With its mix of beige-hued, sheet-metal buildings, the Redmond Air Center adheres like an appendage to the small municipal airport in central Oregon. The otherwise crystal blue sky is carpeted with a thin layer of lazy, low-lying clouds whose color matches the distant white-capped volcanoes that make up the nearby Cascades. It’s from this regional airstrip that the Redmond Smokejumpers—one of nine similar bases across the American West—respond to dangerous fires while still in their smoldering infancy.

If hotshot crews filled with experienced firefighters serve as the front line between calm and calamity, smokejumpers are the vanguard who extinguish remote fires before they become entrenched. For most months out of the year, these veteran firefighters strap on 100 pounds of gear and fling themselves out of low-flying planes to survey and combat fires across some of the United States’s most rugged wilderness.

“Smokejumpers are looked to for leadership on fires,” Pete Lannan, former smokejumper and current national smokejumper program manager, tells Popular Mechanics. “The real strength of the smokejumper program is aggressive initial action in either remote or far–reaching places.”

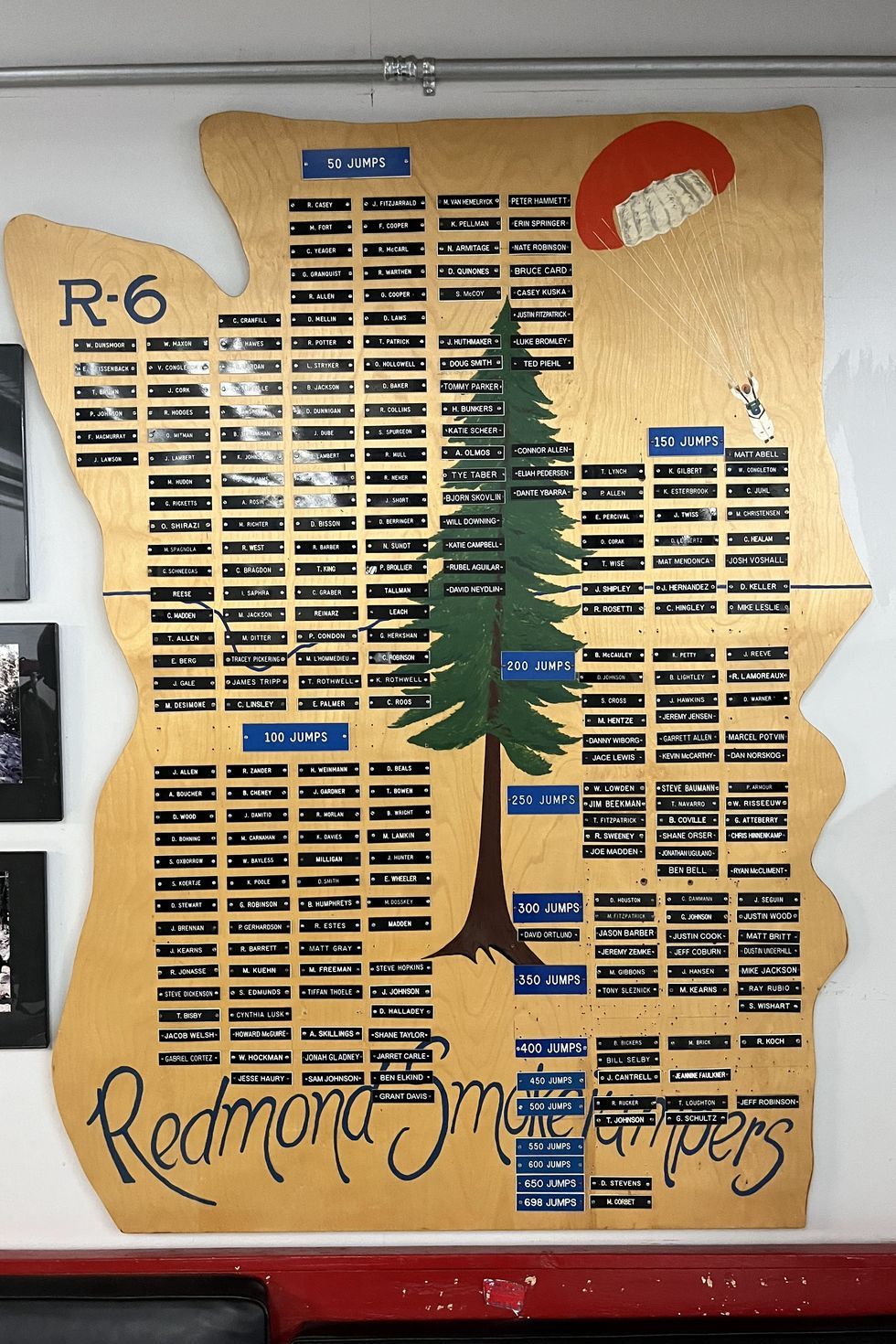

For over 84 years, around 6,200 men and women—whether conscientious objectors, ex-military paratroopers, adventurous college students, firefighting professionals, and even one Apollo astronaut—have served in this exclusive and physically demanding role. And while the job has remained similar throughout the decades, smokejumper crews across the country are adapting to the fiery times of the here and now as the firefighting season slowly lengthens.

But on this cool autumn day, things are quiet, and the U.S. Forest Service’s white-and-orange Sherpa C-23B aircraft are asleep in their hangar. Seasonal rains came early this year, signaling the end of the fire season and finally quenching this stretch of the sun-parched West—but the work isn’t done. Instead, the Redmond Smokejumpers are training, repairing, building, and preparing for the fires that eventually will come, as they always have in this fire-prone part of the world.

A Fiery History

In western North America, fire isn’t a flaw, but a feature. Fires have regularly burned across this stretch of country for thousands of years as warmer, drier climates arrived at the beginning of the Holocene epoch 12,000 years ago. Even embedded in some western trees are various strategies to survive low- to medium-intensity fires, whether it’s the thick bark of ponderosa pine or the fire-activated seeds of lodgepole pine.

