One of Kimberly Stevenot’s responsibilities as a kid was to hang out by the side of the road and look for park rangers—or anyone else who looked like they might be trouble.

The Tuolumne Rancheria, where many Northern Sierra Mewuk had lived since they were forced out of their homes, was granite and solid red clay. It was about as bad as a place could be for growing anything. So her family snuck around to the few places where the plants they had gardened for generations still grew. Many of those places were in state and national parks.

Those places were better than nothing, but not great. The parks were overgrown, and the plants needed hand-weeding. Controlling weeds with fire, the way the Mewuk used to, was too risky—so much as picking a berry in a state park without authorization put them in violation of California Code 4306. Later, when they learned more about pesticides, that was another worry.

Sign up today!

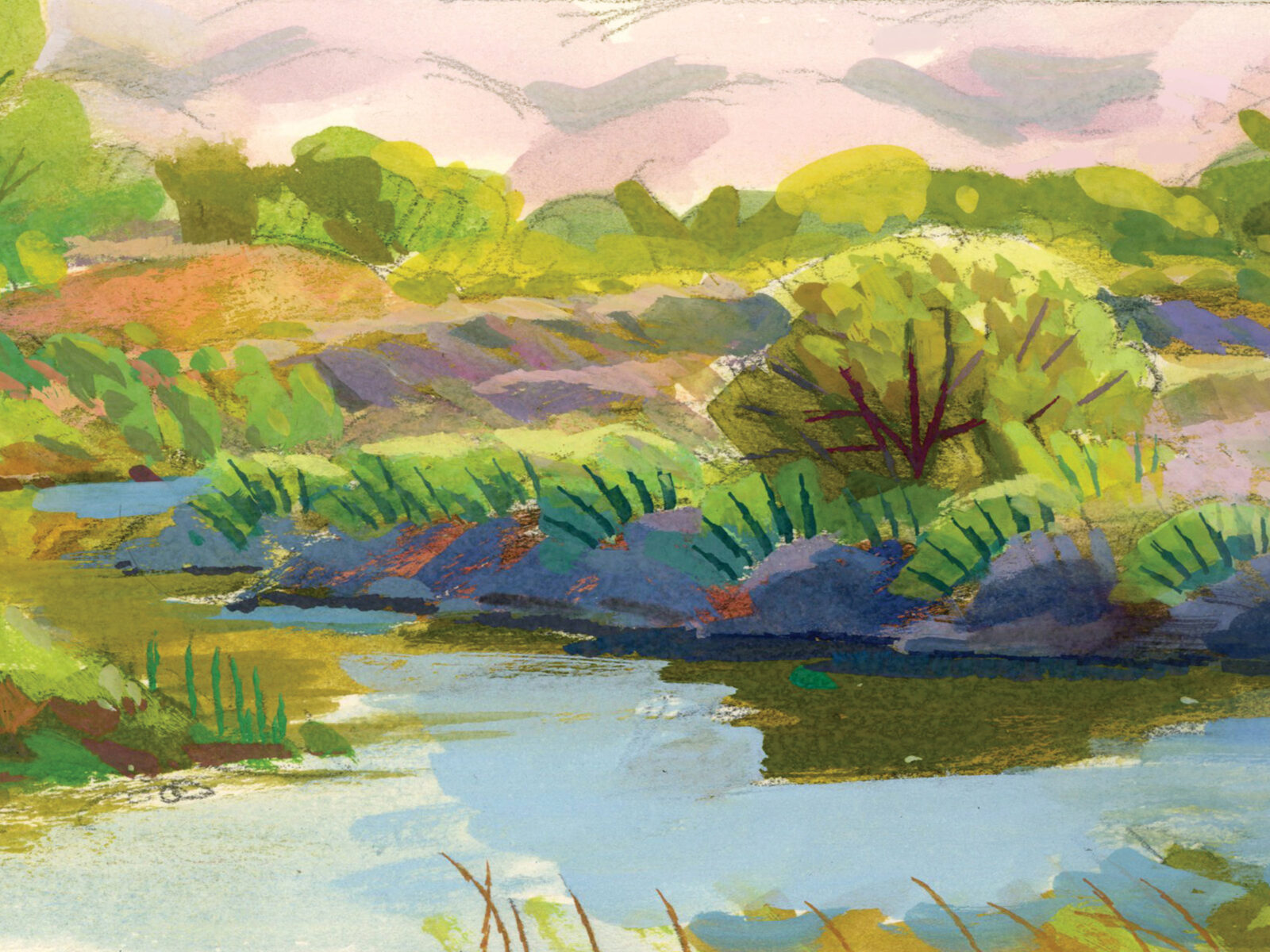

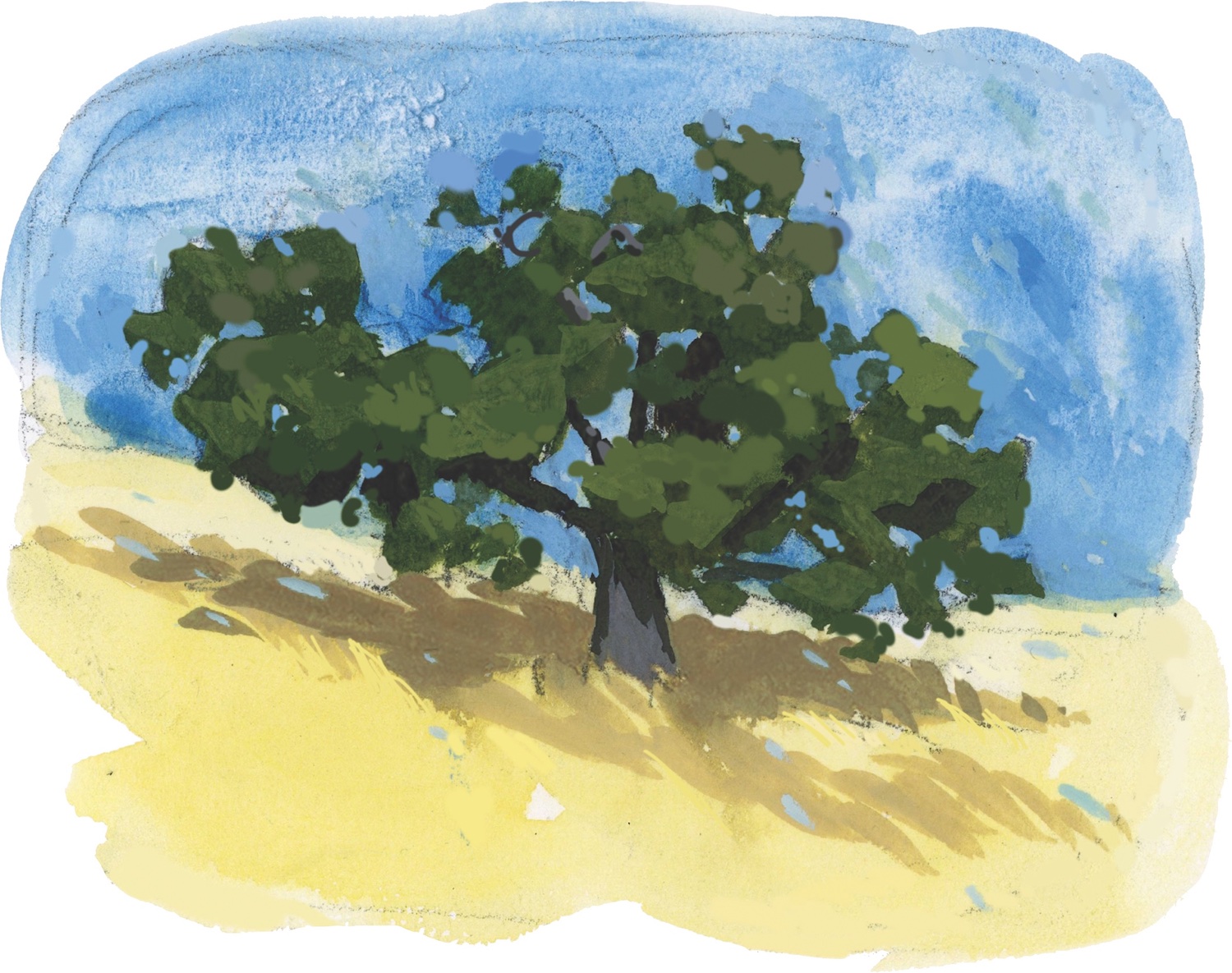

But if they followed a river for long enough, past the long stretches of mining and dredging debris, past the riverbanks kept scrupulously bald for the purposes of agriculture, signs of the old California might emerge—tules, cottonwood, willow, and, in the high loam, valley oaks. A grove of valley oaks creates its own microclimate, a small planet of understory plants and fungi. One of these is the Valley sedge, Carex barbarae, a grass whose rhizomes are one of the most coveted materials for weaving baskets.

Thirty years ago, sometime after her mother died, Kimberly’s husband came back to their home in Modesto, radiant with excitement. He’d spotted something while driving through Caswell Memorial State Park. “I think I found your mom’s sedge beds,” he told her.

