In big cities, small towns and rolling Piedmont counties like Rappahannock, Culpeper and Fauquier, homes have become scarcer, costlier and more likely to be beyond the financial reach of many residents communities value and count on — teachers, health aides, elderly on fixed incomes and young adults.

Ordinary households are devoting an ever higher share of their income to securing shelter, often accepting longer commutes and structural shortcomings in exchange for an affordable mortgage or rent. And because the strains have become persistent, even in a time of active job creation, experts and policymakers are concluding that for now at least, the housing market is failing many working citizens.

“There’s a demand [for housing] that exceeds the supply across income levels,” said Patrick L. Mauney, executive director of the Rappahannock Rapidan Regional Commission, which studied housing in five Piedmont counties in 2022. He added: “When there’s a lack of supply, people end up paying more.”

Molly Brooks, who is leading Hero’s Bridge Village, a veterans’ affordable housing project in Warrenton, warned that “there is a senior housing crisis at our doorstep.” And at the extreme end, more elderly residents are facing homelessness for the first time.

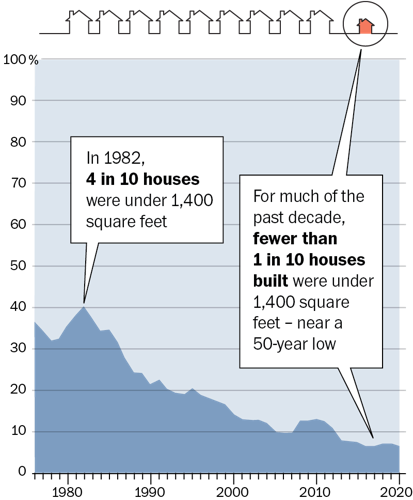

Families just stepping onto the housing escalator are another group that is especially pinched, partly because home builders increasingly build big. In 2020, builders across the United States completed only 65,000 entry-level homes (those up to 1,400 square feet) — less than one fifth of those completed in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

At Clevengers Corner, at the intersection of Rappahannock, Culpeper and Fauquier counties, a development called Stonehaven with more than 770 homes rises on former woodland. In February, there were four available homes for sale at well-beyond-affordable prices ranging from $619,690 to $820,290.

Virginia Realtors, representing 38,000 real estate agents in the state, issued a year-end report that underscores the problem: 98,464 Virginia homes sold across the state in 2023, a 20% drop from 2022, and the lowest sales total since 2014. Costly mortgages partly explain the falloff in home sales, but the main culprit was low inventory. Meanwhile, house prices rose briskly through the year, culminating with a median Virginia home price of $382,725 in December, about $24,000 higher than a year earlier.

Lower interest rates could stimulate more building soon, but at the end of 2023, the housing pipeline was anything but robust. From January through November last year, Virginia’s builders had obtained 32,871 building permits – 9.7% lower than the previous year.

Conservatives and progressives alike are troubled by the housing squeeze.

Virginia’s Republican Governor Glenn Youngkin warned that the state’s housing shortfall will undercut efforts to attract business and investment. Launching his “Make Virginia Home” campaign last year, he called for local governments to clear away layers of zoning and environmental regulations that stymie homebuilding.

This year he is summoning housing experts, policymakers and affordable housing advocates to a November conference in Virginia Beach to analyze the problem and explore ways the housing supply can once again keep pace with Virginia’s population, which jumped more than 10% since 2010 to 8.6 million.

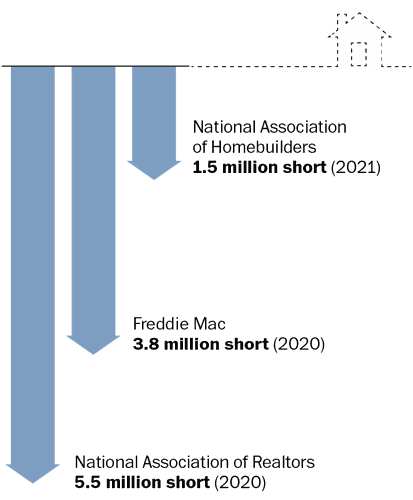

Similar warnings come from the generally progressive Brookings Institution. Jenny Schuetz, senior fellow at Brookings Metro and author of “Fixer-Upper: How to Repair America’s Broken Housing Systems,” told a congressional committee last September that “the U.S. has not built enough housing to keep pace with demand created by job and population growth, leading to historically lower vacancy rates and rapidly rising costs.” She added that “researchers estimate that the U.S. needs roughly 3.8 million additional homes nationally to address this gap.”

