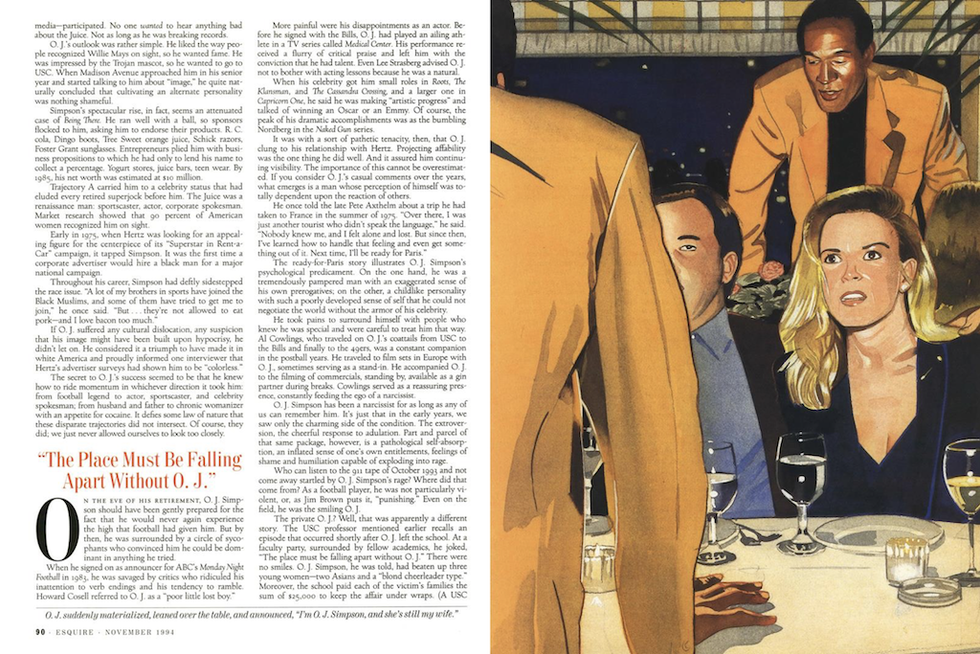

This article originally appeared in the November 1994 issue of Esquire, in the midst of the O.J. Simpson murder trial. It may contain outdated and potentially offensive descriptions of sex, ethnicity, and class. To read every Esquire story ever published, upgrade to All Access.

An accomplished liar fascinates me. So I am frankly in awe of O.J. Simpson. For the past half hour or so, I've been playing and replaying a segment of tape. Not the slow-motion freeway chase, nor the file footage of his sixty-four-yard touchdown run against UCLA, but an interview with ESPN in 1989 in which he addresses the charges of beating his wife after the infamous New Year’s Eve party.

“We were both guilty. No one was hurt. It was no big deal, and we got on with our life.”

His voice is calm and reasonable. Decency radiates from his oversize being.

The interviewer is beguiled by the Juice. He should probably have known better, but then who am I to talk? I am sitting here five years later, knowing perfectly well that it was not just some little argument between O.J. and Nicole Simpson—that he, in fact, blackened her eye, cut her lip, and kicked the wind out of her—yet I still feel a brief, visceral impulse to believe him.

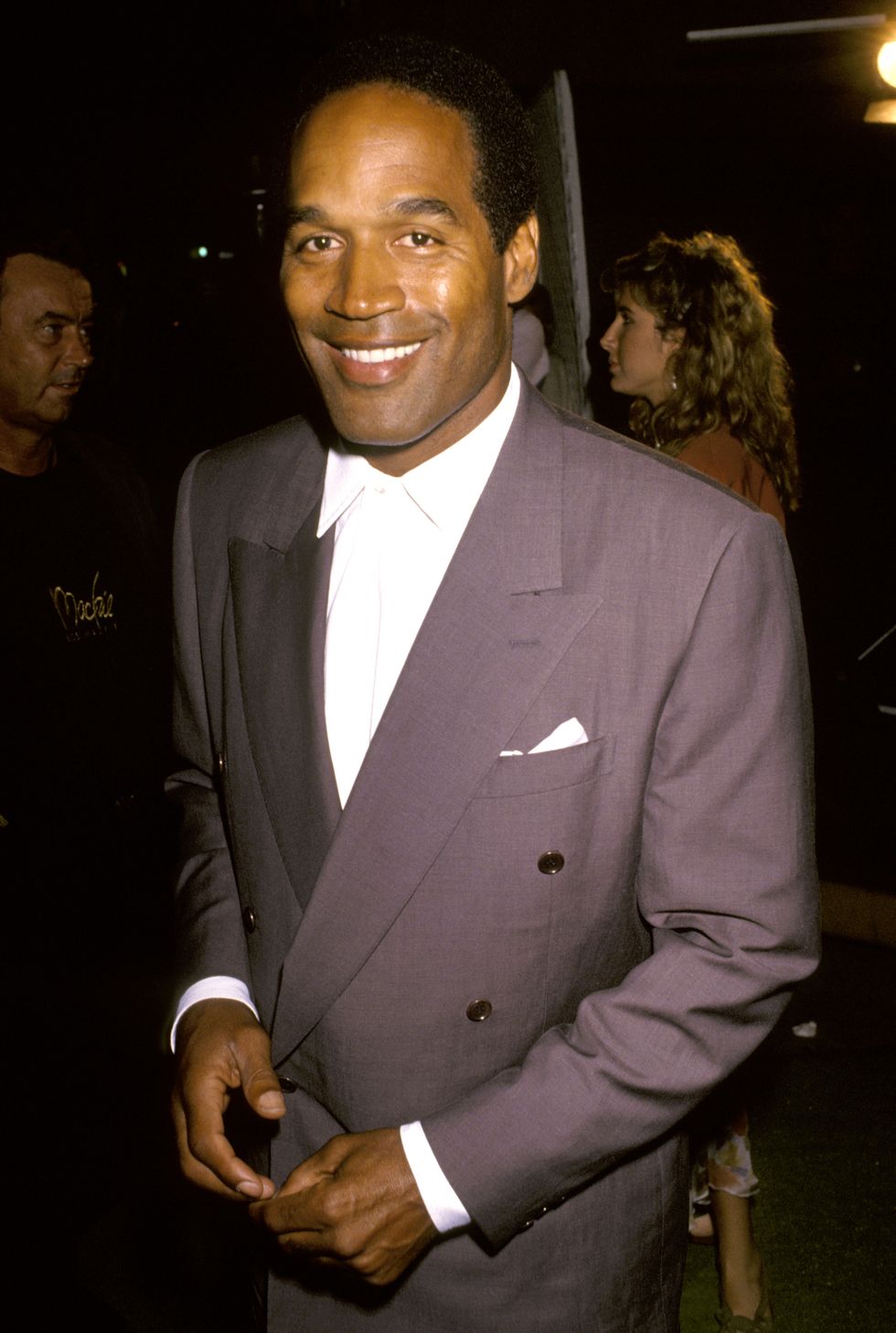

The force of habit is strong, and we have, after all, been conditioned during the past twenty-five years to regard O.J. Simpson—one of the most visible figures in American culture, one of the most splendid athletes in the history of football—as one of the nicest guys of all time. Remember the smiling O.J., quick with a quip, ready with an autograph, willing to make a joke at his own expense? In public life, O.J. Simpson made so many mercy visits to terminally ill children that he jokingly referred to himself as the Angel of Death. And he now stands accused of murdering Nicole and her young male friend, Ronald Goldman. It seems inconceivable that the Juice, the man who carried an Olympic torch, might also have crept through the night, commando style, ambushed two human beings on a garden path, and slit their throats.

“I am absolutely, one hundred percent not guilty,” he says. And there is that old impulse to believe him, an impulse checked by a rude and intrusive thought: Couldn’t a guy who lies about kicking a woman just as well lie about killing her?

Mama Simpson Holds a Prayer Meeting

Shirley Baker, O.J.’s older sister, stands on a bright floral carpet, her ample form drawn up in a posture of natural dignity. She is reading from a piece of notepaper.

“During this trying time for our family, we wish to thank all of you for your many words of encouragement, your many various floral arrangements and plants, visits, food, cards, telephone calls, your loving support along with your spiritual enlightenments. ”

Shirley continues her litany of blessings, but my attention wanders to the space around her, past an ornate white fireplace to a dining alcove, where a dozen or more longstemmed red roses rest in a vase on the table.

