Marbles ignite a war in beachcombing

A Revere man has become the attack leader against sea glass collectors who are “seeding” marbles, throwing them into the sea so they can be transformed and found again.

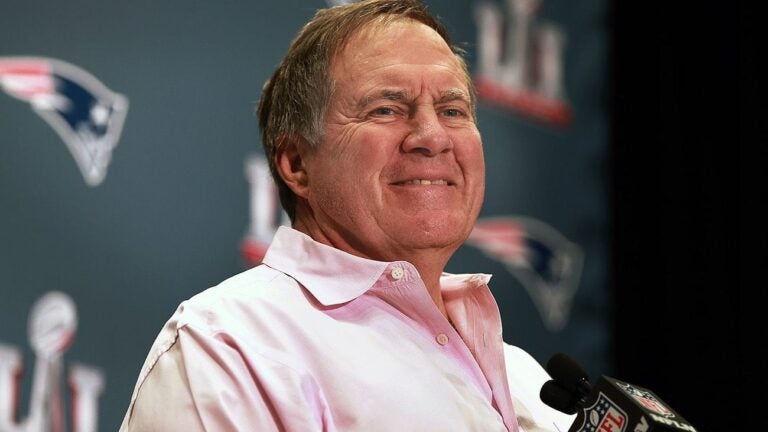

GLOUCESTER — Dave Valle, the bad boy of New England sea glass hunting, does not debate; instead, he attacks those he disagrees with, which is anyone he sees as cheating him, and all “purists,” out of the serendipity they chase.

The target of his war is specific: seeders, and anyone who condones the practice of intentionally throwing glass into the ocean so that it can be tumbled by swells and rediscovered in the future, transformed. But it is a particular kind of seeding, one that has grown in recent years, that triggers the rage in Valle that got him kicked out of three Facebook groups — marbles.

“A marble is supposed to be the most exciting thing to find beachcombing. It’s the ultimate treasure,” he said as he hunted a field of beach pebbles on a recent day, holding a walking stick with a spade fashioned to one end. “They say they’re leaving this for the future? It’s littering. And it sucks the magic out of it. Who wants to find a marble someone threw there?”

Sea glass collecting has exploded lately, buoyed by Facebook forums, a thriving market for sea-glass jewelry and crafts, and an older fanbase who embraced safe ways to be outside during the pandemic. When seeding marbles became a trend — Valle said it was a few people in Rhode Island who started the local fad a few years ago — it spread so quickly that a marble went from a once-in-a-lifetime find to once-a-day for some hunters. “Those people are full of it,” Valle said.

When one person shared a photo of 40 marbles found in a single day, Valle lost his mind and created his own private group, Don’t Worry Be Glassy, exclusively for dedicated “purists” like him. Now 55, Valle has been a serious hunter and crafter — he sells popular sea glass Christmas trees — for just the last decade. But he entered hard and went harder when marbles started making regular appearances. “Even if they didn’t seed them, they knew they were there.”

His approach offered no compromises, and among the people he clashed with was Stephen Hopkins, who created the largest online group in the area, the 29,000-member “New England Sea Glass Searchers!”

“Dave’s angle is to say he only has the pure stuff,” Hopkins said. “But then you’d have people say something like they found some glass that wasn’t cooked yet on a beach where kids play, so they moved it down away from where they play, and he’d go after them and say that’s seeding.”

But it isn’t just Valle who is outraged about seeding. Hopkins’ forum no longer allows it to be discussed because the arguments are heated and endless. Still, there are those like Mary McCarthy, a Maryland beachcomber who has written and lectured on the cheapening effects of seeding, who want the pressure to remain on until it becomes unforgivable.

“Its most significant sin is the loss of provenance,” she said. “Beachcombers find stuff on beaches that is there for a historical reason. They’ve done the research and know there was a resort or a ferry or an amusement park or a dump, and you find things that tell that story. Throwing marbles is Easter egging. It’s artificial.”

McCarthy travels to sea glass festivals all over the country, where she will examine finds to help people trace their story. “And I spend too much time informing people their precious marble was purchased two years ago at a Michael’s.”

The arguments for seeding, proponents say, would go like this: Sea glass is a diminishing resource. The good stuff has been picked. Plastic has taken over, and modern glass is much thinner and incapable of being tumbled for the decades it takes to get that warm and frosted look caused by the intrusion of moisture into the surface and the conditioning from being bounced around. They refer to the new stuff as “trash glass.”

And the intrusion of the market — sea glass jewelry and crafts can fetch big bucks, as can the sale of the raw materials to the artisans — has created a demand with limited supply.

Marbles, as well as the flatter spheres used as vase fillers, have proven to be perfectly designed to “frost” quickly, especially on the rocky coast of New England, where they are shaped to tumble and, maybe one day, make it to the beach.

“Especially in Massachusetts and Maine, you can get a decent frosting in a few years as opposed to a few decades,” said Richard LaMotte, the author of two prominent books on sea glass. “It does feel a little like cheating, but they’re not harmful or hazardous, and I think about little kids who might never find a marble. That’s a memory maker. But pouring gallons of marbles is overdoing it.”

In the past, marbles found their way into the ocean courtesy of children who, for decades, played a game where they used their thumb to “shoot” a marble at an opponent’s marbles and knock them out of a circle, a game often played at the beach. Boardwalk amusement parks were another seaside source. They were also sometimes used under railroad tracks. But perhaps the biggest supply comes from the marble used as a stopper inside a popular glass bottle that was for decades, starting in the late 1800s, one of the most economical ways to seal carbonated drinks.

“For my generation, finding a marble was the siren song, this remarkable luminous little treasure, the gateway drug that drew people in,” said Deacon Ritterbush, who is well known in the subculture as Dr. Beachcomb. “But now it’s capitalism gone wild. People grab everything they can find and don’t leave anything behind. And if they’re not selling it, they’re in a rush to show their haul on social media.”

The International Sea Glass Association, which requires its member artisans to keep sea glass in its natural, unaltered state — no cutting, sanding, or grinding — does not have an official policy on seeding. But César Williams-Padín, the organization’s president, said it is strongly discouraged.

“Sea glass tells a story, but with seeding it takes away that excitement and history,” Williams-Padín said. “There’s plenty of glass in the ocean. It doesn’t need more. And glass is going to continue to end up in the ocean without us adding to it. It’s unnecessary.”

The other big argument on the forums is about secrecy. This is Valle’s other passion. He has no interest in telling the internet where he gets the big hauls he posts about, and says he loves “bullying the bullies” who think that he is selfish for not sharing.

Valle grew up in Roslindale, went to Nantasket Beach as a kid, and now lives on Revere Beach. In person, he definitely still wears that street kid chip, but comes across softer than the attack dog online.

“I play it up, but this is my church. I call it my Sunday church. I listen to music. I find these beautiful things that tell a story. Look! Right here,” said as he used the spade to pick up a piece of green glass. “This is a piece of a Coke bottle from the 20s or 30s. They called it seafoam green. You see this everywhere.”

He has so much of it he doesn’t take it and returns it to where it was. He finds a few frosted white pieces he will use in future crafts, as well as a shard on which he can read the letters LV, which he will investigate later. But he gets very excited when a reporter finds a well-tumbled chunk of “bonfire glass,” a smooth gnarled glob from a bottle that was in a fire.

“We’re keeping that, that’s great. That’s what we hope to find,” he said. “You don’t need marbles for this to be magic.”

Conversation

This discussion has ended. Please join elsewhere on Boston.com