Confessions of a Moll: A Boston Gangster’s Long-Time Girlfriend Speaks

Twenty years ago, Stephen “The Rifleman” Flemmi pled guilty to 10 counts of murder. Now, for the very first time, the notorious mobster's former companion tells her story—and what she’s realized in the decades since.

Shirley Grispi (neé Rogers) was just 20 years old when she embarked on a decade-long romantic relationship with Stephen Flemmi, a violent Boston gangster. Unlike Grispi, some of his other girlfriends didn’t live to tell their stories. / Photo by Michael Adno

When Shirley Grispi walked into a room, heads turned. Lots of them. But on that day in 1969, when the fit, tanned knockout strode into T.F. Green, then a little-used, second-tier airport, she was working hard not to call any attention to herself. Her bleached-blond locks had been tucked under a brunette wig. Her long, fluttering eyelashes and deep-brown eyes were hidden behind the lenses of large horn-rimmed glasses.

She made her way to the counter and, as instructed, retrieved a plane ticket that had been left for her, glancing over her shoulder to see if anyone was following her. It appeared that the federal law enforcement agents who had been looking for her were nowhere to be found. Then she made her way to the gate and boarded a flight to Los Angeles.

Seated next to Grispi was a priest. As he said hello and started to chat her up, she felt a sharp cut of shame. After all, she was an Irish-Catholic woman on her way to see someone she knew no priest would ever approve of. Grispi closed her eyes and fell asleep for most of the flight. She woke up just as the plane was descending.

Stubbing out her cigarette in the armrest ashtray, she stood up from her seat and walked out of the smoky cabin and down the concourse, her heels clicking rhythmically on the tile as she made her way to the luggage carousel. She watched bag after bag pass by her on the conveyor belt until she heard a deep whisper behind her: “Hey lady, I almost didn’t recognize you.” Grispi spun around to see Stephen Flemmi standing behind her, grinning. Her heart leaped out of her chest.

At that time, Flemmi, known as “The Rifleman”—a nickname he’d had since the Korean War on account of his marksmanship—was already a notorious Boston gangster. Even though he was still years away from the moment when he’d team up with Whitey Bulger to run Boston’s underworld, he was already a wanted man. He’d fled to L.A. after a crooked FBI agent tipped him off that he was about to be indicted for a car bombing that had nearly killed a lawyer and the 1967 murder of William Bennett, whose body was found in a Dorchester snowbank with a gunshot wound to the chest.

To Grispi, though, Flemmi was something else entirely. She threw her arms around the gangster’s neck and planted a kiss on his lips. For the past nine years, she had been Flemmi’s moll, as gangsters’ girlfriends are known. Throughout the 1960s, a decade known in Boston for its deadly and terrifying gang wars, Grispi had an intimate view of a notorious criminal operating in the city’s underworld and his interactions with his mentors, who would also become his targets. This story is based on facts alleged by Grispi in an unpublished memoir and during this magazine’s numerous interviews with her.

In the years after their relationship ended, two of Flemmi’s lovers would also become his victims. Grispi managed to survive not just a decade as Flemmi’s girlfriend but also leaving the jealous killer for another man in 1972. Now, some six decades later, at age 84, she is telling—for the very first time—her story of living in danger with Flemmi.

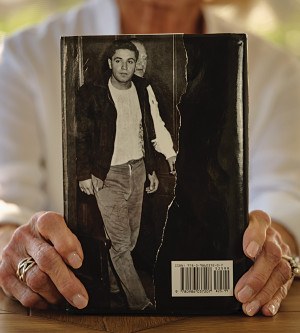

Shirley Grispi, shown above holding a picture of a younger version of herself, survived her relationship with Flemmi and went on to marry someone else. Some of Flemmi’s other girlfriends weren’t so lucky. / Photo by Michael Adno

Shirley Grispi, née Rogers, first met Flemmi through the man she was engaged to marry. It was 1960, and she was just 20 and well known in the South End, where she and her fiancé owned a gas station on the corner of Albany and Dover streets. It was rare during that era to see a woman pumping gas, and the sight caught people’s eye, especially given Grispi’s good looks. One day, a photographer from the now-defunct newspaper the Boston Traveler took a picture of her filling someone’s car; after it ran in the paper, cars lined up on Dover Street (now known as East Berkeley Street) waiting for gas—and a glimpse of the gal pumping it.

