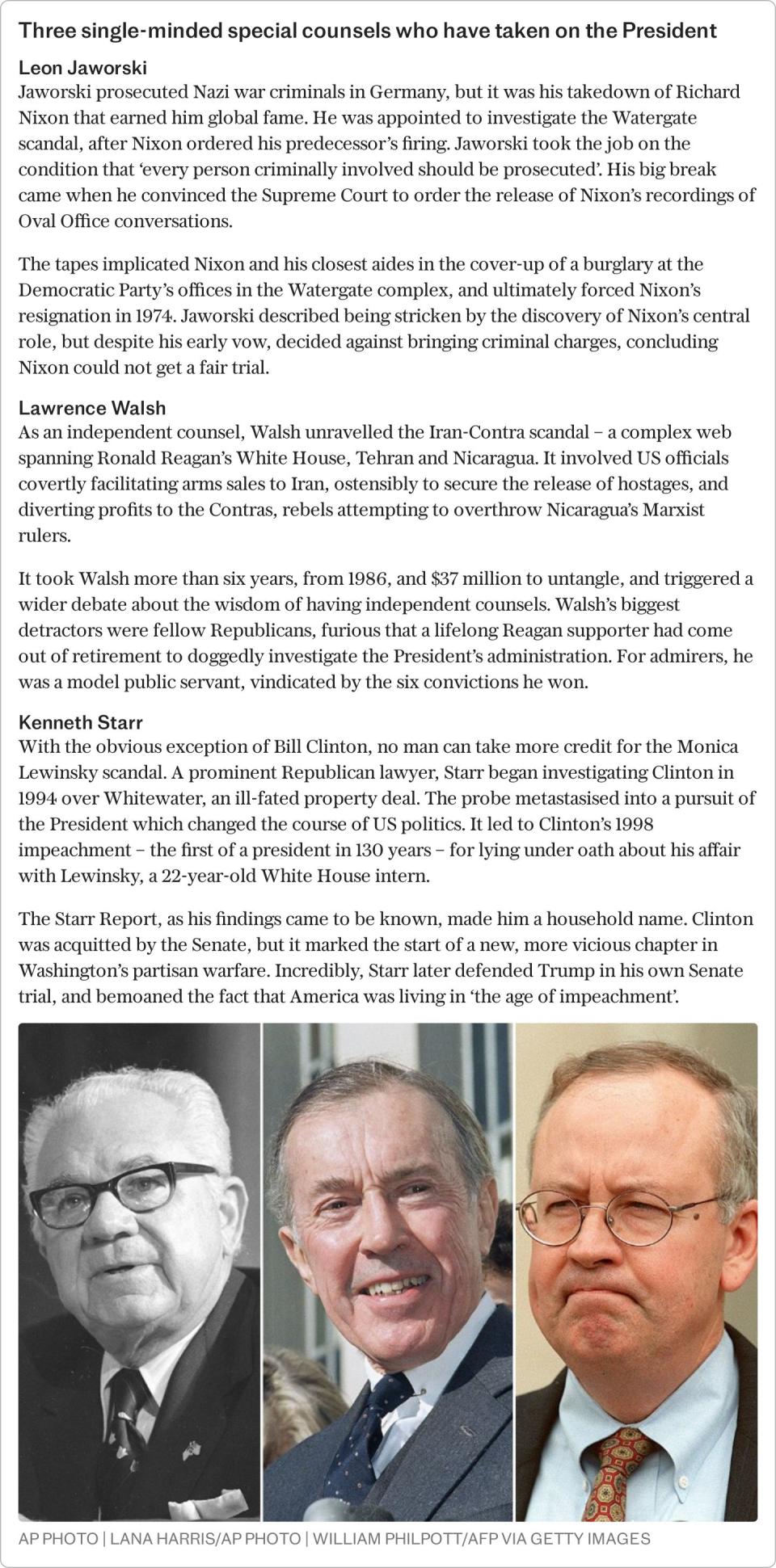

There’s one man in the way of Trump’s return to the White House – and it’s not Biden

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

As the polls stand, the greatest impediment to Donald Trump’s return to the White House in 2025 is not its current occupant, Joe Biden, but the spectre of a criminal conviction. The man working to secure just that on behalf of the US government, Jack Smith, a grizzled, taciturn career prosecutor, has cut an elusive figure since he emerged from the Department of Justice’s (DoJ) nondescript offices in Washington last June to announce he was indicting a former president for the first time in its history.

If the indictments – the first for allegedly mishandling US secrets, the second for attempting to overturn the 2020 election – were a political maelstrom threatening to split the country, Smith himself presents as decidedly muted.

With his stern demeanour and dark suits, the 54-year-old would be indistinguishable from any other smartly dressed, but restrained, federal prosecutor were it not for his thick salt and pepper beard.

The facial hair, like the man behind it, has become an object of fascination, only intensified by Smith’s long-standing reluctance to give interviews.

Smith, who would rather his court filings speak for themselves, even limits his press conferences to a matter of minutes. But his aggressive attempt to ensure Trump’s trial happens before the presidential election has catapulted him into the 2024 campaign, drawing detractors and admirers in equal measure.

