There are no photographs of my father holding me as a baby. Or, if there are, I’ve never seen them. He’s never brought them out and gotten misty remembering the day his first child, his parents’ first grandchild, was born. He was not in the delivery room that morning; it would be many hours before he met his son.

This isn’t surprising—in those days, fathers took no part in childbirth. Our modern idea of the supportive husband crouching at his laboring wife’s bedside, holding her hand as she screams and sweats and shits herself, would have baffled and horrified a man of his generation—and in any case, my mother was unconscious through the whole thing, as was also the norm.

It was early September, the damp heat of late New Jersey summer. Six weeks earlier, a man had actually touched the moon. They’d gone to the hospital late at night, and once they wheeled my mother away, he didn’t see her again for eight or ten hours. What did he do during those hours? Did he pace the waiting room, take a walk, call his parents, watch TV? He can’t remember, he tells me. Was he anxious? Scared? Not particularly. So I’ve decided he felt happiness. Yes, I’m sure of this. He must have felt excitement, pride, anticipation—he’s done it, after all. He’s fulfilled the path laid out for him by his father, by his father’s father: college, law school, a good career, a wife, a child. Within a few years, there will be a house in the suburbs. He is a success. He is not concerned about the work ahead—the sleepless nights, the diapers, the laundry, the laundry, tasks that will have no impact on his life, as the feeding and changing and bathing and strolling will fall to my mother and the night nurse, my father being expected only to keep bringing home the paycheck. One imagines the confusion a man of his generation would have felt if offered paternity leave: For what?

Sometime the next morning, a nurse leads him to my mother’s room. What time? No idea. And there she sits, his wife, drowsy and half-upright, a baby crooked in her arm and sucking from a bottle: tiny and pink, legs kicking, impossibly real, his. What goes through his mind? What does my father feel? He can’t tell me. But is it possible not to feel an overwhelming desire to hold it, him, me? Is it possible not to want—no, need—to press that baby to your bare chest, curl your body around him, sobbing with the beauty and pride and responsibility of it all, to cup his small head in the palm of your hand, your hand that seems suddenly huge and safe and strong, to rock that baby and sing soft nonsense syllables until its kicking calms, its little squalling sounds quiet, its bright, wide eyes flutter and fall beautifully to sleep? How could a man of any generation, holding his newborn child, not feel these things?

