American popular culture would be diminished without Giancarlo Esposito, an actor whose screen presence is as lyrical as his name. The 65-year old actor has played memorable characters in many era-defining works, from the obsessives and eccentrics of Spike Lee’s early run of films to the champ’s dad in Michael Mann’s biopic Ali, federal agent Mike Giardello on Homicide, pastor Mike Cruz on The Get Down, and the omniscient narrator on Dear White People. That’s just a sample of over 200 credits since the early 1980s.

But he always popped most when playing antiheroes and bad guys, from the neighborhood gangster in the indie Fresh and a member of Christopher Walken’s crew in King of New York through his more recent turns as El Pollos Hermanos co-founder Gustavo “Gus” Fring on Breaking Bad, militia leader Tom Neville on Revolution, El Lazo on Westworld, and Moff Gideon on The Mandalorian. He brings a touch of old Hollywood elegance to these sorts of parts, whether the surrounding material is a straightforward crime story or science fiction.

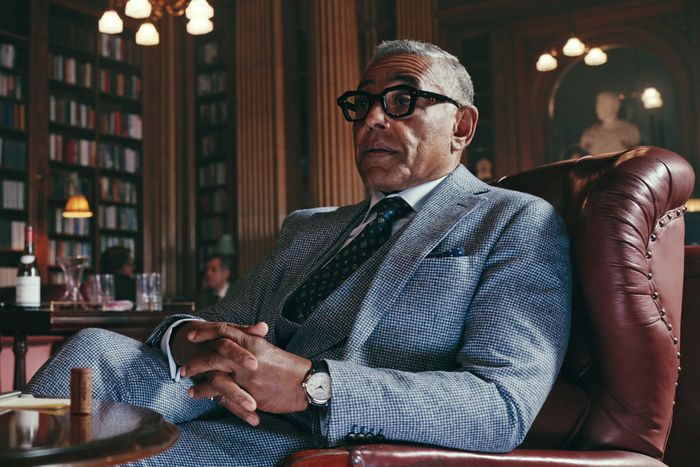

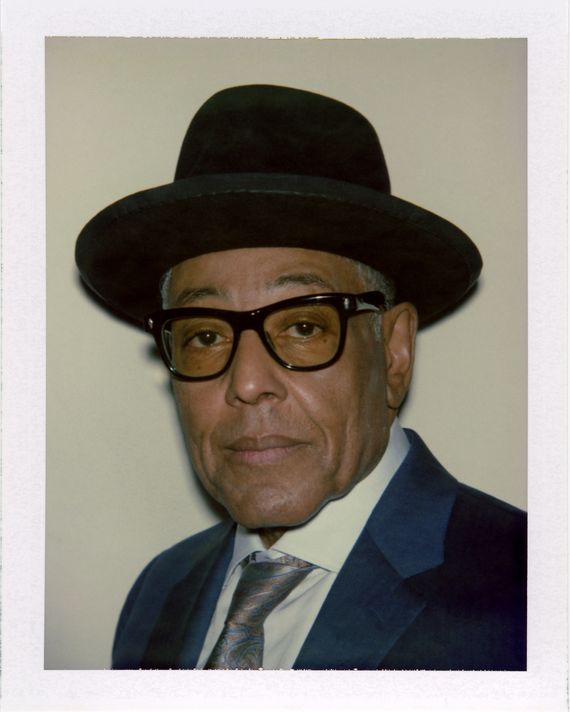

He adds two vivid portraits to the rogue’s gallery this year: the title character in the AMC series Parish, adapted from the English series The Driver, about a reluctant wheelman for African gangsters in New Orleans, and wine mogul and secret Big Bad Stanley Johnston on Guy Ritchie’s Netflix series The Gentlemen, spun off from the 2019 feature. A case could be made that these two roles are Esposito’s long-deferred reward for decades of work as a journeyman. He gets to drive (literally, in the case of Parish) the action and bury that coiled sense of menace that served him well on Breaking Bad down deep, playing it small until it’s time to go big.

