Will the ‘red wall’ reshape British politics again?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

A pink dawn rises above the low-slung warehouses of Grimsby’s docklands while men in white coats and wellies call out prices for pallets of fish on ice.

The fish are not caught locally but are instead mostly imported from Iceland. It is a far cry from the 1960s, when Grimsby was the biggest fishing port in the world with 570 trawlers.

Now there are just a dozen fishing boats catching crabs, although thousands of locals work in the fish processing industry turning out battered fillets, fishcakes or fish fingers.

The loss of that fishing fleet — blamed on the historic “cod wars” with Iceland and EU membership — was brandished by the Leave campaign in the run-up to the referendum, when the town voted overwhelmingly for Brexit.

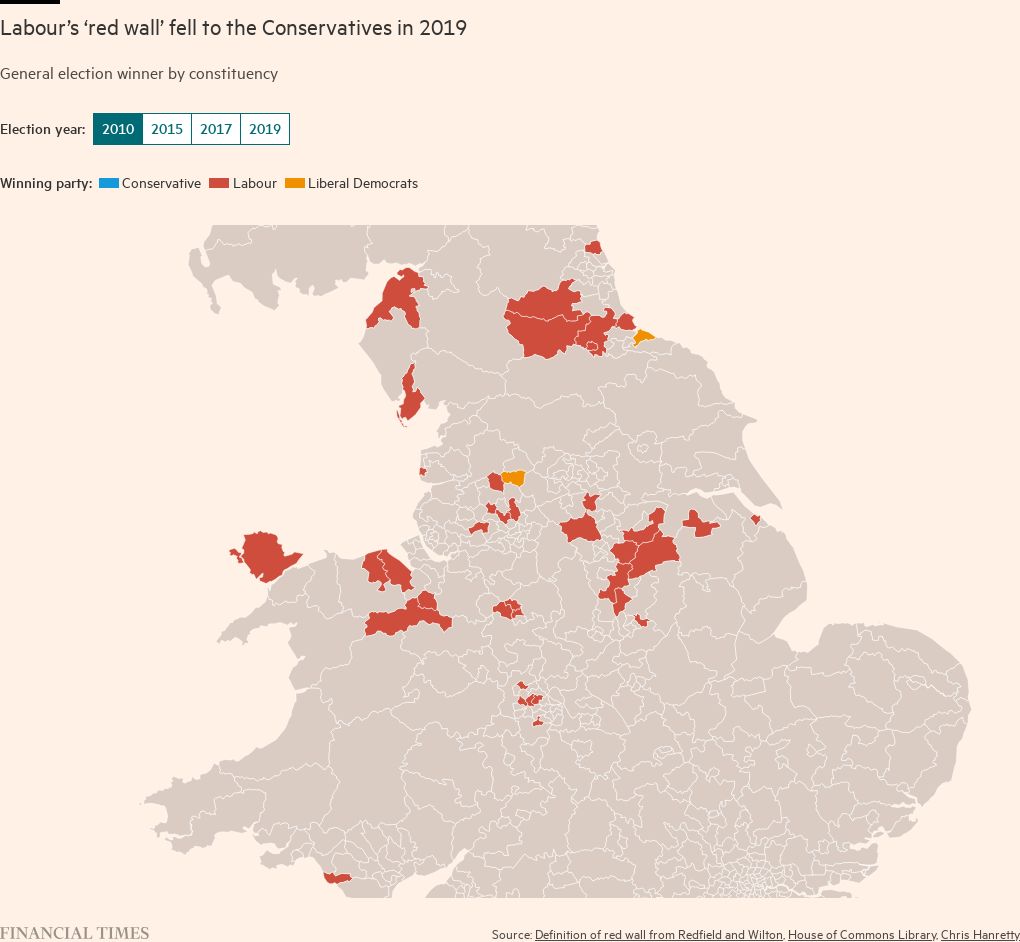

In 2019, eager to see Brexit become reality, voters were won over by Boris Johnson’s promise to get the job done. The Conservatives went on to seize from Labour a series of largely working class post-industrial seats across northern England, the Midlands and north Wales — the so-called red wall — in a seismic shock to Britain’s political norms.

It was in this market, days before the vote, that Johnson posed in a white hat while clutching a dead-eyed cod, surrounded by grinning fish traders. Lia Nici, who in 2019 became Great Grimsby’s first Conservative MP in 75 years, recalls the former prime minister being treated like a “rock star” on that cold December morning.

But fast forward more than four years and the Conservatives, having ejected Johnson as leader in 2022, are struggling to cling on not only to Grimsby but many of the other 50 or so red wall seats.

Kurt Christensen, a former fishing entrepreneur who went on to offer services to the offshore wind industry, says Johnson was “passionate about Grimsby” unlike most other London politicians. “He went to the fish market and held the audience in the palm of his hand. He was a good man, the only person who could get Brexit done,” he adds.

He is unimpressed by Rishi Sunak, the current Tory leader, who he describes as “incredibly weak”. “He doesn’t come across as a real leader,” says Chistensen, mixing tomato ketchup into his baked beans at the Kingsway Hotel in seaside town Cleethorpes, which overlooks the Humber estuary where distant wind turbines are visible on a clear day. “You can see if you met him and shook his hand it would be . . . slimy.”

