The Rich Black History That Runs Through Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

My maternal grandfather, who we lovingly called Poppy, is a country boy from Ohio who loved horses, westerns, and good music, especially jazz, gospel, and country. Though he gave up on dive bars as a young man, Poppy was rarely seen without his cowboy hats. I, on the other hand, never really liked country music. In fact, I used to take pride in my affinity for R&B and rap music, because I thought those genres alone were an extension of my Blackness. I’ve said the same about many other genres of music like rock, house, and EDM, which I ignorantly referred to as “white people music.”

That’s not to say that I’m unaware of the Black American story behind most popular music. Because of my Poppy, I know what Miles Davis and Louis Armstrong did for jazz, as well as what Big Mama Thornton, Jimi Hendrix, Tina Turner, and Chuck Berry did for rock and roll. But whitewashing and erasure disrupt that storied tradition and pushes many young Black people, myself included, away from genres that our ancestors danced, sang, and relaxed to. With her new album, Cowboy Carter, Beyoncé changed that trajectory for millions, reminding us all that Black country artists have always led the field and have used country music to vent and navigate being Black and working-class in America.

Unfortunately, the invisibilization of Black country artists has created an industry where bona fide country songs from said artists are instead labeled R&B, pop, or rap. Despite more Black Americans living in the South than any other region of the nation, there is an assumption that we only listen to “urban” music and cannot relate to anything else. But Beyoncé pushed back, creating an album that is true to her roots and resists the monolithic portrayal of Blackness. Country, original rhythm & blues, blues, zydeco, and Black folk music influences—these are the sounds she heard at rodeos, on the radio, and in her home. The album officially took five years to make, but it really is a reflection of Beyoncé’s whole life. It’s her truest project, which the singer calls “the best music I’ve ever made.”

“[This album] was born out of an experience that I had years ago where I did not feel welcomed...and it was very clear that I wasn’t,” Beyoncé wrote in an Instagram caption. “But, because of that experience,” she continued, “I did a deeper dive into the history of Country music and studied our rich musical archive.” The instruments used—like fiddles, Hammond B-3 organs, washboards, steel guitars, accordions, and harmonicas—draw on ancestral techniques, creating what her team calls a “gumbo of sounds.” Rhiannon Giddens, a Black and Indigenous country artist, is also a music historian who has made it one of her life’s missions to remind people that the banjo is an African diasporic creation. Giddens’ banjo strums are what welcome listeners to Beyonce’s “Texas Hold ‘Em.”

The features and references peppered throughout the album are also proof of Beyoncé’s extensive research. On an interlude called “Oh Louisiana,” Beyoncé samples and remixes Chuck Berry, the “father of rock and roll” who transformed rhythm and blues into something new entirely. Throughout Cowboy Carter, Beyoncé gives breath and life to the legacies of many Black musical geniuses, from Berry to Stevie Wonder to Linda Martell, the first Black woman artist to be commercially successful in the country genre. At the beginning of her career, South Carolina-born Martell sang pop and R&B but ultimately signed with white-owned Plantation Records and formally switched to country. It was considered a risk at the time, but the pivot didn’t come hard for Martell. The music was Black and true to her Southern roots. Against the advice of others, who suggested Martell remain in the box Black artists were expected to create within, she continued to bring together the guttural wails of gospel music with the storytelling of country and the honesty of the blues.

After securing a few top 40 country hits, Martell felt her record label wasn’t investing in her career as much as their white artists. She tried to leave the label due to the racism she endured and attempted to work with new production teams on the next phase of her career. Plantation Records, true to its name, wouldn’t let Martell go—though she had fulfilled all of her contractual obligations—and Martell was blackballed. Hearing Martell’s voice on Cowboy Carter feels like destiny fulfilled and divine retribution. In her introduction of “Spaghettii,” a song that merges country and rap, Martell says, “Genres are a funny little concept,” and we witness a baton being passed. More than half a century after her first album, Color Me Country, was released, defying the silos of her generation, Martell ushers in a track by the greatest performer of our time who does the same.

