Sustainability-linked loans are in everyone’s interest

The challenge of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050 will mean transforming the entire UK economy – and the role of the banks will be crucial in the transition

In January, Cartrefi Conwy, a Welsh social-housing landlord, secured a £22m loan facility from Lloyds Bank to help build 1,000 low-carbon, energy-efficient homes.

The project stands to give a much-needed post-pandemic boost to the economy of north Wales. But Cartrefi Conwy, a not-for-profit organisation, will also receive interest-rate reductions on the loan if it meets specific social and environmental milestones, including on its existing homes.

“We recognise how important it is to support the communities living in our existing properties,” said Andrew Bowden, chief executive of Cartrefi Conwy. “This funding will also be used to improve their houses and make them more sustainable, future-proofing them for years to come.”

As the UK faces the challenge of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050, attention has turned to the banking sector’s role in providing innovative new products to help finance that transition.

“We don’t have a conversation today on the financing agenda that doesn’t involve an environmental, social and governance dimension,” says Scott Barton, managing director, Corporate & Institutional Coverage, Commercial Banking at Lloyds Bank. “We are absolutely focused on the transition, working sector by sector and client by client to establish a roadmap around transition.”

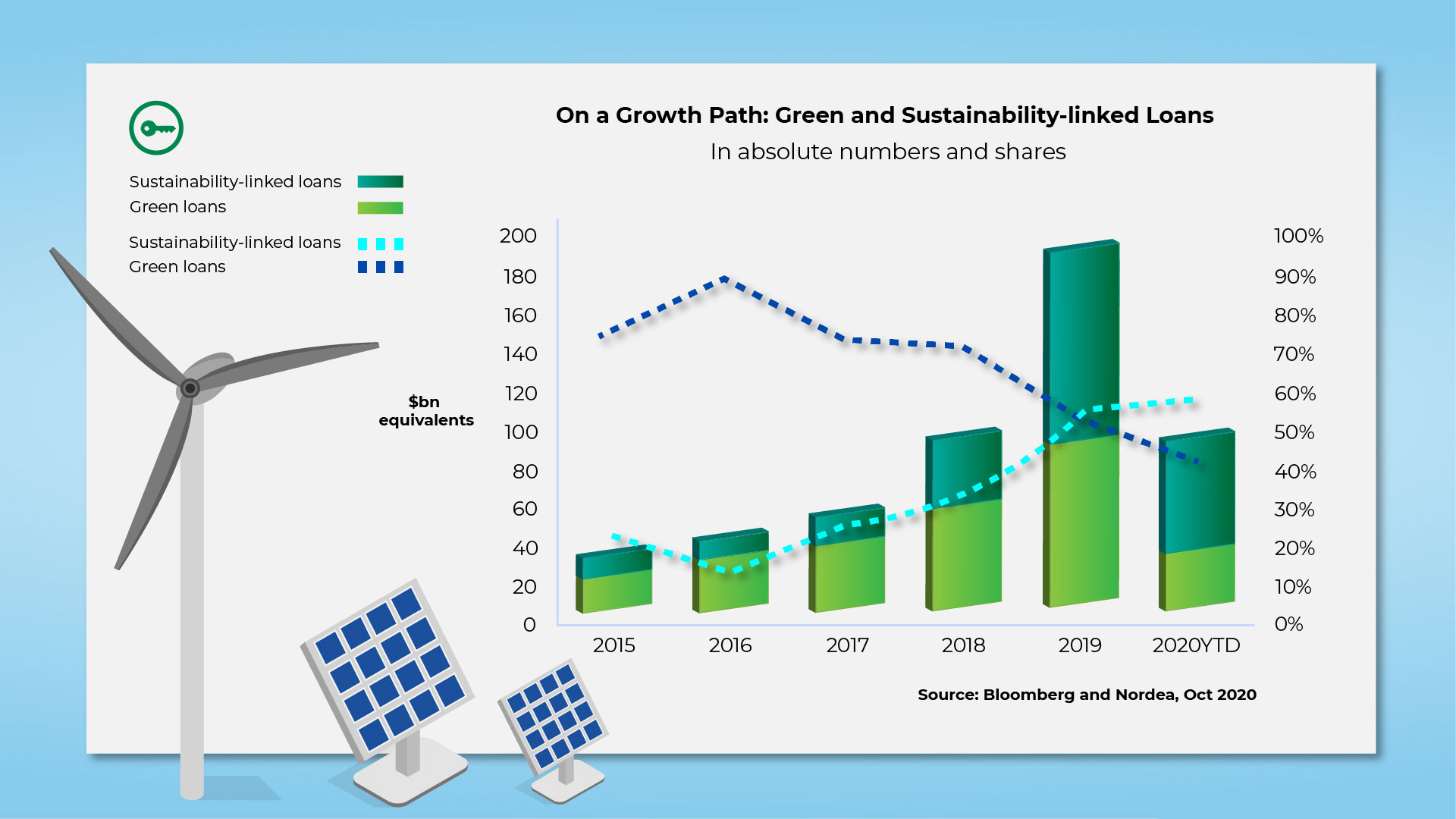

Across UK banking, the market in green and sustainability-linked financing is growing at an estimated 80 per cent, making it among the fastest-growing segments of the credit market.

Sustainability-linked loans, such as the one for Cartrefi Conwy, differ from green financing in that they provide general purpose facilities rather than directly funding green projects. The loans come with incentives for the borrower to commit to defined key-performance indicators in environmental, social and governance areas – and with reductions on the cost of borrowing if and when those KPIs are met.

Jonas Persson, managing director, head of Sustainable and Natural Resources at Lloyds Bank, argues that establishing such financial incentives could have huge potential reach within the economy, touching almost every sector and household.

Sustainability-linked loans, differ from green financing in that they provide general purpose facilities rather than directly funding green projects

“Much attention has focused on green projects, which are an essential component of the transition to a net-zero economy,” he says. “But sustainability-linked loans can be created for every single client, not just green developers.”

Given the size of the task, that is just as well: according to the G20, $90tn of investment – more than four times the GDP of the US – is required between now and 2030 to meet global sustainable development and climate objectives.