Cultivating sedge is a lot of work. People tend to keep their spots secret. If someone starts digging a bed and uncovers suspiciously long, straight rhizomes, they usually know better than to take any—invariably another weaver will figure it out, and give them hell for it later. The sedge Kimberly’s husband had seen had roots all tangled up in its rhizomes. No one was tending it anymore.

Kimberly remembered how her mother and grandmother would follow the Stanislaus River downstream from the foothills of the Sierras, and the abundance of sedge they described finding there. She decided to go see for herself.

Riparian forest is a rare sight in the Central Valley. About one million acres of trees, shrubs, and grasses once flourished, drowned, and flourished again along the valley’s rivers, creeks, and floodplains; now, perhaps 130,000 acres remain. In recent years, though, that number has begun to inch up again. Caswell has about 260 acres. Seven miles south of there is Dos Rios Ranch—2,100 acres, much of it former dairy farm and almond orchard, at the extremely floodable confluence of the Tuolumne and San Joaquin rivers—which is steadily being restored to riparian forest. Later this year it will open as California’s first new state park in 15 years.

“I think of this literally as a park of the future,” says Armando Quintero, California Department of Parks and Recreation director. Today, a California state park has to deliver more than just a historical plaque or a scenic vista. Quintero cites Dos Rios Ranch State Park as an example of what the state’s ambitious 30×30 goals could look like—providing shelter during heat waves for wildlife, storing floodwaters, harboring endangered species.

But it will also be one of the few public parks in an area that has grown rapidly in population with no commensurate growth in open space. Valley residents, many Latino and low-income, have never had the same access to public lands as people who live on the coast. Native inhabitants of the valley have lost so much that the scale of it is difficult to even imagine. Quintero has heard that one of the almond orchards at Dos Rios will stay a few more years—that particular lease isn’t up yet—and he’s delighted about that too. “You don’t usually have a park that has a piece of the agricultural story of the Central Valley,” he says. “We used to say ‘man and nature’ and that always made me pull my hair out. Because man is nature, right? This park is going to be telling a fuller story of California.”

In a larger sense, Dos Rios is also a sign of how much California’s idea of nature is shifting. Dos Rios is becoming a wild space in a landscape that has very little of that. But it also is home to a native-use garden, where Indigenous people can gather culturally important plants without permits, and it will be tended in ways, like traditional burning, that would have been flagrantly illegal a few decades ago. “Our native wildlife, our native butterflies and beetles and bees all lived in that same cultivation space with California people for thousands of years,” says Julie Rentner, an ecologist and the president of River Partners, the nonprofit that bought this land to restore it. “They’re all adapted together.”