The living room is dim, the shades drawn—against what? Bright sunlight or a storm of scandal? Outside, dozens of well-groomed stucco homes accumulate row after row to form the black middle-class San Francisco suburb of Bayview. To the north lies the ghetto of Portrero Hill, boyhood home of the Juice.

In an easy chair near the door sits Eunice Simpson, O.J.’s mother. She is wearing an invalid’s loose clothing and a queer, peaked cap that looks to have some sort of therapeutic purpose. Eunice is convalescing from a collapse she suffered the night her son took off on his excursion in a Ford Bronco.

There are, naturally, a number of questions I would like to ask her, among them, “Mrs. Simpson, did you get along with your late daughter-in-law?”

Under the circumstances, this seems inappropriate. And probably futile. “She doesn’t hear too well,” Shirley explains. The old woman, in fact, seems only vaguely aware of what is going on around her. She is intently sorting collard greens in her lap.

I am not sure how I ended up on Mama Simpson’s couch. Back at Union Square, I hailed a taxi and gave the driver O.J.’s mom’s last known address, never for a moment thinking she’d be here. I guess I figured she would have been evacuated to quarters safe from predators from the press. But when I arrived, visitors were making their way up to the little house for a prayer meeting, and I was sort of swept in on a wave of brotherly love.

Shirley finishes reading the formal statement with a flourish. She hands me a photocopied sheet with instructions on how to send a prayer to the family. “If you refer to a scripture out of the Bible,” it reads, “please write it out.” Her eyes burn with something of a fervor, ignited either by a faith in God or a similarly strong faith in her superman brother. Her position, of course, is that the latter is innocent of the charges against him. Does she believe it?

Once, in his youth, O.J. boasted to his family, “Someday you’re gonna read about me.” To which Shirley rejoined, “In a police report.” Eunice Simpson told this story to journalists covering her son’s induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1985. Back then, it was safe to joke about how easily O.J. could have gone to the devil.

The Baddest Cat on the Hill

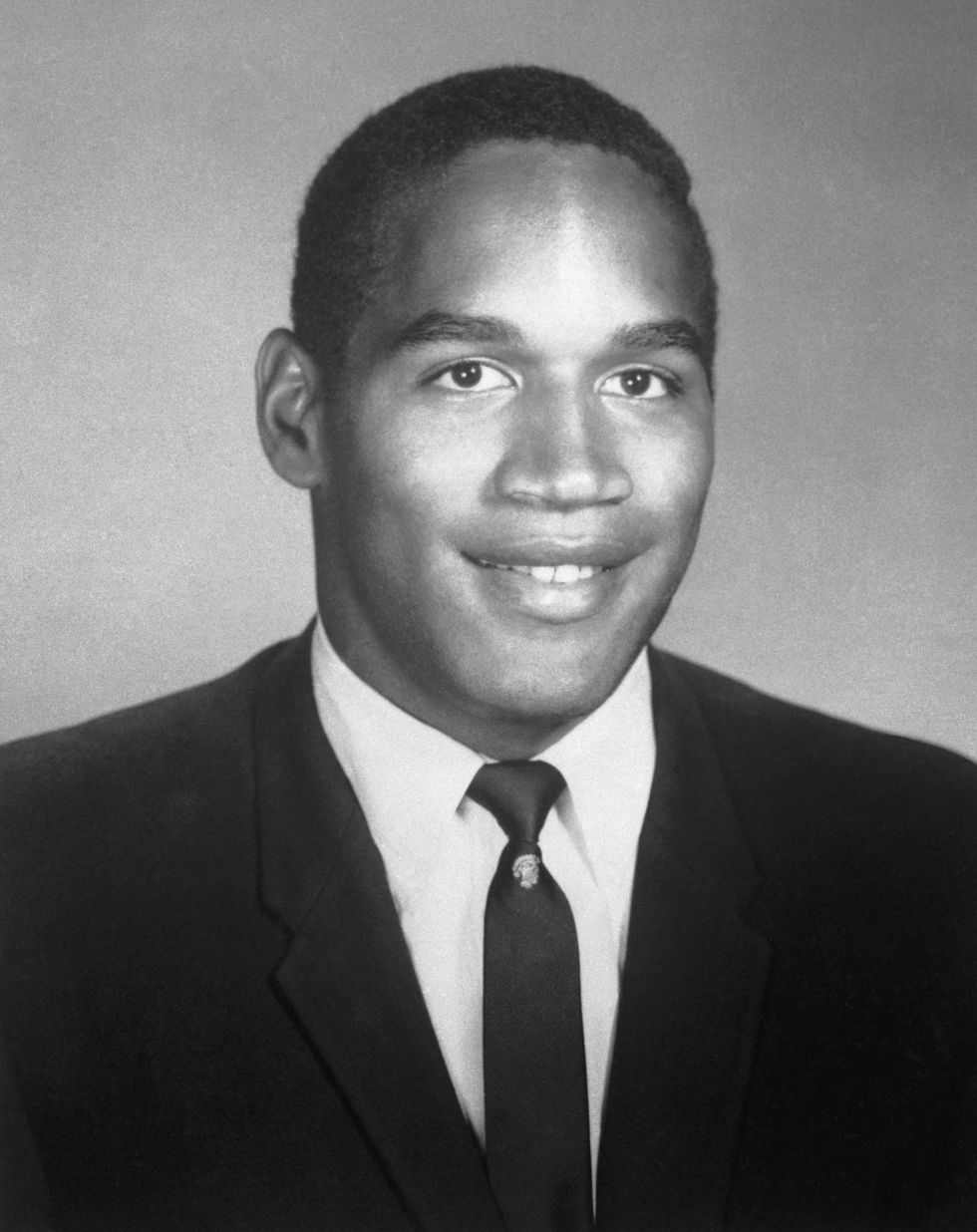

He was born Orenthal James, the namesake, it is said, of an obscure French actor. Only his mother ever called him by that peculiar appellation. To his contemporaries, he was O Jay and later O.J. or simply Juice. His father, Jimmy Lee Simpson, worked as a porter at a private club. He abandoned the family when O.J. was scarcely more than a toddler, leaving Eunice to support four children on her earnings as an orderly in a psychiatric ward.

By all accounts, Eunice displayed a fierce maternal solicitude toward the baby Orenthal, who had developed rickets soon after his birth, a condition that left him bowlegged and pigeon-toed.

“The doctors kept telling me that they should operate to straighten his legs, but I didn’t like that idea and said so,” Eunice once told a reporter. Instead, she massaged his limbs daily with oil and put him in braces (which, legend has it, she fashioned out of scrap metal). He shuffled around the house in the contraption until the age of five.

His deformed extremities earned him the nickname Pencil Pins. He was also called Headquarters and Waterhead because his head was too large for his body, making him appear hydrocephalic. In 1976, O.J. admitted to a Playboy interviewer that he had been “very sensitive” about these taunts. “But then my legs improved,” he recalled, “and I got to be a very rowdy character.”

Rowdy is a euphemism for something, though just what is now obscured by the cobwebs of mythology. O.J. would describe himself variously as a fun-loving rascal or the “baddest cat” on the Hill—depending on the public-relations needs of the moment. It is probably accurate to say he was not a hardcore hoodlum. It is also fair to assume that he was a genuinely obnoxious punk. This impression was confirmed by lifelong buddy Al Cowlings during their days at USC.

“We played a lot of sandlot football together,” Cowlings told an interviewer then. “But I never liked to play on the same team with O.J.... He was a halfway bully.... I didn’t like him then. But then, most of his closest friends today didn’t like him then, either.”

In a subsequent interview, O.J. weighed in with an equally unflattering view of A.C. “Al ran around with the submissive group,” he joked. “I ran around with a bunch of cutthroats. They didn’t want to mess with us.”

As Boyz on the Hill, the two engaged in petty larceny and extortion. “In junior high,” recalled Cowlings, “we ran our own protection agency.... We’d scout around school and find someone who was weak. Then we’d get someone to go push him around a little. After that, we’d come up and ask the kid if he needed any protection. If he said no, the same guy would come back and push him round some more. This was repeated until he paid, but we never hurt anyone.”