It is here, in seats like this, that the realignment set to hit British politics is most apparent. A resurgent Labour party is leading the Tories in red wall areas by more than 20 points — roughly in line with national polls — according to research by Redfield and Wilton, a polling firm.

Three main factors led to the collapse of the red wall in 2019: anger that parliament was blocking Brexit, dislike of Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, and enthusiasm for Johnson. The fact that all three issues are now moot bodes ill for the Tory party.

Philip van Scheltinga, director of research at Redfield, argues that in a post-Brexit world there is little binding red wall voters to the Conservatives.

“The Conservatives breaking through in those seats in 2019 was a unique opportunity that perhaps only existed at that moment in time,” he says. “You had a broad coalition of voters from across the country who otherwise do not have much in common . . . all voting Conservative. Once Brexit was done the Conservatives were rudderless.”

But there seems to be little love among locals in Grimsby for Sir Keir Starmer, whose route to ending the Labour party’s 14 years in the political wilderness also goes through the red wall.

Support is also growing for emerging political players such as right-wing populists Reform UK, backed by Nigel Farage, which offer an alternative to Labour and could take votes from the Tories.

Whoever wants to take control of the red wall needs to understand what voters there want now, locals say, and not take their support as a given.

For many outsiders, the economic story of Grimsby is about the rise and fall of its fishing fleet, which has left parts of the town struggling with crime, drugs, low skills and boarded-up shops.

While poverty is undeniably an issue here, the reality is more nuanced. The false narrative about Grimsby is that “we are pathetic, needy people and we supported Brexit so perhaps we are a bit thick”, says the MP Nici. “But people went into Brexit with their eyes open. That vote was about a sense of place, about the culture of a country.”

The town has opened a new chapter as a centre for the offshore renewables industry, a rapidly growing employer. Many of the boats in the harbour provide operation and maintenance for offshore wind.

Christensen, whose company Wind Power Support offered port services to this new wave of companies, says: “I’m fiercely proud of my town. Grimsby has been in a bad place but it’s going to be in a good place.”

Other entrepreneurs who see Grimsby’s potential include Tom Shutes, a property developer who took over the derelict Ice Factory, an iconic red brick building which once supplied ice for the fishing industry.

Walking carefully over rotten timbers, amid hulks of rusted metal, he outlines his plan for an exhibition centre and adjacent hotel. “The idea is to showcase the very best of the renewables and green maritime industries,” he says.

Nearby is the Black Gull café run by Sam Delaney, a former City trader who nearly lost his life to addiction and now offers creative sessions for people who have struggled with substance abuse. “When we took the building from [the landowner] the windows were rotten, there were dead pigeons, bird crap, it was a shell,” he says.

“Grimsby is a town that’s in recovery, just like I was,” he adds. “When I went into recovery I thought it would just get better and better, but it’s not like that, recovery is up and down.”

When Nici was elected in 2019, she says there was a strong feeling that Labour had taken the town’s support for granted.

Residents expressed their frustration at the ballot box — first with the Brexit vote, and then by taking a chance on the Conservatives’ vision for the area.

“There were seats with majorities of 20,000 which had been taken for granted by Labour for decades, but in 2019 people were prepared to listen,” says Guto Harri, former director of communications in Johnson’s Downing Street.

“Boris went to those places and said ‘I care for you’. That’s the trick that he pulled off, voters like to feel like someone cares for them and they aren’t being neglected . . . for once they thought there was no reason they shouldn’t vote Tory.”

Nici is keen to point out that Grimsby has been designated as part of a new “Humber Freeport” and has received government funding worth more than £100mn through the government’s flagship “levelling up” programme.

But Labour says the levelling up funds do not compensate for 14 years of deep cuts to the annual grants given by central government to local councils.

The Conservatives’ record on levelling up is likely to be one of the metrics by which it is judged by voters across the red wall at the next election. Johnson’s pledge to lift struggling areas of the country was knocked sideways by the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which together soaked up hundreds of billions of pounds of taxpayer money.

Last week a report from the UK parliament’s committee of public accounts found that just 10 per cent of the money intended to regenerate local areas under the government’s levelling up programme had been spent so far.

John Stevenson, the Carlisle MP since 2010 who chairs the Northern Research Group of Tory MPs, notes that June will mark the 10-year anniversary of former chancellor George Osborne launching the “Northern Powerhouse” — a forerunner to the wider concept of “levelling up”.

Stevenson describes the success of levelling up as “half and half”. “It put the north on the agenda and you’ve seen some substantial changes in terms of devolution, which is the very significant passing down of powers to northern mayors . . . [but] it’s a work in progress.”

One of the major criticisms of the government’s commitment to the north and Midlands is Sunak’s decision in October 2023 to scrap the northern leg of the HS2 rail line. The move met fierce opposition from Tory MPs in the north-west.

Stevenson, whose own seat could be vulnerable, accepts that the upcoming general election will be “very challenging” for his party.

Unless the polls are wildly wrong, Britain is heading for a major political reset, with Labour making substantial gains — and reversing most of its losses from 2019.

Luke Tryl, director of the More in Common think-tank, says that the Conservatives “overestimated the realignment” that took place in the red wall last time around. Many of the voters who switched sides were “never economic Conservatives”, he adds.

“Sometimes there’s a mis-assumption [the red wall represents] the poorest seats, whereas actually there’s a reasonably high level of home ownership compared to inner cities. But there’s no doubt voters there feel the [pressures of the] cost of living,” he says.

As a result, the traditional Tory offer on the economy has not been “particularly appealing”. A survey by his think-tank, conducted in the days after the spring Budget, found the government received “zero poll bounce” from the fiscal statement and its national insurance cut.

Despondent Tory MPs do not like to admit on record that they have given up the fight. But one red wall parliamentarian, speaking on condition of anonymity, says the prospect of holding their own seat is now “hopeless”. Instead, they are thinking about their next job beyond politics.

Musing on the mood among colleagues, the MP adds: “There’s depression. People are a bit lost — trying to cajole themselves to stay motivated. But older party activists say it’s worse than the run-up to [Labour’s landslide in] 1997. There’s not the same level of fight, that sense of ‘let’s go to war’, there was then.”

Another Tory insider agrees that morale among red wall MPs has worsened since last summer. “We’ve pulled all the levers that were available six months ago — reshuffle, party conference, budget. Nothing has moved the opinion polls.”

Conservative officials say that while there was a private consensus among MPs last year that a 10,000-vote majority was the threshold above which a seat was considered “safe” at the next election, that threshold is now considered to be a 16,000 majority. For context, almost all of the red wall seats hover near or fall far below that figure.

One former minister warns that the party’s electoral strategy is mired in “confusion”, adding: “It’s unclear whether we are trying to rebuild the 2019 red wall coalition or whether we’re trying to strengthen the blue wall [seats in the south where the Tories are threatened by the Liberal Democrats] or a mixture of the two.”

The Tory MP says Conservative headquarters’ strategy to protect its 80 most marginal seats and gain 20 extra constituencies is predicated on saving a high proportion of seats in the north that “are already written off by most MPs and strategists”.

Some MPs are now urging a “core vote” strategy in which the party pivots to saving its traditional heartlands in the shires and home counties across the south of England, jettisoning the red wall.

Now the Conservatives’ own attack line about taking voters for granted is being mounted against the party itself by populist insurgents in Reform UK, led by Richard Tice.

In March former deputy Tory chair Lee Anderson, the MP for Ashfield — a constituency in Grimsby’s neighbouring county — announced his defection to Reform, declaring “I want my country back”.

Reform insiders claim up to 10 other Tories could follow suit, an assertion dismissed by Conservative officials. Nonetheless, Reform is polling at 11.3 per cent nationally, and is said by its campaigners to be gaining particular momentum in the north and Midlands.

The party’s radical stance on immigration — it advocates “net zero” regular migration, for example — has gained currency in the red wall.

Tory strategists are concerned about Reform sweeping up voters who would otherwise back the Conservatives, helping a swath of seats fall to Labour.

In Grimsby, many local residents expect former Labour MP Melanie Onn to sweep back in, despite a lack of enthusiasm for either of the two main party leaders. Gordon Gregory, a retired fisherman, describes Starmer as “weak” and “vague”, but adds: “I’ll bet you £1,000 Labour win, it’s 100 per cent nailed on.”

Labour’s candidate Onn, who lost by 7,331 votes in 2019, found the defeat “really brutal” and is only cautiously optimistic about her chances this time around, pointing to “fatigue” and “apathy” towards both main parties.

“The result in 2019 was a result of people being frustrated by the political status quo, the fact that Brexit wasn’t happening. It was a two fingers up to the Big Man,” she says.

Now residents, known as Grimbarians, appear more responsive to Labour’s message, according to Onn, who says the town needs the “right tools and leadership”.

One Must-Read

This article was featured in the One Must-Read newsletter, where we recommend one remarkable story each weekday. Sign up for the newsletter here

Onn, who until last year was deputy chief executive of trade body Renewables UK, says she is proud of the town’s potential for low-carbon energy. The challenge, she adds, “is to convince people there are enough skilled jobs” in the sector. “Then people will see how much opportunity and prosperity there is here.”

Even if Labour wins back most of the seats it lost in 2019, recent history shows the party cannot rest on its laurels. Although Grimsby was in Labour hands for nearly eight decades, the majorities were often small. In 2010, it was 714.

But Martyn Boyers, chief executive of Grimsby Fish Market, believes the Conservatives’ days in the town are numbered now that Brexit is no longer top of mind for voters. “[The year] 2019 was an exceptional moment,” he says.

Nici, the Great Grimsby MP, concedes she is facing a tough fight. But she believes a message of investment and optimism offers the best chance to extend her party’s longevity in the red wall. “Whether people like or dislike Boris, what he did for people in areas like Grimsby was to give them belief that their . . . towns were worth investing in,” she says. “It has given them aspirations.”

Data visualisation by Jonathan Vincent

Comments