Grispi had also made something of a name for herself by racing cars at the Norwood Arena. After helping her fiancé soup up his car and then watching all of his races, one day, after lots of nagging, she finally convinced one of the track’s bigwigs to allow women to race. The day of the Powder Puff Derby, Grispi showed up directly after an appointment at the hairdresser wearing lipstick and designer jeans, to the jeers of her leather-jacket-clad, short-haired female competitors, who called her “fancy pants.” She put on her helmet, climbed into her car, and beat them all in nine races that day.

Grispi became a legend. Even Flemmi had heard about her conquests. Yet somehow, Grispi had no idea who Flemmi was, even though by then, he was a lot more well known around town than she was—and not for anything good. He had a reputation as a loan shark, a wise guy, and a ladies man.

The first time Grispi learned about Flemmi was when he started showing up at the gas station asking for her fiancé. She soon learned why: Her fiancé told her that he owed Flemmi hundreds of dollars, a substantial sum in those days and, more important, about half of the nest egg he and Grispi had squirreled away for their wedding. He told her he had a gambling problem, but she didn’t buy it, so she arranged to meet Flemmi to find out more.

It was 8 p.m. when Grispi strolled into the Dudley Lounge, a Flemmi-owned gangster hangout in Roxbury, wearing a slinky miniskirt with her hair in a blond beehive. A waitress yelled to her from across the bar. “Are you Shirley?” she asked. Grispi nodded her head yes. The waitress waved her over to a rear booth. “I’ll tell Stevie you’re here. Whaddya want to drink?”

She had hardly sat down when a nasty-looking man in a leather jacket, smelling of whiskey, cigarettes, and cheap musk, approached her. “Hi there, you cute little thing; what are you doing sitting here all by yourself?” he asked.

Before she could answer, Flemmi appeared right behind him. He tapped the man on the shoulder and, with a look that could kill, said, “Hey Kevin, you got a problem?”

The man put his hands up in the air instinctively. “No problem at all,” he said. “Sorry, Stevie.”

“Get lost,” Flemmi replied, sending the guy scrambling.

Flemmi lowered himself into the booth next to Grispi. Then he peered deep into her eyes and said in a low-pitched voice: “Hi, beautiful. I’m sorry about that. Wow, you look great.” She felt an instant attraction to him. He had stirred something in her, but she pushed the feelings aside and focused on the reason she was there: to get information about her fiancé.

Flemmi delivered a gut punch. “He’s got himself involved with a high-priced call girl that’s been bleeding him to death,” Flemmi told her. “Boy, she must have something special because he’s borrowed a lot of money from me. Sorry, Shirley—no reflection on you, but it’s been a big joke around here.”

Grispi felt furious and embarrassed all at once. “I guess I’m just too trusting, or maybe stupid would be a better word,” she said, trying to hold back her tears because she didn’t want to cry in front of him—though they came streaming down her face anyway. Sliding out of the booth, she didn’t make it far before Flemmi grabbed her, pulled her in close, and kissed her passionately. Shocked at what she’d learned and reeling from the unexpected kiss, she pulled away and hurried outside the bar, where she broke down sobbing.

The very next day, Grispi ended her engagement, and soon after, the former couple put the gas station up for sale. She took a job bartending at an old dive called the Quincy Lounge. One night, she heard that deep voice again and looked up to see Flemmi standing in front of her. She was instantly overcome with desire. He asked her out to dinner. She said yes.