Although sedimentary charcoal data varies over the millennia, scientists have found a noticeable uptick around 5,500 years ago as native peoples used fires for hunting, maintaining fields, and nurturing crops. And that human relationship with fire continues to modern times, though in vastly different circumstances. In response to severe fires in the early 1930s, the Forest Service established an aggressive fire suppression strategy known as the 10 a.m. rule, dictating that all fires needed to be put out by 10 a.m. the day after the initial report.

This aggressive call to action coincided with another innovation: airplanes. In 1934, Russia began an experimental program called the Russian Aerial Fire Protection Service—and the Forest Service knew a good idea when they saw one, says Smokejumper Magazine editor Chuck Sheley.

“They went up to Winthrop, Washington, in 1939, and said ‘we’re going to copy the Russian smokejumper program.’ They didn’t say that exactly, but the Russians had already been doing it for five years,” Sheley says. A former smokejumper in the 1960s out of the now-defunct Cape Junction base in Oregon, Sheley is now a steward of smokejumper history, writing books and articles about the men and women who have taken on this dangerous job over the past 84 years. “They did a month-long research program—60 or so jumps—and they proved you could safely drop a person from an airplane into a forest and get people on the fire.”

On July 12, 1940, the first operational jump in the U.S. took place in the Nez Perce National Forest in Idaho. With the ability to drop people directly on a wildfire, the 10 a.m. rule was now realistically attainable. Over the next 84 years, the program would experience major changes that Sheley sees as roughly five major eras of smokejumper history.

While the circumstances surrounding a smokejumper’s initial enlistment may have changed, the kind of person drawn to this fiery line of work has remained remarkably constant throughout these disparate generations.

“The best thing about smokejumping is the people,” Sheley says. “It was such a select group of individuals, and you don’t know how they all came together… Besides being highly physically fit, they were entrepreneurial type people—people who liked a challenge.”

The Challenge

Even when empty, the ready room at the Redmond Air Center seems to hum with an energy—that the gear resting among the racks could be zipped, strapped, tucked, and ready to jump at a moment’s notice.

