How Colorado protects wetlands depends on two perspectives: Is it a water quality issue or a land management issue?

Even assuming it's a little of both, either answer leads to different approaches, each to be overseen by a different agency.

And either path offers implications for construction, permitting and management of habitats.

This month, lawmakers looked at the dueling approaches contained in two measures seeking to implement a way for the state to manage "dredge and fill discharge" permits tied to a recent U.S. Supreme Court decision that redefined how a body of water can be protected under the Environmental Protection Agency's "Waters of the United States" rule.

Supporters of the first bill, which gives the task to the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, insist it's the proper venue because it already experience dealing with permitting and water quality issues. Supporters of the second measure, which hands the responsibility to the Colorado Department of Natural Resources, maintain that the Department of Natural Resources is better equipped, since it already deals with related disciplines, such as water resource management, water rights law and land management.

In any case, policymakers agree that Colorado residents, industries and the wetlands needs certainty.

Will a million acres of Colorado wetlands lose protection?

The proposed changes in Colorado arose out of the U.S. Supreme Court's 9-0 in May 2023 in favor of the Sacketts, an Idaho couple who bought land on which they wanted to build a home in 2004. The parcel was about 300 feet from Priest Lake, one of the state's largest. They began backfilling the lot with dirt and gravel, which earned them the attention of the EPA. The agency said the land contained a protected wetland across a paved road and was connected by a ditch and creek to Priest Lake.

The EPA blocked that development, partly because the Sacketts did not obtain a permit for dredging and filling discharge from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which manages wetlands.

The majority opinion, authored by Justice Samuel Alito, relied on a 2006 opinion in Rapanos v. United States from Justice Antonin Scalia. That viewpoint held that "any wetland that does not connect at its surface to another body of federally protected water doesn’t merit the same degree of protection."

Alito noted, "The wetlands on the Sacketts' property are distinguishable from any possibly covered waters."

The ruling's potential impact in Colorado, according to some experts, is to lose protection for nearly a million acres of wetlands.

Alex Funk with the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership told a legislative committee last August that almost 90% of fish and wildlife in Colorado rely on the state's wetlands at some point during their lifecycle.

House Speaker McCluskie told the House agriculture committee on April 8 that since Sackett v. Environmental Protection Agency held that only permanent streams and rivers are protected under the federal Clean Water Act, those with a continuous surface connection to another permanent water body.

That puts Colorado waters at risk, she said.

Pitkin County Commissioner Greg Poschman also noted that the state's headwaters are made up of small streams that do not have year-round flow because they are under snowpack half the year — suggesting Sackett would put those waters at risk.

"Many of these areas are seasonal wetlands and wet meadows," Poschman said. "These pristine headwater streams flow into the western rivers, which are the very backbone of our state's recreation, tourism, and agricultural economies. They recharge groundwater, filter pollutants, ensure clean drinking water, and reduce the risk of flood, drought and wildfire."

Another expert estimated that 45% of Colorado's streams are intermittent and 24% are short-term in their lifespan, leaving two-thirds of Colorado waters outside of "Waters of the United States" protections.

Debbie Ford, who lives in the foothills of Jefferson County near Turkey Creek and Shadow Mountain, where there are 11 designated wetlands, said Sackett took away their protections.

"Without essential protections of our water and wetlands, we jeopardize our wildlife," she said, adding wetlands provide most wildlife habitat.

The Colorado approach

While the WOTUS issue has been a concern since the Trump administration narrowed the EPA rule in 2020, after the U.S. Supreme Court Court's decision came out, Gov. Jared Polis convened a task force to figure out how Colorado should respond.

The task force considered two thoughts. One was a "gap" program that could cover any waters no longer protected by Sackett. The other was supporters called a Colorado-based approach that relied on existing state law about what defined Colorado waters and would be much simpler to operate.

In any case, Colorado is now in the position of developing its own permitting program to protect those wetlands, particularly for dredge and fill discharge permits, experts said.

That led to hearings during the week of April 8 with the two competing measures in House Bill 1379 and Senate Bill 127.

