A book celebrates James Foley and confronts a man involved in his murder

Irish author Colum McCann and Foley’s mother, Diane, questioned one of journalist’s kidnappers and co-wrote a book about both men

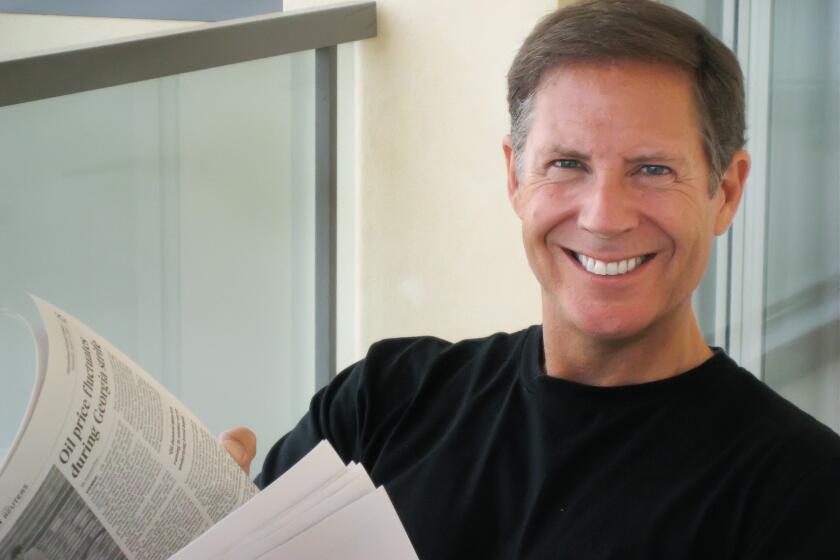

Among the scattered notes taped to the door of the Irish author Colum McCann’s home office in Manhattan is a photograph of James Foley, the American journalist who was murdered by members of the Islamic State in August 2014. In the picture, he leans against a barricade of sandbags in jeans and a flak vest, reading McCann’s novel “Let the Great World Spin.”

McCann was so moved when he saw the image shortly after James Foley’s death that he reached out to Diane Foley, his mother, to offer his condolences — and his help telling her son’s story, should she ever want it. But Foley missed the message.

She was busy creating the James W. Foley Legacy Foundation, an organization focused on protecting journalists and ensuring the freedom of Americans held hostage or wrongfully detained abroad. And she was still grieving a son who had been held kidnapped while covering the Syrian civil war and held for 21 months before he was executed on camera, with the footage then released online.

Then, in 2021, McCann and Foley found themselves on the same Zoom call. It was for a Marquette University book club; the group was reading another of McCann’s novels, “Apeirogon,” and Marquette was James Foley’s alma mater, so his mother had been invited. This time, they connected.

“It was serendipitous,” Foley said, seated next to McCann in his living room, in Manhattan. “Colum reminded me of Jim in a lot of ways, just in his goodness and his ability to put very profound feelings into words.”

Within a month of their Zoom call, McCann was visiting the Foleys’ New Hampshire home to discuss what would eventually become “American Mother,” a hybrid of biography and memoir released in the United States by Etruscan Press on March 5.

“I tried to be in Diane’s head,” McCann said of their collaboration. He would send Foley chapters and she would reply, offering direction, corrections and clarifications.

That McCann was interested in the Foleys’ story comes as no surprise; many of his novels are based on real people and events.

“Let the Great World Spin,” for example, touches on Philippe Petit’s tightrope walk across the Twin Towers in 1974, and “Apeirogon” is about the relationship between Rami Elhanan, an Israeli graphic designer, and the Palestinian scholar Bassam Aramin.

But unlike those books, “American Mother” is a nonfiction account.

“It’s kind of unique in my experience,” said Michael Cunningham, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of novels such as “The Hours” and “Day,” speaking about “American Mother.” “It’s a novelist writing about an actual event with a depth and thoroughness that you never get from the news.” Searching for another such paragon, Cunningham volunteered Truman Capote’s 1966 classic “In Cold Blood.”

Structurally, “American Mother” is an unusual book. Its first and third sections are told from the point of view of an omniscient narrator and focused on a series of exchanges between Foley and Alexanda Kotey, the British-born Islamic State militant who in 2022 was sentenced to life in prison by a federal judge for playing a key role in James Foley’s murder as well as in the deaths of three other American hostages.

As part of his plea deal, Kotey agreed to meet with the victims’ families, should they choose to do so. It was an unusual stipulation, and one Foley was eager to accept.

“I felt it was important to talk to Alexanda because I didn’t want him to think we were afraid of them,” Foley said. “I wanted him to know who Jim was, and I also wanted to listen to his story. Like, what brought him to that point?”