As it turns out, both roles are important to him personally. Born in Denmark to an Italian stagehand father and a Black American mother who was a nightclub performer and opera singer, Esposito grew up in New York City with an intense anxiety about his family’s lack of material comfort. The persistent unease plunged him and his family into a dark place a little over a decade ago, when he overspent in order to “keep up with the Joneses,” as he puts it, and had to declare bankruptcy. He drew on that experience to play Gracián Parish, a man whose family is recovering from a recent catastrophe and up against the wall financially. But it was Esposito’s role as a member of the one percent in The Gentleman — the kind of guy who owns more real estate than some governments — that “healed” him, “because I grew up not in poverty, but pretty, pretty close to it, and it’s stuck with me my whole life.”

Can you walk me through the process of deciding to play Gray Parish?

Parish is a labor of love for me. When you are able to incorporate what you’ve lived, what you’ve experienced, then a story deepens and becomes a little more rich and a little more truthful. When we first find Gracián Parish, he’s suffering deep, deep pain from the loss of a child, and as a result has distanced himself from his family and from outer connections that allow him to feel alive. It reflects that kind of numb feeling I had when my life went off the rails in terms of being able to provide for my family and feeling like that ability was deeply connected to my manhood.

I’ve been willing to be honest and truthful about myself when I look in the mirror. Parish has lost most of his hope. He’s losing his house; he’s losing his business. I drew some comparisons to where I used to be in my ego head, in my spiritual head, and in what made me happy and what had made me happy versus where I’m at now. And I realized that there was a lot of stuff, a lot of trauma, in my own life that related to Parish.

What specific trauma are you drawing on?

I went bankrupt while I was living in Connecticut. It’s been written about a little bit, but I want to freely talk about it now because the pain of it still comes up. Pain from not being able to keep up with the Joneses, not being able to fit in within the norms of society.

How bad did things get for you?

I was thinking about suicide because I was well insured. But I would have had to have somebody kill me in order to be able to have my family get the insurance money.

This is a film-noir plot.

It is. And I think that might be a film I have to make. I gotta be honest with you: In thinking about suicide, I also realized that I love my family so much that my desperate and depressed state — Gracián Parish is depressed, too — was not allowing me to see things clearly.

I’m astonished and grateful that you’re speaking to me so openly about this period where you were contemplating self-annihilation.

I didn’t talk about this for years and years for fear of how it might look or sound, what my tragic story could have been, what the triumph of that story would have been beyond the grave after I annihilated myself.

What kind of triumph were you hoping it would be?

I was hoping that I would have been, maybe, a hero, because then my family would have enough money to invest and make money. But then they would have missed me, and I would have missed them, and I would have missed imparting all the knowledge of the struggle, of the journey, to my children.

Did you worry that killing yourself would be a cowardly thing to do?

No, because I was so connected to the idea of the hero’s journey. But this brings me to questions: What is the hero’s journey like? And what is a real, true hero? Joseph Campbell, the great mythologist, was really in cahoots with George Lucas, and Lucas knew about the mythology of the hero’s journey in relation to the Star Wars story. That hero’s journey is important for us all. But I realized that the hero’s journey is a personal journey. It’s not like the journeys you often find in fiction.

What is the hero’s journey in reality?

The world today is a society of immediacy. You’ve got to make it happen now when they call for you to pay the bills. The phone’s ringing, and if you can’t pay the rent, you’ve got 30 days to get out. But we’re also in a society where certain things look a certain way and people think they are that way.

Are you talking about that “we are a prosperous family” facade that led to your own bankruptcy, and relating it to the masked grief of the Parish family?

Yeah. Gracián Parish can cover up a lot for a certain period of time, because, you know, we’re all too busy with our phones and other objects to really look at each other and go, Oh, yeah, he’s in a good space today. Or, Oh, no, wait a minute. He’s masking. And now, when I look back on that period leading to the bankruptcy, I am thinking of the mask that I think I adopt stealthily because of the love and the finesse and attention to what I do as an actor. I practice being able to hide. I practice putting on.