Already reviewed by the House agriculture panel, HB 1379 is sponsored by McCluskie, agriculture committee chair Rep. Karen McCormick of Longmont and Sen. Dylan Roberts of Summit County, who chairs the Senate Agriculture and Natural Resources Committee.

The other measure — Senate Bill 127, is sponsored by Sen. Barbara Kirkmeyer, R-Weld County, and Rep. Shannon Bird, D-Westminster.

Task the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment?

HB 1379 would set up a regulatory structure for dredge and fill discharge permits to be managed by the Colorado Department of Public Health & Environment.

It would cost $545,000 and require an additional 4.1 full-time equivalent employees in its first year.

Under the bill, the health and environment agency would establish rules for regulating discharged dredge and filling materials into state waters, including wetlands. Anyone discharging dredge and fill materials into a state water that doesn't have an exemption — and the list of exemptions is lengthy — would need a permit.

Funk of the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership explained that one major effect of the Sackett decision applies to the "404" permitting system under the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Those permits are used for dredging a river for navigation purposes or filling in wetlands for construction, as was the case with the Sacketts.

Colorado law only allows dredge and fill discharge activities with a current federal permit. McCluskie surmised the court decision could make these permits illegal because they are in waters no longer regulated by federal agencies.

Without a state permitting program, those engaged in dredge and fill discharges could be “left to guess” if they should move forward with those projects or risk drawing enforcement actions, she said.

“The state does not want enforcement to be the only solution to this issue,” McCluskie said.

She said the state approach under HB 1379 would be based on already-established permitting paths developed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, such as the CDPHE's longstanding permitting program for stormwater and wastewater discharges.

McCormick told the ag committee that construction partners, agriculture producers, and the conservation community need certainty — and HB 1379 will deliver that certainty.

The public health department currently manages more than 12,000 water permits under the 402 process, which applies to stormwater and wastewater discharge. About half of those 12,000 permits are for construction.

McCormick said supporters prefer the state's health and environment because of its experience in the permitting space.

But the agency also has a backlog in permit approval that has been a sore subject for years. Its system shows a backlog of almost 2,400 cases delayed or administratively "continued" permits. The backlog goes back to 2010, and several permits that expired in 2012 are still waiting on approval.

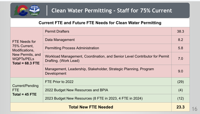

Last October, the public health department said it would need more full-time employees to pare down the backlog to get up to 75% of permits approved.

CDPHE requests for additional employees to pare down backlog on 402 permits

CDPHE backlog for 402 permits as of October 2023.

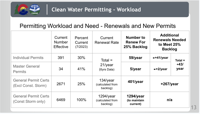

The fiscal analysis for HB 1379 estimates that about 110 projects per year would need new permits.

Or the Department of Natural Resources?

SB 127, meanwhile, would establish a stream and wetlands protection division and a commission within the Department of Natural Resources, which would create the rules for a dredge and fill discharge program.

Until then, the bill would prohibit the health and environment agency from taking enforcement actions against projects, if those projects are conducted in a manner that protects state water under the Waters of the United States rules that existed prior to Sackett.

The measure also includes enforcement provisions.

But critics of SB 127 note the natural resources department has little experience in permitting. Its primary permit program is on well water and doesn't deal with federal issues; hence, it would have to start a 404-type program from scratch.

That's a big part of why the Senate bill has such a high cost compared to the House bill: $545,000 and 4.1 full-time equivalent employees for HB 1379, compared to $3.8 million and 23.5 FTE for SB 127.

The full-time employee requirements in the latter bill includes administrative and permitting staffers.

The fiscal analysis for SB 127 also takes a different view of what would be required to handle the wetlands permits.

The analysis said the bill's staffing amounts anticipate that the new division would assume 70% of the Army Corps’ previous actions. That equates to about 18,600 hours of "determination, permitting, inspection, enforcement, consultation, and supervision work per year," the analysis said.