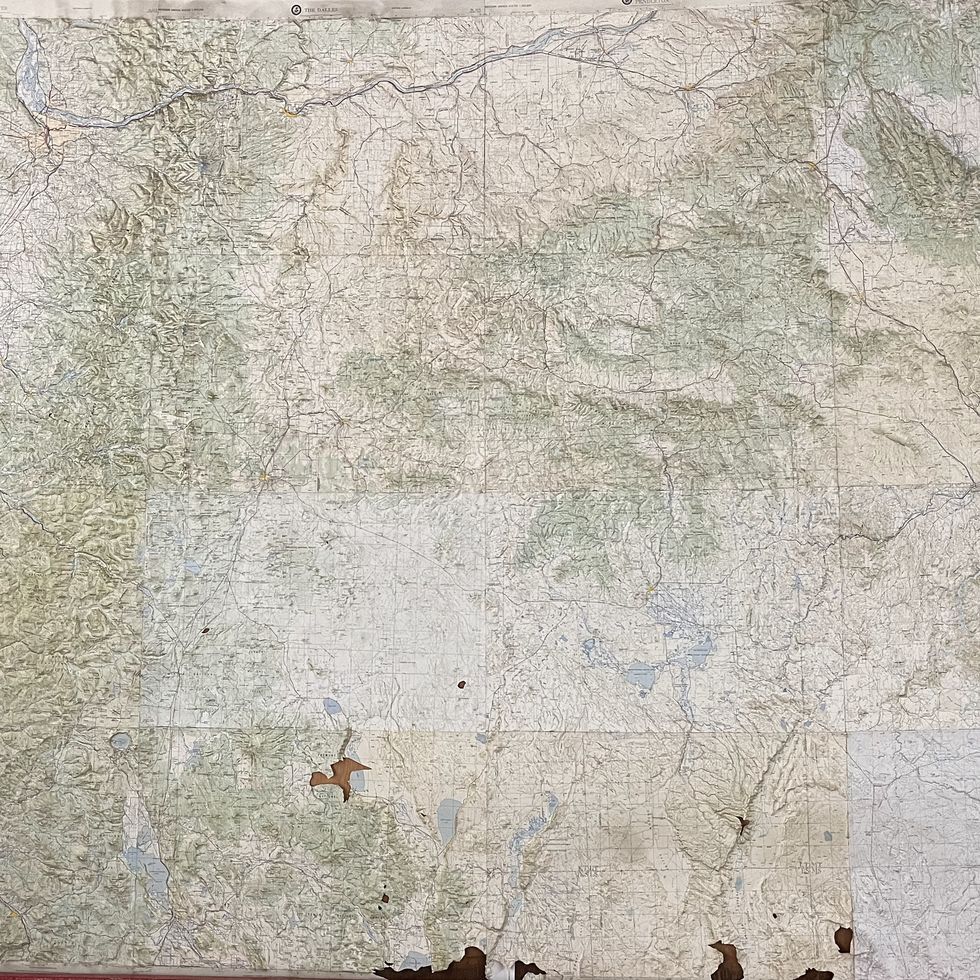

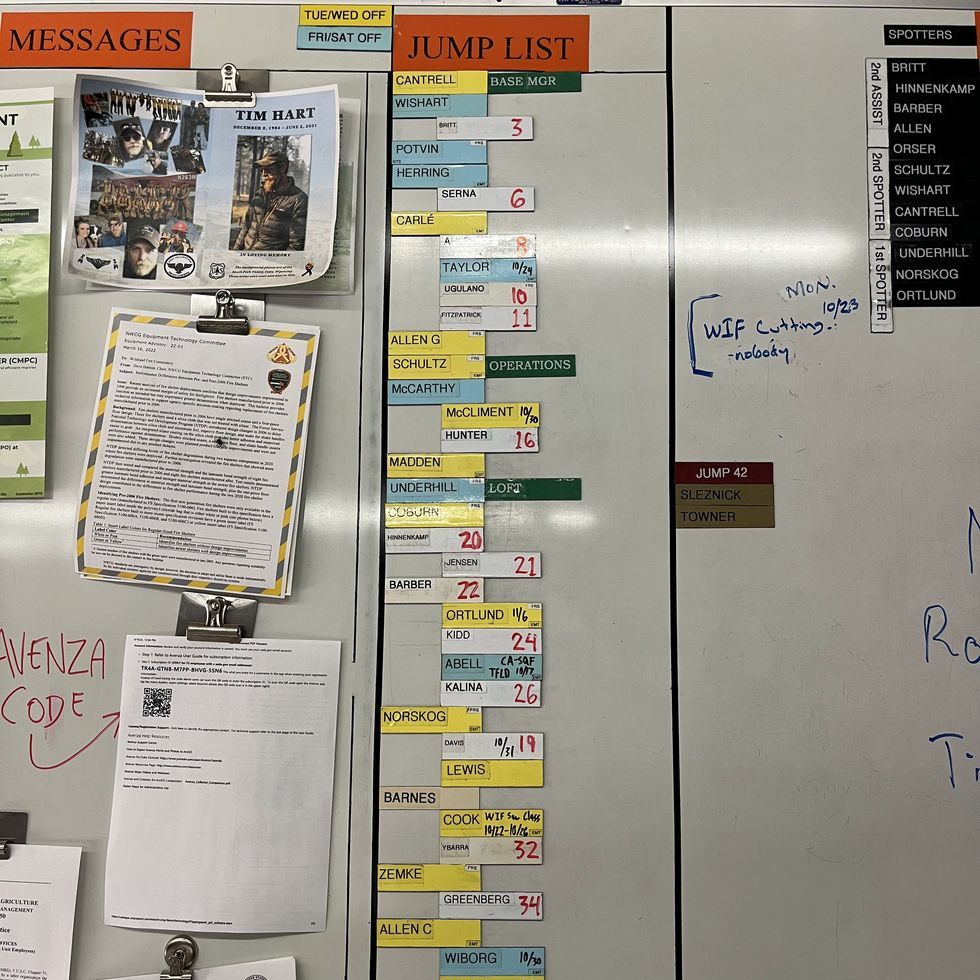

Base manager Josh Cantrell stands in the room’s center with a wall-sized map of the Pacific Northwest behind him, and to his left, pinned to a whiteboard, is the jump list. During the fire season, this simple list details who among Redmond’s 50 smokejumpers is on deck to jump a fire.

“If we have an initial attack or a jump request, the siren goes off… the first 10 people available on the list would run in here and get in their gear,” Cantrell says. “This ends up being the hub of everything—weather briefings happen here, all operational things start here.”

Today, every rookie smokejumper already has several years of experience fighting wildfire, likely serving much of that time on a hotshot crew. By the time they enter training, smokejumper rookies have already learned the finesse of wielding a Pulaski, understood how to separate fuels, and mastered the art of fire breaks. The only difference between a hotshot and smokejumper is the mode of transportation—but it’s a big difference.

“[Smokejumping] is the hardest training you can do with the Department of Agriculture. Historically, one-third to one-half of every class doesn’t make it,” Patrick McGunagle, a former smokejumper out of the West Yellowstone base and current USAF forestry technician, tells Popular Mechanics. “Each base has their own traditions during their rookie training.”

To graduate, each rookie smokejumper performs 25 successful jumps using a ram-air parachute—a recent upgrade from the classic round parachutes of Sheley’s era. Having received Air Force training, McGunagle was more than familiar with the ins and outs of parachuting, but the intensity of smokejumper training still came with a few surprises.