That night, before heading to a restaurant, he told her he needed to stop by his office, which was located across the street from his bar. Grispi descended a flight of stairs that led to his office, where she found a couch, a desk with multiple phones on it, and a taxidermized shark hanging on the wall above it. Flemmi pushed a button on the wall, and two doors slid open, revealing a bar. He poured Grispi a drink. “You must like sharks,” she said. “Did you catch that one hanging on the wall?”

A look of surprise came over his face, and then Flemmi smirked. “You really don’t know what that shark signifies?” he asked.

It was true; she didn’t. Grispi was naive. She was also a virgin. She had been saving herself for her fiancé, but she was wildly attracted to Flemmi, and when he pulled her onto the couch in his office that night, she was done saving herself.

A couple of days later, Grispi and her girlfriends were in an hours-long line waiting to get into a new nightclub that had just opened beneath the Neponset Bridge in Quincy when she felt someone tap her on the shoulder. “Come with me, ladies,” the man said, ushering her and her friends into the club and seating them at a table right in front of the band. It turned out that Flemmi had seen her and gotten them in through his connections with the club owner. Throughout the night, waiters catered to her and her friends, refusing to let them pay their tab. Grispi felt like a celebrity. And she liked it.

That’s what it was like to be with Flemmi. He doted on Grispi and made her feel special, and people treated him like he was somebody. He squired her to trendy restaurants and nightclubs throughout Boston and the North Shore. It wasn’t long, though, before Grispi saw another side of her new boyfriend.

During the early years of Flemmi’s reign of terror, he dated Shirley Grispi who was able to piece together how one of his notorious murders intersected with their time together when she read Carr’s book. / Photo by Michael Adno

Flemmi and Grispi were always going somewhere together. Yet not everything always went according to plan. One night, on their way out on a date, Flemmi pulled the car up in front of the Dudley Lounge and told Grispi he’d be right back. He needed to go inside to take care of some business. While she waited in the car, three intoxicated men came down the street and knocked on the door.

“Open the window,” one of them said, laughing. “We want to see your pretty face.”

They continued harassing her. Grispi ignored them until—slam!—one of them was splayed across the car windshield. An enraged Flemmi had emerged from the bar and was beating all three of them, landing punch after punch. Grispi watched in horror as blood shot out of their faces, splattering across the front windshield. Even from inside the car, Grispi could hear bones cracking and men screaming as Flemmi wailed on them while they begged him to stop.

Afterward, Flemmi—winded from the effort and covered in blood—scrambled inside the car and sped away, shouting at Grispi to look back and see if there were any witnesses. Grispi was shocked, having a hard time believing that one man had just beaten three drunks within inches of their lives for no apparent reason. They drove in silence to Wollaston Beach in Quincy.

When they arrived, Flemmi swung the car into a parking spot facing the ocean along the sea wall and slammed the gear into park. Grispi stepped outside and climbed up onto the sea wall. Before she knew it, she felt a blow to the head that sent her flying over the wall onto the sand. She was out cold. When she came to, she found herself looking right into Flemmi’s eyes. He was holding her in his arms. “It’s your own fault,” he told her. “You shouldn’t have been flirting.”

“Flirting? You asshole,” she told him, crying. “I wasn’t flirting. I was trying to ignore those guys. And don’t you ever put your hands on me like that again. Do you understand?” As she struggled to wrestle out of his grip, he tenderly wiped the tears from her bruised and swollen face.

That night marked the first time Flemmi hit her, but it wouldn’t be the last. Soon, a familiar pattern emerged. Flemmi would lose his temper, usually after becoming jealous for some reason, and beat Grispi. Then he would buy her gifts such as diamonds, a car, or expensive clothing and beg for forgiveness until they tumbled back into bed together and passionately made up. Until, that is, the next time.

For a while, Grispi thought Flemmi’s jealous fits of rage were a result of how much he loved her. Yet after a while, she came to believe it was the violence itself that Flemmi loved.

