Nature attracts and influences many artists in Finland. They seek out meditative moments of calm in the forest or choose studios located near nature areas. They often use or depict natural materials in their artworks: wood, clay, leaves, flower petals, or in one case even the wings of dead birds.

The artists in this article recount how their work reflects their thinking about biodiversity, ecosystems, land use and the relationship between humans and nature. They also examine modern society, human beings and questions of identity and community.

In studio visits and interviews all around Finland, 12 different artists tell us where their art originates, how they create it, and what they hope it will achieve.

Anni Hanén, visual artist

Photo: Minna Kurjenluoma

Visual artist Anni Hanén (born in 1981), often finds herself jotting down notes for hours on end while sitting under a tree or at the end of a pier, losing track of time. She is at her happiest when she’s out on the open sea, enveloped by solitude.

Her profound connection with nature stems from a happy, free childhood.

“I practically grew up in the forest,” she says. “I didn’t have a playground or a lot of friends or toys, but I knew every single tree, rock and stump in my forest. I was like a little forester by the time I ventured to school as a first-grader. My mother was concerned about my adjustment to real life.”

Small, by Anni Hanén.Photo: Minna Kurjenluoma

Hanén delves into childhood memories in several of her artworks. Her latest creations draw inspiration from a recently purchased plot of land where the original vegetation had succumbed to invasive species.

“I was influenced by the act of removing those invasive species and the changes it brought to my life,” she says. “It has been a cleansing and healing process. Now the rejuvenated plot flourishes with native plants, as well as those introduced by its former inhabitants.”

Hanén places great importance on her choice of materials. For instance, her cyanotypes, crafted using a 19th-century method, are printed on bedsheets that have been in her family since the early 20th century. Hanén enjoys the physicality of the process.

“When I immerse myself in the creative process and the world around me fades away, I truly feel like I am making progress,” she says.

Camilla Vuorenmaa, visual artist

Photo: Minna Kurjenluoma

Visual artist Camilla Vuorenmaa (born in 1979) seeks to capture the uniqueness and peculiarity of human beings in her work.

“The way humans impact their environment and the people around them is captivating,” she says. “Every individual is significant, and every person has a profound influence on their community. I’m intrigued by how interconnected we all are, how we function in a group, and how we act in order to fit in and avoid rejection.”

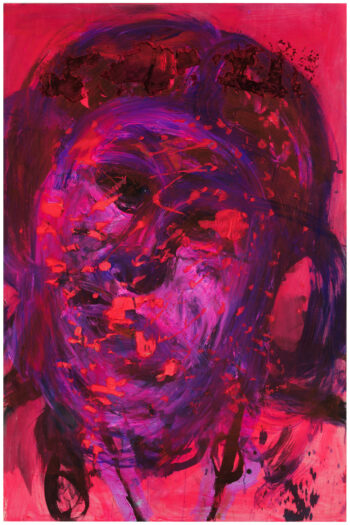

Dark side Leia, by Camilla Vuorenmaa© Kuvasto/2024; Photo: Jussi Tiainen

Vuorenmaa has delved into these subjects by exploring, for instance, the cultures of fishermen and athletes. She employs different materials and techniques in her work: painting, woodcarving and multimedia. She usually begins her journey by photographing her subjects.

“I select materials that suit the intended purpose and the emotion I wish to express in my art,” Vuorenmaa says. “There’s a strong physical aspect to wood and it has a pleasant scent. But it is also quite coarse.”

In contrast, canvas brings a softness that can complement certain pieces of art. Temporary, site-specific artworks play an important role, too. A piece with a shorter lifespan means less pressure for the artist.

Kihwa-Endale, painter and spoken-word poet

Photo: Minna Kurjenluoma

Kihwa-Endale (born in 1992) is a painter and a spoken-word poet. Her practice revolves around reflection and bridging different realities, which is why she commonly paints on mirrors.

“Whoever looks at the painting immediately becomes a part of that story as well, even if it is temporary, as they move past it,” she says. “I wanted to use mirrors because it implies that everyone’s stories are connected, regardless of their backgrounds.”

Helsinki-based Kihwa-Endale’s background is partly Korean and partly Ethiopian, and she has lived in different parts of the world. She recognises art and artistic venues as significant influencers for creativity, activism and community building.