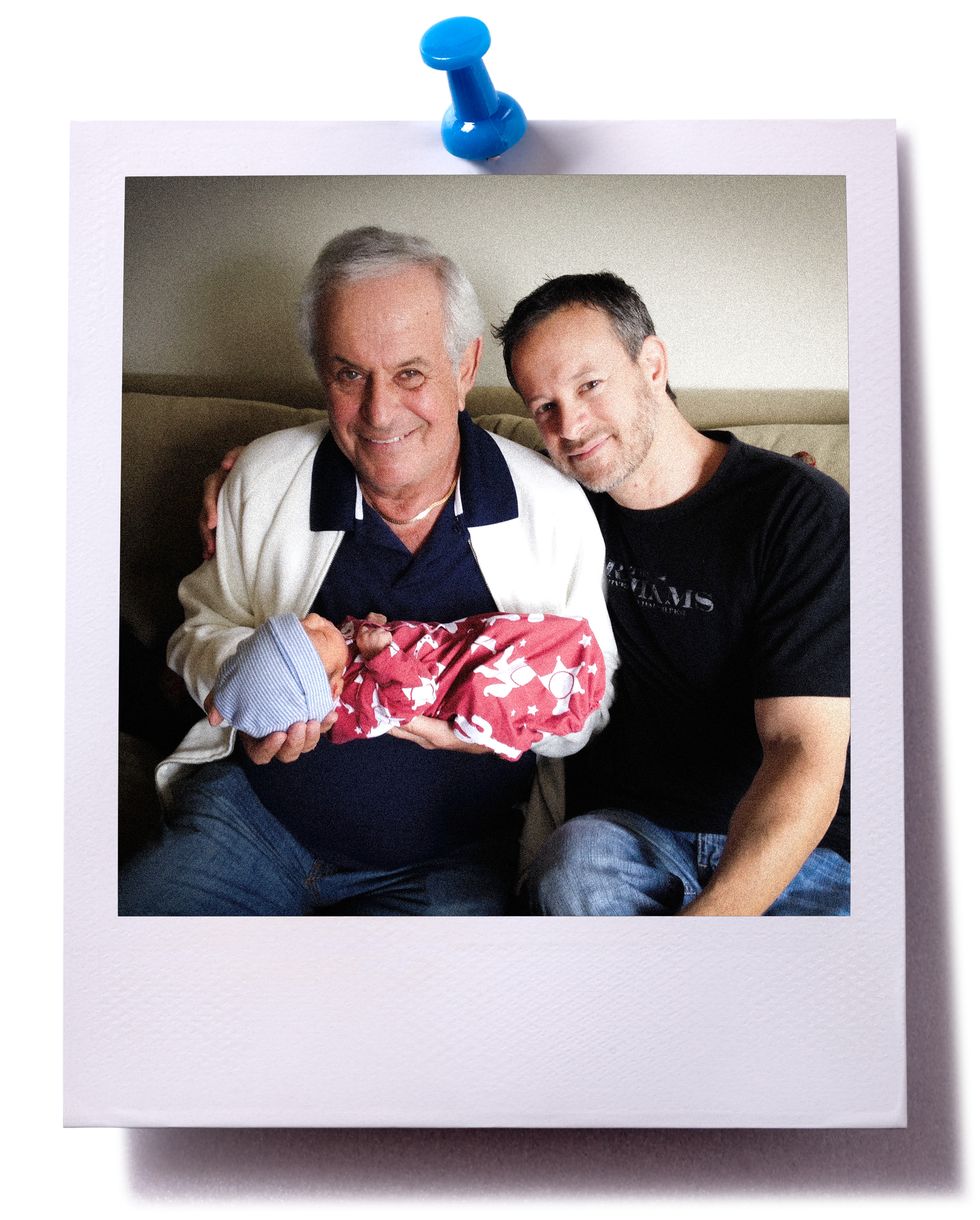

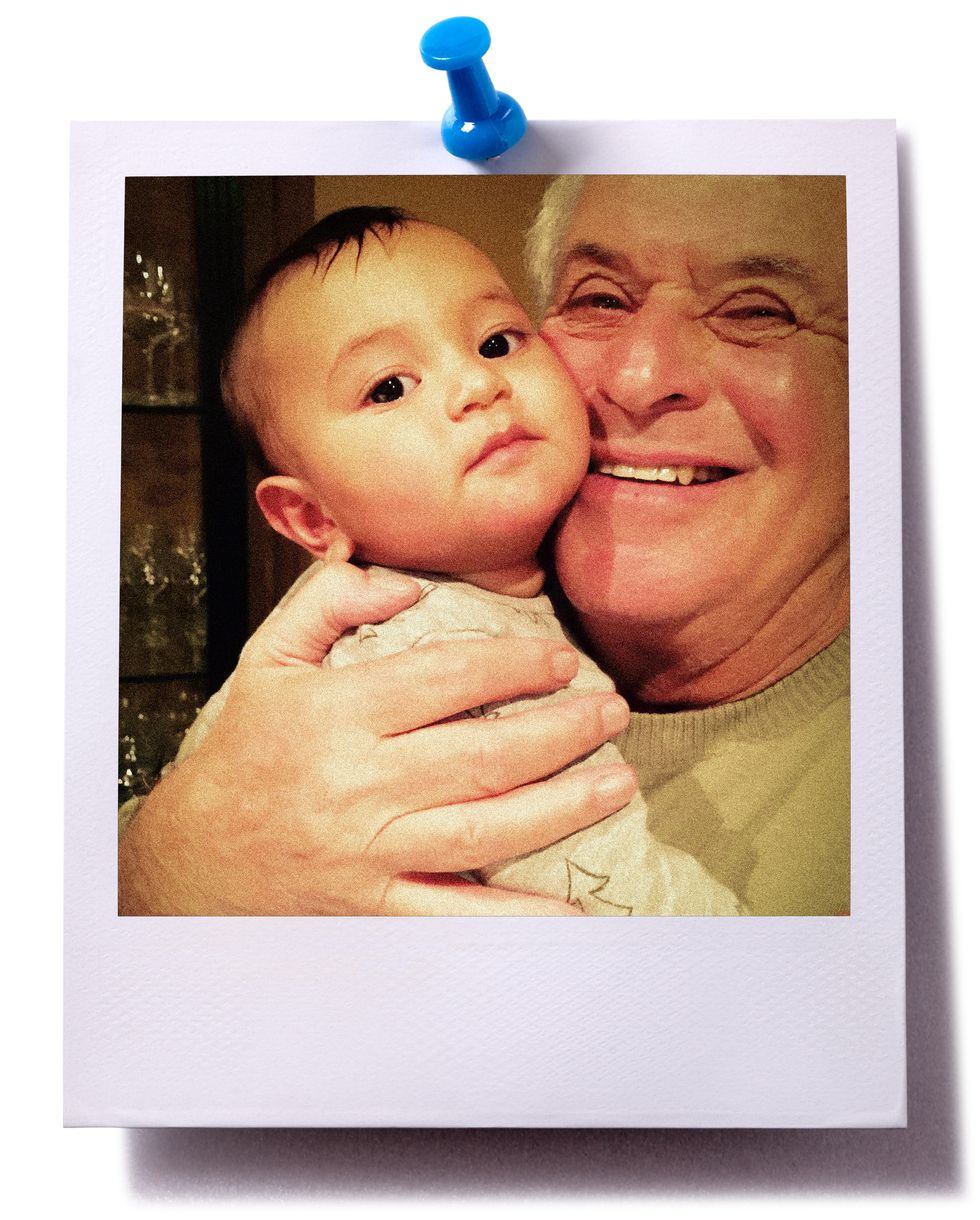

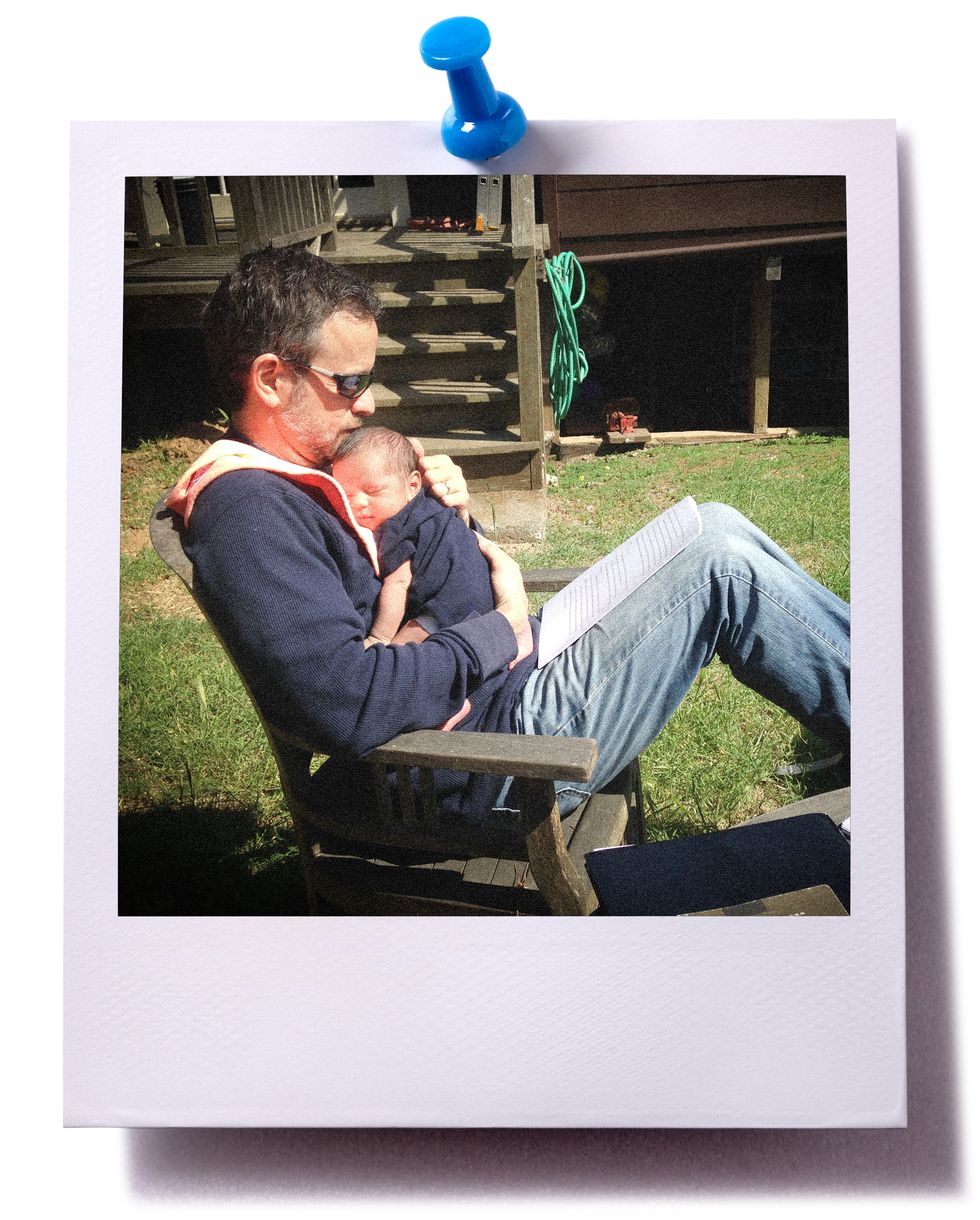

Forty-five years later, he would hold my son—his grandson, his only grandchild—for the first time. He sat on my couch in San Francisco, three days after my son was born, and I spread a blanket on his lap and brought the baby to him. The look on his face was one of terrified incompetence, but I insisted he hold the baby, showed him where to put his hands, assured him he need do nothing but hold him. I have a photo of this moment, my father cradling my newborn son, and I can’t look at it without a hot ache coming into my throat. He’s seventy-six years old, his brow furrowed in concentration, his lips slightly parted, his hands gentle and strong. So why is there a glimmer of sadness in his eyes?

On his fifth day of life, we took my son for his first stroll. My wife, my parents, and I set out for a nearby park, the baby nestled comfortably in his blankets. It was a Friday morning in April; the streets of our San Francisco neighborhood were mostly empty. I beamed with pride as I pushed the stroller, the world warm and glowing all around us: I was a father.

A block or so from our apartment, I spied a figure coming toward us, still a hundred feet away. In my memory he was moving erratically, perhaps drunk, perhaps one of the men who slept outside the nearby BART station—but in reality, he may have been just an unfamiliar, nondescript male whose path would soon cross ours. What I felt, in that thoughtless instant, was like nothing I’d ever felt before: I stood taller, my chest puffed out, my grip tightened on the stroller’s handle. My breathing slowed and my eyesight sharpened. I’m not a large man, but in that moment I was enormous, monstrously powerful. I’m not violent by nature, but this was pure instinct, pure atavism—I was ready to put my body between my child and danger, to destroy that danger with my bare hands.

A moment later, the danger passed: the man walked by without incident, probably baffled by the forbidding stare I kept locked on him the whole time. And then it was just another beautiful morning, the breeze gentle, the sounds of birds and cars returning. My wife nudged me and asked what was wrong. But nothing was wrong. For a few seconds I’d been out of my mind, out of my self. I’d felt as an animal feels when its offspring is threatened: no words, no scruples, only violence. I would have torn that man—any man—to pieces to defend my child. Now I felt slightly ridiculous. But nothing was wrong: I was a father.