The process becomes second nature. And I guess then you have to ask yourself if you’re sometimes putting on the mask even when it’s not needed for the work.

I had to realize that I don’t have to have that mask on 24 hours a day. I don’t have to convince you that I’m good at being Gus Fring or Moff Gideon or Gracián Parish. Oftentimes I talk about a character, and then I’m right back there in those moments that I live in as the character. So I have actor’s trauma!

Parish is more life-size than a lot of the other characters you’re known for.

Yes. And I should step back a second to talk about the Everyman. There’s a part of me that relates this show to the bigger picture of what I wanted to address in the work that I do. You know I’ve had a few years where I’ve played larger than life characters — some more subtly quiet and close to the vest, like Gus Fring, and others like Moff Gideon, who is someone who controls the chaos and does his own dirty work. I applaud him for that, you know. He can wield the dark saber. He can fly the TIE fighter.

What about that appeals to you?

He’s competent. He connects to that part of my life that has allowed me, and forced me, to be competent, to not be on autopilot, to not to be asleep.

And then we have Stan Edgar, the character I play on The Boys. He’s completely unflappable. He knows he’s a company man, and that’s what’s going to win in the end. And notice that he’s an adult babysitter: Part of him hates that. But all these characters, once I started to think about them, seemed to me larger than life. I wanted to pull back and tell a story of the Everyman who doesn’t recognize his extraordinary capabilities, who has to be awakened to who he really is and what he can do when he’s put in the pressure cooker. There are a lot of people in the world like that who are walking around looking at their toes, just barely making ends meet, not able to feel like they’re complete within their families unless they can really provide.

I tell my children, “You have to validate yourself.” You have to, really, and it’s hard. They’re young; they’re in their 20s. Their world is unsafe and unsure. I mention my children because I learned a lot from them, now that I’m able to hear them. Hearing with your heart is different than hearing just with your ears. Gracián wants to be in that special place where he can give his daughter driving lessons and be patient with her and have the means to send her on summer trips. He’s losing them because what he doesn’t really get is that they need him. They need him to communicate with them and be in connection to them. But he’s becoming more and more distant because the pressure is choking him. I think that represents many, many working-class people in our society today who, you know, have daydreams of robbing a bank and daydreams of becoming a meth dealer, dreams of somehow getting rich.

This show has that noir thing you’re talking about: The system is rigged, The Man’s boot is on my neck, so I might as well rob a bank because I can’t win by playing fair.

What you’re talking about makes me think about a film with Robert Ryan directed by Robert Wise called The Setup. It’s so great! It’s about this over-the-hill boxer. You know, “Just one more fight.” If he can win it, he can move up and he and his wife can start a cigar stand or invest in another boxer and live a more comfortable life. I think of the moment when he’s in the ring and he looks over at the seat for his wife, and it’s empty. He has no energy, and he’s getting the crap beat out of him. And he keeps looking, keeps hoping she will come, and she’s already said, “I can’t watch you get your brains beat out again. There’s no way you’re going to win.” All the odds are against them.

And I also think a lot about D.O.A., the original version from 1949, with Edmond O’Brien.

Incredible film. A story that puts a clock on a man’s life.

Yeah, yeah! I relate to the pressure of that, the pressure for him to do something, solve something, in a short period of time so that he can be redeemed in his own mind before he’s dead. That’s the central question characters ask themselves in these noir movies that we also get into on Parish. [In the hard-boiled yet searching style of film-noir voice-over] “Am I a good man? I have done bad things. And I’m afraid to tell you, my family, about what I’ve done. I’m hiding that. And I seem to now be returning to that. Because I want to help put food on the table, save the business. I’m ashamed to say where the money came from. How do I live with myself?”