This is the first of a three-part series that examines the ways that what many are calling a national housing crisis is playing out in Rappahannock, Culpeper and Fauquier counties. The tight housing supply in the three counties tracks trends across much of the country. But because of their proximity to greater Washington, D.C., these counties face the additional pressure of in-migration from urban dwellers seeking an open landscape or just an escape from the dizzying real estate costs in the city and surrounding suburbs.

National housing squeeze hits home

By Tim Carrington and Laura A. Stanton — Foothills Forum

As a result of a nationwide shortage of housing to buy or rent in the past two decades, housing is more likely to be beyond the financial reach of many of the fellow Piedmont residents our communities value and count on – teachers, health aides, the elderly on fixed incomes and young adults.

Rural U.S. renters struggle to find affordable rent...

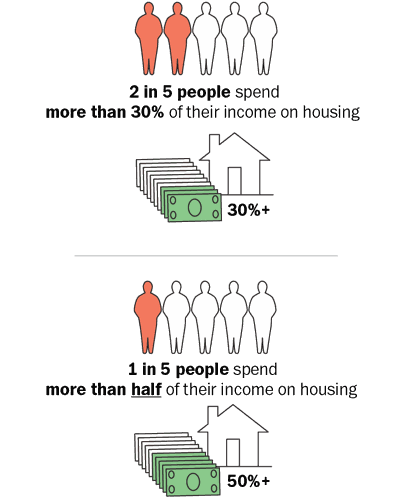

Among U.S. rural renters:

...buyers have fewer new small-home options...

Percentage of new U.S. homes below 1,400 square feet, as a share of new construction.

…and there is a deficit of housing inventory overall.

U.S. housing inventory falls short by millions, but estimates of vary on how many more houses are needed:

Who pays the price?

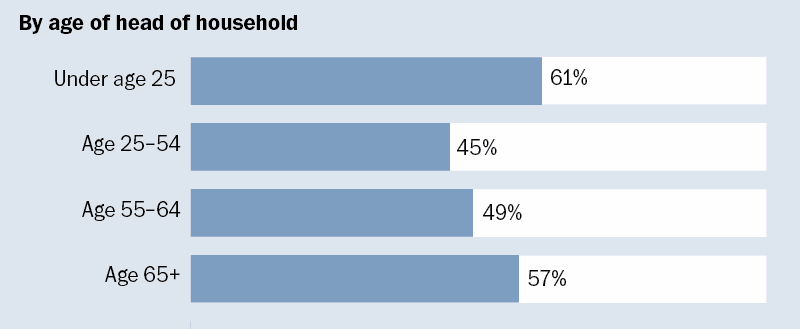

Percentage of renters considered cost-burdened in 2022:

More renters are paying a high share of their wages...

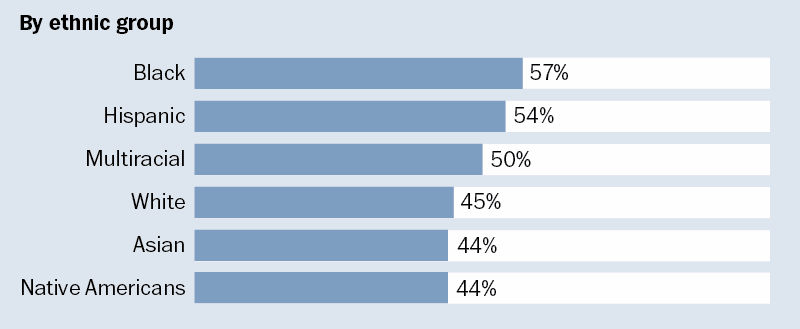

The number of renters paying more than 30% of income for housing roughly quadrupled in Culpeper and Fauquier counties, and nearly tripled in Rappahannock County.