At fourteen or so, they joined their first “fighting gang,” the Persian Warriors. There, O.J. got his sexual initiation at the hands of the ladies’ auxiliary, the Persian Parettes. He also got busted stealing from the local liquor store. A neighborhood youth leader who thought O.J. might be salvaged persuaded Giants center fielder Willie Mays to spend an afternoon with the boy. O.J. would later cite the three hours of undivided attention from the baseball legend as the experience that changed his destiny.

It is a charming story. But O.J.’s escape from the ghetto was engineered in a more militant fashion by his mother.

Early on, Eunice Simpson had discouraged Orenthal’s interest in athletics because of his “weak bones.” But she saw he was determined, she encouraged him. When he graduated from junior high and seemed headed toward Mission High, seat of the city’s black and Latino gangs, she negotiated an athletic scholarship for her son at a parochial school, where he briefly captained the baseball team. When he cut practice to go to a dance and lost his scholarship, Eunice got him transferred to Galileo High, near the Marina, far from Portrero Hill.

By virtue of size, both O.J. and Al Cowlings were standouts on a team of small, predominantly Asian players. O.J., and by association Al Cowlings, began to attract press notice. Both were named to the all-city team, and in their senior year, O.J. led the city in scoring.

He should have been a recruiter’s dream, but his grades had been so bad that no college approached him with offers. O.J. considered the Army until a friend came back from Vietnam with a leg missing. He reconsidered and enrolled in City College of San Francisco.

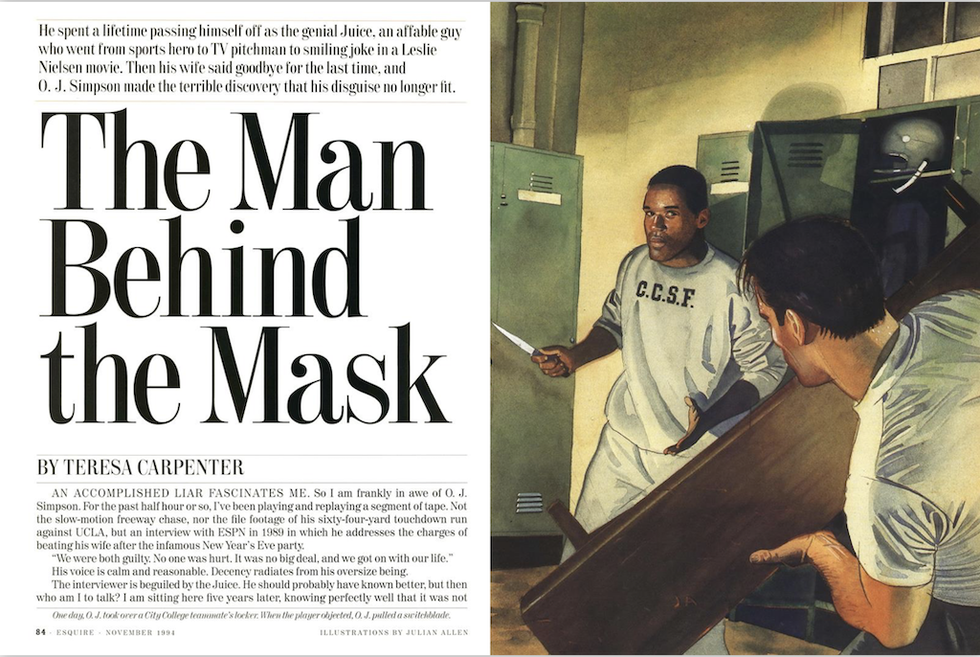

“He was careful to surround himself with people who would back him up,” recalls one of Simpson’s teammates on the City College Rams. One afternoon after practice, recalls the player, he went to his locker only to be informed by O.J. that he had taken it for his own use. When the player stood his ground, he says, O.J. pulled a switchblade. The guy claims that when he saw the knife, he picked up a bench to defend himself, whereupon O.J. backed off.

A thug in the locker room, perhaps. On the playing field, however, O.J. Simpson was an unblemished black Mercury. During his first year at City College, he averaged ten yards every time he carried the ball. CCSF players wore white helmets with red ram horns on the side. When O.J. joined the squad, a special helmet had to be ordered to accommodate his large head. It went unpainted for a few games, then he demanded it be left that way for superstitious reasons. When reporters visited CCSF, they looked for the “ghost,” whose featureless helmet seemed to mark him physically and metaphysically for a different destiny than that of his teammates. By the end of his sophomore year, O.J. Simpson had received offers from fifty colleges.

“Orange Juice” Simpson Charms ’Em at USC

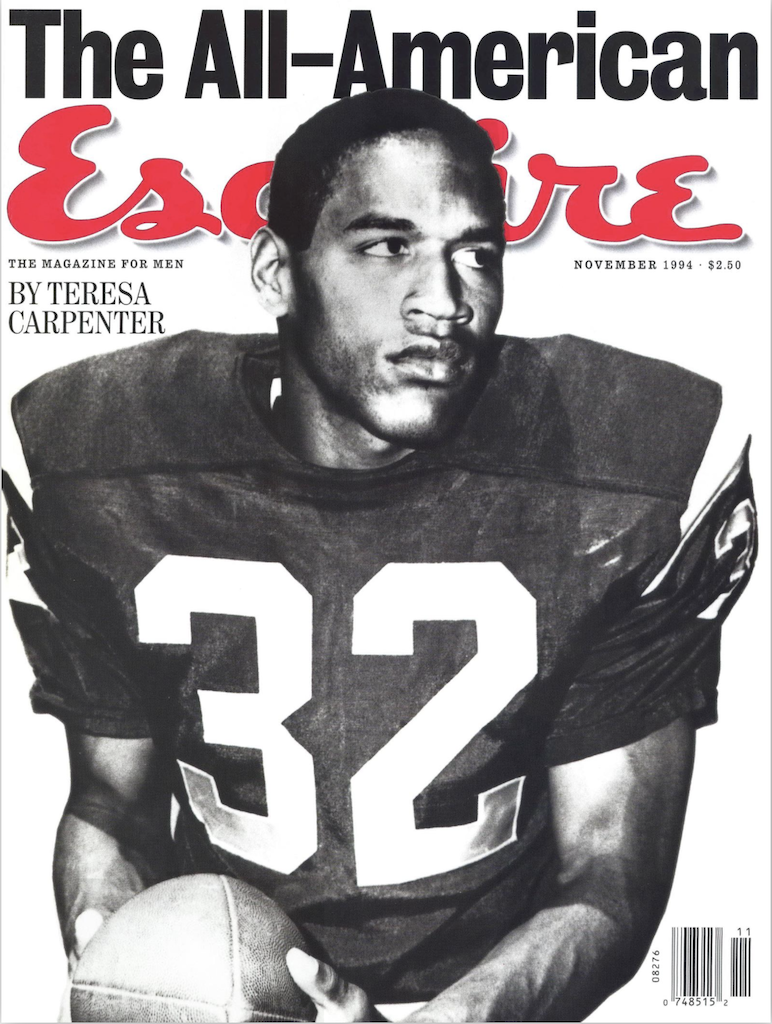

On its face, his decision to go to the University of Southern California would seem to have been made at the level of a seven-year-old awestruck by a trip to the circus. “I was really impressed,” he told one interviewer, “by that big white horse that came out on the field before their games and after touchdowns.”

There was more to it than that. A recruiter had told him that USC could give him the media exposure necessary to win a lucrative pro-ball contract. Moreover, he was aware that USC had positioned another black player, Mike Garrett, to win the Heisman Trophy.

When O.J. Simpson enrolled as a junior in the spring of 1967, the University of Southern California was a spot as distant from Portrero Hill as the planet Jupiter. A citadel of privilege, its graduates in public administration governed Los Angeles. Its doctors and technicians governed the medical establishment. The student body—overwhelmingly white and upper-middle-class—was largely immune to the social turmoil of the sixties. The school newspaper admitted that the “high cost of a USC education seems to screen out almost all Negroes. The notable exceptions to this rule are athletes admitted on scholarships.”

USC did love its football. And it was willing to clasp a “Negro” to its bosom if he could edge the Trojans toward a national championship, provided of course he demonstrate a seemly lack of interest in radical causes.