While Trump, 77, saw an instant bump in both popularity and cash from his indictments, poll after poll has found that a conviction would harm his support among independent voters, a critical constituency, and even discourage his most ardent supporters.

Trump, who denies any wrongdoing, has dubbed Smith ‘deranged’ and a ‘Trump hater’ and attempted to derail the proceedings by claiming to have enjoyed broad immunity as president.

In response, Smith made a dramatic intervention to the Supreme Court in a bid to keep his spring trial on track. Acknowledging he was making an ‘extraordinary request’, he stressed the public interest in ensuring Trump faces accountability for allegedly attempting to subvert the last election before the next one takes place. ‘Nothing could be more vital to our democracy,’ he said.

The Supreme Court announced late last month that it would take up the question of Trump’s immunity in April, but ordered the election interference trial be put on hold in the meantime.

It represents a victory for Trump, who may be able to push off the trial until the summer at the earliest, or perhaps until after the election. In consequence, Smith has requested that Trump’s classified documents trial, which relates to his actions after quitting the White House, takes place over the summer. It means Trump’s first criminal trial is likely to be on state charges, rather than federal. He is scheduled to begin trial in New York on 25 March for allegedly falsifying business records relating to hush-money payments to women before the 2016 election, charges which he denies.

While Smith’s efforts have inspired fan memorabilia, a podcast series and even an entry into the Bobblehead Hall of Fame, they have also made him a target, deemed grave enough that he does not appear in public without a security detail.

There are few more equipped to handle the pressure. A man who has proved his mettle prosecuting war criminals and New York’s notorious mobsters is not easily cowed. Prior to leading the investigation into Trump, Smith served in The Hague as the chief prosecutor of a special court investigating crimes against humanity in Kosovo in the late 1990s. A triathlon enthusiast, Smith would routinely bike to his office, according to former colleagues, rather than make use of a driver or bodyguards typical of other senior officials.

Smith caused shockwaves in 2020 when he indicted Kosovo’s President, Hashim Thaçi, an ally of the West, on the eve of his attendance at a peace summit Trump was due to host at the White House. The ongoing trials on war crimes of Thaçi and his co-defendants, who all deny any serious charges, could rewrite the history of the Kosovo War, in which Nato forces intervened following atrocities by Serbian forces.

In his closing arguments in another case before the special court, Smith alluded to the uncomfortable questions his indictments have raised: ‘As a prosecutor, it is beyond my remit to argue to you or decide what wars were just and what wars were not. But I can say with conviction that war crimes on one side do not justify war crimes on the other side.’

It was this steely disposition, and his reputation for being ‘impartial and determined’, that led Merrick Garland, America’s Attorney General, to appoint Smith as the special counsel to handle Trump’s case. It handed Smith sweeping powers, and the unenviable task of deciding a question that the DoJ had been wrestling with since Trump left office in 2021, hot on the heels of the deadly Capitol riot many viewed as the culmination of his failed efforts to cling to power. Half the country felt letting Trump’s actions go unchallenged would undermine American democracy. The other half felt pursuing him would set a perilous precedent, and further strain the country’s already fraught social fabric.

In an atmosphere ripe with mistrust, the DoJ knew its next steps would find it on trial in the court of public opinion.

While Garland, the understated US Attorney General, is known as a cautious operator, Smith certainly presents as one willing to take a gamble. And yet, Smith’s decision to bring a federal indictment, and with it to plunge the US into uncharted waters, was far from inevitable, say those who know him best.

‘It’s important to remember that when he took on the role, there was no predetermination. I think that’s the way he approached it,’ says Kelly Currie, who worked alongside Smith at the US Attorney’s Office in Brooklyn for several years. Smith, who is not registered with any party, is ‘just not a political person’, says Currie. ‘He’s never approached his job that way.’ He added: ‘Had he viewed the evidence [against Trump] to be insufficient, he would not have hesitated to say so.’

Smith set out his own guiding principles back in 2010, when he was appointed to lead the DoJ unit which dealt with the thorniest issues, cases involving corrupt politicians. He took over at a turbulent time and was swiftly forced to defend his decisions to pursue, and in numerous cases not to pursue, investigations into high-ranking Democrats and Republicans.

‘If I were the sort of person who could be cowed,’ he told The New York Times at the time, ‘[If I thought] “I know the person did it, but we could lose, and that will look bad” – I would find another line of work.’

His approach, he said, was grounded in serving people like his parents, and his neighbours in his hometown of Clay, in upstate New York: ‘They pay their taxes, follow the rules and they expect their public officials to do the same.’

If Smith’s upbringing was not exactly humble, it is relatable for many Americans. Born John ‘Jack’ Luman Smith in 1969, he was raised in a three-bedroom house whose clapboard exterior, neat driveway and front lawn blended in on a quiet street nestled between two churches. He attended the nearby public school, where former classmates remember him as cheerful, funny and interested in sports.

As a tall and skinny teenager, he spent more time on the bench than the pitch for his American football team at Liverpool High School. But, as his old coach George Mangicaro fondly recalled, he would show up for every game to cheer on his teammates – a quality his colleagues say has characterised his professional life. It was at New York’s State University at Oneonta that Smith really flourished, maintaining high marks throughout his four-year political science degree, graduating in 1991.