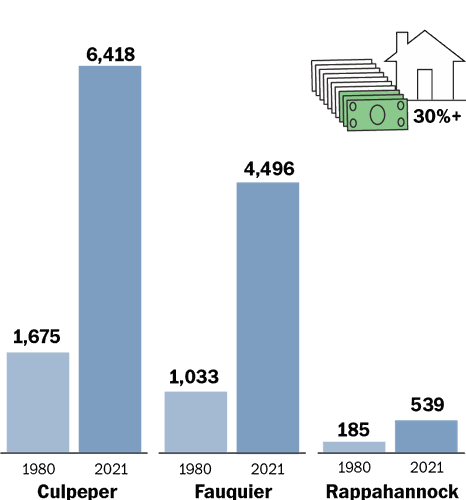

...more locals are finding themselves homeless...

Homeless count in Culpeper, Fauquier, Rappahannock, Orange and Madison counties, based on counts taken on the same night each year.

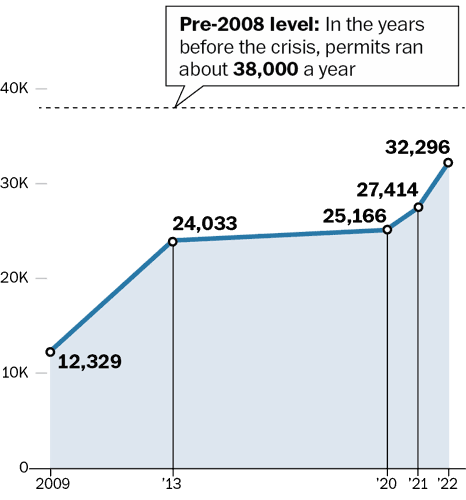

...and fewer new homes are being built

Housing permits in the greater Washington, D.C., area haven’t recovered to pre-2008 levels after the global financial crisis.

Sources: Harvard Center on Housing Studies; Housing Assistance Council; Foothills Housing Network; Steven Fuller Institute, George Mason University, U.S. Census Bureau

Remote-work arrangements and improved broadband access further encourage more high-paid workers to relocate to the rural Piedmont, at least part time. Those migrations drive up real estate prices, and the burden is mostly borne by local residents, particularly the elderly, the young, the under-employed and those stranded in low-paying jobs.

What’s affordable?

There is no price threshold above which homes become unaffordable. The key determinant of affordability is the relationship of housing costs to household income. Researchers, economists and local governments categorize households spending more than 30% of monthly income on housing as “cost-burdened.” The Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies found that among U.S. rural renters, 41% are over the “cost burdened” threshold. More worrisome, 2.1 million rural households, or 21% of renters, pay more than 50% of their income to rent a home. When housing costs reach this level, experts argue, families cut back on items such as dental care, car maintenance and healthy meals.

Habitat for Humanity in its 2023 State of Home Affordability in Virginia, puts the shortage of homes – for rent or purchase – at 110,009. The shortage has worsened by 47,033 since 2014.

Less resilient elderly residents may be suffering more. The Foothills Housing Network, which helps low-income residents in a five-county area avoid homelessness, last year worked with a 71-year-old Culpeper woman living in her car with a dog, as well as a married couple in their 50s, parking their live-in vehicle behind a Walmart.

Felicia Champion, program director at Community Touch, an organization that helps residents who are experiencing homelessness or are low income secure housing.

Felicia Champion, program director for Fauquier County-based Community Touch, a nonprofit that helps people avoid or move out of homelessness, said, “The homeless rate has increased drastically for the 60 and older population.”

Virginia typifies the mismatch afflicting much of the country: earnings aren’t keeping up with housing costs. According to Habitat for Humanity, a median-priced house in Virginia now requires an annual income of $75,412; meanwhile the median income in the state lags at $49,800. The upshot is that the American Dream of home ownership is mutating into the American Downsizing: outside the upper echelons, the same hard work and professional advancement is yielding homes that are smaller or less convenient than 20 years ago.

Elderly people who counted on Social Security to see them through have had to face a painful mismatch. Social Security said that in February 2023, the median monthly payment in the U.S. came to $1,781. In November, Zillow calculated the typical rent paid for a single-family home to be $2,148, with the less expensive option in a multi-family building being $1,845 – both larger than the median monthly Social Security payment.

The number of households considered cost-burdened has grown in all three counties, according to the nonprofit Housing Assistance Council, which promotes affordable housing in rural America. In 1980, the group found, Culpeper had 1,033 residents spending more than 30% of their income on housing. In 2021, the ranks of Culpeper’s cost-burdened households had swelled to 4,496. In Fauquier, there were 6,418 cost-burdened households in 2021, up from 1,675 in 1980. In Rappahannock, there were 539 households spending more than 30% of their income on housing in 2021, up from 185 in 1980. According to Zillow Research, part of the sprawling real estate information platform, “communities where people spend more than 32% percent of their income on rent can expect a more rapid increase in homelessness.”