O.J. disarmed his patrons. Early in 1968, when black athletes across the country were rallying for a boycott of the Olympic games in Mexico City, the Daily Trojan described “Orange Juice” Simpson as “a sensitive, intelligent man. His environment shows through in his grammatical inconsistencies in his deep, rumbling speech, but he absorbs and understands as well as any man. He has philosophies of life and they are pretty good, but most people just like to see him lug a football. He admires Lew Alcindor, the UCLA basketball star, but disagrees with the Olympic boycott.”

“I have my philosophy,” Simpson went on to explain. “You can’t change the world until you change yourself. Once I get something concrete, something in my pocket, I can go and tell someone, ‘Look what I have done.’”

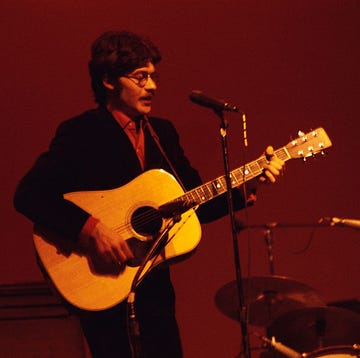

And what he did at USC was launch an athletic career characterized by moments of such intoxicating brilliance that a quarter of a century later, not even charges of murder can eclipse it.

During Simpson’s first few weeks of spring practice in 1967, USC coach John McKay lent Jay, as he called him, to the track team, on which he helped set a new world record in the 440-yard relay. Later that year, he went on to become college football’s leading rusher. Against USC’s nemesis, Notre Dame, he carried the ball thirty-eight times for 150 yards and three touchdowns. The Trojans won the national championship, and O.J., the team’s star running back, was named all-American.

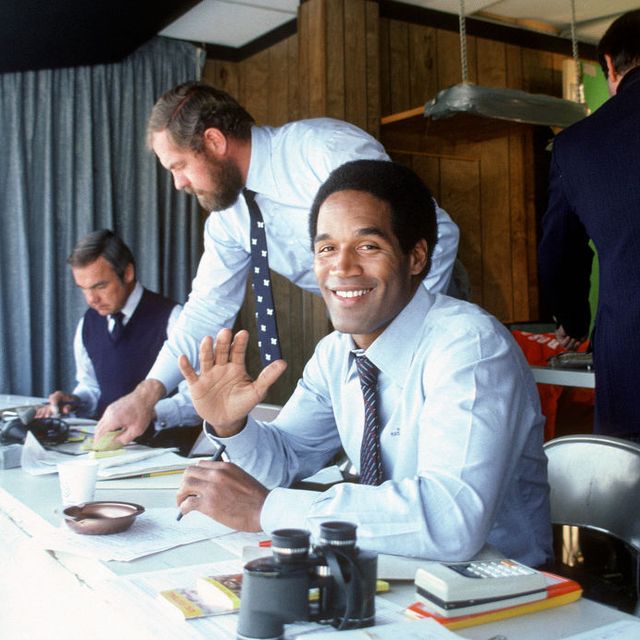

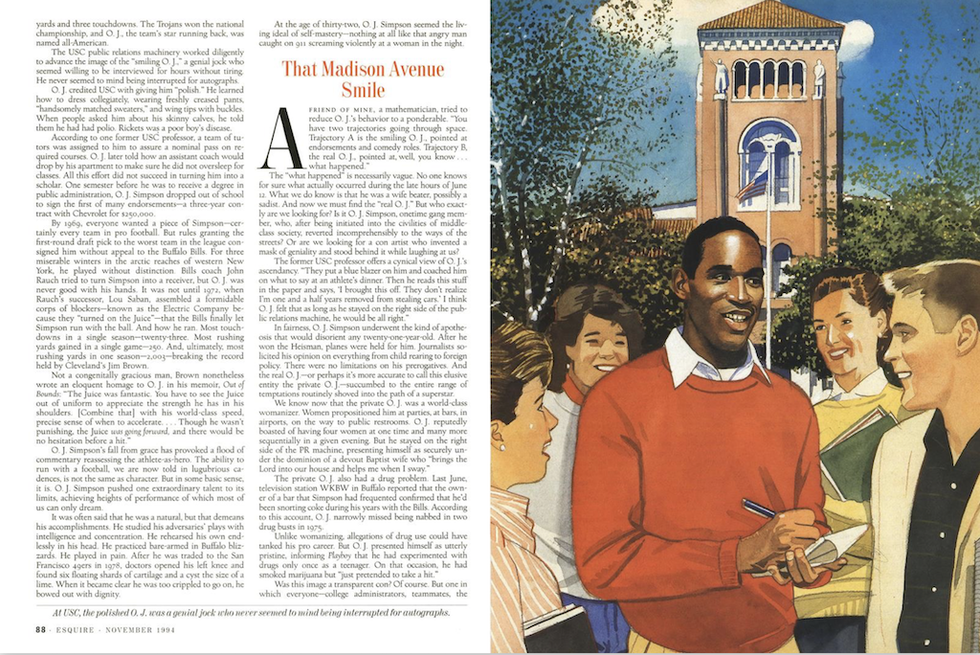

The USC public relations machinery worked diligently to advance the image of the “smiling O.J.,” a genial jock who seemed willing to be interviewed for hours without tiring. He never seemed to mind being interrupted for autographs.

O.J. credited USC with giving him “polish.” He learned how to dress collegiately, wearing freshly creased pants, “handsomely matched sweaters,” and wing tips with buckles. When people asked him about his skinny calves, he told them he had had polio. Rickets was a poor boy’s disease.

According to one former USC professor, a team of tutors was assigned to him to assure a nominal pass on required courses. O.J. later told how an assistant coach would drop by his apartment to make sure he did not oversleep for classes. All this effort did not succeed in turning him into a scholar. One semester before he was to receive a degree in public administration, O.J. Simpson dropped out of school to sign the first of many endorsements—a three-year contract with Chevrolet for $250,000.

By 1969, everyone wanted a piece of Simpson—certainly every team in pro football. But rules granting the first-round draft pick to the worst team in the league consigned him without appeal to the Buffalo Bills. For three miserable winters in the arctic reaches of western New York, he played without distinction. Bills coach John Rauch tried to turn Simpson into a receiver, but O.J. was never good with his hands. It was not until 1972, when Rauch’s successor, Lou Saban, assembled a formidable corps of blockers—known as the Electric Company because they “turned on the Juice”—that the Bills finally let Simpson run with the ball. And how he ran. Most touchdowns in a single season—twenty-three. Most rushing yards gained in a single game—250. And, ultimately, most rushing yards in one season—2,003—breaking the record held by Cleveland’s Jim Brown.

Not a congenitally gracious man, Brown nonetheless wrote an eloquent homage to O.J. in his memoir, Out of Bounds: “The Juice was fantastic. You have to see the Juice out of uniform to appreciate the strength he has in his shoulders. [Combine that] with his world-class speed, precise sense of when to accelerate.... Though he wasn’t punishing, the Juice was going forward, and there would be no hesitation before a hit.”

O.J. Simpson’s fall from grace has provoked a flood of commentary reassessing the athlete-as-hero. The ability to run with a football, we are now told in lugubrious cadences, is not the same as character. But in some basic sense, it is. O.J. Simpson pushed one extraordinary talent to its limits, achieving heights of performance of which most of us can only dream.

It was often said that he was a natural, but that demeans his accomplishments. He studied his adversaries’ plays with intelligence and concentration. He rehearsed his own endlessly in his head. He practiced bare-armed in Buffalo blizzards. He played in pain. After he was traded to the San Francisco 49ers in 1978, doctors opened his left knee and found six floating shards of cartilage and a cyst the size of a lime. When it became clear he was too crippled to go on, he bowed out with dignity.

At the age of thirty-two, O.J. Simpson seemed the living ideal of self-mastery—nothing at all like that angry man caught on 911 screaming violently at a woman in the night.

That Madison Avenue Smile

A friend of mine, a mathematician, tried to reduce O.J.’s behavior to a ponderable. “You have two trajectories going through space. Trajectory A is the smiling O.J., pointed at endorsements and comedy roles. Trajectory B, the real O.J., pointed at, well, you know... what happened.”