“Within the first 48 hours, I’m 60 feet up in a Ponderosa pine tree… we have to climb this tree that you can’t even reach around at the base until you can get your hand around the tree, so you’re way up there,” McGunagle says. Smokejumpers have to climb trees to retrieve supplies—or fellow smokejumpers—that get tangled up in the towering pines that dominate the American West. “It’s just a battery of stressful events all day long. You’ll go from tree climbing, and your arms are still all gripped out so you can’t even hold a pencil, then you go to the classroom to learn about your harness or parachute.”

Once a smokejumper graduates the six-week-long training program, repetition is the name of the game. Along with those initial 25 training jumps, Cantrell estimates that a rookie smokejumper will see around 50 jumps in that first season to really hammer things home. But these aren’t the wide-open fields that are the preferred landing zones for sport jumpers; these spots are smaller, rougher, and tighter areas designed to test a smokejumper’s abilities.

“We are generally not training people how to fight fire. We’re just teaching how to jump out of an airplane and function in a small group tactic situation,” Cantrell says, standing amidst the customized gear of the base’s 50 smokejumpers, as if some ghostly firefighting regiment was standing at attention. “You can get accustomed to 19 of your best friends going to suppress a fire, but it may just be you and me now. If a chainsaw breaks, we need to figure out how to do it. If the cargo is hanging up in a tree, we’ve got to go deal with it.”

With these lessons learned, a new rookie is ready to jump their first fire.

The Jump

Two C-23B Sherpas rest quietly inside the Redmond Air Center hangar, whose walls are lined with tools, propellers, and other replacement parts. One engine is ripped open for off-season repairs, the other sits ready. Inside, boxes of supplies rest along the port side of the fuselage, along with 10 seats lining the starboard. Meandering footsteps echo throughout the cramped cabin as Cantrell points out all the features vital to a successful fire jump.