For a while, Grispi thought Flemmi’s jealous fits of rage were a result of how much he loved her. Yet after a while, she came to believe it was the violence itself that Flemmi loved. She noticed how many fights he got into and how he often talked in graphic detail about the men he killed while fighting in the Korean War—often by shooting them and then bludgeoning them to death with the butt of his rifle.

After one attack, Grispi told Flemmi she wanted to leave him. He put a gun to her head. Another time, Flemmi had beaten Grispi’s face, and when he went out to get bandages from a nearby drug store, she escaped and raced to the police station. There, she asked to speak to the captain, who was a family friend. She told the captain what happened, but instead of protecting her, he immediately called Flemmi.

The captain drove her to the hospital, where he told the doctors she had been in a car accident, and they diagnosed her with a fractured skull. A week later, she was ready to go home, but she knew she would never be safe in Boston. So she packed her bags and moved to Miami with a friend to start her life over. Soon enough, though, Flemmi found a way to get in touch with her, and as soon as Grispi heard his voice, all desire she had to stay away from him vanished. She gave Flemmi her new address and he flew south to see her. They spent a few whirlwind days together in Miami out on the town, and she agreed to move back to Boston to be with him. (When contacted about an interview with Flemmi, Michael Natola, the gangster’s most recent attorney, said he had no way to contact his former client and did not know where he is incarcerated. Flemmi is serving a life sentence at an undisclosed federal prison; in 2021, his attempt at compassionate release was denied.)

Not everyone understood Grispi and Flemmi’s relationship. Even one of Flemmi’s own associates, the notorious gangster Edward “Wimpy” Bennett, often asked Grispi what she was doing with Flemmi. He warned her to get away from him, saying that he was bad news. Her first impression of Wimpy was that he looked like an older, distinguished gentleman who was classy. But there were times when Flemmi wasn’t around that Wimpy would tell her to ditch him, touching her hand in a seductive way that made her feel scared of him, too.

When Grispi returned to Boston from Florida, Wimpy brought her and Flemmi to Walter’s Lounge—operated by Wimpy’s brother, Walter Bennett, who ran a loansharking and betting racket—to talk about their rekindled romance. Seated with them in a booth, Wimpy said, “You know, Stevie, you two are not good together, and I doubt it’ll change, and it’s going to affect business,” adding that what Flemmi did to Grispi could not happen again. When Flemmi was mad, he would clench his jaw muscles, and she noticed that while Wimpy spoke to him, they were pulsating a mile a minute. But when he opened his mouth to speak, he just told Wimpy he was sorry and assured him it wouldn’t happen again. Flemmi had previously told Grispi that Wimpy was his partner, but his behavior around him convinced her that Wimpy was, in reality, Flemmi’s boss.

Grispi met other gangsters during her time with Flemmi, including Walter Bennett. She became close with his mistress, with whom he had children. She also met “Cadillac” Frank Salemme, who she remembers as a quiet gentleman who never said a vulgar word. When Grispi and Flemmi were going out, he often made stops for business, and those included visits to Walter’s Lounge, where they would have a drink with Salemme. She observed how Flemmi and Salemme always got out of the car to converse. They never talked in their cars because they knew the FBI had them bugged. She also spent time with Flemmi’s brother, Vincent “Jimmy the Bear” Flemmi, who also once hit on Grispi. She knew to never say a word about it.

Seeing the guns, violence, and shady friends made it obvious to Grispi that her boyfriend wasn’t just someone who owned a bar and occasionally lent people money. He was a criminal—or, as she referred to him, a wise guy—even if, she says, she never knew the true extent of his crimes. Though Grispi understood much more than she did at the beginning of the relationship, she continued to feign naiveté, keeping her mouth shut and never asking Flemmi any questions. She now believes it’s what kept her alive.

Still, spending time around all of these characters began to change Grispi. When her brother-in-law crassly came onto her, she told Flemmi. Flemmi went to the Canton bar that her brother-in-law owned, reached over the bar, grabbed him by the neck, lifted him off the floor, and heaved him across the room. Then Flemmi beat him mercilessly until the man was nearly unconscious. When Flemmi stopped, he shouted, “You ever go near her again, I’ll kill you.”