The century’s two traumas

A big part of the housing crunch can be traced to the 21st Century’s two economic traumas – the global financial crisis in 2008 and 2009, and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021.

The financial crisis punctured a bubble in housing prices, which had surged as homebuyers borrowed massively while the banks conjured up financial instruments to spread the risk. The highly leveraged financial structures cracked, hobbling financial institutions and putting families at risk of evictions and foreclosures. Mergers and government rescues helped financial institutions escape a full meltdown.

When the crisis subsided, wary homebuilders erected fewer houses. Until the collapse, according to the Stephen Fuller Institute at George Mason University, housing permits in the greater Washington metro area were running at about 38,000 a year. By 2009, permits had plunged to 12,329. New home starts never regained the earlier levels, edging up to 24,000 in 2013 and running at about 25,000 through 2020.

With fewer new homes going up in Washington, D.C., and its surrounding suburbs, existing homes became more costly, which in turn sent some homeowners to the Piedmont in search of comparatively less expensive dwellings. And that combined with interest from weekenders and retirees pushed up the costs for locals seeking to buy a home or secure an affordable rental.

Meanwhile, central bankers kept interest rates at historically low levels to assure needed liquidity in the world’s credit markets. The cheap credit encouraged investment, keeping wealthier homebuyers in the market and adding further upward pressure on home prices.

The second trauma – the COVID-19 pandemic – brought its own cascade of shocks and aftershocks. Lockdowns led to new patterns of remote work, with thousands of well-off urban professionals migrating from the largest cities to locations they found healthier and cheaper. But by migrating and buying, the transplants made real estate in their chosen settings costlier.

In Rappahannock, the demand for Airbnb rentals – catering to urban part-timers – took an estimated 15% of the rental properties out of the traditional rental market, shrinking an already small market and driving up the prices for what was left.

The next hit came in the pandemic’s aftermath, when supply chain snags created delays in parts and supplies, causing a surge in prices for everything from lumber to piping. Developers and construction firms also ran into labor shortages. Faced with too few workers, plus costly materials, builders held back, content to ride the higher prices on a smaller volume of houses. The result: the scarcity of dwellings worsened.

Analyzing the price shock, the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies calculates that nationwide between 2020 and 2023, housing prices jumped 37.5% and rents in professionally managed buildings rose by nearly 24% (without adjusting for inflation). At the low end of the homeowner market, the price of manufactured homes (mobile homes or trailers) surged during the pandemic. According to a report from the Housing Assistance Council, the average price of a new mobile home was $86,900 in April 2020. By April 2023, a would-be buyer could expect to pay $125,000.

Harder for renters

An available rental unit in a duplex in Culpeper. Recently, the two-bedroom unit was listed for rent for $1,500 a month.

In rural America, renters tend to be more financially stressed than those living in homes they own. According to the Housing Assistance Center, more than half the rural renters in the U.S. earn less than $35,000 a year; for homeowners, the figure is 25%.

Low vacancy rates in rentals are considered a sound predictor of financial stress, including rising homeless rates. According to Zillow, the vacancy rate last September stood at 6.4%, below the pre-pandemic – but already low – level of 7.1%. Because buying a home remains out of reach for many lower-income households, demand for rentals, and upward pressure on rents, will continue, Zillow predicted. Moreover, the cheap rents are disappearing. The Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies reports that since 2012, the U.S. market lost 6.1 million units renting for less than $1,000.

Lower-income renters are the most financially fragile. According to Habitat for Humanity, 45% of Virginia renters earning $50,000 or less a year, are paying at least half their monthly income for housing.

In another indication that renters showed the first signs of stress in the housing markets, estimates show that 10% of homeowners fell behind on mortgage payments during the pandemic, while 20% of renters fell behind. Pandemic assistance included a moratorium on evictions, plus federal assistance for renters facing homelessness. In Warrenton, families forced to vacate their homes were checked into the Rip Van Winkle Motel on Broadview Avenue, as well as other modestly priced tourist facilities. A church visitor to the various Rip Van Winkle residents recalls families of four sharing take-out meals in the rooms, with the children attending local schools and parents heading off for jobs. The COVID relief programs, including the motel arrangements, began winding down in 2022.