For a year or so after my son was born, I found myself feeling angry at my father. Driving home from work, or pushing the baby’s stroller in the park, I would think of my father and feel my jaw tighten with resentment. It didn’t take long for me to figure out where it came from: the overwhelming love and protectiveness I felt toward my infant son, the pain I felt when I had to leave him, was not something I’d ever heard my father describe. It was not something I could imagine him feeling. Why didn’t he feel it? Why didn’t he ever say to my mother, “Let me hold him, I need to hold him”? How could he have left the house every morning and put me out of mind for eight, ten, twelve hours until he returned, breath warm and smoky with Scotch, quickly ruffled my hair or maybe kissed my forehead as I slept before sitting down to eat the dinner my mother had cooked for him? And how might I be different had I felt from my father, every day of my childhood, the visceral and attentive love I am helplessly driven to lavish on my own son? Who might I be?

Tempting: to blame it on the times, on the generations. Tempting to say things have changed. But have they?

In the fall of 2020, with the presidential election less than a month away, Donald Trump and his minions opened the floodgates of nastiness against Joe Biden and his hapless son, Hunter. In the first debate, Trump unloaded on Hunter—his business failures, his history of drug problems, his discharge from the military—only to be parried gracefully by Biden, who not only defended Hunter, but told the world how proud he was of his son, that he loved his troubled son. Trump’s cruelty, for once, didn’t work—much to the astonishment and fury of his supporters, who’d cheered wildly as he ran his sword through a defenseless victim, as he made the victim’s father watch. On my couch, with my now-five-year-old asleep downstairs, I actually flinched at Trump’s attack, at the gratuitous viciousness of trying to hurt a man’s child.

But viciousness—especially gendered viciousness—is part of the MAGA brand. Trump’s followers are disgusted by the warmth with which Biden talks about this wayward son, and by the quiet dignity with which he comports himself—a dignity that stands in glaring contrast to Trump’s flamboyant domination displays, to the sneering and manic cruelty of his own sons, Don Jr. and Eric, about whom Trump has never said a loving word in public (or, one suspects, in private). A few weeks later, John Cardillo, an ex-cop and prominent right-wing troll, tweets a photograph of Joe and Hunter. The adult son stares straight at the camera while the aging father, in profile, cups the back of his head and kisses his cheek. It’s a deeply moving image, its black-and-white rawness revealing the indomitability of the father’s love, its enduring power over him. The text of Cardillo’s tweet seethes revulsion: Does this look like an appropriate father/son interaction to you?

If there’s one image that encapsulates the bleakness of American masculinity, it is that tweet, with its summary rejection of fatherly love. Reading it felt like being kicked in the stomach—how many times had I kissed my son like that? Even now, in the 21st century, American men are not permitted such love. We are allowed neither to feel it for our sons, nor to receive it from our fathers. To experience such love—to be made helpless by it, as Biden so clearly is—is to forfeit all claims to manhood, and thus to respect, influence, power. To have been its recipient is to be crippled from birth, deprived of the proper training in imperviousness and cruelty. In America, every real man is an island. Love, true and enduring and unconditional, is something we must not experience. It is inappropriate. This is the message of Trump’s ongoing attacks against Hunter—the taunting, the name-calling, the suggestion that Hunter should be sentenced to death, a relentless campaign to destroy the father by destroying his only surviving son: Joe Biden is not man enough to be president, because Joe Biden is capable of love.

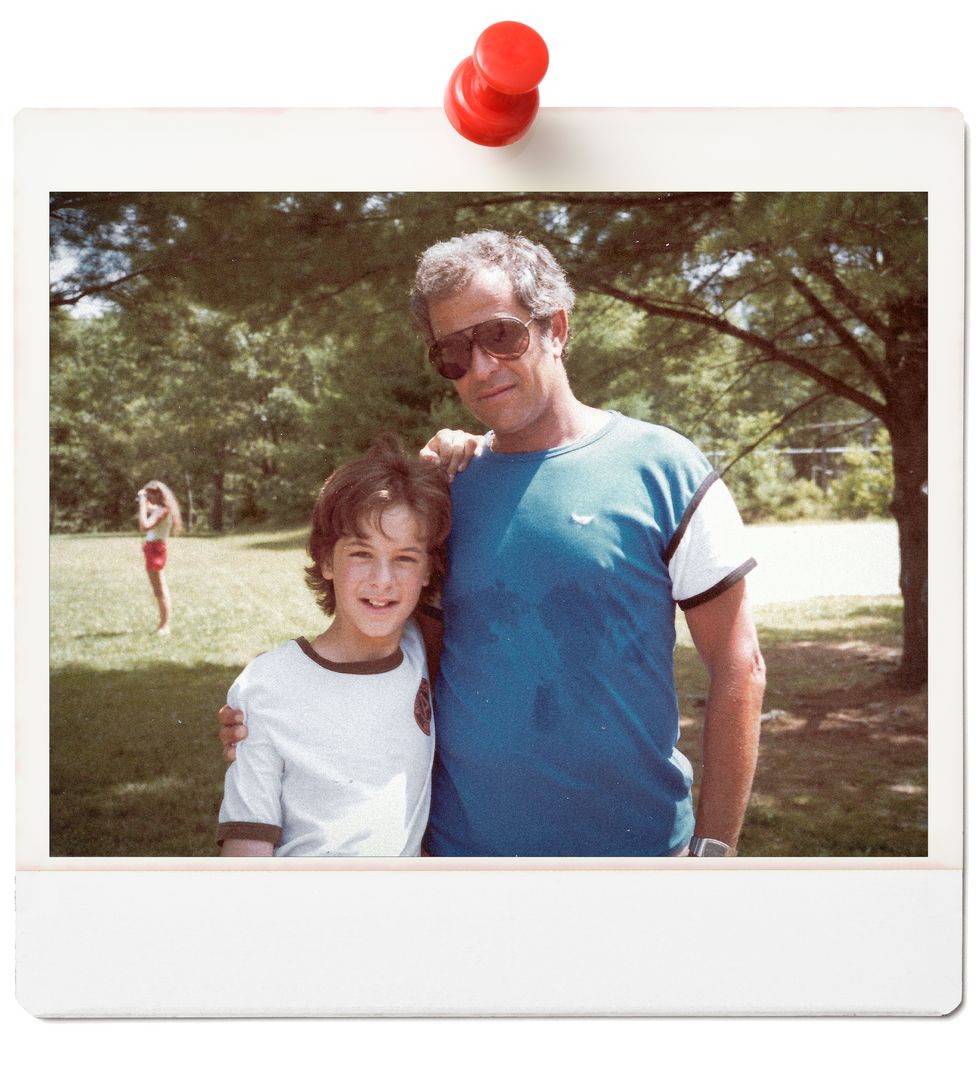

My father is not cruel. He’s not arrogant or domineering. He can be gruff, but he isn’t cold or withholding. He is, essentially, a kind man. As he’s aged, he’s become more vulnerable, more open in his affection—but that’s not how I remember him when I think of my childhood. In fact, I don’t remember much—small things: the smell of his aftershave, the thin vine of cigarette smoke climbing from the ashtray on his nightstand, his conversational baritone resounding through the walls, the rumble of the garage door late at night and the drowsy excitement I felt lying in bed: Daddy’s home.

If I woke early enough, I could be the one to bring him his coffee, an honor he greeted with a half-sleeping grunt. Then, he was gone—to work or, on weekends, to the golf course. He didn’t read to me or help me with my homework; we didn’t ride bikes or build model airplanes in the basement. I don’t remember him attending many of my Little League games—I doubt we played catch in the backyard more than half a dozen times. There were no camping trips, no heart-to-heart talks. It was my mother who explained about the birds and the bees during a family dinner at the Iron Horse Tavern, while my father tucked into a ribeye steak. I don’t remember him teaching me how to do anything except make his nightly Rob Roy.