Bill sponsor Sen. Barbara Kirkmeyer, R-Weld County, said noted that while the public health department approves "402" permits on water quality, what the state faces after Sackett is not a water quality issue.

"We believe in a permitting process and we need one that is very similar to 404 but with the definition from Sackett," she said.

The task should go to Department of Natural Resources, she said, because that's the agency that handles floodplain administration, the state water plan, the Colorado Water conservation Board, the state engineer, well water permits and the Division of Mining. The agency also has experience in agriculture and water rights that the public health department lacks.

All those divisions work with entities that would seek those new permits, she said.

However, the Department of Natural Resources is in full support of HB 1379. Kelly Romero Heaney, deputy policy director at the Department of Natural Resources, said Monday her agency has full confidence in the public health department's ability to develop and implement a dredge and fill discharge permitting program

Water quality?

To supporters, HB 1379 offers a "direct" approach to protecting Colorado's wetlands.

Poschmann, the Pitkin County commissioner, said HB 1379 would cover all state waters not already covered by the federal permit program from the Army Corps of Engineers.

"This direct approach ensures protection of perennial, intermittent, or ephemeral streams and vital wetlands. While our riparian and riverine areas may comprise a tiny percentage of Colorado's landscapes, they're essential to our very survival and to virtually all of wildlife survival," Poschmann said.

Poschman also said those who depend on clean water from Colorado's headwaters, including its wetlands, include the 40 million people who rely on the Colorado River.

Some of the strongest support for HB 1379 came from a former EPA official.

Gene Reetz, who retired from the Environmental Protection Agency Region 8 as a senior water resource scientist and who supervised the region's wetlands protection program, said there were numerous changes in federal policies to protect wetlands and other waters throughout his time at EPA. Region 8 includes Colorado.

"I think there's considerable merit in Colorado developing its own program so that the state has some consistency and predictability in protecting water resources," Reetz told the House Agriculture, Water and Natural Resources Committee.

He said that while there hasn't yet been any studies on the effects Sackett will have in Colorado, a study in New Mexico showed 88% of that state's wetlands would be at risk, as well as 95% of its rivers — numbers that he said would likely to be close to Colorado's.

"There's incredible scientific documentation about the connectivity of our waters, be it wetlands, intermittent streams or perennial streams," Reetz said. "It's really critical that Colorado's program develop all these waters."

Or land management?

Jim Sanderson, a water attorney and Colorado Water Congress member representing agricultural and mining interests, also advocated for SB 127 and the program to be put under the Department of Natural Resources.

SB 127 contemplates a separate commission to manage the program, which is favored by the group, he said, adding, "A division that only works on these issues has a better chance of success than adding it to any other existing agency."

Adam Eckman from the Colorado Mining Association explained the logic of putting the program under the management of the Department of Natural Resources.

Eckman said the Department of Natural Resources remains the most appropriate department for the task, given its experience with related disciplines, such as water resource management, water conservation, land management, fish and wildlife management, and mining and reclamation operations.

Sanderson, the water attorney, said HB 1379, in contrast to SB 127, creates a multi-step process that he said is unnecessarily complicated.

Meanwhile, the Colorado Water Congress, which is the state's largest water advocacy organization, took a firm position opposing the bill, even with amendments.

The group supports SB 127 instead.

As written, HB 1379 could injure water rights, said Gabe Racz, a water attorney and water congress board member, claiming it would also create confusion among the regulated community and disrupt the relationship with federal programs.

Colorado Water Congress also believes the program under HB 1379 goes well beyond the scope required by Sackett, Racz said.

Adam Devoe, an environmental lawyer representing Legacy Water, said the bill proposes a scope of regulation "far beyond anything I've seen in my career, and that's 25 years as an environmental lawyer."

The regulated community is not suggesting no regulation, Devoe told the committee.

"We're suggesting that responsible policy includes drawing a line somewhere, and that line must include consideration of impacts to affordable housing, transportation and conformance with the state water plan," he said.

The other issue, Devoe said, is cost.