The Bell Rings and We Are Someone’s Daughters Again (acrylic on mirror), by Kihwa-EndalePhoto: Minna Kurjenluoma

“When I decided to study art, I didn’t see myself reflected in the art that was taught in our school or the art spaces we would visit,” she says. “Sometimes this made it difficult to recognise that I am an artist, too.

“There’s so much potential for art spaces and artists to encourage more people to engage with their own creativity. I feel it is important to decentralise myself from my art, so that I can stay open to cocreating with others and with the environment around me.”

As an extension of her work as an artist, Kihwa-Endale started a community project called Kairos, which re-imagines art spaces and practises. It primarily organises a range of cultural events, from poetry circles to art exhibitions, in Helsinki, where different narratives can meet and explore artistic expressions.

Matti Aikio, visual artist

Photo: Minna Kurjenluoma

Sámi artist Matti Aikio (born in 1980) is also a reindeer herder. Reindeer herding is an important part of the Sámi culture, as are hunting and fishing.

The Sámi are the only recognised Indigenous people in the EU area. Their northern homeland, called Sápmi, is divided into four parts by the borders of the nation-states Finland, Sweden, Norway and Russia. In Finland, there are about 10,000 Sámi. They form a linguistic and cultural minority group.

In his art, Aikio explores the unique connection of the Sámi people with nature, a relationship that he believes contrasts with the perspectives of mainstream modern society. To Aikio, these differences in views are at the root of many conflicts.

“For Sámi culture to survive, it needs a connection to the land where it can be practised traditionally,” he says. “With fewer and fewer opportunities, we’re running out of places to go.”

Still photo from Oikos, a video by Matti AikioPhoto: Matti Aikio

Aikio comes from a lineage of strong Sámi advocacy; his father and grandfather have both fought for Sámi rights. Aikio’s art does not strive for activism or the mystification of Sámi culture – he aims to highlight Sámi issues by artistic means.

In his works, he combines moving images, sound, text and photographs. The lengthy work processes require a lot of research and gathering of material.

“My goal is to create art that gives the viewer the freedom to interpret it, but ideally it also offers the opportunity to change their perspective,” Aikio explains.

For example, the use of natural resources and construction projects related to fossil-free energy are processes that Aikio, like his fellow Sámi, regards as part of a long continuum.

“Our lands are seen as untouched, as no-man’s lands that can be continuously exploited,” he says. “The Sámi oppose the way projects are implemented.”

Paula Humberg, photographer and bio-artist

Photo: Minna Kurjenluoma

Photographer and bio-artist Paula Humberg (born in 1983) draws inspiration from the world of science and environmental conservation. Reading scientific publications plays a part in her creative process.

“Through art as a medium, I can immerse myself freely in biological research topics that I find fascinating,” she says.

She employs a variety of techniques in her art. For instance, microscopes are essential when portraying organisms invisible to the naked eye. While in Peru, Humberg used time-lapse videography to document moths, both in a nature reserve and near a residential area.

“Based on the images I collected, there are visible differences in the moth species in the two environments,” she says. “Those differences have also been found in studies.”