Grispi was disgusted with herself for setting the attack into motion and for feeling little to no remorse. She was becoming like them, and it seemed like there was nothing she could do about it.

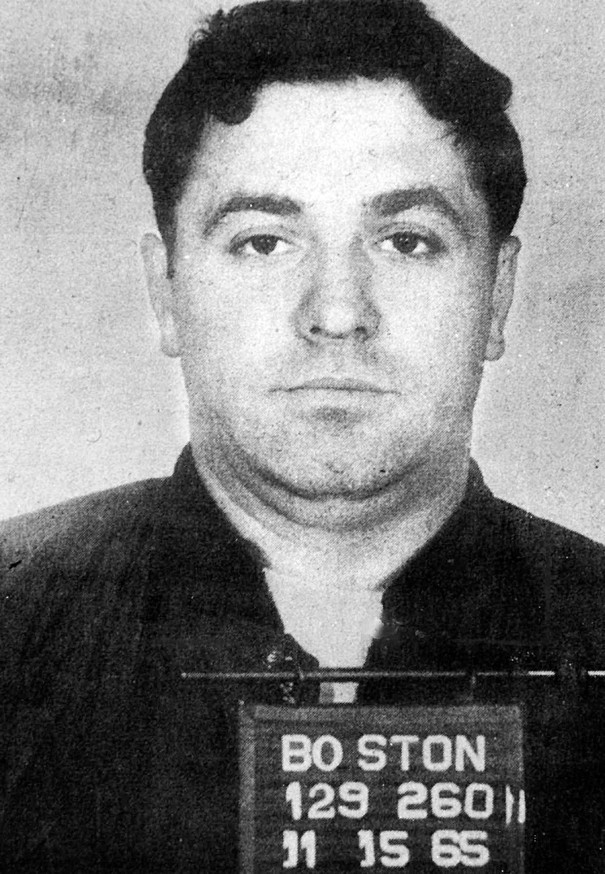

Flemmi pictured in a mug shot earlier in his career. / Wikimedia Commons/Federal Buraeu of Prisons

As jealous as Flemmi was of any man who so much as looked at Grispi, he was hardly faithful to her. One day, she received an envelope in the mail and opened it to see a note that read, “Stevie Flemmi’s Wives and Illegitimate Children” staring back at her in bold print. Beneath that was a list of four women’s names and addresses. Grispi called a friend, and together, they went to an address listed under the name Marion Hussey. They walked up the front stairs of the Dorchester triple-decker and rang the bell. After being buzzed in, they looked up at the top of the staircase to see a tall, attractive brunette looking down at them. “Come up, Shirley,” she said. “I’ve been expecting you.”

When Grispi asked Hussey how she knew Grispi’s name, Hussey told her that she must have gotten the same letter as Grispi. “Are you his wife?” Grispi asked. Hussey replied no. Then Hussey explained the reason they weren’t married was because he was already married to someone else, with whom he had two daughters. Grispi learned that Hussey also had a young son, Billy, with Flemmi, as well as a daughter from another marriage.

Reeling, Grispi left the house and tracked down Flemmi, upset about what she had learned. Flemmi told her the only reason he was with Hussey was because of his son and that his wife refused to divorce him.

Grispi was hurt and furious, and she thought back to the time, a few years prior, when she had discovered she was pregnant. When she told Flemmi, he told her that she would be getting an abortion. His attitude toward the situation stung her badly. Why would someone who supposedly loved her not want a part of her? At the time, she had no idea that Flemmi had children with other women. That would’ve only stung worse.

Though Grispi wanted a child, she realized she’d be raising it alone if she didn’t have an abortion, so she told Flemmi to arrange the procedure. Flemmi drove her over the Charlestown Bridge and pulled up in front of a rundown house in a rough neighborhood. He told her there was a doctor inside who would be taking care of the pregnancy. It was the 1960s, and abortions were illegal.