While Smith’s former friends remember him fondly, not many are willing to speak publicly in such polarising times. One of the few to have done so, Scott Hanson, told a local upstate New York paper last year that he would never have guessed what the future held for his school peer. Though undoubtedly bright, he had never considered Smith a serious student and was surprised when his old friend told him he had won a place at Harvard University after scoring in the top one per cent of law school applicants.

Leaving Harvard in 1994, Smith could easily have followed the popular circuit between the Ivy League and lucrative law firms. Instead, he began his career in the respected, but far more gritty, Manhattan district attorney’s office under the tutelage of its legendary leader, Robert Morgenthau. In an era of New York mobsters, prosecuting violent crime cases became Smith’s day-to-day. ‘There were 40 or 50 of us who started together and all of us thought we wanted to be trial attorneys,’ he recalled years later.

He was one of the few to survive the baptism of fire as a courtroom novice, but modestly attributed his success to application, rather than skill. ‘I don’t think I was very talented,’ he said. His work ethic frequently merits mention among former colleagues, no shirkers themselves. ‘He’s one of the first people in the office at the beginning of the day, probably after he’s already ridden his bike for 40 miles or gone for a long run, and he’s still there at 9 or 10pm,’ said his former colleague Currie.

Smith became known among colleagues for waiting to go to their favourite sandwich shop until its two-for-one deal kicked in. ‘He was pretty disciplined about what he ate, but he was famous for being the half-price sandwich guy at nine o’clock at night,’ said Currie.

Smith’s dedication led him to spend a weekend camping out in a hallway to convince a domestic violence victim to testify. After ‘a long, long talk’, Smith said, she ultimately took the stand.

Having cut his teeth in Manhattan, Smith moved in 1999 to prosecuting federal cases at the US Attorney’s Office in Brooklyn, one of the most prestigious in the country. It was here, prosecuting one of the most heinous police abuse cases New York had ever seen, that he first garnered national attention.

Abner Louima, a Haitian immigrant, had been beaten and raped with a broken broomstick that perforated his rectum, bladder and colon while handcuffed by white officers in the late 1990s. The first attempt to secure a conviction against one of the officers, Charles Schwarz, was overturned on appeal. Amid national outrage, prosecutors readied for a second attempt in 2002.

Alan Vinegrad, the US attorney at the time, had his pick of talented lawyers to assist him. ‘I chose Jack based on his background,’ he said. ‘He was an outstanding trial lawyer: very comfortable in the courtroom, very effective.’

Vinegrad said he had watched Smith prosecute two corrupt officers in a case in Brooklyn and been impressed by his skills with juries. He was ‘smooth, confident’ and could connect with lay people better than most lawyers Vinegrad knew. He was also a ‘dogged investigator’.

Vinegrad’s choice was rewarded: with the aid of Smith, he secured Schwarz’s conviction. ‘He is a hard-nosed guy,’ Vinegrad says of his former protégé. ‘It’s been 22 years and look at his record, look at what he’s done with his life. He is a public servant committed to the cause of justice. A very formidable prosecutor.’

Vinegrad has no doubt that Smith will be drawing on his courtroom talents to meticulously prepare the team he has assembled for Trump’s trials. His top lieutenants, Raymond Hustler and David Harbach, are both close former colleagues. Described as a team player, Smith is known to be a fan of holding ‘mock trials’ to run through his subordinates’ opening statements. He then critiques their presentation and line of argument, to see if it ‘holds water’.

Smith does not speak in court in the two cases he has brought against Trump, trusting his clean-cut, sharp-suited deputies to make the government’s case. But he regularly attends the proceedings in a show of camaraderie, sitting in the first row of the public gallery and frequently staring intently at the former President.

Smith’s silence, in court and out, is a recognition that, in such a politicised environment, even the most innocuous statements can become ammunition. It is a strategy that has paid dividends. Trump, adept at skewering his opponents, has yet to find a nickname for Smith that has stuck. Instead, he has focused on attacking Smith’s wife of 12 years, Katy Chevigny, with whom he has an 11-year-old daughter.

Chevigny is a filmmaker who produced Becoming, a Netflix documentary about Michelle Obama, and donated to Biden’s 2020 campaign. Smith’s former colleagues say he is well versed in tuning out ‘distractions’, and insist the circus around him will not shake his focus.

Since Watergate, independent prosecutors have probed the presidencies of every commander-in-chief except Barack Obama and, while some emerged relatively unscathed from the encounters with their investigators, others found their presidencies consumed by it. There is no blueprint for prosecuting a former US president running to regain the mantle, but Smith’s actions so far suggest he is determined to foil Trump’s delay tactics.

If Trump wins a second term in November’s election before his prosecution can conclude, it will effectively doom Smith’s case, since presidents enjoy immunity while in office.

Yet for Smith, simply bringing these historic indictments may offer satisfaction in itself. Describing what impression he hoped to leave, he once said: ‘I want to devote my energies to making the world and my community a better place for my daughter to grow up in.’