Viewing the less costly bill — in terms of state spending — as the better one is not the right approach, he said, adding, that an underfunded program will fail, especially one with an enormous scope, no budget, and no people to run it.

In addition, the mining association said it supports a program that will fill in the regulatory gap left by Sackett and closely mirror the previous 404 program. HB 1379, Eckman said, is inconsistent with those objectives.

Meanwhile, Earl Wilkinson, the assistant general manager of water operations for Aurora, said HB 1379 would complicate its efforts rather than support them. The city routinely performs dredge and fill activities.

The bill provides a short timeline for the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment's water quality control commission to come up with rules, administration and enforcement procedures, Wilkinson said.

He added that the measure fails to recognize Colorado's unique environmental and operational realities, while its funding is inadequate. HB 1379 also includes "vague and ambiguous language" that has caused uncertainty and confusion for the regulated community, he told the committee.

Richard Clark, an East Cherry Creek Valley Water and Sanitation District engineer, said the bill would require water providers to submit expensive plans to solidify the historic routine diversion of their decreed water rights.

"We're concerned that these rules potentially will reduce the water that can be captured and put to beneficial use," which could increase costs for all users, whether commercial, industrial, municipal, or agricultural, Clark said.

The implications for agriculture?

The other issue, which is expanding the definition of "water of the state," contrasted with what existed prior to Sackett, also has implications for agriculture, Kirkmeyer said.

That definition, located in CRS 25-8-103 (19), states that "state waters" means "any and all surface and subsurface waters which are contained in or flow in or through this state, but does not include waters in sewage systems, waters in treatment works of disposal systems, waters in potable water distribution systems, and all water withdrawn for use until use and treatment have been completed."

The expansion under HB 1379 would not exempt out agricultural ditches. It would also affect ditches that also carry municipal water, she said.

For example, in Weld County, the Farmers Irrigation and Reservoir Company, which has been around since 1902, provides water to 300,000 municipal users in northwest Denver. FRICO, as it's known, has four major reservoirs and 400 miles of canals that go from the foothills to east of Greeley. Most of its water supplies go to agriculture.

It's a major agricultural ditch through Weld County, which is the largest agriculture-producing county in the state, Kirkmeyer noted. HB 1379 doesn't provide exemptions for agriculture or for the municipal water that comes from it and would require FRICO to obtain new permits, she said.

"I believe McCluskie's bill, the way it's set up, will stop development throughout the state of Colorado," Kirkmeyer said. "We're trying to figure out how to build sustainable housing in partnerships with local governments, not how to kill development. That is not the plan. These permitting requirements that don't exempt municipal or ag waters will stall growth."

The permitting question

To Kirkmeyer, the health department should pursue its water quality mission, but "15 years behind is not acceptable for discharge permits.

"I don't know how they can look at anyone with a straight face and say they should have additional permitting process," she said.

What kind of pollution is being allowed into the rivers because of that backlog? she asked.

Addressing the permitting issue, McCluskie said the Department of Public Health and Environment has been underfunded for decades and is behind on air and water quality permits. But adequately resourced, it can meet the industry's demands, she said.

The speaker noted there have been more than 300 permit requests submitted since Sackett and, as a result of the decision, about 7.5% of them would be under state jurisdiction. McCluskie said believes HB 1379 would result in about 100 to 125 permits per year and that the five full-time employees over two years would be sufficient.

HB 1379 was changed on April 8 with a lengthy amendment to address concerns from industry players, the Colorado River District, the Colorado Stormwater Council, Ducks Unlimited, and the Colorado Water Congress, which opposes the bill.

According to the sponsors, more amendments are anticipated.

Meanwhile, the Senate Agriculture and Natural Resources Committee reviewed SB 127 on April 11.

The bill won a close 4-3 vote on Thursday with Sen. Janice Marchman, D-Berthoud, voting with Republicans to move it to the Senate Finance Committee. While its path forward is unclear, sources said they hope the bill will generate more collaborative conversations with those backing the other measure.

HB 1379 is now in front of the House Finance Committee.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices