Why rape survivors and exonerees went on a retreat together

A rape survivor, attacked at knifepoint when she was 12, sat across from two men who'd been wrongfully convicted of sexually assaulting children.

The woman, Tomeshia Carrington-Artis, was devastated two decades later when she learned that the man she was sure had been her attacker, was innocent. After his exoneration, people accused Carrington-Artis, now in her late 40s, of intentionally sending the wrong man to prison and said she should be behind bars.

Carrington-Artis and the men she sat with were attendees at a retreat organized by the nonprofit organization Healing Justice — the 17th retreat the nonprofit has held. Crime victims and exonerees come together at the three-day retreats to learn from one another, share stories, play games, and heal.

"There's something powerful and healing"

Healing Justice was started by Jennifer Thompson, a rape survivor who was certain that police suspect Ronald Cotton had been her attacker. Thompson testified against Cotton in court and was relieved when he received a life sentence. But Cotton was innocent. After 11 years in prison, DNA evidence identified the actual rapist, who had not been in the initial lineup, and Cotton was exonerated.

Thompson, wracked with guilt, asked to meet with Cotton and apologized. For years, she has spoken to police and prosecutors around the country, sometimes together with Cotton, about how to make wrongful convictions less likely to happen.

She also created the nonprofit organization Healing Justice in 2015 to help all groups harmed by wrongful convictions. The organization now works to heal the wounds left behind when the justice system gets it wrong.

"There's something powerful and healing when an exoneree can hear what the victim in their case must have felt like," Thompson said. "And for crime survivors, it's really healing to also hear about the experiences of exonerees."

60 Minutes does not normally identify sexual assault survivors, but the women in this piece chose to be identified and are speaking out about the impact wrongful convictions have had on their lives.

The impact of wrongful convictions on crime victims

Nearly 3,500 people have been exonerated so far in this country, according to the National Registry of Exonerations. The day an innocent man or woman walks out of prison is generally a day of rejoicing — it's the day those who've been wrongfully convicted and their families have been dreaming of and praying for.

"They're on the court steps, and their arms are raised high," Thompson said. "It's a day of celebration. But for the crime victims, for the murder victim family members, they're sitting back here saying, 'Hey, hold up a second: This is another nightmare, on top of a nightmare.' The victims have been forgotten."

That post-exoneration nightmare came in the form of both guilt and blame for Penny Beerntsen, who'd been sexually assaulted at age 36 as she went for an afternoon run along the shore of Lake Michigan.

"The first time I went out in public, a friend came up to me and said, 'I can't believe you're showing your face,'" Beerntsen said.

Studies have shown that when the actual perpetrator is not in the police lineup, witnesses often pick the wrong man, who then comes to replace the original offender in their memory of the crime. In Beerntsen's case, as in Thompson's and Carrington-Artis', the actual perpetrator, revealed by DNA evidence years later, was not in the original lineup.

The narrative many people then see is that a false accusation — suggesting a lie — sent someone to prison, Thompson said.

"Why would a crime survivor, why would a victim, want the wrong person to go to prison?" Thompson said. "That doesn't make any sense at all."

An exoneration can also be traumatizing for the families of murder victims, even if the family members played no role in identifying the wrongfully convicted person.

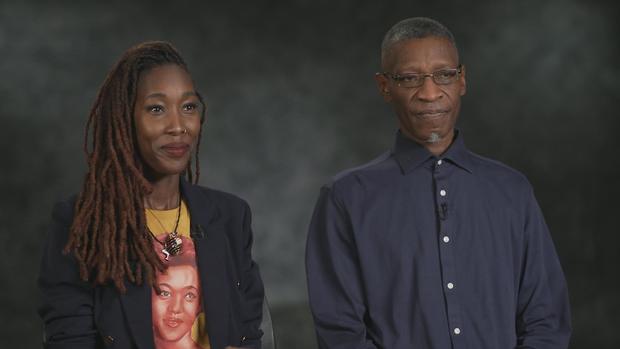

It was a new nightmare for Andrea Harrison and her father, Dwayne Jones, years after the 1987 rape and murder of Andrea's mother, Jacqueline, when the man police had told them was guilty of the brutal crime, was exonerated. Larry Peterson spent more than 17 years in prison before DNA testing proved his innocence. The DNA has not led police to the actual attacker.