Sandwiched between McCann’s accounts of those meetings is a more traditional memoir, written from James Foley’s perspective. This section is filled with personal details: how he used a flashlight to read Tintin stories under the covers; how he wore a baby blue tuxedo to his senior prom; how, in his 20s, he taught English and writing to young women hoping to earn their G.E.D.s. Other details came to Foley through other prisoners held with her son and later released, such as how his captors forced him and others to sing a parody of the song “Hotel California” that repeated the line “You can never leave,” and how he remained rooted in his faith despite those cruelties, even helping organize clandestine board games to boost morale.

“I just hope that some of it can resonate with anybody who’s lost someone,” Foley said.

The book also has a message, she added — “that, as humanity, we need to build bridges, even with people we can’t stand. We need to have a way to talk to one another.”

Foley’s urge to understand the psychology of one of her son’s captors made her a perfect match for McCann, who has described the value of “radical empathy” to his moral compass.

“He’s a great believer in people coming together and looking into each other’s eyes, and seeing the humanity of each other,” said the actor Gabriel Byrne, a friend of McCann’s. “The reason I think that he was drawn to Diane Foley’s story is because that is a story about connection, and confronting the person that you believe is an unforgivable enemy and trying to find the humanity in that person.”

When McCann saw this photo of James Foley reading his novel, “Let the Great World Spin,” shortly after the reporter’s death, he was moved and reached out to his mother.

Foley met Kotey for three hourslong sessions in a sequestered, windowless room in a federal courthouse in Virginia. No one in her family wanted to join her, Foley said: “They thought it was ridiculous.” But McCann accompanied her each time, and asked Kotey questions as well.

McCann and Foley both recalled the conversations with Kotey as illuminating, upsetting and heartbreaking. In Kotey, Foley found a bright and complicated man, someone who read voraciously and cried when he shared pictures of his daughters in Syria.

“Everyone lost in this, including him,” said Foley, who credits her Roman Catholic faith with helping her maintain compassion for the man who helped kill her son.

“He was much bigger and messier than what I thought he would be,” McCann added. “I like those complications, and I think increasingly, we don’t want to talk about those complications.”

For McCann, the most remarkable moment in the encounters came at the conclusion of the third and final meeting, when Foley reached out to shake Kotey’s hand. To McCann’s surprise, Kotey clasped her hand — an act that would be prohibited under some interpretations of Islamic law. When McCann later questioned Kotey about the exchange, Kotey answered that Foley was “like a mother to us all,” thereby excusing the contact under a familial exemption.

“He’s touched the hand of a woman,” said McCann, “but he’s acknowledged her as a mother.”

Ultimately, Foley’s anger was directed more at her own country than at Kotey. When James Foley was taken hostage, she said she was often left in the dark by a government that maintained a strict policy of not negotiating with terrorists. Foley said she spent years being shuttled between agencies, and was even threatened with prosecution should her family try to pay her son’s ransom. “I was enraged at how our country had treated me, the way they treated Jim’s plight,” she said.

Through her foundation, Foley urged President Obama to reform the United States’ international hostage policy. It was in part on her instigation that Obama eventually formed hostage response groups at the F.B.I. and the National Security Council, and created the position of a hostage coordinator to support families.

“She is pure guts,” said the broadcast journalist Judy Woodruff, who has interviewed Foley several times. “She’s able to look powerful government officials in the face and say, ‘This is what we’ve got to do.’”

More recently, Foley was among those who successfully argued for the passage of the Levinson Act through Congress, which further bolstered resources to bring back hostages.

“What we refer to as the hostage recovery enterprise would likely not exist at all without Diane Foley,” said Roger Carstens, the special presidential envoy at the State Department for hostage affairs. Carstens believes even the Biden administration’s negotiation process to secure the release last year of six Americans wrongfully detained in Venezuela can be directly traced to her advocacy.

“She created the machinery that makes it possible to bring people like them home,” he said.

“American Mother” by Colum McCann with Diane Foley (Etruscan Press, 2024; 256 pages)

Warwick’s and the University of San Diego present Colum McCann

When: 7 p.m. Monday (doors open at 6:15 p.m.; seating is first come, first serve)

Where: Joan B. Kroc Institute for Peace and Justice, University of San Diego campus, 5555 Marian Way, San Diego

Tickets: $10-$26

Online: warwicks.com/event/mccann-2024

Ufberg writes for The New York Times.

Get U-T Arts & Culture on Thursdays

A San Diego insider’s look at what talented artists are bringing to the stage, screen, galleries and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.