For archeologists, what defines people as human is how we bury our dead. Imagine, then, a society that relegates a whole community as legally inhuman, enslaved with no rights. In spite of slavery, African burial grounds are tangible reminders of the enslaved and free – defying oppressive circumstances by reclaiming people’s humanity through acts of remembrance.

When I first visited the British overseas territory of St Helena in 2018 and saw the burial ground in Rupert’s Valley, I was astounded by its size and significance. It unambiguously placed the island at the centre of the Middle Passage – tying the British empire to the institution of slavery in the US, the Caribbean, and globally.

During my time on the island, I spoke to many community and government stakeholders, who sometimes seemed hard-pressed to reconcile their sense of “Britishness” with acknowledging their history linked to the transatlantic slave trade.

I was brought there because of a similar struggle that began 34 years ago: to preserve a burial ground in the heart of Lower Manhattan, the New York African burial ground. I led the fight alongside many others to realise a monument honouring the memory of thousands of enslaved and free Africans.

Today, I am a global expert specialising in protecting and memorialising African burial grounds. Here are five other historical burial sites around the world. How we choose to remember these places matters. They are sites of reclamation and resistance, where revolutionary acts of remembrance will for ever mark our cultural landscape.

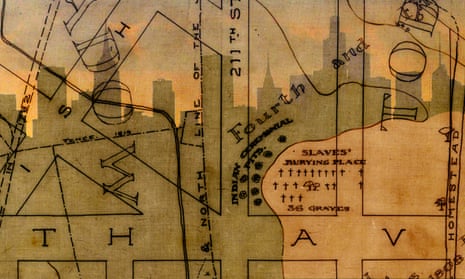

Inwood Sacred Site

New York City

The “Slaves Burying Place” held more than 36 enslaved Africans who lived and died in bondage to Dutch colonial settlers farming in northern Manhattan’s Inwood neighbourhood. Even in death, they were dehumanised by laws prohibiting their burial in consecrated grounds with their enslavers. A newspaper reported in 1903 the unceremonious excavation of the burial ground to make way for a road. Bones were reportedly taken for souvenirs and by the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH). When the site was marked for development, the Bowery Residents Committee (BRC) learned of the history and the injustice, with the desire for justice prompting a halt to further planning. Various stakeholders were engaged, including descendant communities of enslaved and Indigenous peoples, community residents, leaders, historians, and advocates, and the Dyckman Farmhouse Museum. Discussions for the repatriation of human remains from the AMNH and a memorial are under way.

Cherry Lane cemetery

Staten Island

Also known as the Old Slaves’ Burying Ground and Coloured cemetery, it was once owned by the Second Asbury African Methodist Episcopal church, torn down by vandals in the 1880s. The site was seized in 1954 under questionable circumstances and was paved over in the 1960s. A shopping plaza now stands where people were buried. More than 1,000 people were interred during the life of the cemetery, until 1916. The last person born into slavery on Staten Island, Benjamin Prine, was buried at age 99. His descendants now fight to repair the historical injustice and reclaim the site and the humanity of those lying there.

Farmer Street cemetery

Newnan, Georgia

Farmer Street cemetery, owned by the city of Newnan, Georgia, just south of Atlanta, was used for enslaved and free Black people. Newnan had a notorious reputation for the lynching of Sam Hose, who was accused of killing a white man during a dispute over money and raping his wife. Hose was captured, dragged from custody and lynched the next day without trial; his body was burned and dismembered, with parts given out as trophies. In 2021, community leaders protested against the City’s indifference to the site, organising a march from the cemetery to the town centre to deliver messages of protest at the foot of a Confederate statue. At the heart of the issue was the city’s neglect of the cemetery and encroachment by a multimillion-dollar skatepark. The city honours and maintains a Confederate cemetery, without according the same respect to the Black cemetery.

Golden Rock African burial ground

Sint Eustatius

In 2021 and based on a 1781 map of the island of Sint Eustatius, in the Dutch Caribbean, archaeologists excavated the remains of the former Golden Rock plantation quarters for enslaved Africans. Protests against the excavations by the community of Sint Eustatius led to increased awareness and attention to the island’s African cultural heritage. The controversial excavations generated a movement by descendants to research their past of enslavement, including making an inventory from archive sources of the inhabitants of African descent from the Golden Rock plantation. Community activists, including the St Eustatius Afrikan Burial Ground Alliance, have been instrumental in leading the charge and raising awareness as a way of reclaiming the sites and humanity of the enslaved people buried on private properties and public lands across the island.

Cotton Dike cemetery

Dataw Island, South Carolina

Cotton Dike cemetery, known as the “slave cemetery”, was located on the former Sams Plantation, which occupied Dataw Island, Beaufort, near St Helena, South Carolina. The Sams family exploited and forced African labourers to cultivate Sea Island cotton and indigo for Britain. The cemetery was used from 1785 to 1967 by generations of enslaved and free Africans. In 2004, possibly for a land-use survey, community stakeholders were interviewed amid plans to develop a “premier residential community and golf club”, further isolating the cemetery from any cultural connection. By 2007, the year the African Burial Ground National Monument opened in New York, Andrew Robinson, a Dataw native and New York resident, and his brother Nathan campaigned to raise a monument honouring their family in Cotton Dike cemetery. Signage was negotiated with the approval of Dataw Historic Foundation History & Learning Center, the designated steward of the site on behalf of the development, and a rededication ceremony was held. Access to the site is through a private residential development, which can isolate cultural identity and present challenges over who gets to tell this story.