“You’ve got to be kidding,” she said, looking at the house.

Ignoring her, he opened the car door and said, “Shirley, it’s this or nothing.”

“You’ll be fine,” he added. “We’ll be in and out of here in less than an hour.”

Terrified and torn over ending her pregnancy, Grispi’s disdain for Flemmi in that moment made her decision an easy one. She wanted the pregnancy over with and wanted Flemmi out of her life. She entered the dingy apartment and was met by a nurse. “I’ll be waiting in the other room,” she recalls Flemmi saying. Turning to the nurse, he added, “Take care of my little girl.”

After an agonizing procedure, Grispi was convalescing in the home of Walter Bennett’s girlfriend when she developed a severe infection. Flemmi refused to take her to the hospital; instead, he took her to another back-alley doctor, who immediately sent her to the hospital, where she stayed for several days being treated for an infection that could have killed her.

A few years later, Grispi became pregnant again and lost the baby in a miscarriage, though she never told Flemmi. Later in life, she tried but was unable to have children, and her doctor told her there was so much scarring in her uterus that she would have to get a hysterectomy. Meanwhile, Flemmi went on to have two more children with Hussey.

Grispi’s resentment toward Flemmi over the abortion and the loss of her second pregnancy simmered for years, as did her desire to leave him. It felt almost impossible to do—until the law got involved.

One day in 1969, Grispi received a call from Flemmi’s brother, Vincent “Jimmy the Bear” Flemmi. He told her that Flemmi, Salemme, and fellow gangster Peter Poulos had fled the state after being tipped off that they were all about to be indicted. Jimmy the Bear instructed Grispi to go to a particular pay phone on the street and wait there. She did as she was told. When it rang, she picked it up and heard Flemmi’s familiar voice on the other end of the line. “Get out of Boston,” he told her. “Go to your mother’s cottage in Middleboro. Make sure no one follows you.”

“Why, Stevie? That place is in the boonies,” she said, the gravity of the situation not yet sinking in. “I hate going there.”

“Please, Shirley, for once, don’t give me any flack,” he shouted. “I’ll call you there in a few days. Stay put.”

As usual, she obeyed, hiding out in Middleboro until he called and told her to go to the Providence airport. Though Grispi had wanted to get out of her relationship with Flemmi, he always had a way to pull her back in. She could see he was at a low point, and despite all the abuse, she felt a nagging obligation to stand by him. When he asked her to get on a flight to meet him where he was hiding out in L.A., she said she would do it.

When Grispi landed in L.A., Flemmi told her they would be leaving the next morning to drive East, but he had a last-minute detail to tie up before they left. She didn’t ask any questions. The next day, they drove to Las Vegas and checked into a small motel just off the strip. After bringing their bags inside, Flemmi took the car keys and said he would be right back. He returned a few hours later, disheveled and exhausted.

Following a day of gambling, Flemmi and Grispi drove north through the Rocky Mountains to Wyoming and then to New York, where Flemmi sent her back to Boston. After that trip, she moved to Taunton to get away from Boston and kept a low profile. She worked as a secretary in a dentist’s office and tended bar at night. She visited Flemmi in New York, traveled with him to Florida for a few weeks, and then spent time with him in Montreal, where he hid for four years.

During the early months of Flemmi’s time on the run, he called Grispi often, telling her he wanted to marry her someday.

But the distance between them was what Grispi finally needed to free herself from Flemmi. They began drifting apart, and in 1972, she met the man who would become her husband. By that time, she hadn’t spoken to Flemmi in a while but knew she had to tell him. If he found out about her new relationship before she said anything, there would be a price to pay. So she summoned the courage to call him in Montreal.

“I can’t see you anymore. I’ve met somebody, and I want to be with him,” she told Flemmi.

He grew quiet.