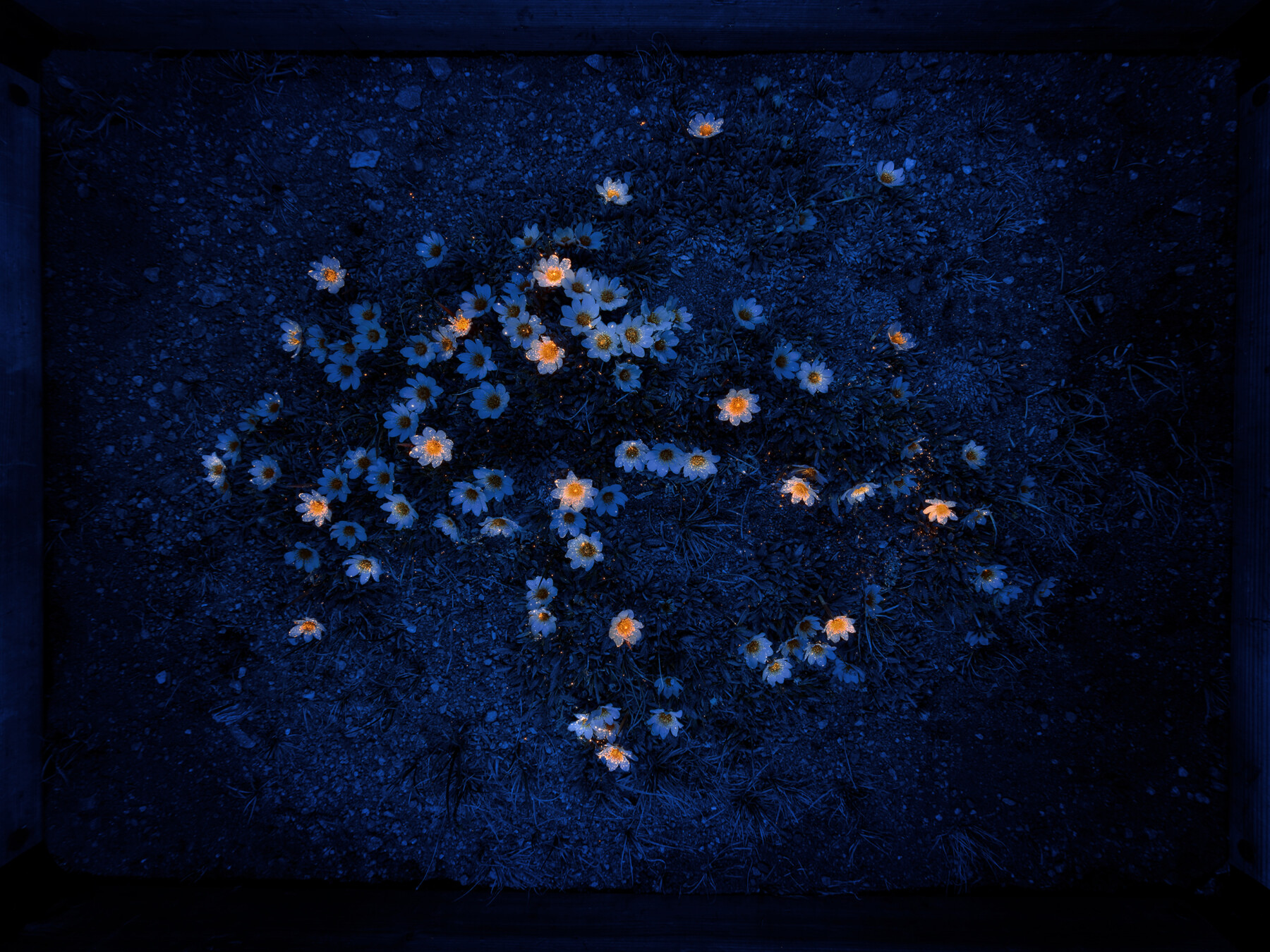

Dispersal: Slot A1 at 72h, by Paula Humberg© Kuvasto/2024; Photo: Paula Humberg

Humberg expresses particular concern about deforestation. Observations of specific species can offer insights into the ecosystem’s biodiversity.

While in Greenland, Humberg embarked on a collaborative project about pollinators with Finnish biologist Riikka Kaartinen. The number of muscid flies in the region has decreased greatly over the years.

They approached the topic by using a fluorescent pigment that comes alive under ultraviolet light, visually capturing the pollination. The experiment led to beautiful pieces of art with glimpses of mountain avens (a low-growing flowering plant) that seemed to be shining in the otherwise dark tundra.

“I felt a sense of accomplishment in Greenland, realising I had managed to bring together the worlds of biology and art,” says Humberg.

Paavo Halonen, contemporary artist and freelance print designer

Photo: Minna Kurjenluoma

Paavo Halonen (born in 1974) is a multifaceted contemporary artist and freelance print designer. In addition to his artistic pursuits, Halonen has left his creative mark by designing prints for Finnish textile and clothing brand Marimekko and creating sets for a popular baking competition show on TV.

“I’m deeply intrigued by various visual media and their potential to influence people,” he says.

In his contemporary art, Halonen relies on reused or discarded materials. He doesn’t want to produce more unnecessary items in the world.

“Used materials tell their own stories,” he says. “Coming from the countryside, I want to shed light on forgotten aspects of our fading folk heritage. I have used discarded utility items and I combined them with elements from nature.”

Don’t you ever, by Paavo HalonenPhoto: Minna Kurjenluoma

With global crises, the pandemic, and the war in Ukraine, his thinking has evolved further.