The “what happened” is necessarily vague. No one knows for sure what actually occurred during the late hours of June 12. What we do know is that he was a wife beater, possibly a sadist. And now we must find the “real O.J.” But who exactly are we looking for? Is it O.J. Simpson, onetime gang member, who, after being initiated into the civilities of middle-class society, reverted incomprehensibly to the ways of the streets? Or are we looking for a con artist who invented a mask of geniality and stood behind it while laughing at us?

The former USC professor offers a cynical view of O.J.’s ascendancy. “They put a blue blazer on him and coached him on what to say at an athlete’s dinner. Then he reads this stuff in the paper and says, ‘I brought this off. They don’t realize I’m one and a half years removed from stealing cars.’ I think O.J. felt that as long as he stayed on the right side of the public relations machine, he would be all right.”

In fairness, O.J. Simpson underwent the kind of apotheosis that would disorient any twenty-one-year-old. After he won the Heisman, planes were held for him. Journalists solicited his opinion on everything from child rearing to foreign policy. There were no limitations on his prerogatives. And the real O.J.—or perhaps it’s more accurate to call this elusive entity the private O.J.—succumbed to the entire range of temptations routinely shoved into the path of a superstar.

We know now that the private O.J. was a world-class womanizer. Women propositioned him at parties, at bars, in airports, on the way to public restrooms. O.J. reputedly boasted of having four women at one time and many more sequentially in a given evening. But he stayed on the right side of the PR machine, presenting himself as securely under the dominion of a devout Baptist wife who “brings the Lord into our house and helps me when I sway.”

The private O.J. also had a drug problem. Last June, television station WKBW in Buffalo reported that the owner of a bar that Simpson had frequented confirmed that he’d been snorting coke during his years with the Bills. According to this account, O.J. narrowly missed being nabbed in two drug busts in 1975.

Unlike womanizing, allegations of drug use could have tanked his pro career. But O.J. presented himself as utterly pristine, informing Playboy that he had experimented with drugs only once as a teenager. On that occasion, he had smoked marijuana but “just pretended to take a hit.”

Was this image a transparent con? Of course. But one in which everyone—college administrators, teammates, the media—participated. No one wanted to hear anything bad about the Juice. Not as long as he was breaking records.

O.J.’s outlook was rather simple. He liked the way people recognized Willie Mays on sight, so he wanted fame. He was impressed by the Trojan mascot, so he wanted to go to USC. When Madison Avenue approached him in his senior year and started talking to him about “image,” he quite naturally concluded that cultivating an alternate personality was nothing shameful.

Simpson’s spectacular rise, in fact, seems an attenuated case of Being There. He ran well with a ball, so sponsors flocked to him, asking him to endorse their products. R.C. cola, Dingo boots, Tree Sweet orange juice, Schick razors, Foster Grant sunglasses. Entrepreneurs plied him with business propositions to which he had only to lend his name to collect a percentage. Yogurt stores, juice bars, teen wear. By 1985, his net worth was estimated at $10 million.

Trajectory A carried him to a celebrity status that had eluded every retired superjock before him. The Juice was a renaissance man: sportscaster, actor, corporate spokesman. Market research showed that 90 percent of American women recognized him on sight.

Early in 1975, when Hertz was looking for an appealing figure for the centerpiece of its “Superstar in Rent-a-Car” campaign, it tapped Simpson. It was the first time a corporate advertiser would hire a black man for a major national campaign.

Throughout his career, Simpson had deftly sidestepped the race issue. “A lot of my brothers in sports have joined the Black Muslims, and some of them have tried to get me to join,” he once said. “But... they’re not allowed to eat pork—and I love bacon too much.”

If O.J. suffered any cultural dislocation, any suspicion that his image might have been built upon hypocrisy, he didn’t let on. He considered it a triumph to have made it in white America and proudly informed one interviewer that Hertz’s advertiser surveys had shown him to be “colorless.”

The secret to O.J.’s success seemed to be that he knew how to ride momentum in whichever direction it took him: from football legend to actor, sportscaster, and celebrity spokesman; from husband and father to chronic womanizer with an appetite for cocaine. It defies some law of nature that these disparate trajectories did not intersect. Of course, they did; we just never allowed ourselves to look too closely.

“The Place Must Be Falling Apart Without O.J.”

On the eve of his retirement, O.J. Simpson should have been gently prepared for the fact that he would never again experience the high that football had given him. But by then, he was surrounded by a circle of sycophants who convinced him he could be dominant in anything he tried.

When he signed on as announcer for ABC’s Monday Night Football in 1983, he was savaged by critics who ridiculed his inattention to verb endings and his tendency to ramble. Howard Cosell referred to O.J. as a “poor little lost boy.”

More painful were his disappointments as an actor. Before he signed with the Bills, O.J. had played an ailing athlete in a TV series called Medical Center. His performance received a flurry of critical praise and left him with the conviction that he had talent. Even Lee Strasberg advised O.J. not to bother with acting lessons because he was a natural.

When his celebrity got him small roles in Roots, The Klansman, and The Cassandra Crossing, and a larger one in Capricorn One, he said he was making “artistic progress” and talked of winning an Oscar or an Emmy. Of course, the peak of his dramatic accomplishments was as the bumbling Nordberg in the Naked Gun series.

It was with a sort of pathetic tenacity, then, that O.J. clung to his relationship with Hertz. Projecting affability was the one thing he did well. And it assured him continuing visibility. The importance of this cannot be overestimated. If you consider O.J.’s casual comments over the years, what emerges is a man whose perception of himself was totally dependent upon the reaction of others.

He once told the late Pete Axthelm about a trip he had taken to France in the summer of 1975. “Over there, I was just another tourist who didn’t speak the language,” he said. “Nobody knew me, and I felt alone and lost. But since then, I’ve learned how to handle that feeling and even get something out of it. Next time, I’ll be ready for Paris.”

The ready-for-Paris story illustrates O.J. Simpson’s psychological predicament. On the one hand, he was a tremendously pampered man with an exaggerated sense of his own prerogatives; on the other, a childlike personality with such a poorly developed sense of self that he could not negotiate the world without the armor of his celebrity.

He took pains to surround himself with people who knew he was special and were careful to treat him that way. Al Cowlings, who traveled on O.J.’s coattails from USC to the Bills and finally to the 49ers, was a constant companion in the post-ball years. He traveled to film sets in Europe with O.J., sometimes serving as a stand-in. He accompanied O.J. to the filming of commercials, standing by, available as a gin partner during breaks. Cowlings served as a reassuring presence, constantly feeding the ego of a narcissist.

O.J. Simpson has been a narcissist for as long as any of us can remember him. It’s just that in the early years, we saw only the charming side of the condition. The extroversion, the cheerful response to adulation. Part and parcel of that same package, however, is a pathological self-absorption, an inflated sense of one’s own entitlements, feelings of shame and humiliation capable of exploding into rage.

Who can listen to the 911 tape of October 1993 and not come away startled by O.J. Simpson’s rage? Where did that come from? As a football player, he was not particularly violent, or, as Jim Brown puts it, “punishing.” Even on the field, he was the smiling O.J.

The private O.J.? Well, that was apparently a different story. The USC professor mentioned earlier recalls an episode that occurred shortly after O.J. left the school. At a faculty party, surrounded by fellow academics, he joked, “The place must be falling apart without O.J.” There were no smiles. O.J. Simpson, he was told, had beaten up three young women—two Asians and a “blond cheerleader type.” Moreover, the school paid each of the victims’ families the sum of $525,000 to keep the affair under wraps. (A USC spokesman maintains, “To the best of our knowledge, there’s no truth to it at all.”)

It seems that O.J. was less vulnerable to a 250-pound linebacker than to perceived slights from a 120-pound woman. This fact is particularly vexing when you consider that O.J. grew up surrounded by females—his mother, two sisters, and various aunts. In an interview given during his playing years, O.J. claimed to prefer the company of women. But perhaps he just felt smothered by them.

For his mother, there is no doubt that O.J. felt a passionate devotion. “The most important person in my life,” he called her. She seemed to be his spiritual lodestar. Often, he would quote her in semibiblical terms. But their relationship was more volatile than he let on.