“You deserve to be happy,” Flemmi said. “And I don’t think I can ever come back anyway. You’ve always stuck by me, even in bad times. And you’ve never done anything to hurt me.”

Flemmi leaves a Boston courthouse in 1974. When witnesses recanted their testimonies, prosecutors dropped the criminal charges against him, leaving Flemmi free to continue his life as a gangster. / Photo by Joseph Runci/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

But Flemmi did come back. After key witnesses in the case recanted, prosecutors dropped the charges, and Flemmi returned to Boston in 1974 a free man. He continued his reign of terror, joining forces with Bulger to create the deadliest crime syndicate in the city’s history.

Grispi only saw Flemmi a few more times in her life—once at the wake of a mutual friend, where Flemmi pestered her to see him again, and once when she and her husband were living in Plymouth. She was out for coffee with her sister one morning near Buzzards Bay when she looked up and saw Flemmi ominously sitting at the counter. Terrified, she tried to ignore him. When she got in her car to leave, he followed her. She tried to lose him, but he kept up the chase.

Shaking like a leaf, Grispi eventually pulled over on a busy road to confront him once and for all. She told Flemmi she was married now, and she never wanted to see him again. Then she got back in her car and drove off.

Soon after that encounter, Flemmi moved to Plymouth and became her neighbor. He was arrested in 1994 and locked up in the Plymouth County Jail, just a few miles from where she had moved in Onset. The FBI questioned Grispi several times and asked her about Peter Poulos and the Bennett brothers. They told her they couldn’t understand why she was still alive or how she had survived Flemmi.

Flemmi never left prison after his arrest, but it would be years before he was convicted of murdering 10 victims, including some people Grispi knew as his associates, such as Wimpy and Walter Bennett. He was also convicted of luring Hussey’s daughter, Deborah, to a house where Bulger then murdered her. Flemmi ripped her teeth out so she couldn’t be identified. During Whitey Bulger’s criminal trial, it came out in the proceedings that Deborah, who called Flemmi “Daddy,” had been sexually abused by him as a child before going on to be his lover when she was older. She was the older half sister to his biological children.

She wasn’t the only lover Flemmi killed. In 1981, after Bulger found out that Flemmi had told his longtime girlfriend Debra Davis that they were FBI informants, Bulger said she knew too much and must die. Flemmi lured her to a house where Bulger strangled her. Afterward, Flemmi ripped her teeth out, too.

Notorious Boston gangster Stephen Flemmi pictured on the back cover of Rifleman, a book about his life and crimes by journalist Howie Carr. / Photo by Michael Adno

The same year that these details emerged during Bulger’s criminal trial in 2013, Grispi was on her couch in West Palm Beach, Florida, reading a copy of Rifleman, Howie Carr’s book about Flemmi, which published Flemmi’s 2003 confession to the feds. When Grispi came across the section about the murder of Poulos, who had been on the lam with Flemmi in L.A., her blood went cold.

In his confession, Flemmi didn’t mention that he and Grispi had driven from L.A. to Las Vegas together. Instead, he said that he had taken that drive with Poulos, killing him on the way and leaving his body in the Nevada desert.

Suddenly, memories of her trip came rushing back to Grispi and she sat up, letting out a gasp of recognition. It all made sense: The night Flemmi ran out in L.A. to take care of business; Flemmi leaving the hotel in Vegas and coming back sweaty and disheveled. He must have killed Poulos that night, put him in the trunk of the car—with Grispi in the passenger seat—and drove the body all the way to Vegas, where he ran out that night to bury Poulos’s bullet-ridden body in the desert, she thought. Flemmi must have lied in his confession—and he left her out of it entirely.

Grispi felt like throwing up. Who was this man she was in love with? She closed her eyes and thought about Deborah Hussey and Debra Davis and all the other people who were buried 6 feet under. And all she could do was thank God that she had gotten away.

First published in the print edition of the April 2024 issue with the headline, “Confessions of a Boston Moll.”