“This is us. Configured for 10 smokejumpers, two spotters… and two pilots up front, we’ll take off with 14 people,” Cantrell says.

Once smokejumpers get the call from the Central Oregon Interagency Dispatch Center, or COIDC, which coordinates fire suppression efforts in central Oregon, they pile into these 10 seats after all gear and safety checks are complete. After communicating with local dispatches and discussing a potential landing zone with the smokejumper serving as incident commander, spotters will release streamers at around 1,500 feet to determine wind speed and drift.

“We’re going to fly over the jump spot and kick out streamers… they’ll travel downwind, and we’ll visually measure the distance from the landing spot,” Cantrell says. However, things get tricky with a variable airmass, where streamers perplexingly travel in two different directions. This, according to Cantrell, is where art collides with science. “Sun that started in the East is now in the West and is heating that slope, and it could affect that airmass.”

Once spotters and jumpers work out a landing zone, the first two smokejumpers will do what they do best—jump. While C-23B Sherpas include a rear ramp for loading and unloading, smokejumpers exit through a side door near the back at around 3,000 feet. After a roughly two-minute flight to the ground, smokejumpers will assess the situation and radio back to the plane to confirm that the jump spot is adequate. With the average smokejumper-per-fire rate out of Redmond being 5.6 in 2023, more smokejumpers will follow the first pair to the ground as needed.

Finally, once all smokejumpers are on the ground, the Sherpa will make one last circling descent to 1,500 feet to drop the necessary cargo, including water and other tools. Because this cargo is vital for both fire suppression and survival, this is where a smokejumper’s tree climbing abilities get put to the test. But once retrieved, these experienced firefighters get to work putting out smoldering fires supplied with enough food and water to keep them going for 48 hours.

Of course, arriving at a fire and suppressing it is only half the battle. There’s also the return trip to consider, and this can be even more arduous than the death-defying methods it took to arrive at the fire in the first place.

“I’d say a light pack out is somewhere in the 130- to 135-pound range—that’s all your gear,” Lannan says. “It’s not uncommon to get your gear flung off by a helicopter… certainly not uncommon to get a helicopter ride, but there are still what we call pack outs.”

Sometimes prompted due to a lack of aircraft availability, these intense hikes, which can stretch more than a dozen miles, limit unnecessary incursions into the remote wilderness, large swaths of which remain untouched by humans.

And smokejumpers aim to keep it that way.