Until the 1850s most of California was, basically, a native-use garden. One of the most vivid descriptions of what that looked like, at least in one part of the Central Valley, comes from interviews done a century ago with Thomas Jefferson Mayfield, the child of white settlers who was taken in by local Choinumne Yokuts in the 1850s after his father disappeared to herd cattle. Mayfield describes growing up in a wildly lush landscape where residents lived so well on acorns, mustard greens, tule roots, ground squirrel, deer, and other wild forage that everyone spent hours a day playing agility games on a hard-packed sand court they’d built in the middle of their village.

By 1862, it was all over. Mayfield’s family had been only the first of many waves of squatters who killed or chased away the wild game, cut down the trees, brought in livestock that pooped in the waterways, banned fishing and foraging by anyone who wasn’t themselves, and murdered anyone who objected. The surviving Yokuts either left the area or eked out a living shearing sheep and doing laundry for the same people who had destroyed the system that they depended on.

In the 1920s, at the request of the newly created State Parks Commission, landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. and a team of volunteers began traveling the state, looking for iconic California landscapes to parkify. Land was cheap (because of the Great Depression) and the state was flush with federal money (because of the Great Depression). An opportunity like this would not come again.

Olmsted’s report to the Commission laid out the usual suspects: mountains, redwoods, coastline, desert. But he also made an impassioned case for preserving riparian areas for scenic, recreational, and ecological reasons that, he wrote, “would bring far greater dividends than the separate pursuit of one or more of these ends independently.” Former state parks director Ruth Coleman says that the Yolo and Sutter bypasses, a mix of farmland and open space that’s meant to flood, are the closest thing to what he was hoping to preserve.

But even before Olmsted made his trip, the Central Valley’s forests were nearly gone. A riparian forest is, by definition, next to a river, and the captains of steamboats puttering upriver through the Central Valley had few compunctions about pulling over and logging a bunch of trees to feed into their boiler rooms. In 1850, California, with exactly 19 days of statehood under its belt, got itself included in the federal Swamp Act, which gave it permission to dry out any “swamp and overflowed lands” (which, when wet, were federal property, like rivers) and sell the results. The transformation of the valley’s 15 million acres of grasslands, wetlands, scrublands, and forest turned a lush, mercurial ecosystem into something more squared off and controlled—a landscape that people now floor the accelerator driving through between the Sierras and the coast.

When Kimberly was growing up in San Francisco in the 1960s, her mother told her to never tell anyone she was Mewuk. Tell people you’re Filipino, she said. Otherwise no one will rent to us.

But during the fourth grade, after a lesson about the Spanish missions, and after the teacher said one too many times that all the Indians were dead, Kimberly went home and said that she needed to take some baskets to school and lay some truth on the class. Her mother reluctantly agreed. This was long before the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978, and Mewuk could get harassed and even arrested for gathering.

Kimberly doesn’t remember how her classmates responded. She does remember that a student teacher, who was Native Hawaiian, let Kimberly know she was doing the right thing. “That was kind of the smoke before my fire,” Kimberly says, chuckling.

Today, the Smithsonian calls Kimberly on the regular to consult about Mewuk history and culture. While she was on the board of the California Indian Basketweavers Association, she worked with the national parks system and California state parks to legalize native gathering—no more child lookouts, no more sneaking around. She could go to the same sedge beds that her mother and grandmother had used, but legally this time.

Or at least she could in theory. A few months after the permit was developed, Kimberly drove out to see the county’s park district supervisor and get her permit signed. When she found him, the supervisor informed her that he had never heard of such a permit. Also, he added, Caswell’s sedge was off-limits, because the park was home to a very special and almost extinct creature known as the riparian brush rabbit.

“Excuse me?” said Kimberly. “You are talking to one of two Mewuk traditional basket weavers here. You want to talk extinct?”

For the past century, state parks have run on a boom-and-bust cycle—funded when times are good, hung out to dry when times get tough. In the late 1970s, California started “trimming back everything except prisons,” says Richard Walker, a historian of the conservation movement in the Bay Area. California also has a long-standing habit of trying to pay for crucial environmental priorities with bond measures, adds environmental historian Jon Christensen. That includes parks and conservation, but also clean water (2014’s controversial Prop. 1) and climate adaptation (likely on the ballot in November 2024).

One consequence of that unpredictability is that even though Dos Rios has been floated as a possible state park since at least the late 2000s, it was ultimately a nonprofit—River Partners—that pulled together the money to buy the site, with the hope of one day handing it over to a public lands agency. There were no guarantees. “It can be competitive,” says Rentner. “There’s really beautiful properties on the coast and in the forests that would love to become state parks.”

“Bond after bond after bond would come and go, and the money went to the coast,” says Ruth Coleman. As state parks director in the 2000s, she spearheaded the Central Valley Vision Implementation Plan, which sought to develop more state parks in the valley. “If you looked at a map of the California state park system, you will see a bazillion dots along the coast and a lot of dots in urban areas. You will see very few dots in the Central Valley.”

It took River Partners over five years to pull together $22 million in funding to even start the process, from sources like the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the California Wildlife Conservation Board, the state Department of Water Resources, the California River Parkways Program, the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission, and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. River Partners commissioned site analyses, and planned how to un-level the land, and decided which plants would go in where, in what order. They pulled out the concrete riprap, which had been dumped on the riverbanks to keep the river from spreading out. They put in an order for 2,400 pounds of locally adapted native seed (only to find, when it was time to plant, that the price of that seed had tripled).

Map

The valley that was

California’s Central Valley was transformed dramatically by European settlers in the 19th–20th centuries. Now, so much water has been spoken for that habitat restoration focuses on landscapes that are less dependent on year-round surface water—meaning, fewer lakes and marshlands, and more forest, shrublands, and grasslands.

The pre-1900s map at left, from California State University Chico’s Central Valley Historic Mapping Project, aggregates reports from as early as 1874. Some grasslands had already been

converted into agriculture by then, but the map shows the most likely vegetation pre-European settlement.

Maps by Kate Golden. Data via CSU Chicos Geographic Information Center / North State Planning & Development Collective, with analysis by Kristin Quigley, NSPDC lead biologist interpreter.

Each funding agency governed some different angle—navigable waterways, public spaces, endangered species, flood risks. “We had to go through hydraulic analyses to prove that the trees were not going to impede floodwater conveyance,” says Rentner. “It’s intense.” Getting permits to begin restoring the wet side of the levee took four years longer than the permits for the dry side. River Partners had to navigate at least eight overlapping regulatory processes just to get permission to plant trees next to the river.

Coleman worries 2024 could be a return to the bad old days of parks funding. But she’s heartened by the fact that Dos Rios has to be so many things to so many people. Because it plays such a variety of roles—biodiversity, public health, climate adaptation, groundwater recharge—it can pull funding from a wide array of sources.

Dos Rios is also a trial run for how the Central Valley will adapt to climate change. Its 2,100 acres make it large for a park in the area. “I think Dos Rios is going to have untold ecosystem benefits we haven’t even begun to understand,” says Coleman. Ten percent of the irrigated farmland in the San Joaquin Valley needs to come out of production by 2040, as water becomes scarcer. That land could become mango farms—or, as is happening in Kern County, to the south, it could become Amazon fulfillment centers. Or it could be an early link in a chain of riparian restorations along the rivers of the Central Valley—a massive wildlife corridor for migratory birds and other species, as well as a hedge against future droughts and flooding.

If you are going to become a state park, a lot of species will come to rely on you. There are the riparian brush rabbits, sure, but also the riparian woodrats (also endangered) that make little houses for themselves out of sticks. There are neotropical migratory songbirds, which stop here on circuits that can stretch from the Brazilian Amazon to western Canada. There are young chinook salmon, which like to forage for insects, amphipods, and other crustaceans in the relatively still waters of a floodplain, instead of getting banged up in some fast-moving stream.

And there are—well, there will be—humans. A lot of them—from kids spending their first night camping in the outdoors to birdwatchers, to trail runners, to friends and families looking for an affordable space to gather, to locals trying to get cool in the broil of summer, to school groups for whom this landscape and its history are going to become their lesson plan. People who never even visit the park will benefit from the floodplain’s ability to capture and store groundwater and reduce the risk of flooding downstream. If the city bus that makes it all the way out to Shiloh Elementary School in West Modesto can go another two miles, there will be the people who ride out here on transit, or on bikes. The average Modesto resident makes about $33,000 a year—about two-thirds the California average. Sixteen percent of city residents, and 20 percent of children, live below the federal poverty line.

Julie Rentner grew up on the outskirts of public outdoor space like this—near Mount Diablo, which owes its continued wildness to California’s public lands buying spree in the 1920s. “I grew up with crazy privilege, not because my family’s rich,” says Rentner. “I didn’t go to jail as a teen probably because I had access to open space.” Then Rentner, as people do, grew up and fell in love with a guy who enrolled at UC Merced.

Rentner was not sure how to process 1990s-era Merced. The air was bad. The water was bad. Nobody had access to open space. Then she saw a job posting for an ecologist.

The instructions for getting to the interview were this: Drive to the end of Dairy Road, and look for the pickup truck. “I got in with the field manager, Stephen Sheppard—this really unassuming tomato farmer from Chowchilla,” says Rentner. “He goes, ‘We’re just going to show you one of our projects, and see if this is something that you think you’d like to work on.’ ” Sheppard drove up a levee, and a vista opened up beneath them. “Three thousand acres of beautiful marshland and forest,” says Rentner. “All clearly just restored. I said, ‘What the heck are you guys up to?’ ” Rentner had studied forestry at UC Berkeley. At no point had anyone mentioned to her that there used to be forests in the Central Valley. But here one was—the beginnings of one, anyway.

Kimberly found out about Dos Rios in the fall of 2019, when Rentner met a niece of hers and invited the family to come out and talk about native uses of the plants that were being put in on the land. People involved in the restoration understood the role these plants were playing ecologically, but wanted to know more about their usefulness to the cultures that had tended them in the first place. “We brought all our baskets, everything, out here,” says Austin Stevenot, Kimberly’s son. “I’d never heard of River Partners. I live in Modesto, which is 12 minutes that way. There’s 2,000 acres here being restored. And I’m like, ‘Who are these people? What the hell is going on?’ ”

Rentner talked about making Dos Rios available for native use, without permits. “Philosophically,” she said, “this restoration we’re trying to do is actually just our impression of what a cultivated natural community in California looks like.”

“They explained everything to us,” says Kimberly. “Every time I think about it I get really emotional. It’s weird.”

“The entire time, I’m thinking, I gotta work for these people,” says Austin. “Afterwards, I went up and I talked to Julie. I’m like, ‘Hey, you guys hiring?’ She goes, ‘Funny thing, I was gonna ask if you’re interested in a job.’ ”

The contrast between Dos Rios and its surroundings is striking. On the drive there one hot day in July, the rows of almond trees and corn around the future park stretch unto infinity, but when we turn down a dirt road into the future park, the vista of row crops cuts out like a dropped radio signal. In its place are stubby shrubs and scrawny trees—cottonwood and quail bush, planted to fix nitrogen and prepare the way for harder woods like box elder.

As Austin shows us around, he drifts into recipes the way that a character in a musical might burst into song—like the wild duck he rubbed with salt and pepper, roasted in a wood-fired oven and served with garlic chives and elderberry reduction. On fieldwork days, he noshes on whatever’s around. “Everybody else is like, ‘Man, I’m hungry,’ ” he says cheerfully. “I’m like, ‘I’ve been eating this whole damn time.’”

We pass rows of almond trees, torn out at the roots and stacked neatly in piles. This is a place being farmed in reverse, says Austin, who left a job at one of the state’s largest processors of fresh cherries, onions, walnuts, and bell peppers to field-manage the restoration. First the crops go, then native seeds and seedlings are planted. In a few years, the irrigation infrastructure gets pulled out, and these plants will be on their own.