But I loved my father. Though I didn’t know him well, I admired him. I admired the way he wore a suit, and the poise with which he held a cocktail in one hand and a cigarette in the other. I savored the sound of his electric shaver, the voice of Johnny Mathis on the stereo while he and my mother dressed for a night out. I envied his quick-wittedness, the easy humor with which he circulated at a party. He was, in my estimation, debonair, successful, a well-liked man about town. His ease in the world amazed me. As I grew toward manhood, it shamed me. How would I ever live up to it?

Blame it on the times. In those days, fathers weren’t expected to do much of the parenting (a gerund that was not yet widely used, though “mothering” certainly was), only to take up the briefcase each morning, go forth, and succeed. It’s much different nowadays. Isn’t it?

My wife hears no end of complaints from female friends about husbands who don’t contribute equally to the care of their children, who prioritize their careers, their friendships, their workouts, their happy hours, sometimes refusing to do their share but more often just being oblivious to it. Taking the kids to the doctor, filling out their school paperwork, buying their clothes, straightening tornado-struck bedrooms—such tasks inevitably fall to the mothers, while the fathers watch Monday Night Football and grill steaks and catch up on Facebook. During the pandemic, stories abounded about the unequal division of labor in locked-down families, about men who for years had insisted they would absolutely love to do more with the kids but simply didn’t have the time. Now, the stories went, they had nothing but time, and—surprise, surprise!—they still expected their wives to do the lion’s share.