The Future

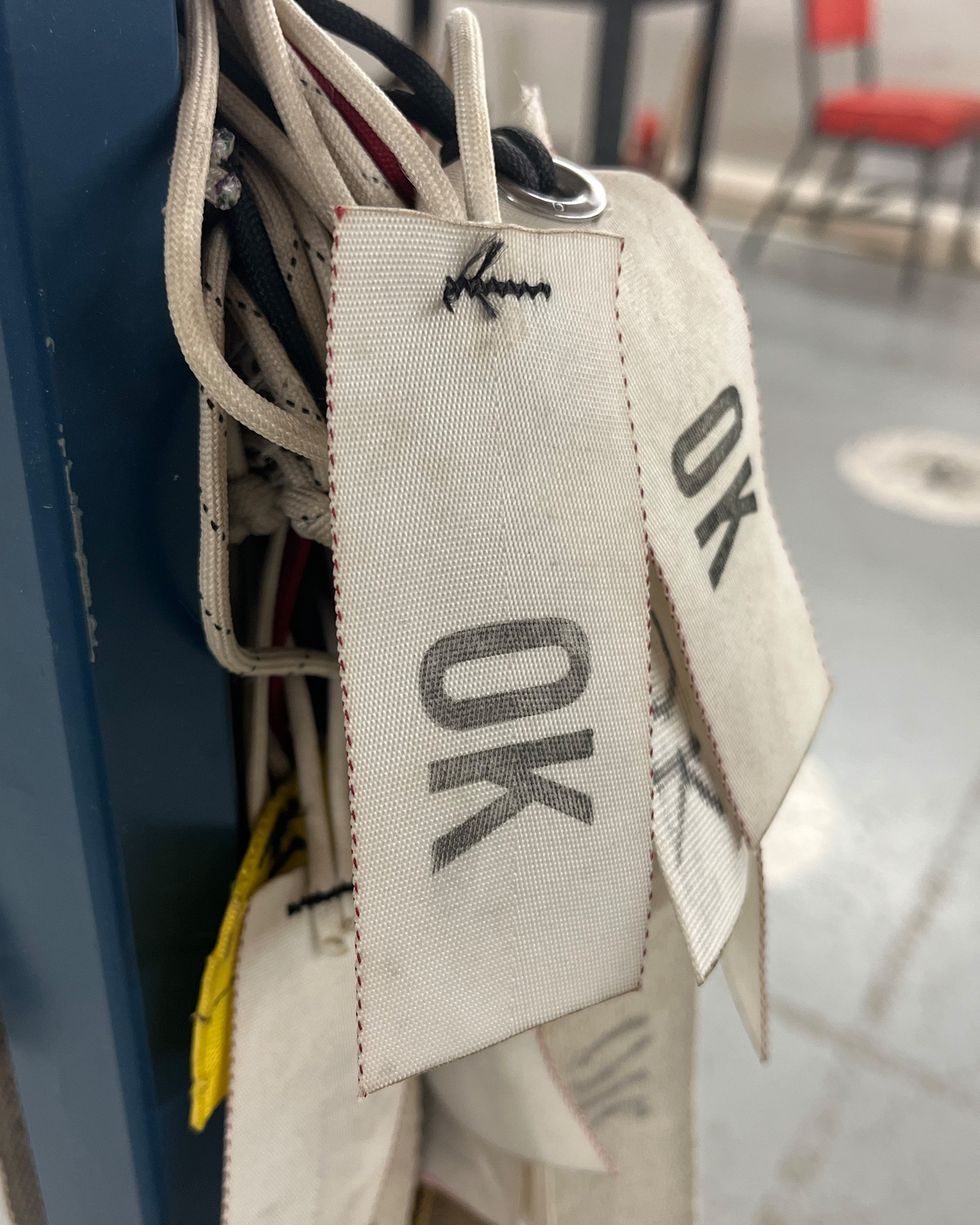

Back in the Redmond “loft”—the smokejumpers’ nickname for their base of operations and a reference to the high-ceilinged loft where parachutes are dried out, cleaned, and inspected—the distant clang of a bench press echoes down the hall while Cream’s "Sunshine of Your Love" blares in the nearby rigging room. Filled with parachute-shaped tables some 20 feet long, this is where ram-air and emergency parachutes are packed and sealed with the rigger’s approval.

“We jumped 33 fires this year—that’s 187 folks out the door,” Cantrell says. “Our workload is based on how much lightning we get, and if we don’t get abundant lightning, we do other stuff.”

Adjacent to the rigging room is the sewing room with dozens of sewing machines lining the walls. In one corner is a bin filled with various buckles, straps, and loops, while in the center of the room are bolts of fabric ready to be purpose-built into firefighting gear. Because smokejumping equipment is so specific to the mission, it’s easier for the men and women doing these fiery jumps to sew up and repair their own stuff rather than relying on a third-party service. So while fires aren’t raging, the sewing machines are.

“You’re laying out, you’re cutting out, and you’re building stuff. It’s pretty fun,” Cantrell says. “It’s something that you can realize the rewards of because you’re then wearing it, you’re using it.”

Requiring lots of on-the-job training, intense physical requirements, irregular hours, and years of previous wildfire forestry skills, smokejumping isn’t for everyone. And like many positions across the forest service, recruitment and retention has been a logistical fire the smokejumper program hasn’t quite doused.

And other changes may be on the horizon. New aircraft acquisitions, especially Black Hawks for firefighting helicopter repeller crew, could affect the need for delivering initial attack wildland firefighters by plane. But for now, if you need to quickly put out a fire in the most remote parts of the country, smokejumpers are the solution.

Today, some 450 smokejumpers still protect the U.S.’s most wondrous locations, while many more, like Sheley, Lannan, and McGunagle, have moved on to other jobs both in and outside the forestry service. But wherever their lives may take them, they always remain a part of the nation’s most elite firefighting force.

“Some of those guys who’ve rookied in the 50s, they’re still smokejumpers today,” McGunagle says. “You never stop being a smokejumper.”

Darren lives in Portland, has a cat, and writes/edits about sci-fi and how our world works. You can find his previous stuff at Gizmodo and Paste if you look hard enough.