“I recognised that just praising nature is not enough,” says Halonen. “I sought the roots of our societal issues and other disasters, which led me to emphasise human responsibility for the wellbeing of nature and ourselves.”

Halonen draws inspiration and lessons from his travels and the people he works with. The numerous work projects bring balance to the otherwise rather solitary life of an artist.

“Drawing from my Lutheran roots and inspired by time I spent in Italy, I decided to bring religious symbols and saints into my work,” says Halonen. “For me, they represented humans in their clearest form.”

Enni Kalilainen, sculptor

Photo: Minna Kurjenluoma

The sculptures of Enni Kalilainen (born in 1976) resonate with depth and expression. She is captivated by clay as a material.

”It has its own semiotics and historical references that even lead us to the Bible and Genesis, in which God moulded the human from the dust of the earth,” she says. “I have even used it when naming some of my pieces, such as Shaped by the dust under our feet.”

Kalilainen’s sculptures, often portraying trans figures, might be different from what many consider ordinary. Yet her works seem to remind the spectator that these forms are just as valid. The need for recognition and acceptance is universal.

“It is great if my art can empower the queer community or transmit a message that parents can ideally pass on to their children,” she says.

It’s dust of the earth. It’s the silence of clay and smoke surrounding me., by Enni Kalilainen© Kuvasto/2024; Photo: Minna Kurjenluoma

While growing up, Kalilainen often found herself alone. As a trans child with a passion for art, she didn’t quite fit the mould of a small-town, working-class upbringing.

“Navigating through childhood, adolescence, and into adulthood was challenging,” she says. “Sadly, the situation for trans children remains bleak today.”

For Kalilainen, art has been a liberating force, allowing her to discover her path and express her identity. Beyond her artistic pursuits, she wears many hats: educator, advocate and even world-class skateboarder who has competed at the World Cup level.

“My life has been filled with nuances,” Kalilainen says. “I have managed to find fulfilment, even though the path hasn’t been easy.

“People are multifaceted. I often sense that others try to box me in with specific labels or perceptions, which is truly a pity.”

Veera Kulju, sculptor

Photo: Minna Kurjenluoma

Sculptor Veera Kulju (born in 1975) finds solace and serenity in nature. There, she feels a deep connection to the world around her, a sense of belonging to a larger, coherent entity.

“Even though nature is never flawless, it’s perfect and understandable in its own way,” she says. “It makes you appreciate the delicacies and vulnerabilities within yourself.”

Kulju’s ceramic pieces depict detailed creatures of the plant world, with petals and needles. The artist sees herself as creating primeval forests out of clay. For her, preserving the forests in their natural state is crucial.

“The ecosystem and nature’s ability to seek balance is a miracle,” she says. “We should understand and respect it, and aim to be in harmony with it.”

The King of Gresa, by Veera KuljuPhoto: Chikako Harada

Kulju’s art always stems from her emotional state of mind. Her late mother’s struggle with Alzheimer’s disease had an influence on her work, which ponders themes of relinquishment and the essence of being.

“I aim to be very present in my works and in strong physical contact with them,” she says.

Her upcoming works include ornamental mirrors that are inspired by fairy tales, fantasy and magic. In today’s world, we need hope and playfulness in our lives.

“My mirrors are a path to consciousness and to my relationship with nature, but they can also be paths to our imaginary worlds,” says Kulju.

Anni Rapinoja, visual artist

Photo: Minna Kurjenluoma

Anni Rapinoja (born in 1949) creates her pieces on the tranquil northern island of Hailuoto, where her family has thrived for 400 years.

“I want to awaken people to the ever-changing splendour of nature, and to human beings as a part of that,” she says.

With an education in natural science and geography, Rapinoja finds her inspiration in nature.

“Nature is my coworker, and it has taught me patience,” she says.

Children of Icarus, by Anni Rapinoja© Kuvasto/2024; Photo: Minna Kurjenluoma

“For me, working means walking, researching, collecting, drying, pressing, searching for forms, discovering, and creating. Making a piece of art can take years, and it can change and continue to evolve.”

One of her most famous collections is The Wardrobe of Nature, showcasing enchanting shoes, bags and coats made of lingonberry leaves, cottongrass, reeds and catkins. These “down-to-earth” clothes and accessories have brought the wilderness close to viewers all over the world.