Eunice Simpson once told a reporter from the San Francisco Chronicle how O.J. came home one night when he was a student at City College and demanded to use the car. When she refused, she said, “He kinda raised up. So I told him one of us was going to Cypress [a local cemetery] and one of us was going to jail. I said, ‘Which is it going to be, Cypress or jail?’” O.J. retreated, and Eunice let him take the car.

According to the tabloids, O.J.’s deepest source of mortification was his father, who reputedly enjoyed a private life as a drag queen. The problem with tabloids is that even the most outrageous story usually contains a nugget of truth. And that seems to be the case here. My own canvas of the neighborhood where Jimmy Lee lived until his death in 1986 revealed that, while no drag queen, he was indeed gay. Did O.J. feel compelled to hit on every skirt that moved in order to prove his own manhood? In any event, his behavior resulted in the destruction of both of his marriages.

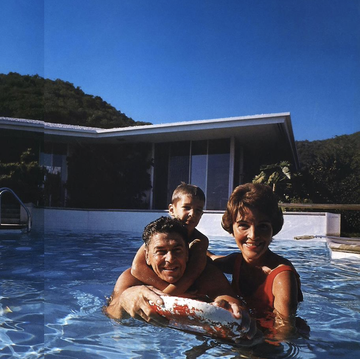

We may never learn the full scope of the indignities that O.J.’s first wife, Marguerite Whitley Simpson, suffered during her twelve-year marriage to O.J. Since his arrest last June, she has kept her silence. During the seventies, she was equally discreet, only once dropping her guard to complain that she was tired of being pushed aside by her husband’s groupies.

She was long neglected. When their first child, daughter Amelle, was born, O.J. learned of it by a note passed to him at the Heisman banquet. Marguerite, with Amelle and later baby Jason in tow, followed O.J. to Buffalo, but she hated the place. In 1975, the breach between the Simpsons became public when Marguerite stayed in Los Angeles rather than spend another winter in western New York.

There were separations and reconciliations. In May 1977, a columnist for the San Francisco Examiner reported, “Forget those rumors about O.J. Simpson’s marriage to Marguerite being on the rocks. During a recent visit here, the Juice proudly announced they will soon celebrate their tenth anniversary. ‘Why am I so proud?’ asked O.J. ‘Well, we’re expecting our third child later this year, and after that we plan to have one more.’”

Their third child, daughter Aaren, was born in September. The Simpsons moved into the $5 million Tudor mansion on Rockingham Drive in Brentwood, presumably to give their marriage a fresh start. But by September of 1978, O.J. had moved out of the house and sued for divorce. A year later, Aaren was found unconscious in the swimming pool at the Rockingham estate. The press presented the Simpsons as the picture of solidarity, together by their daughter’s bedside during the eight days it took her to die. Last June, however, People magazine quoted an unnamed source as saying that during the death vigil, O.J. ran down the hospital hall screaming, “She murdered my child.” That comment, if true, easily rises to the level of mental cruelty. Particularly if it was calculated to gain advantage. The couple was in the middle of a bitter divorce contest over assets. Marguerite hinted in court papers that O.J. played upon her guilt to get her signature on the settlement.

But did O.J. Simpson batter his first wife? Reports have surfaced of heated arguments between the two, even as far back as their dating days. One mutual friend told the San Francisco Examiner they would get into “loud, screaming fights” at parties and have to be separated.

Larry Browne and Paul Francis, authors of the quickie biography Juice: The O.J. Simpson Tragedy, report that a real estate broker surveying the Simpson’s Bel Air home after they had moved out found that it had been “rampaged, smashed, and trashed.... It looked like someone had taken out all kinds of frustrations on the house.”

But if O.J. ever inflicted physical abuse upon her, Marguerite never spoke out. Perhaps she knew it was dangerous to humiliate the Juice.

The Ghouls of West L.A.

Nicole Brown Simpson’s last address on South Bundy Drive has become a mandatory stop on the ghoul’s tour of West L.A. Two weeks after the murder, a gaggle of gawkers—composed of a pair of ladies from Buffalo, a pair of Japanese matrons from Honolulu, a young woman from the People’s Republic of China, and me—stands on the public sidewalk, peering with unabashed fascination up the tiled pathway and steps to a little pink condominium. The air is heavy with the fragrance of night-blooming jasmine, but it does not mask the smell of blood. Police have wiped the tiles clean with towels, but so much of it had already soaked into the flower beds.

For some reason, it is important for each of us to pinpoint exactly where the bodies were found. By now, we are all criminologists without portfolio and are confident that the “how” and the “who” of any case lie in the particulars.

But we cannot arrive at a consensus. It will be several weeks before I piece together enough intelligence from police reports and photos to get this tangled scene straight. Both bodies were found inside the open security gate. Nicole was resting on her left side, her back to the bottom step. She lay in a fetal position, her ankles wedged under a fence, her face turned toward the street. She wore the same black halter dress that she had worn to her daughter’s dance recital and to dinner at Mezzaluna. Her neck had been slashed so deeply that the third cervical vertebra suffered a quarter-inch nick. Goldman was discovered ten feet away from her in a small garden alcove, leaning against a palm. He died of slashes to the neck and stab wounds to his chest and abdomen. His eyes were open.

These stark elements do, in fact, suggest a how. Although there has been talk about a “second killer,” there was only a single set of bloody footprints leading from the victims to a back alley. One theory holds that the killer attacked Ronald Goldman while Nicole was still on the phone with her mother between 10:17 P.M. and 10:28 P.M. (Her Akita began its plaintive wail at 10:15.) Hearing the commotion, Nicole raced outside barefoot, only to be cut down after leaving the porch. Another school of thought: Nicole died first. The killer rang the buzzer, and she went to open the gate. Goldman may have then stumbled upon the scene as she was being murdered or shortly thereafter. Supporting this theory is the fact that Nicole’s blood was found on Ron’s boot, indicating that her blood was spilled before his. A variation on this theme is that Ron Goldman rang the buzzer, Nicole opened the gate for him, and as they were standing there, the killer descended upon them from a hiding place inside the grounds. The envelope with the glasses was found on the ground between their corpses.

A plausible how? Well, at least three of them.

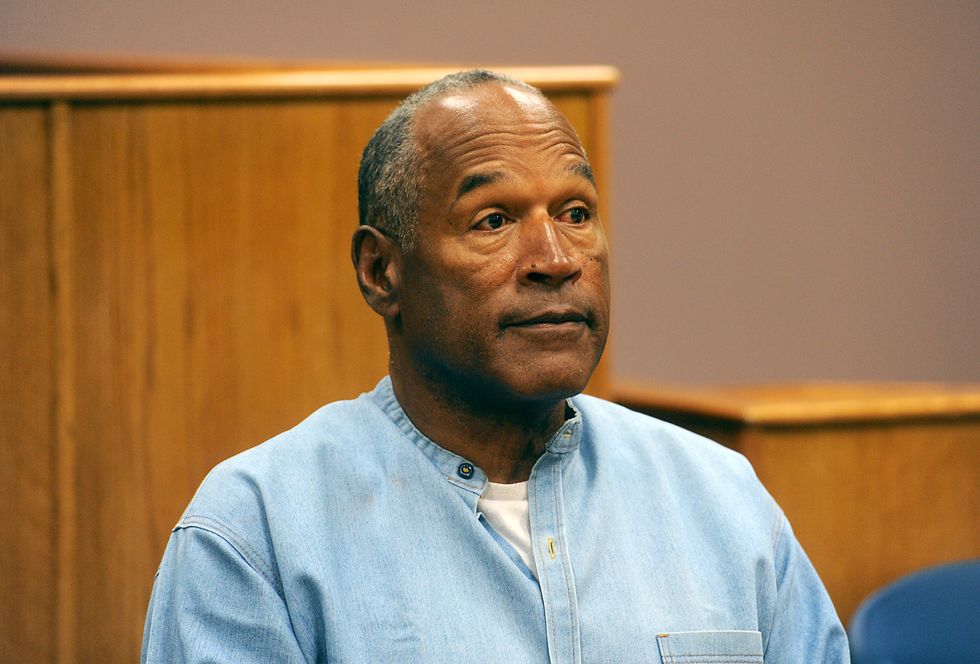

The particulars, of course, also suggest a plausible who. The trail of bloody footprints and droplets leads out of Nicole’s back alley straight to the most famous Bronco ever to roll off Ford’s assembly line, up the driveway and into the foyer of 360 Rockingham, and ultimately into the shower and sink of O.J. Simpson’s master bathroom.