For the UK, the government estimates that some £70bn needs to flow into green investments every year to reach carbon neutrality by mid-century.

The wider potential reach of sustainability-linked loans compared with financing green projects is important because some of the biggest contributions to greenhouse gas emissions are not directly related to the energy sector, which is often most associated with global warming.

In the UK, for example, the built environment is responsible for an estimated 40 per cent of all greenhouse gas emissions, while transport accounts for around a third of all carbon-dioxide emissions.

That, argues Mark Carney, the UK Prime Minister’s finance advisor for this year’s COP26 climate conference in Glasgow, and United Nations’ special envoy for Climate Action and Finance, means that financing the shift to carbon neutrality must look beyond the usual suspects. “Achieving net zero will require a whole economy transition, involving every company, bank, insurer and investor,” he says.

Dr Jeremy Gorelick, strategic advisor for the Green Finance Institute, argues that the ultimate goal is to have sustainability-linked loans and other financial products geared towards reducing carbon emissions meaningfully incorporated into the entire banking industry. “What we talk about today as green finance will eventually become just finance,” he says.

Some issues still need resolving. Sustainability-linked loans can be more complex than traditional loans because of the additional targets involved – as well as how those targets are defined and measured. Many financial institutions also want more help from central banks to reduce their borrowing costs and, potentially, to pass those savings on to clients in the form of bigger incentives.

Achieving net zero will require a whole economy transition, involving every company, bank, insurer and investor,

Even so, bankers say that sustainability-linked loans could play a critical role in helping the industry decarbonise its loan portfolios as it looks towards net zero and as the Bank of England prepares for this summer’s stress-testing exercise to assess the impact of climate-related risks on the financial system.

Some banks have already taken a lead. Last year, Lloyds Bank announced an ambitious goal to reduce the carbon emissions it finances by more than 50 per cent by 2030.

Several financial institutions that have already made commitments to decarbonise their loan portfolio say the pledges will inevitably force difficult decisions on how to allocate future funds.

But Lloyds Bank’s Scott Barton insists the shift to net zero is more about making good choices than tough ones. As he puts it, “The more we can incentivise our clients and the more we can provide support for the financing of their activities to drive change, the more we will make a contribution to the government’s overall goals.”