“The mould of the shoe is sculpted from rice paper and rye porridge, later coated, then lined with bright green lingonberry leaves,” says Rapinoja. “Over the years, the colours gradually change, transitioning through shades of grey-green to beautiful browns, dark browns and almost black. I aim to feature an array of these transforming shoes in all my exhibitions.”

Rapinoja’s message is clear: Nature is diverse and perpetually changing. Humans are part of nature. What we do to nature, we also do to ourselves.

Erno Enkenberg, visual artist

Photo: Minna Kurjenluoma

Erno Enkenberg’s (born in 1975) artworks are like scenes from movies or video games, feeling both a sense of familiarity and otherworldly. Through their theatrical illumination, the pieces masterfully blend reality with imagination.

“My pieces try to interpret humanity through the means of art – who we are and what our search for identity is made of,” he says.

Previously, Enkenberg started his creative process by creating self-made, illuminated paper models based on his ideas. He would then photograph these models and use the images as sketches for his paintings.

Leash, by Erno Enkenberg© Kuvasto/2024; Photo: Erno Enkenberg

“The images in my mind are spatial rather than flat,” he says. “Creating a 3D model that represents my vision is a natural extension of my inner world.”

Today, Enkenberg has transitioned from paper to making digital 3D models, which allows him to play with images and light more freely.

“Working in a digital environment is liberating,” he says. “I am no longer bound by the constraints of physical models.”

Inspiration often strikes Enkenberg on his sofa, while he is reading books or watching movies or TV shows. His most recent pieces highlight the individual as the agent of their own life.

The artworks “reflect life on social media,” he says. “We are constantly presenting ourselves for the perceptions of others. We all have our stage and our audience. We are all performers in the theatre of our own lives.”