What the particulars do not give us is a why, leaving us to speculate whether the carnage on South Bundy was not the predictable and inexorable end of our mathematician’s trajectory B.

Brentwood Gothic

Nicole Brown and O.J. Simpson met in June 1977, when she was waitressing at a nightclub called the Daisy. He was nearing the end of his pro-ball career. He was about to turn thirty. He was about to celebrate his tenth wedding anniversary with a woman who was then carrying their third child. And he apparently decided the future would be brighter with an eighteen-year-old white girl.

Nick, as she was known, was energetic, if lacking in direction. She had tried modeling without success and had worked as a salesgirl in a boutique for two weeks but quit without making a single sale. O.J. took as much pride in his ownership of her as he did in his vintage Rolls Silver Cloud. He chose her clothing, dictated how she should wear her hair, and insisted that she travel with him during his last year with the Bills.

Nicole Brown learned early on that she had to walk on eggshells to avoid offending O.J. Simpson. “I’ve always told O.J. what he wants to hear,” she would later say in her divorce affidavit. When she failed to anticipate his mood properly, he would snap. He would throw her out, and she would run home to her parents in Orange County. Days or hours later, he would call and woo her back. Nicole would show up in public with black eyes masked by heavy makeup. She would sometimes be indisposed for days. O.J. would attribute these episodes to “cramps.”

Nicole, like Marguerite, was galled by O.J.’s bed-hopping. He consorted publicly with an actress, Tawny Kitaen (currently cohost of America’s Funniest People). He was also a regular judge at the annual Miss Hawaiian Tropic Beauty Pageant, where he apparently regarded the contestants as his private harem. His taste ran to blondes.

When Nicole became pregnant in early 1985, however, O.J. promised to be faithful to her. The prenuptial agreement took months to negotiate and stipulated that neither party would have a claim on the other’s assets. Outmanned and outlawyered, Nicole married O.J. under a tent in the backyard of the Rockingham estate. That June, when he was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, he thanked his glowing wife for “some of the best years of my life.”

Their daughter, Sydney Brook, was bom that October 17. Nine days later, police answered a distress call at 360 Rockingham. The responding officer found Nicole sitting on the hood of her car before a shattered windshield. O.J. admitted to having broken it with a baseball bat, but he assured the officer that there was no reason to worry because “it’s mine.” During the next four years, Nicole would call police between eight and thirty times. No one knows for sure, since no charges or incident reports were ever filed. The LAPD was clearly not inclined to bust O.J. Simpson. One responding officer asked for his autograph. One of O.J.’s defense attorneys would later describe these visits as social calls. “Police that knew Mr. Simpson would sometimes come by to watch a ball game or talk to him or just visit.”

O.J.’s brutality did not enter the public record until the famous New Year’s Eve brawl of 1989. On that night, O.J. and Nicole came home from a party drunk and argumentative. Nicole, who had learned of O.J.’s affair with Tawny Kitaen only a few months before, reportedly tried to extract a New Year’s resolution from him “never to see that bitch again.” What O.J. later described as a “wrestling-type altercation” ensued.

Nicole called the police, and when they arrived, she ran from a clump of bushes in which she had been hiding and collapsed into the arms of one officer. This time, police decided to arrest.

Much has been made in recent months of the lenient treatment O.J. received at the hands of the court: a two-year probation and a $200 fine. In fact, he was shocked at finding himself on the wrong side of the public relations machine. But instead of undertaking to reform his behavior, O.J. launched a vigorous offensive to discredit his accusers. He was a celebrity being targeted by overzealous prosecutors. Either through cajoling or intimidation, he enlisted Nicole in this effort.

Shortly after the incident became public, she called Hertz CEO Frank Olsen and told him that the argument had not been a “big deal and there was nothing to it.”

Hertz stood by O.J.

“If there had been more press, we probably would have been at a different place completely,” Hertz spokesman Brian Kennedy later explained. Possibly figuring into their thinking was the fact that Nicole’s father ran a Hertz franchise, and he wasn’t complaining.

Stalking Nicole

The marriage continued its downward spiral, and drugs hastened its descent. O.J. had reportedly turned Nicole on to cocaine early in their courtship. One recovering alcoholic plugged into West L.A.’s AA circuit says members worried about the couple’s sobriety. “He was doing alcohol and coke,” she says, “and Nicole was doing cocaine and tequila. That makes for one sassy motherfucker-type woman.”

The Simpsons would have public screaming matches. One night at New York’s Sign of the Dove, O.J. reportedly followed his wife out of the restaurant while shouting, “Whore!” In another well-publicized episode, Nicole pulled up in her white Ferrari as O.J. was leaving a Beverly Hills restaurant with another woman, and screamed, “If you’re going to cheat on me, at least make it with somebody pretty.”

That their children could be shielded from this ugliness is hard to imagine. In press photos, they come across as merry little sprites. The couple’s divorce papers show that Nicole had a counselor of some kind come to the house and observe Sydney.

Nicole moved out of the Rockingham estate and filed for divorce in late February of 1992. In March or April, she made her first visit to Dr. Susan Forward, a feminist therapist and author of Men Who Hate Women and the Women Who Love Them. Forward recalls that when Nicole came in to see her, she was “haggard and trembling.” O.J., she said, had controlled every aspect of her life. He was crazy with suspicion that she had lovers, and he would hide in the bushes outside her new address to spy on her.

Forward says she urged Nicole to cut off all contact with O.J. During the next six months, Nicole distanced herself sufficiently to pursue several brief romances, one with Brett Shaves, a twenty-four-year-old paralegal at the law firm handling her divorce. When her divorce became final in the middle of October, she and Shaves vacationed in Mexico. A photo published by the National Enquirer has Shaves playfully fondling her bikini-clad breasts on the deck of a luxury condo. Seated next to them is another young man with whom Nicole had recently concluded an affair. His name was Keith Zlomsowitch.

In testimony to the aborted grand jury, Zlomsowitch identified himself as an executive with the Mezzaluna restaurant chain in California and Colorado. He had met Nicole, he said, when she was vacationing in Aspen in January 1992.

Zlomsowitch recounted how once when he had invited Nicole and a couple of her friends to the Mezzaluna in Beverly Hills, O.J. had suddenly materialized, leaning over the table and announcing in a voice that was “serious, if not scary”: “I’m O.J. Simpson, and she’s still my wife.”

On another occasion, Zlomsowitch and Nicole were dancing at a Hollywood nightclub when O.J. showed up. They left and went home to Nicole’s condominium, where they “lit a few candles” and made love on the downstairs couch. Zlomsowitch then went home. He returned the following day to find Nicole and her two children by the swimming pool. She complained of a stiff neck, he said, so they went to a bedroom off the pool—leaving the door open so that they could see the children. He sat on her back and began massaging her neck. Almost immediately, O.J. charged angrily through the back door. “I watched you last night,” he shouted. “I can’t believe you would do that in the house!” Zlomsowitch found “two vantage points” from which O.J. could have been spying on their lovemaking.

O.J.’s stalking put such a strain on the romance that it lasted less than a month. After Zlomsowitch, Nicole is reputed to have had a fleeting romance with Brian “Kato” Kaelin. (The tabloids had them cuddling in an Aspen nightclub.) Kato laid claim to Nicole’s guesthouse and ended up cast in the role of occasional baby-sitter. Later, a jealous O.J. enticed Kato out from under Nicole’s roof with an offer of free lodging at a guest cottage on the Rockingham estate.

During the months after her separation from O.J., Nicole Brown, as she preferred to be known, cut a glam figure, running errands in skintight Lycra exercise togs and working out at the gym with the muscle-bound young men of Brentwood, among them Ron Goldman.

What can you say about poor Goldman? He may have hoped to use Brown’s connections to get a restaurant going. (The defense may argue that they were financing this venture with drug money and were slaughtered by bloodthirsty Colombians.) The two nightclubbed together, and by now, of course, everyone knows of Nicole’s fondness for throwing back tequila and dancing until the wee hours. Her detractors point to this as evidence of dissolution. More likely, she was giddy after having spent fifteen years under the thumb of O.J. Simpson.