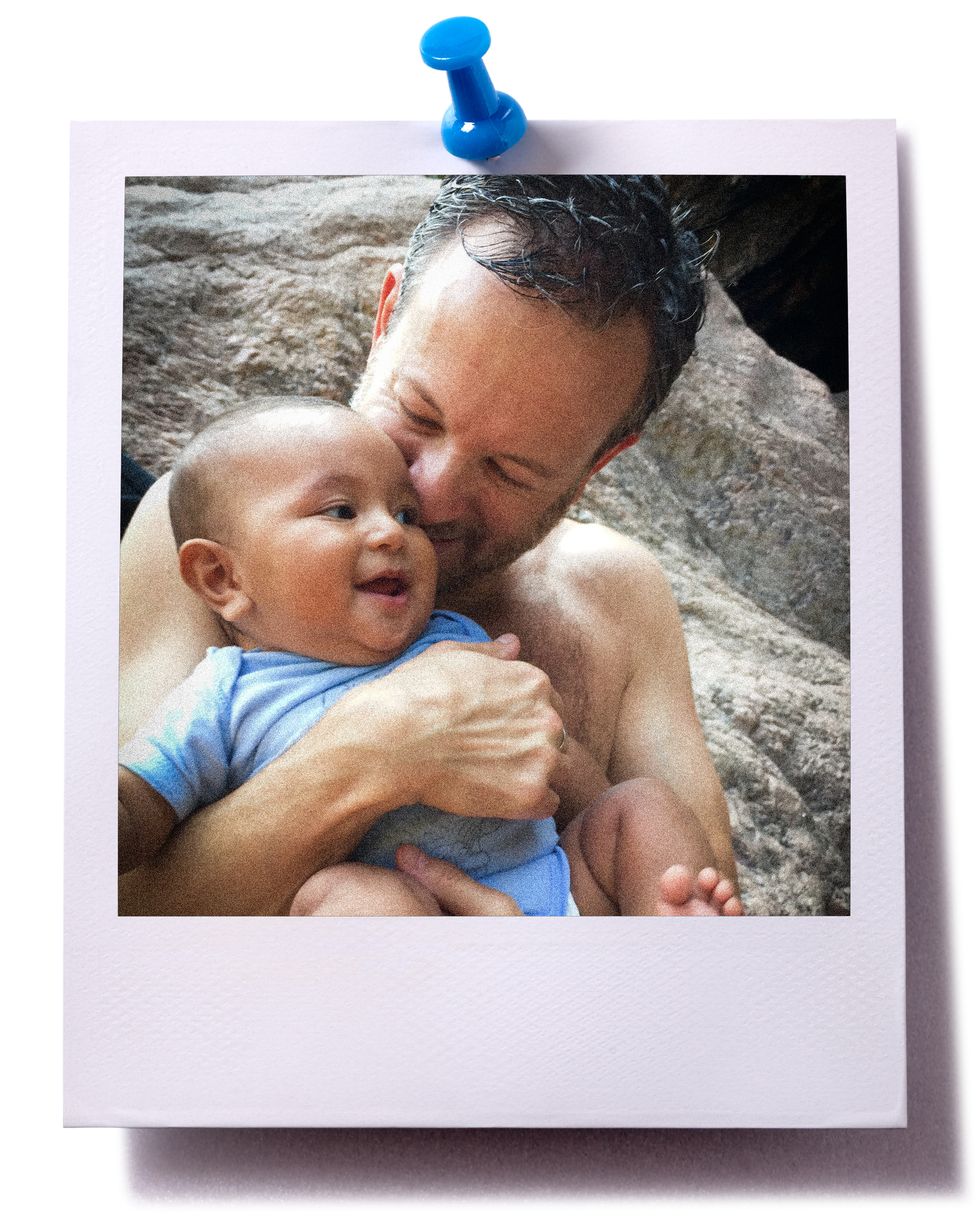

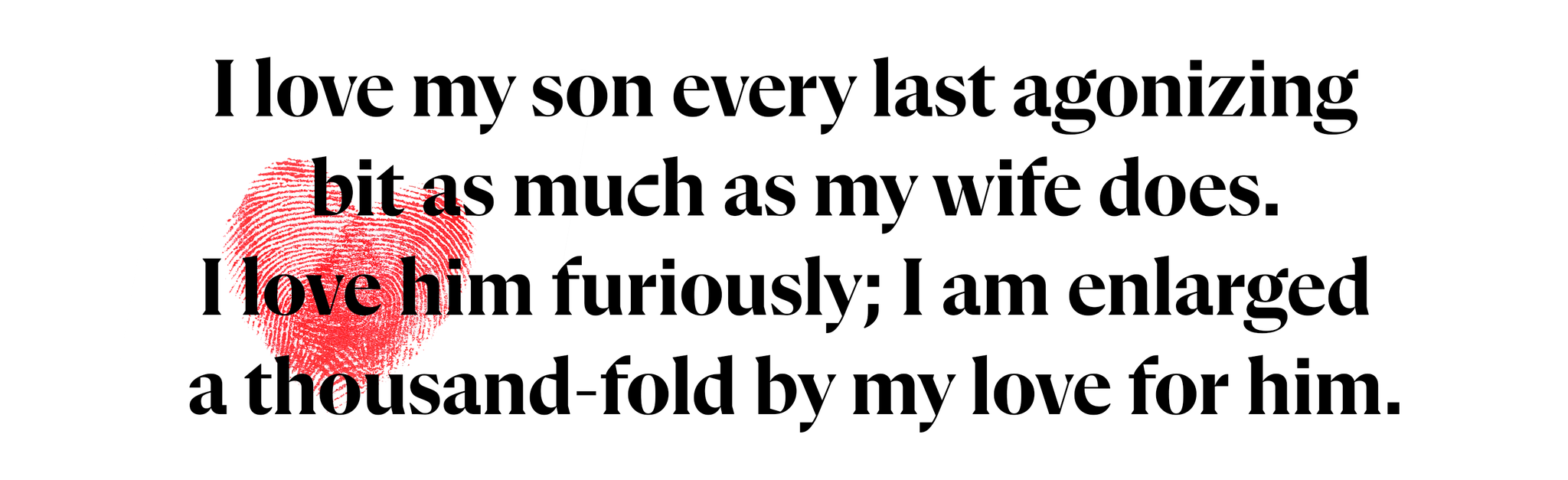

Such reports astonish me. How can it be that, in the 21st century, so many men shirk their share of parenting? Why is it permitted? Let’s please not talk about biology or maternal instincts. Don’t tell me a mother feels a deeper bond, having carried the child in her body. I love my son every last agonizing bit as much as my wife does. I love him furiously; I am enlarged a thousand-fold by my love for him. In my house, we come pretty close to 50/50 parenting. It would no sooner occur to me to leave the majority of the work to my wife than to drive on the left side of the road or cheat on my taxes. I don’t see anything especially admirable about this. Yet I have to admit, for all my self-celebrated egalitarianism: sometimes I’m tempted to shirk, to let my wife pick up the slack. I know I could get away with it—that my wife either wouldn’t notice or would roll her eyes. For all I know, she would say that I do shirk from time to time, that I’m the oblivious one, that this 50/50 thing I’m so proud of is a crock. Why should I—why should anyone—get away with such behavior? I’ve never seen a film, or a television show, or an advertisement, in which a father is the primary parent and the mother the breadwinner. Or, rather, I’ve never seen such a film that wasn’t supposed to be a comedy. Who’s writing and producing this stuff?

Sure, parenting is difficult and messy. Caring for an infant, caring for a child of any age, is hard, harrowing, frustrating work—does anyone really look forward to sleeplessness and vomit and dirty diapers and endless shrieking? Our son didn’t sleep through the night until he was twenty months old, waking in 90-minute cycles and howling inconsolably for up to an hour —twenty months during which my wife and I often felt murderous toward each other and something less than adoring toward our bundle of joy. If someone had come to me during this miserable year-and-a-half-long fugue and offered to relieve me of this burden, to let me trade it in for a few extra, well-rested hours at work, I might have wept in gratitude. But no one offered me this deal.

Anyway, I like to think I wouldn’t have taken it. I like to think the overpowering love and paternal instinct that surged up in me the night my son was born would have made that deal seem ridiculous, offensive. I like to think that nothing could have kept me from holding my son every day of his life, for hours on end—rocking him, singing to him, waking with him, cleaning his vomit off my shirt, his shit off my wrists, weeping in exhaustion at 3:00 AM, nodding off next to his crib at noon, washing and folding infinite onesies. I like to think—no, I’m certain, that I would not have given these things up for anything in the world, and I’ve spent much of my life wondering, consciously or not, how my father could have. How, Dad?

It doesn’t help that he thinks it’s funny. It doesn’t help that whenever the subject of my infancy or my sister’s infancy comes up, whether he has a large audience or it’s just our family, he puts on his most rakish grin and says, “I think I changed your diaper… once,” then sits back to enjoy his punchline.

Here’s his favorite story—the one he saves for special occasions. I was fourteen months old, and it was the first time my mother left me alone with him. It was a Saturday afternoon, time for college football. But not just any college football: the annual Michigan-Ohio State game, and my father, an alumnus of both, would not miss it come hell or high water. So we’re home in our Fort Lee apartment on a pleasant afternoon, my father engrossed in the television, a beer on the coffee table. Maybe I’m playing with blocks on the floor, or maybe I’m on his lap—but at some point he notices that I’m not moving much, not making my usual squeals and babbles. He picks me up and what shoots through his mind is: HOT.

“Andy? What’s the matter?” He bounces me, shakes me gently. “Andy?” The baby’s head is lolling, his eyes glassy. Where is my mother? Where is she? Clothes shopping, perhaps, or having lunch with a friend. It’s Saturday, there’s a great game on TV, but there’s something wrong, something definitely very wrong with the baby—and inexplicably, it is my father who has to deal with it.

At the hospital, he's told I have a dangerously high fever—a convulsion, they’re calling it, probably brought on by a virus—but they’re giving me antibiotics and I should be fine. He did the right thing, got me there in time. Meanwhile, my mother is coming home to an empty apartment, the stroller still folded next to the door. I imagine her dumbstruck, dizzy with dread: nothing short of the Rapture could explain her husband and son’s absence. Eventually a neighbor tells her what’s happened. Eventually she finds my father at the hospital, talks to the doctors, sees her baby who is now sleeping comfortably. It’s a happy ending. But what I want to know is, what did my father look like when she found him? What did she see in his eyes? Because in the fifty years he’s been telling that story, he’s never once talked about fear. He’s never teared up. His voice has never caught, remembering the time he feared his baby might die in his arms.