Nayab Ikram, visual artist

Photo: Minna Kurjenluoma

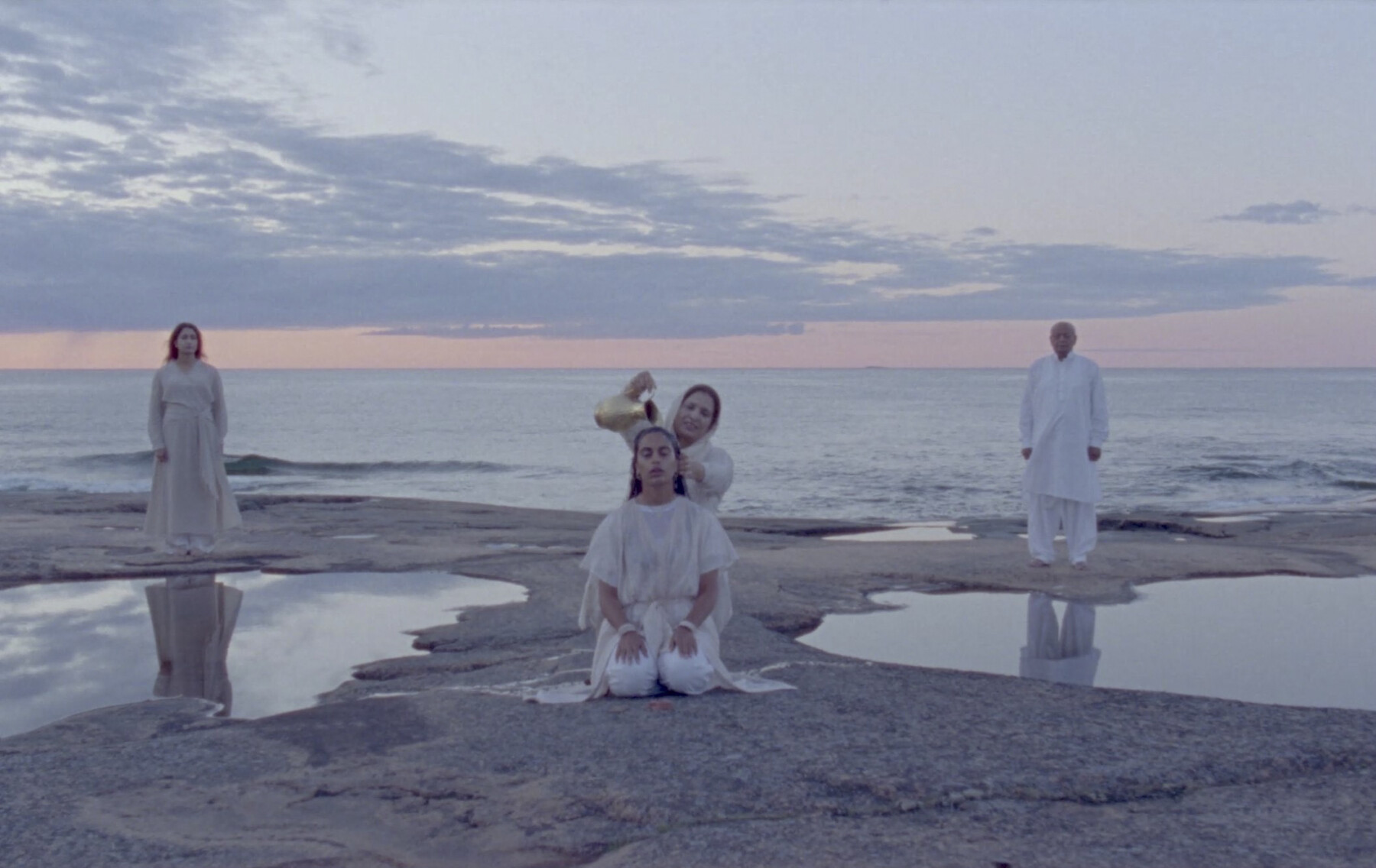

Nayab Ikram (born in 1992) is a photographer and visual artist from the Åland Islands, a picturesque, autonomous Swedish-speaking archipelago that is part of Finland.

She taps into a rich cultural blend of her Finnish surroundings and her Pakistani heritage. Her art toggles between the playful and the profound, with a keen focus on cultural identity. Her creations stem from her personal observations and experience of navigating two worlds.

“I think that most people who have a similar background to mine might recognise the feeling of in-betweenness, the navigation between cultures, emotions and surroundings,” she says.

Photography became Ikram’s voice at an early age. It was an expressive outlet for emotions that words could not capture. Today, her work delves deep into cultural symbols and rituals, discovering surprising similarities between the cultures of Finland and Pakistan.

Still photo from The Family, a video by Nayab IkramPhoto: Nayab Ikram

“When you look at history and symbolism, you can see that the same kinds of rituals happened in parallel in different cultures and countries,” she says. “I find that very interesting, considering that today’s society and media want us to think that these cultures are vastly separate.”

Her playful side is vividly displayed in Symbiosis (2022), which is on permanent display at a primary school in Helsinki. The piece, which features photographs of hands playing with colourful modelling clay, embodies freedom and creativity.

“As a material, clay doesn’t have any rules,” says Ikram. “The children can create their own future and their own rules as they go, because they are our future.”

H.C. Berg, artist and sculptor

Photo: Minna Kurjenluoma

The award-winning artist H.C. Berg (born in 1971) embraces life and its opportunities with enthusiasm. He believes that a positive attitude leads the way to successful creative work.

In shaping his masterpieces, Berg employs new technology and a diverse palette of materials, including steel, acrylic, glass, ceramics, and plastic components.

“In the modern world, the traditional perspective on art can sometimes feel more like a cage than a possibility,” he says. “To truly find oneself in this new age, it’s essential to challenge the thinking of the past.

“The digital world certainly adds excitement to your work; you always discover something new. There’s a feeling that nothing is ever truly finished.”

Nereidi, by H.C. BergPhoto: H.C. Berg

Berg’s colourful works play with observation and reality: a piece may appear entirely different from one angle to another.

“Our perceptions of our human identity can sometimes be too rigid,” he says. “The realities are very personal. How we see and experience things and describe our observations depends on our own experiences in life.”

Berg lives and works in the tranquil countryside of Inkoo, a stone’s throw from the bustling heart of the capital, Helsinki. He cherishes the light and silence of his surroundings.

“Such contrasts are the wonderful aspects of Finnishness,” he says. “A short car or train ride can transport us to a completely different dimension from city life. Every Finn possesses a global spirit, comfortably navigating urban settings. Yet, we all have an almost shamanistic Finnish soul, one that resonates with nature – foraging for mushrooms, picking berries and fishing.”

By Helena Liikanen-Renger, March 2024