Legendary hockey reporter Stan Fischler writes a weekly scrapbook for NHL.com. Fischler,

known as "The Hockey Maven," shares his humor and insight with readers each Wednesday.

With the NHL announcing it will participate in the 2026 Milano-Cortina Olympics and 2030 Games, Fischler remembers the 1960 Winter Olympics Games in Squaw Valley, California, where the United States performed the first -- but often forgotten -- "Miracle on Ice."

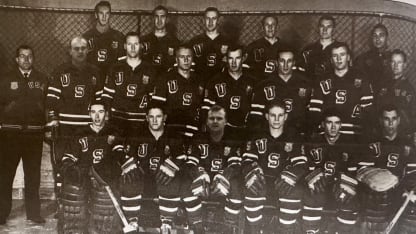

When the United States hockey team prepared for the 1960 Squaw Valley Olympics in what today is Palisades Tahoe, California, the odds were stacked high. Yet 64 years ago to this date, the country won its first gold medal in ice hockey.

For starters, the United States never placed higher than second in any previous Winter Olympics. Furthermore, competition from Canada, the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia and Sweden became much more formidable since the games were resumed following World War II.

"We were definitely underdogs," said United States coach Jack Riley, Jr., on loan from the United States Military Academy in West Point, New York, where he ran the hockey program. "We couldn't possibly win a gold medal. At least that's what they all were saying before we hit the ice."

Riley couldn't have cared less what anyone was saying. He had a job to do and did it with the utmost confidence and grim determination. A Boston native and former Dartmouth star, Riley chose his players from hockey country, New England and Minnesota. He vowed to play no favorites when the team left West Point in mid-January of 1960 on an exhibition tour that included games against college and amateur teams.

"Some of you may not like my decisions," Riley told his players. "But I want us to start the tourney with the best possible lineup."

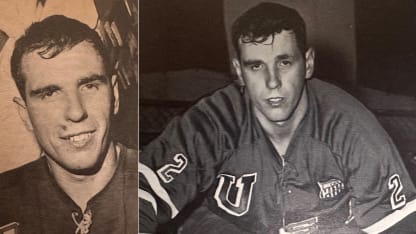

True to his word, Riley cut two of his Army aces, Thomas Harvey and James O'Connor. Larry Palmer, also an Army star, was penciled in as starting goalie, but Riley wasn't happy with Palmer's pre-Olympic work. In a surprise move, Riley turned to an unknown Jack McCartan as starter.

A puck-stopper who learned to play on frigid outdoor rinks, McCartan always felt that baseball was his primary sport.

"Until I finally played in an NHL game after the Olympics," he revealed. "I hadn't seen more than five NHL games in my whole life. I was in awe of the NHL."