Why did Nicole surround herself with the vacuous likes of Kato Kaelin and Ron Goldman? She probably enjoyed sticking it to her ex. She probably also enjoyed being around men who were adoring and pliant and, above all, young. Regardless of the media’s fondness for portraying her as a slightly older version of the teen whom O.J. lifted from obscurity, Nicole Brown was in her mid-thirties. Her later photos betray crow’s-feet and incipient crepe neck. She was edging toward that time of life when a woman, if she is lucky, “looks awfully good for her age.” Nicole may have been in the grip of a certain desperation to recover lost years.

She did not recover them very successfully. Whatever satisfactions she enjoyed during the thirteen months of her liberation from O.J. were offset by financial worries. Although she received $10,000 a month in child support, plus a divorce settlement of more than $400,000, she was unable to sustain the life to which she had been accustomed.

In the early months of 1993, Nicole started seeing a West Hollywood therapist who suggested that her “body language” might have encouraged O.J. to hit her. She spent four sessions trying to correct that, then began intensive counseling to boost her self-esteem. At the end of it, she announced to friends, “I want my husband back.” According to Paula Barbiéri, the Victoria’s Secret model with whom O.J. occupied himself during the separation and divorce, Nicole began pursuing O.J., “writing him letters and showing up places.”

O.J. reportedly hesitated, but not for long. The divorce had humiliated him even more than his arrest for spousal battery. The degree to which he obsessed upon it became apparent during the first few days after Nicole’s murder, when, incarcerated and presumably delirious, he reported being visited by her ghost. The apparition asked, “Why?” That question, significantly, was not “Why did you murder me?” or even “Why am I dead?” but “Why did we split?” To which he replied, “It was your choice, honey.”

They began “dating” again around March 1993. O.J. was exuberant about the reconciliation, which, he doubtless felt, would set the record straight: The Juice never lost his woman. Appearing with Nicole at the opening of New York’s Harley-Davidson Cafe last October, he joked, “My girlfriend that became my wife is like my girlfriend now.” Last January, at a promotional meeting for a company called Juice Plus, he had gotten around to referring to her simply as “my wife.”

In the spring of 1993, O.J. Simpson was high in almost every respect. He, Nicole, and the children attended the premiere of Naked Gun 33 1/3. In April, he began shooting the pilot for an HBO series called Frogmen, in which he was to play a Navy SEAL commander, John “Bullfrog” Burke. O.J. seemed to be emerging from a slump, ready to take Paris by storm.

But he blew it. He continued to see Paula Barbiéri, but demanded perfect fidelity from Nicole. Only a week after the Simpsons’ joint appearance at the Harley-Davidson Cafe, O.J. kicked in the French doors of Nicole’s condo on Gretna Green Way. Nicole called 911. What triggered the incident is unclear, but O.J. had apparently fixated upon the mental image of his estranged wife making love to Keith Zlomsowitch. In the background of the 911 tape, he raves about her “giving head to Keith.”

But there was an even more insidious subtext to that tape. O.J. can be heard raving about the National Enquirer, which that week had quoted Nicole as confiding to a friend that her “heart said yes, but her head said no” to getting back together with her ex. Could it have been this fear and insecurity that led him to stalk her?

What precipitated the final breakup is not known. Browne and Francis, authors of Juice, report the Simpsons’ cook as saying that the couple had been to Spago, where a couple of men began flirting with Nicole. By the time they got home, O.J. had turned into a “vicious, terrifying monster” who tore the top of her dress and called her a “slut.”

This version has the overheated quality of a bodice ripper. A likelier scenario, supported by intelligence from the AA circuit, is that Nicole was bringing her drug-taking under control and could finally make a sober decision.

Is this the moment O.J. decided on murder? I don’t think so. I doubt that O.J., addled with ego and drugs, ever heard the word no. Right up until the end, he thought there was room to cajole, intimidate, and otherwise manipulate Nicole into a reconciliation. Whether he had the intellectual stamina to plot a murder over the period of two weeks or more has yet to be established.

A more macabre prospect is that a subconscious predisposition to murder was born weeks earlier on the set of Frogmen. Military advisers reportedly instructed the cast in the so-called silent-kill technique, in which an operative places a hand over his enemy’s nose and mouth and kicks him in the back of the knees before cutting his throat. Is it possible that O.J. Simpson’s amorphous personality took on the traits of Bullfrog Burke? He might have fantasized about killing Nicole and carried those fantasies to the point of buying a real shovel to dispose of her fantasy body. But real killing is another matter. Did something happen in the final twenty-four hours that put him over the line?

On the evening before Nicole’s murder, O.J. attended a B-list fundraiser in Bel Air with Paula Barbiéri, where he boasted about sexual conquests. That buoyant mood had dissipated by 7:00 the next morning, when he went golfing with producer Craig Baumgarten. Offended by a joking insult, O.J. threw a temper tantrum on the green. At around 2:30, Kato Kaelin saw him back at Rockingham and later testified dispassionately that O.J. informed him that he and Nicole were no longer together.

When he showed up at daughter Sydney’s dance recital at 4:00, he was calm. He and Nicole did not speak. O.J. later claimed that he had chatted with Nicole’s mother, who had invited him to come along to dinner at Mezzaluna, but that he had declined. In fact, he had received no invitation. O.J., who was used to being welcome wherever he went, may have been humiliated to have it demonstrated so publicly that he was no longer welcome in the family.

When O.J. returned home from the recital around 7:00, he climbed into his Bronco and began driving around, trying to locate his “girlfriend” on a car phone. It is not clear who this girlfriend was. Maybe Paula Barbiéri or a Playboy centerfold named Traci Adell, whom O.J. had called that day. There is an anxious quality to this pursuit. Did he drive by the Mezzaluna and watch through the large windows as Nicole and her party of ten dined en famille? He returned home at 9:15 and went out for burgers with Kato Kaelin. Kato thought O.J. looked “tired” when he left him twenty-five minutes later in the driveway of the Rockingham estate.

What did O.J. do after 9:40? The sentimental view holds that he dressed up in commando togs and toted a knife over to his ex-wife’s house, intending to slash her tires. He had reportedly done this on occasion to keep her from going out on dates. Then the arrival of Goldman propelled him into a jealous rage.

Or maybe O.J. Simpson’s mind was inflamed by a scene of a quieter sort. Earlier in the day, at the recital, he had gotten a glimpse of what the future held. Years of being snubbed by Nicole, of watching her manage to have a good time without him. Of feeling invisible in the streets of Paris. So he lashed out like a furious child.

Would You Follow O.J. into the Dark?

Had a dream about O.J. Simpson. I was wandering alone through the upstairs of an apartment or townhouse. The walls were white, the furniture white. It was twilight. I passed a nursery, which was empty. Melancholy.

From below came sounds of a party in progress, but by the time I got downstairs, the guests had left. O.J. sat on a couch, his hands clasped between his knees, his head hanging down. He lifted it and looked at me with mournful eyes. He stood and walked to a door that was open and gave a long backward look as if to say, “Trust me.” Then he walked on through it. The door remained open, an invitation to follow him into the night. And—I hate to say it—there was that visceral urge to do it, to be led blindly by an old friend.

This points out a fundamental problem in doing justice. How do you find jurors who are not old friends or don’t at least feel as if they are? No one so celebrated and beloved has ever been charged with such a crime. Is O.J. famous beyond accountability? Is he like one of those Olympian gods who periodically run amok, only to have their crimes forgiven as the foibles of the divine? If O.J. is found not guilty, will we forget that it was most likely his blood leading in precise droplets away from the bodies of Nicole Simpson and Ronald Goldman?

During the next few weeks, the defense team will be throwing about some fabulous theories about Colombian assassins, cat burglars, and mystery lovers—all in the service of raising doubt. There’s nothing seditious about this. It’s how the system works. But in this case, there is a possibility that reasonable doubt may simply be a straw that wavering jurors can clutch gratefully to let O.J. off the hook. Perhaps we should put to the defense team and jurors alike a single question: “Would you follow O.J. into the dark?”

I’d give that a no. I have seen the smiling man lie. I’ve heard the angry man screaming. No way I’m going through that door.