There are countless moments where Beyoncé gives voice to Black history while honoring the present. The second song on the album, “Blackbiird,” is obviously a cover of The Beatles’ “Blackbird.” But what many don’t know is that the song was originally penned by Paul McCartney following the Little Rock Nine integration of an Arkansas high school.“‘You were only waiting for this moment to arise’ was about, you know, the Black people’s struggle in the southern states,” McCartney explained years later. “I was using the symbolism of a blackbird.” In her rendition, Beyoncé’s velvety voice is joined by four young Black rising stars within the country music industry: Tanner Adell, Brittney Spencer, Tiera Kennedy, and Reyna Roberts. The opportunity extended to these young Black women will likely catapult their already thriving careers and introduce them to global audiences. At the end of the song, the four women’s voices come together and harmonize as they sing the line: “You were only waiting for this moment to arise.” In that moment, the lyric resonates as the affirmation that it was always intended to be: a love letter from Black women to Black women.

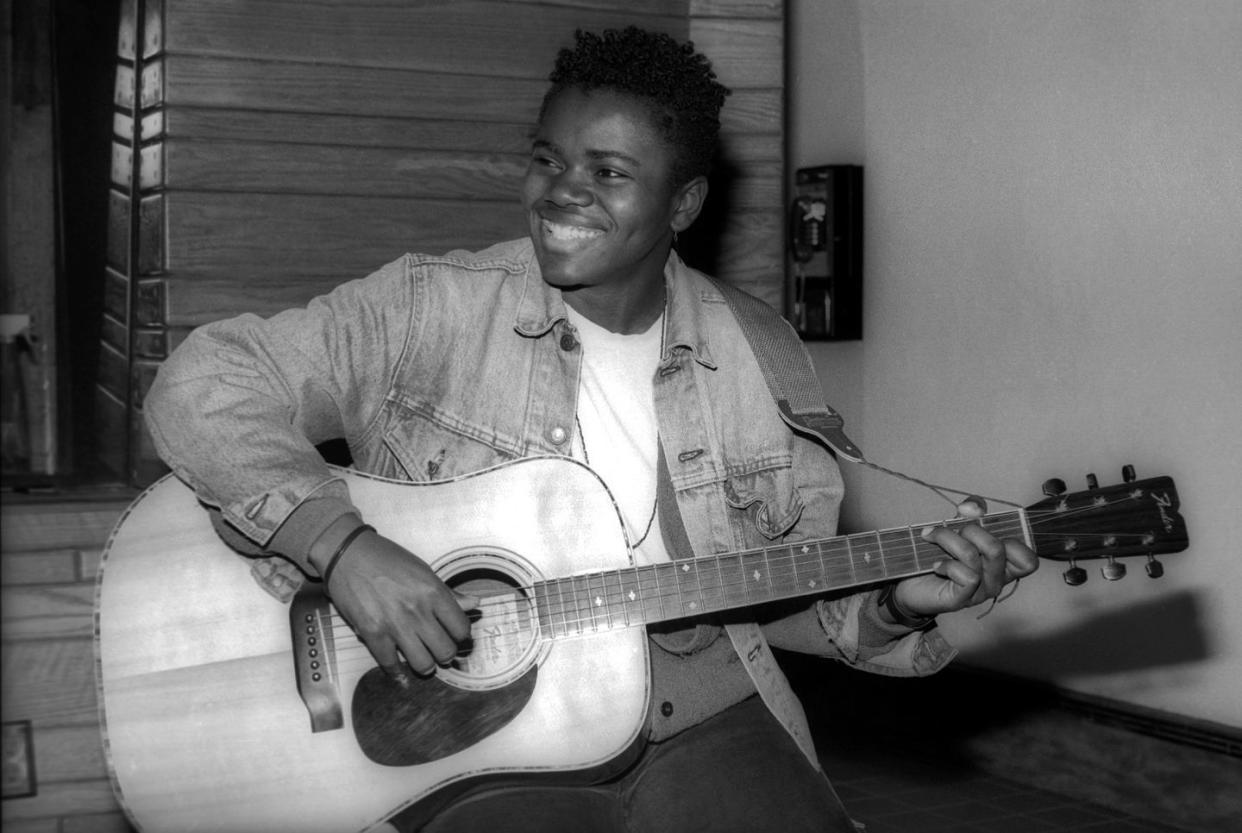

The strongest political statements of the album are made in the opener and closer, which bookend the project with powerful refrains, like, “Now is the time to face the wind,” and “I am the one to cleanse me of my father’s sins,” alluding to America’s founding fathers. Through these lines, Beyoncé seemingly calls for younger generations to take up the mantle and rebuild our society in our diverse image. Repeatedly asking, “Can you hear me?” and “Do you hear me?” Beyoncé joins the rich tradition of Black women using country to be seen and heard, à la Tracy Chapman’s “Talkin’ Bout a Revolution” and Mickey Guyton’s “Black Like Me.”

In “Ameriican Requiem,” the album’s first song, Beyoncé croons, “Them big ideas are buried here.” In the outro of that song, she continues to eulogize what America was supposed to be when she sings, “Goodbye to what has been / a pretty house that we never settled in,” referencing the unfulfilled promises of liberty and justice for all. By the end of the album, with “Amen,” Beyoncé takes a stronger stance when she says, “This house was built with blood and bone, and it crumbled.” It is inevitable for injustice to proliferate on such a rotted foundation. This nation’s wealth—the basis of the American dream—was made possible through the back-breaking work of Black people and the theft of Indigenous-stewarded land.

