Government Data Refute the Notion That Overprescribing Caused the 'Opioid Crisis'

The CDC’s numbers show that pain treatment is not responsible for escalating drug-related deaths.

The Federal Trade Commission, which thinks "lack of competition and contracting practices…may be contributing to drug shortages," is soliciting public comments on that subject. But when it comes to opioid pain relievers, the problem is not a lack of competition between manufacturers, wholesalers, or distributors. Shortages of these safe and effective analgesics are instead a result of tightened production quotas imposed by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), along with a recently revealed injunction against pharmacies that was part of the National Opioids Settlement.

That $26 billion settlement resolved myriad government-backed lawsuits alleging that reckless distribution of these medications produced the ongoing "opioid crisis" of escalating drug-related deaths. The DEA's steadily stricter production limits are based on the same premise. But that premise is fundamentally mistaken.

It may not be going too far to suggest that much of U.S. public health policy regarding medical treatment of people in pain is fraudulent. The authors of the opioid prescribing guidelines that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published in 2016 and 2022, for example, knew quite well that their recommendations, which resulted in widespread undertreatment and patient abandonment, did not have a sound scientific basis.

Contrary to what Tom Frieden, then the CDC's director, said in a press release introducing the 2016 opioid guidelines, prescription practices did not create the opioid crisis and are not sustaining it now. That much is clear from data published by the CDC itself.

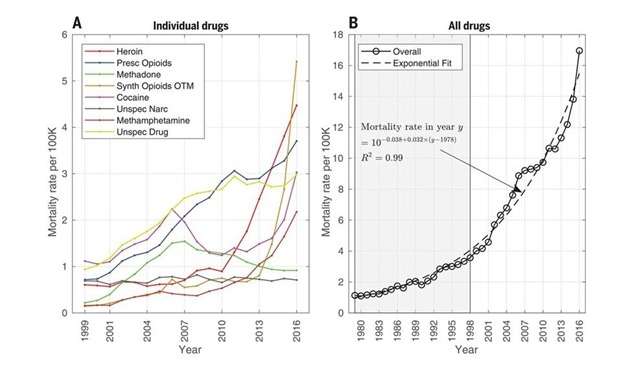

In 2018, a group of highly reputable data analysts examined about 600,000 accidental death reports spanning nearly four decades, from 1978 through 2016. They published their results in the prestigious journal Science. These charts are extracted from that study:

Although these charts might seem complicated, the most important features stand out strongly. Accidental deaths involving drugs of all kinds rose steadily and exponentially for 38 years. That period began long before the increase in opioid prescribing that is widely blamed for this trend, and it includes the seven years from 2010 through 2016, when opioid prescriptions fell by 55 percent.

The breakdown of drug-related deaths varies from year to year. But deaths involving prescription opioids—the blue line in the chart on the left, one of eight overlapping categories—have never accounted for more than 22 percent of the total.

The rise in accidental deaths since 2010 is dominated by street drugs—in particular, illegally produced fentanyl, which shows up in counterfeit pain pills as well as heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine. Legal prescriptions are lost in the noise of illicit drugs, which are often combined with alcohol. While most drug-related deaths involve multiple substances, deaths among patients who take opioids by prescription for pain relief almost never do.

The DEA has known about these data at least as far back as 2019. The agency published these charts that year as part of a course for doctors renewing their licenses to prescribe controlled substances. But this knowledge has not stopped the DEA from continuing its misguided crusade against medical providers who prescribe opioids for severe pain.

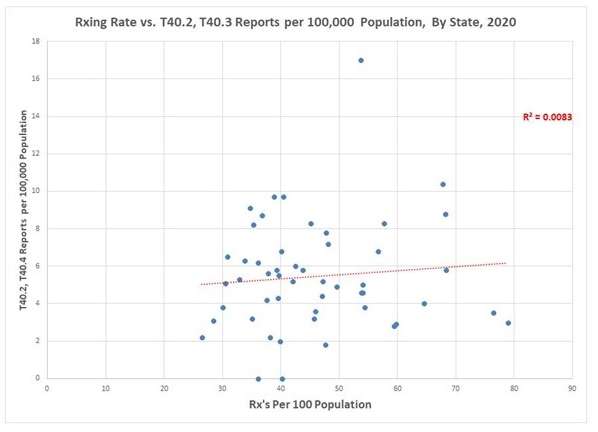

Another chart offers further insight into the sources of the "opioid epidemic." The original idea for this comparison, which is based on the CDC's mortality data and prescribing rate maps, is credited to business analyst John Alan Tucker, who published charts like this one on Twitter.

The horizontal axis shows the number of opioid prescriptions per 100 residents in each of the 50 states. The vertical axis shows the number of deaths per 100,000 residents involving either methadone (a prescription drug used in addiction treatment and sometimes for pain relief) or the "synthetic and semi-synthetic" opioids, such as hydrocodone and oxycodone, that doctors prescribe for pain.

The average number of opioid prescriptions per 100 people was about 43 in 2020. The number of death reports involving prescribed opioids was about 5.5 per 100,000. The annual risk of accidental death involving a prescribed opioid (typically along with other causes) therefore is about 1.2 per 10,000 prescriptions, or 0.012 percent. By comparison, yearly mortality from all causes among Americans 18 or older is a bit more than 100 deaths per 10,000, or 1 percent.

In other words, the risk of dying from any cause is 80 times higher than the risk of dying from an overdose involving a prescribed opioid. Most patients suffering in agony would gladly accept a one-in-10,000 annual risk of overdose in exchange for a return to their former quality of life. Several other widely accepted medical treatments have higher mortality risks.

If doctors prescribing opioids for their patients were a major driver of opioid addiction or deaths, we should see more deaths in states where prescribing rates are highest. If there were a strong cause-and-effect relationship, the data points in the chart above should be closely clumped around a line that rises from left to right. But we see neither of these patterns.

Instead, we get a splatter pattern that looks like a shotgun blast against a barn door, with no trend line. Charts for other years show the same character.

In other words, there is no consistent relationship between prescriptions and the risk of opioid overdose deaths. Other research shows that the most important risk factor is a history of severe mental health problems such as clinical depression, bipolar disorder, and suicide attempts.

The root of the opioid crisis is not pain treatment. It is instead a crisis of hopelessness driven by the conditions in which people live, including social isolation, economic distress, and a lack of meaningful prospects for a better future. Reducing the availability of pain-relieving medications or prosecuting doctors for "overprescribing" does nothing to address those problems. Yet millions of pain patients have been force-tapered to ineffective dose levels, and thousands of them are dying of medical collapse or suicide, while the DEA continues to persecute their doctors for trying to help them. It is time to evict the DEA from doctors' examination rooms.

Show Comments (82)