According to the Foothills Housing Network, a point-in-time homeless count on the same night each January reveals an upward trend in Culpeper, Fauquier, Rappahannock, Orange and Madison, with a small drop last year. There were 146 homeless individuals in these counties in 2018, rising to 280 in 2022. The count edged down to 275 in 2023.

One indication that there are unusual stresses at work: within the 2023 homeless count of 275 were 93 individuals who had never been homeless before. Increases were reported among persons over 60, veterans and school-aged children.

Community Touch, a nonprofit that assists Piedmont residents with transitional housing and tools for becoming self-sufficient, is finding more needs from elderly clients. Program director Felicia Champion cited an elderly couple recently priced out of a home they had rented for decades after the long-time owner sold the property. When both the new owner, and other potential landlords demanded rent considered too high to pay, the pair showed up at a homeless shelter. Community Touch helped find an affordable rental, at least for the time being.

Mortgage discrepancies

When rural households feel ready to leave rentals behind and buy a home, the Housing Assistance Council found, “affordable mortgage sources are often more difficult to obtain in rural areas than in cities or suburbs,” partly because there is “less competition among lenders.”

Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve Board’s assault on inflation centered on steady hikes in interest rates. In April 2012, a 30-year fixed rate mortgage was available at a rate of 3.80%. In April 2023, that rate had jumped to 6.28%. Mortgage applications nationally fell by half in 2022. However, in many markets, because of tight supply, the declining appetite for borrowing and buying didn’t result in a fall of home prices. Today, inflation numbers are far less worrisome, and the Fed is on track to reduce interest rates, making mortgages less expensive.

The NIMBY problem

Apartment complexes and other multi-family structures stand out as far more affordable to lower income households than single family homes on large lots. But Brookings’ Schuetz said in her recent congressional testimony that “three quarters of the land in U.S. cities and suburbs is reserved exclusively for single-family detached homes, meaning that row houses, duplexes, and apartment buildings of all sizes are simply illegal to build.”

And even in areas where multi-family structures can go up, lengthy public hearings ignite NIMBY – “Not In My Back Yard” – movements that block more diverse housing patterns or, at minimum, make projects more expensive. Local governments hold most of the authority over housing questions, and are sensitive to citizen groups that prefer neighborhoods to stay the way they found them.

This proposed site plan for Hero’s Bridge Village shows the configuration of 22 L-shaped duplexes on the lot across from Church and Moser Streets in Warrenton.

In Warrenton, a plan for building 44 affordable rental homes for veterans on five acres owned by the Warrenton United Methodist Church required a zoning change. At a public hearing, Daryl Hawkins, a longtime resident living near the site of the proposed Hero’s Bridge Village, declared, “We don’t need what you all are trying to do to us there.” He called on the project’s planners to “find somewhere else.”

Another neighbor warned that the new residents would bring problems of “post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and substance abuse.”

The project was ultimately approved and recently received a $1 million federal grant.

In Rappahannock, public hearings surfaced resistance to the limited affordable housing element for the multi-use development of Rush River Commons in Washington. And when the Board of Supervisors accepted a small boundary adjustment to accommodate a second phase for Rush River, the developers had to agree that for the time being there would be no further housing built on the land that would be added as a result of the expansion.

About this project

Part One: A nationwide housing shortage brought down to the local level shows that homes are scarcer, costlier and more likely to be beyond the financial reach of teachers, health aides, elderly on fixed incomes and young adults.

Part Two: Community Voices: Across the three counties —Culpeper, Fauquier and Rappahannock — young families, elderly and underemployed residents tell how the housing squeeze left them cornered.

Part Three: Emerging solutions show nonprofits, government and the private sector at work in a spirit of innovation and compassion. But the partnerships, financial arrangements and political approvals require commitment, carefully structured teams and patience.

This three-county series is a Foothills Forum collaboration with journalists from the Piedmont Journalism Foundation, Fauquier Times, Culpeper Star-Exponent and the Rappahannock News.

The series is funded in part by a grant from the PATH Foundation. In compliance with Foothills Forum’s Gift Acceptance Guidelines, PATH had no role in the selection, preparation or pre-publication review of these stories.

Foothills Forum is an independent, nonpartisan civic news organization whose mission includes providing in-depth explanatory reporting on issues of importance to the region’s citizens.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.