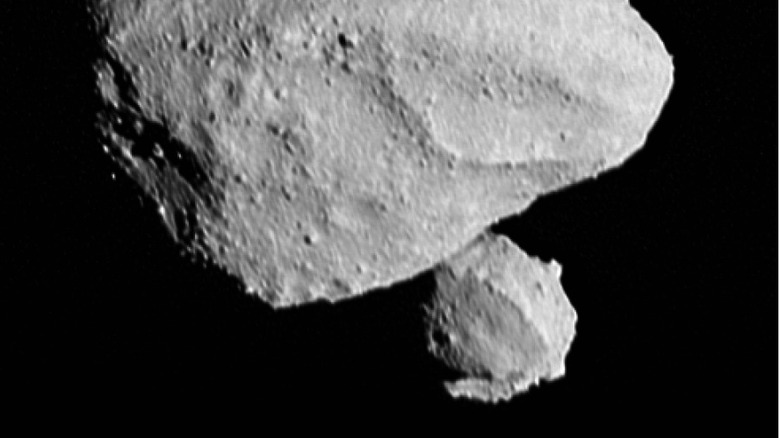

Lucy made its first flyby of an asteroid in 2023, when it passed by an asteroid called Dinkinesh. Dinkinesh is tiny, just 800 meters across, making it an excellent test subject for Lucy's instruments. The data collected will reveal how well Lucy can study small objects with unpredictable trajectories.

When the team turned their instruments on Dinkinesh, they found a surprise. What they originally thought to be a second, smaller asteroid orbiting Dinkinesh turned out to be a contact binary:two separate objects touching each other. That had never been observed on an asteroid.

"It is puzzling, to say the least," said Lucy's principal investigator, Hal Levison of the Southwest Research Institute. "I would have never expected a system that looks like this. In particular, I don't understand why the two components of the satellite have similar sizes. This is going to be fun for the scientific community to figure out."

Why study asteroids in our solar system

The NASA mission was given the name Lucy after the famous early human fossil discovered in 1974. Just as Lucy the australopithecus helped us understand the early stages of human evolution, the Lucy spacecraft can help us understand the early stages of the solar system.

According to current astronomical models, the planets of the solar system formed from a large disk of undifferentiated material which orbited the sun. As dust and gas clumped together in the disk, they formed knots of denser material. These knots then attracted more material through gravity, growing over time to become the planets of our solar system.

It's difficult to study planetary origins in detail. Even on Earth, the constant tectonic shifting of the crust effectively recycles rock, drawing it back into the molten mantle and redistributing it in new places. So although we know the Earth is around 4.5 billion years old, it is rare to find rocks that old. Asteroids are different. As leftover pieces from planetary formation, asteroids don't have tectonics, atmosphere, weather, or any other forces that degrade geological evidence. Effectively, asteroids are samples left over from the time the planets formed. By studying them, scientists hope to better understand the early history of the solar system.

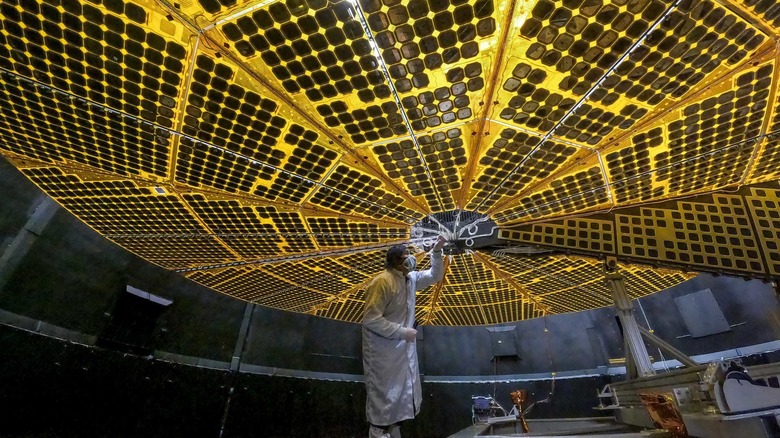

Troubles with Lucy's solar array

This mission hasn't been trouble-free. Lucy's two solar arrays have been a particular struggle. Spread out on each side of the spacecraft, these large round structures of solar cells collect energy from the sun to power Lucy's systems. To tuck Lucy into the nosecone of a rocket for launch, the arrays had to fold up. The plan was for each array to unfurl like a fan into a full 360-degree spread, then latch into place.

One array did that perfectly. The other didn't latch following launch. That posed two problems: The solar array needed to cover maximum area to get Lucy sufficient power, and it had to latch into place to be structurally sound. If it wasn't locked, it could be damaged whenever Lucy fired its thrusters.

The team tried multiple tactics to deploy and latch the stuck array, such as using the backup motor to tug the array's opening lanyard. In the end, while the array didn't catch, it did end up covering between 353 degrees and 357 degrees. That allowed the mission to continue. Thus far, the spacecraft is in good health and generating the power it needs.