Long before Frederick Douglas wrote “What to a Slave Is the Fourth of July?” Black Americans have called out the hypocrisy in America’s proclaimed commitment to independence while denying that to communities of color. On “Ya Ya,” Beyoncé growls, “My family lived and died in America / Good ole USA / Whole lotta red in that white and blue, huh / History can’t be erased.” We hold a mirror up to America’s ugliness as an act of love and accountability. Beyoncé continues singing, “You lookin’ for a new America? / Are you tired, workin’ time and a half for half the pay?” This reads as an invitation: Help us build a new America that works for us all.

While some have called for new homelands elsewhere, many Black leaders have demanded our slice of this pie right here. Why should we be forced to relinquish our birthright? Beyoncé heavily leans into this idea, not only through lyrics, but also in the Americana clothing she wears in the album visuals. I was originally hoping for a less red, white, and blue aesthetic, but Beyoncé follows the tradition that many Black Southerners charted when they insisted on their right to full citizenship. It isn’t blind patriotism; it’s reclaiming our right to live and thrive here in a country we built. Taylor Crumpton, a music writer and Black Texan herself, wrote: “To be a Black Texan, you learn how to bear hatred and love in your heart at the same time.” She continues, “It is nothing short of a miracle that the Black community can carefully balance a desire to honor the cultural traditions of preceding generations with the pain embedded within those traditions.”

Beyoncé’s reclamation of a musical genre that was born of and shaped by working-class Black Southerners comes at a time when Black people across the diaspora are demanding a historic reckoning followed by restitution to the descendants of the stolen, exploited, and ignored. Elected officials from California to North Carolina are exploring local reparations projects to return stolen land to their rightful heirs. British commonwealth nations like Jamaica and Barbados are calling for restitution. Elite universities like Harvard are dedicating hundreds of millions of dollars to addressing legacies of racism. More than reflecting the times, Cowboy Carter provides the soundtrack for multiple generations of Black Americans.

When I said I didn’t like country music, what I really meant was I didn’t like fighting to find songs and musicians who look like me and reflect my experience. Thanks to Beyoncé, I now have a playlist full of Black country artists like Reyna Roberts, Shaboozey, Brittney Spencer, Tiera Kennedy, Tanner Adell, and Willie Jones—who were all featured on the album—as well as BRELAND, Ashlie Amber, Jimmie Allen, and Kane Brown, who are powerhouses in their own rights. As country singer Mickey Guyton once said, “We need to see a sea of people of color (and) Black people make it in this industry. That is how you truly find change.” In the meantime, Beyoncé is making it clear that country music isn’t a pivot for her, or the Black community, at all.

You Might Also Like