So, no, there probably isn’t room in MLB for teams to perform dance routines at home plate during games.

And the NFL probably would take a hard pass on having its players run into the stands between quarters to greet fans.

The chances of the NBA instituting a rule requiring one player a game to shoot free throws while playing Dance Dance Revolution at the line are sadly slim.

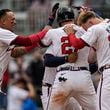

But, after watching an entertaining and energy-filled Savannah Bananas game at Coolray Field on Saturday afternoon – which included all of the above (one player took his turn at bat while following dance steps displayed on the stadium video board; he actually got a hit) – one was left with the question: Why can’t professional sports be more fun and fan-focused like this market-disrupting outfit?

The numbers would say that maybe they ought to consider it. Three games at Coolray Field (capacity: 10,427) this weekend sold out quickly, and the cheapest tickets available on StubHub for Sunday’s game as of Saturday afternoon were going for $158. When the baseball circus played at Houston’s Minute Maid Park earlier this month – their first-ever show at a major-league park – they sold out the 41,000-seat stadium in minutes, according to Bananas owner Jesse Cole. The ticket-lottery list is more than 2 million deep.

On Saturday morning, hundreds of fans were waiting at the gate 90 minutes before the noon first pitch, eager to take part in the spectacle (and to get the best seats, as seats are not assigned for Bananas games). Some had been there for more than two hours.

“I think it’s because of all the show,” said one of those fans, Michael Christman of Cumming, who had brought his family to the game and was among the first through the gates. “It’s a lot different than regular baseball.”

;The list of differences with regular baseball could fill a notebook. Banana ball principally is differentiated from the standard version by 11 rules, including a two-hour time limit, the batter is out if a fan catches his foul ball and if a player walks, he is free to advance past first if he can do so before every player on the field touches the ball. In the Bananas’ final at-bat, they invoked the Golden Batter rule, which allowed them to send a player to the plate out of order.

The game is meant to be played at a quickened, lively pace, and it rarely slowed Saturday, even with breaks for the home-plate umpire to twerk.

But there’s way more than the 11 rules that the Bananas use to stand out. Hot-dog plays – like catching fly balls behind the back – are encouraged. A reliever for the Bananas pitched while wearing a motorcycle helmet. There was something between innings called the Granny Panty Parade. The music (a lot of Taylor Swift) almost never stopped, even during at-bats and while the ball was in play.

“We solely focus on how do we create the best show every single night,” the yellow-tuxedoed Cole told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution between Saturday’s performances. “(Saturday night), we’ll do 15 new things we didn’t do in (the afternoon) game. Every single night is different.”

Much of what the Bananas do couldn’t be transported into a major-league environment. But they do two things (among many) that professional teams everywhere (including the Braves, Falcons, Hawks and Atlanta United) could do well to embrace further – to be more personal and more fun.

Bananas team members sign a lot of autographs and look for ways to connect with fans. They were there when the gates opened, and several of them stayed long after to accommodate fans’ autograph requests. One of them was former Georgia Tech pitcher Andy Archer, who did far more than sign his name while out on the stadium plaza. With a quiver and arrows slung over his shoulder (Archer – get it?), he engaged fans – “Is this your first game?” – and took photos, each time pretending to pull back a bow-and-arrow.

One boy walked away in delight, screaming “Archer!” over and over.

Before the game, as a member of the Party Animals (the Bananas’ standing opponent) walked behind home plate, he spotted a young boy in the stands holding a souvenir bat. He pantomimed a pitcher looking in for a sign, prompting the boy to take his stance. He pitched and then looked skyward after the boy swung – a home run.

“It’s been the most fun and meaningful thing I think I’ve ever done in my life,” Archer, who joined the Bananas for this season after working a hotel desk job for a year and a half, told the AJC.

What child doesn’t go to a game hoping for some sort of connection like that? Yes, in a stadium with 40,000 (or 70,000) fans, it’s a far different scale. And, yes, this is a very different product than major-league sports. These are shows, not games.

But why not mic up players and play it over the speakers (perhaps delayed), and encourage them to engage more with fans? Is it too much to ask them to commit to sign autographs before or after games? What if, before games, a player sat at a booth in the concourse and gave out free T-shirts to kids?

What about if players (or coaches) spoke directly to fans during the game, leading them in a cheer or encouraging them to get on their feet? Or addressed them afterward, thanking them for coming? There are athletes who connect with fans. But teams could easily do more.

“I just think the name of the game is we are able to sell out, we are able to draw these huge crowds, we’re able to impact people because we put fans first in a way that no one else in the country does,” Archer said.

As for the games themselves, they can always be sped up. Baseball did itself a huge service by instituting a pitch clock last season. What if the NBA allowed teams to take only one timeout in the final two minutes or tried the Elam Ending (which sets a target score – perhaps 25 more points more than the leading team’s score going into the fourth quarter – rather than use the standard time limit, eliminating the parade of game-extending fouls and free throws)?

The NFL presumably would outlaw the forward pass before unclenching one of its precious commercial breaks. But couldn’t the league mandate that replay reviews can take no longer than 45 seconds?

The protests aren’t hard to anticipate – the sanctity of the game must be protected; players have to focus on competition – but the response to that is to stop taking yourself so seriously.

Professional sports leagues are businesses, not ways of life. Athletes are performers. This is entertainment.

We now live in a world where the National League uses the designated hitter. The republic somehow has stood.

It’s not like MLB, the NBA or NFL is struggling. They probably don’t need to make the dramatic pivot to serve fans in the way that the Bananas do. But there’s likely an audience and a profit waiting for them if they do.

The Bananas will play six major-league stadiums this year. They could go international next year.

Asked if professional leagues or teams have sought his knowledge, Cole said that “we hear from people all the time. This industry, you share a lot of things and you try to help each other out.”

Those people, including those in Atlanta, would be wise to listen.

About the Author