Instead, he punches me on the shoulder and says, “You ruined the Michigan game, you little bastard!”

Four decades later, my son was admitted to a hospital in Colorado with a suspected case of meningitis. He was five months old, and we’d been living in Fort Collins for six weeks—not long enough to find a pediatrician or to even begin to unpack the stacks of moving boxes. We’d woken that morning and noticed that his fontanelle, the soft spot at the crown of his head, was bulging, warm to the touch; if you looked closely, you could see his pulse. At urgent care, they’d wasted no time in sending us up the road to the hospital. They’d need a blood test and a spinal tap to rule out meningitis, they told us. What they didn’t tell us was that the results wouldn’t come back for 48 hours, and that he’d need to be on IV antibiotics that whole time, just in case.

I don’t remember the drive to the hospital. I don’t remember filling out paperwork or finding our way through the labyrinth of hallways to where the doctors with the needles were waiting. It took almost two hours for them to draw my son’s blood and spinal fluid, two hours during which he screamed in uncomprehending agony at the dozens of unsuccessful needle sticks and bawled with hunger because they would not allow us to feed him until they’d gotten what they needed. I remember crouching in the corner of the exam room, tears running down my face. I remember literally pulling my hair. I remember bellowing in fury at the increasingly frustrated doctors, calling them the “Keystone Kops.” I remember the ending of Ernest Hemingway’s story “Indian Camp,” in which the husband of a Native American woman who undergoes an emergency C-section without anesthesia slits his own throat because he can’t endure the sound of her suffering; there were no scalpels at hand, but I remember whispering, “I can’t take this,” over and over. I remember—my wife and I remember—fear. Bottomless, uncontrollable fear. This baby, this helpless creature, was our life and our charge, and we were failing him. We might lose him.

He did not have meningitis. After two nights in the hospital, my wife and I trading off shifts in a narrow cot, sitting by his bedside and singing to him, holding his hands so he wouldn’t pull out the IV, the tests came back negative and we went home. It’s a happy ending. But I’ve never told him the story. In eight years, it hasn’t come up. What will I say when it does? How can I convey the terror of those hours, the insanity that took me as I watched strangers stabbing needles at his flesh, as I listened to cries I was powerless to soothe?

I can understand the urge to deflect it. The need to make light, to whistle past the graveyard. “You made me miss my yoga class!” I might tell him. Or, “Who knew a tiny baby could make so much noise?” Because telling him the truth—that I thought he might die, that my life would have ended, that nothing after that would have meant anything next to my failure to protect him—would expose the most vulnerable and frightened part of me, the part that fears I don’t deserve him, that I’m not good enough to be his father. And that’s something I don’t want him, or anyone, to see.

So maybe I’ll hide it. Maybe I’ll shrug it off, tell a joke, punch him in the arm like my father does to me.

No, I won’t.

I’m well acquainted with bravado. As an American man, I understand the need, the requirement, to project strength at all times, an air of imperviousness. No Stranger to Danger! For American men, the imperative to demonstrate masculinity by abjuring emotions like fear, grief, empathy, even joy, is ever-present, so fundamental we don’t see it anymore.

It’s a trap, set by our culture’s boundless misogyny, sprung in bar rooms and boardrooms, schoolyards and social media, and yes, presidential debates. “[M]any men are afraid to change,” bell hooks wrote. “Masses of men have not even begun to look at the ways that patriarchy keeps them from knowing themselves, from being in touch with their feelings, from loving.”

So I’m not interested in bravado, mine or anyone else’s. What interests me is what bravado costs. What it hides. After a lifetime of such performances, I want to know if those feelings still exist, if they still happen, swimming through the psychic darkness like koi in a pond. Tell me, Dad, that you were terrified. Tell me that you wanted to die. Or tell me it was the fourth quarter, the fourth down, your beloved team in field-goal range with a last, desperate chance to come from behind.

This tension between resentment and love, between strength and tenderness, how it can be psychically crippling for fathers and sons, is one of the most wrenching themes of Justin Torres’s novel-in-stories, We the Animals. In its last movement, the narrator, the youngest of three boys being raised by young, volatile parents, is coming to understand that he’s gay—a discovery that terrifies him, setting him forever apart from his domineering Puerto Rican father and from the older brothers who’ve hewn closer to their father’s example. Readers have seen ample evidence of the father’s brutality—he beats his sons when they misbehave, and his sexual aggression toward their mother often crosses the line into rape—but also his capacity for love, even sweetness. He’s magnetic, fun-loving, a great dancer; he cheers his sons’ achievements with outsized enthusiasm. How difficult to please such a man-child, to stay on his good side.

As the adolescent narrator’s difference grows clear, we brace for him to be discovered, to find out which of the father’s tendencies, love or cruelty, will prevail. On the night when he finally acts on his desire, in an ambiguous encounter at a bus station (Torres called this chapter “The Night I Am Made”), the narrator comes home to discover that his family—father, mother, brothers—has read his diary, full of graphic homoerotic fantasies. Standing before this tribunal, the narrator reacts with his own savagery, an explosion of terrified violence that only the father’s greater strength can bring under control.

What follows are five pages of astonishing emotional complexity, during which the father forces the narrator into the bathtub, unscrews a lightbulb like some C.I.A. torturer setting the scene, and then… bathes his son. He washes his son’s naked body, cleans his self-inflicted wounds, clips his nails, murmuring words of comfort, expressing with his hands and his care all the love he has too often withheld. “Mijo,” he says. “My son.” The father is in pain, too—we may disapprove of that pain, born as it is of homophobia, but we can’t deny it or look away from it. “We’re getting him fixed up,” the father tells the mother: the boy is broken, and the father, trapped in toxic manhood, feels it is his fault.