Harrison and her father feel that since Peterson's exoneration, the original crime and victim have become an afterthought.

"It's always been, 'What do you think about Mr. Peterson?' That is not my charge," Andrea Harrison said. "I care about Jackie. I'm worried about Jackie. What about Jackie?"

The impact of wrongful convictions on exonerees

Exonerees' stories are often filled with egregious police and prosecutorial misconduct. Chris Ochoa, who falsely confessed to rape and murder after abusive police interrogations, said he didn't feel like he fit in anywhere after he was exonerated.

Howard Dudley served more than 23 years in prison, though evidence withheld by prosecutors likely would have cleared him of the charges.

"I always dreamed of being there with my kids: see the football game, see them on the basketball court," Dudley said. "Didn't get a chance to see none of that."

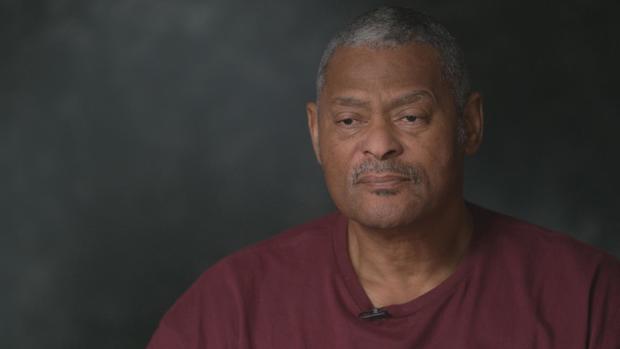

Exoneree Raymond Towler said he struggles with the lingering stigma, and hurt, of being charged with such a heinous crime: child rape. DNA testing finally proved Towler's innocence and won him his freedom after 29 years in prison. He said being released was thrilling, but also daunting. The adjustment was a challenge.

"I couldn't even really go out the door by myself," Towler said.

A wrongful conviction hurts many more people than just the man or woman who ends up behind bars, Thompson said. She compared wrongful convictions to bombs, rather than single bullets.

"It's not just Raymond Towler got hurt. Like, his whole family got shrapnel. And the victims got shrapnel," Thompson said, noting that the community as a whole was also hurt because a child molester remained free while Towler was wrongfully imprisoned.

Exonerees and survivors, healing together

Towler attended a Healing Justice retreat along with Carrington-Artis — the woman who was raped when she was 12 — and Andrea Harrison and her father, Dwayne Jones, who lost their mother/partner to rape and murder. Towler was scared coming to the retreat, not knowing if he'd be met with hate.

"Because, you know, nobody believed me for, you know, 30 years," he said.

From the other side of the table, rape survivor Loretta Zilinger-White worried that exonerees blamed crime victims in cases like her own. DNA cleared the man who'd been convicted in her case but has not identified who the actual perpetrator was. She said she relives the assault daily and can't get the exonerated man's face out of her memory.

"I feel guilty," she said. "Because I feel like I did something wrong."

Zilinger-White asked Towler about it.

"You didn't do anything wrong," he said. "It's not your fault."

Retreat attendees smash bowls with a hammer, then glue them back together. Once the bowls are repaired — a process much more challenging than breaking them — the attendees paint the cracked lines with gold as part of a Japanese concept called kintsugi.

"Even in our broken places, we're still beautiful," Thompson said. "Because we're strong at our broken places. And we're not disposable."

Thompson, who did coursework in trauma recovery, leads the group in discussions. Attendees sit in a circle and take turns talking about their losses. On day two of the retreat, Thompson leads an exercise on how the harsh words used against them end up becoming internalized.

"You might have been called a liar. You might have been called a rapist," she said. "And those words really do take on a life of their own."

She had the attendees write letters to themselves "from the space of the critical mind" — letters detailing the awful things they think about themselves. Later, they each write another letter, this time focused on self compassion.

As the retreat came to a close, attendees said they felt courageous, open and nurtured. Zilinger-White said she was finally able to let go of her guilt after her conversation with exoneree Raymond Towler.

It's something Thompson was able to do a long time ago.

"I feel so sad that for 11 years [Ronald Cotton] was in prison for something he didn't do, but I'm also really sad that I got raped at knifepoint and chased around, you know, a neighborhood in the dark while I didn't have any clothes on," she said. "I feel deep amount of sadness for these cases, and for everybody who's impacted by them."