For the five months before our visit, irrigation has been unnecessary. Every plant around us is bisected by a dark stripe, like a bathtub ring—an artifact of when much of Dos Rios was three feet underwater, and Stevenot was getting around by boat. The wet weather was an opportunity to see how the restoration will function as the changing climate continues to drive California weather to greater extremes.

For example: the bunnies. In 2014, riparian brush rabbits—transplanted years ago from Caswell to the national wildlife refuge on the other side of the San Joaquin River—were spotted on wildlife cams at Dos Rios. This was both good and bad news. The good: Dos Rios was part of their former range. Now that the plants they liked were here again, they were ready to move back. The bad: much of Dos Rios, like most modern farms, had been laser-leveled for the convenience of farm equipment. What was good for machines is bad for bunnies. The next time Dos Rios flooded, they could drown before they made it to higher ground. The San Joaquin National Wildlife Refuge was at such a low elevation that when floodwaters got too high, Fish and Wildlife had to go around in boats and rescue any bunny survivors stranded in trees. It made for cute photographs, but it was also depressing.

River Partners began pushing earth into giant mounds and planted them with native shrubs, like wild roses and blackberries, and grasses for cover. The next time a flood came, the bunnies found the mounds, which was great news. Then they ate all the shrubs and grasses that were their cover. The bunnies were now a raptor buffet, and it was back to the drawing board.

The crews replanted the mounds, careful to add some plants that were less tasty to bunnies. They began shaping the dirt again, this time into “bunny ramps”—long slopes leading from the lowest places up to the highest ones, where the bunnies would have room to roam. Moving dirt is expensive, says Austin. But it benefits more than the bunnies, since different species of plants are adapted to different levels of flooding: Cottonwood roots don’t need as much oxygen as other trees, and can survive being flooded for months. Elderberry bushes’ root systems can survive submersion for a little while but can’t make it through a long flood. Coyote brush roots, meanwhile, are happiest above the flood line.

We pass a clump of sticks poking out of the ground—baby cottonwoods filed to pencil points by a group of recently arrived beavers. We pass nervous-looking deer and a smug-looking coyote. “A lot of my dogbane survived, which is super exciting to me,” says Stevenot, gesturing proudly at a squat little plant. “You can see this one already spreading by rhizome.”

Dogbane is another valuable weaving material. It has some of the strongest cellulosic fibers of any plant—similar to hemp, but easier to work with. Like milkweed, which had a bad reputation before people realized how important it was to monarch butterflies, dogbane has been virtually eliminated from farm country because if livestock don’t find enough of the food they actually like, they’ll eat it out of desperation and make themselves sick. “You don’t want sick cows,” says Stevenot. “So the easiest way to deal with it is to just kill it.”

In 2021, three acres of Dos Rios were set aside specifically for permanent Native use. Austin got a wish list of plants from his mom and aunties, then narrowed it down to what was practical. “It was kind of a last-minute deal,” says Kimberly. “Austin says, ‘Mom, we got these plants.’ … Here I am calling people in the middle of the night—‘Hey, can you come over here? We got to plant this garden.’ ” Volunteers showed up from as far away as the Wilton Rancheria and Fresno, over an hour’s drive away.

The next year, Austin found a few sedge beds during a land survey. Kimberly and a group of other weavers began cleaning them up. They were absolutely full of ticks—unusual and possibly a legacy of there having been so much livestock nearby. A good controlled burn would fix that. Just take some dry grass, light it, and scatter it in places that need some low-intensity fire. Or, Kimberly adds, she does know a guy with a flamethrower.

Even in their messy, tick-filled state, the beds had a quality to them that she recognized. These had once been tended, a long time ago. Now they were going to be cared for again.

This story was corrected to reflect that the climate bond may be on the ballot in November 2024; it is not a certainty.