There is such agonizing failure in this scene; though it’s only five pages long, it feels like it goes on forever, this unbearable confluence of love, violence, atonement, the Biblical echoes of baptism and pietà. A reader hopes it will go on forever, knowing as we already do that when it’s over, the narrator will be expelled from the family and committed to a mental hospital. We’ll never see reunion or reconciliation—only an implicit assurance that he’ll survive, however damaged, that this is indeed the night that “made” him, turned him into the man who can look back on this story with forgiveness and love. At some level, the narrator understands, his father has also been condemned: he, too, will be in prison. He always has been.

I felt angry at my father for a long time. When I talked to him on the phone, I found myself describing at great length all the active parenting I was doing—the long nights, the messes, the trips to the pediatrician. On some level, I was rubbing his nose in it, showing him I was the better man. Why did I think he would care? The man I’ve described, the one who had no interest in doing those things, could feel only perplexity at such stories, perhaps pity—certainly not envy or shame.

But I persisted. When he visited, I insisted he hold the baby, and I relished his discomfort. I baited him into telling the old stories: how he never changed a diaper, how I ruined the Michigan game. I was compelled to get back at him somehow, to draw blood from this stone. Years later, looking through photos of my son’s first few months, I found one taken at a restaurant on Orcas Island, where my wife and I brought my parents for a long weekend when my son was eleven weeks old. In the photo, my father holds the baby with both arms, a secure, protective embrace, his lips close to the top of my son’s head. The smile on my father’s face is so bright with delight I can hardly recognize him. The next morning, he called our hotel room while we were at breakfast. When no one picked up, he succumbed to a fear that something terrible had happened—the baby was sick, and we’d rushed to the mainland to find a hospital. When he finally found us in the hotel lobby, he was frantic, wild-eyed with relief. This was the self-centered father of my memories? This was the company man impervious to love?

Harry Chapin had it right. The singer-songwriter, who died in a motorcycle accident in 1981, is remembered mostly for one song: “Cat’s in the Cradle,” the lament of a father who realizes only in old age, only when it’s too late, that he failed to love his son properly, failed to give him the attention and approval that a child craves from a father. (‘Can you teach me to throw?’ / I said, ‘Not today, I’ve got a lot to do.’ / He said, ‘That’s ok.’). Worse, he’s taught his son all too well the priorities which underwrote that failure—work, success, money—such that his son grows up similarly incapable of showing love. The last line of the final verse—My boy was just like me—might be the most painful lyric ever written about fatherhood.

But the whole song is painful. For me, listening to it is a kind of sweet torture. Though it was a hit almost fifty years ago, I remember every word. I can’t sing along without choking up—the kind of sudden, uncontrollable sob that you can’t sing through. If it comes on the radio when anyone else is around, I have to turn it off. If it comes into my head unbidden, I have to sing it through: every verse, every chorus, knowing the whole time what waterworks await.

I couldn’t have understood, back in the days when it was popular, that I saw my father and myself in it. It was too early for that. My relationship with my father seemed perfectly normal in those days—it was perfectly normal. And that’s the song’s real tragedy: not that fathers and sons don’t want to be close, but that they can’t acknowledge this need. They can’t act on it. They—we—are taught to ignore it, endure it, put it in its proper place. At least in 1974 you could write a song about it, a song that speaks to men’s hidden pain and regret. I don’t know if you could get away with it today. I don’t know if such a song would ever get recorded, could ever become a hit, if an American man would ever expose himself by singing such sentimental crap, let alone buy the record, play it over and over again, alone in his car on the way to his office on a university campus 2,000 miles away from his elderly father, sit sobbing pathetically in the parking lot. Does this look like an appropriate father/son interaction to you?

We had a tradition, for a while, of late-night talks after my mother had gone to sleep. This was long before my marriage and my son, but past the age when one’s parents are central to one’s life, ever-present in one’s sense of the world. I was an adult, home from grad school or visiting from San Francisco; he’d pick me up at Newark Airport and we’d drive up the New Jersey Turnpike, the glare of refineries and power plants giving way to the lush, dark suburbs, then pull into the garage in time for a late dinner with my mother.

“Feel like a nightcap?” he’d ask, and we’d stay up for an hour or two, sipping our drinks and sharing cigarettes, catching up. Rarely did we discuss anything important, but I remember looking forward to these talks all the same, to that quiet intimacy, the two of us held within the gentle halo of a floor lamp.

One night, we got on the subject of fathers. His own father had died five years earlier. He’d never discussed with me how he felt, how much he must have missed him, but something in my father’s demeanor had been subtly changing. His bluff vitality had begun to ebb. He was over sixty now, nearing retirement. We talked about fathers and fatherhood in the abstract, or maybe about other fathers we knew—his friends, my friends—and for some reason I can’t remember now, I said that he’d been a wonderful father, the best I could have asked for, that I felt lucky to have been raised by him. I both did and didn’t believe this. He looked at me and then away from me, tapped his cigarette, and shrugged. With unaccustomed melancholy, he said, “I didn’t really do much.”

That was all. We’ve never had another conversation like it. If asked, I assume my father would say he doesn’t remember it. He’d make a joke, say he must have been drunk. “Remember the time you ruined the Michigan game?” he’d say.

But I saw something that night that surprised me—something I find it hard to put a label on. Was it melancholy? Was it regret? Is it possible my father, looking back, feels he was trapped by expectations, by the rules of manhood—or not so much trapped as formed, limited, incapable of feeling otherwise? Is it possible that, deep down, he did feel otherwise, but was barred from expressing it? Is it possible that he spent the years of my childhood holding back the same torrent of love and pride and terror with which I so embarrassingly soak my own son, that he felt such exhausting restraint was what was required of him, as a father and as a man, and that his only reward after decades of this agonizing self-denial was his son’s resentment for having been so good at it?

It’s a stretch, I know. But there was something in his voice that night, some sadness I’ve never heard again. Maybe it’s the sadness I see in the photo of him holding my son, his grandson, for the first time. At least I think it’s sadness. Please, let it be sadness.

This essay is adapted from the anthology What My Father and I Don't Talk About, available for purchase in May 2025.