I would bet that everybody with any kind of conscience thinks about those issues.

I would think so. You may pretend you don’t see it, even if you feel it a little bit. I think that’s kind of the way society is going. I’m trying to build a character in Parish who really feels all that.

You know, this show is based on a British show called The Driver, written by Danny Brocklehurst, starring Colm Meaney and David Morrissey. I tell you all that because in the original, which was set in England, they show you that when you’re an ex-con you have to go and see a psychiatrist. In Britain they have a points system, and this fellow is three points shy of being able to get the medication he needs, which is why he winds up in his garage hitting a heavy bag. A man in turmoil, in distress. He’s eating himself. That’s representative of a lot of people you meet in the world — people who are just so calm, but you look in their eyes and there’s something disturbing there. Right? It’s that man, that woman, that is about to break. God knows we don’t want to be anywhere near them when they do.

Is Parish that far down, in your opinion?

Parish has self-awareness, but he’s lost his faith. He’s lost that hope that God is going to bail him out or save him. So many people in our world today want to be connected to religion, to just go every week, but they’re not connected to spirituality, the purpose of which is to see the goodness in you and the goodness in me.

Is it true that you once considered being a priest?

It is true. I went to Mount St. Joseph Military Academy in Newburgh, New York. I went to Catholic schools, parochial schools. I was trained as an altar boy by priests. I was also around monks as well. So that dedication to something became important to me. I would get up every morning and I would put on my vestments before the priests got to the church. I’d frankincense the church. I’d pour the priests their wine. This is back in the ’60s when the mass was done in Latin, so there was a musicality to it. There was poetry to it. There was an organist.

What did those rituals do for your development?

They allowed me to feel soothed. I also felt like they helped other people. They helped give people hope and faith and feel there was something out there that would not only give them solace but direct their way. It was a big part of my life for a long time. And then I started to see through the cracks of the institution of the man or the woman or the nun or the priest. I started to see that they were human. They weren’t gods. They were trying to perhaps live a beatific life. I came to realize that the habit didn’t represent the woman, the nun; that vestment didn’t represent the man, the priest, or purity, or authority, but that they were flawed as well. They were human beings trying to become uplifted and be saintly. Some were hiding behind the vestments for the sake of others. I do it myself.

Everybody does.

This brings us back to the idea of masks.

We all have them.

My youngest daughter, when she was, I don’t know, 14, I said to her, “Hey, Ruby,” and she said something funny, and I went, “Hahaha!” and she looked at me and said, “Stop with the fake laugh.” She busted me. And I went, “Wow!” So now I bust myself when I catch myself performing around them.

It’s so great when your kids can understand you in that way. My kids, they see through me. I mean, through me.

I’ve got four daughters, and they see through me, too. The more real I get, the more they feel me, and the more I can share. I realized that sharing more with them, even of the painful, embarrassing, dramatic moments of life that I’ve lived, helps them to understand more about what their own lives could be about.

I never could have imagined where this interview was going to end up!

They wanted me to talk to Matt about my career, and I said, “No, I’m anxious to talk about something I’m passionate about.” I mean, what do you think? Do they owe you?

My kids?

Yes. Do your kids owe you anything?

If anything I feel like I owe them for all the shit I put them through.

How about that! How about that?

But my own parents, they had a different attitude about this stuff.

You and I grew up at a different time, where the values were different and the responsibilities were different, and as such we weren’t supposed to be really heard from until we gained enough knowledge or we were deemed adults.

Listening to you, I’m realizing how many noir films, and crime thrillers generally, revolve around people feeling as if they owe somebody something and, conversely, people feeling as if they are owed something.

It’s really funny. I was in a restaurant with my girl in California one day and asked for the check. There was no check. I had met someone on the way in who acted like she knew me. I don’t know if I ever knew her. Turns out the check was paid for by that table. It was awkward. I wondered why I felt awkward. It was just a thank you for my work. But what allowed her to feel like she should pay for my meal? Was it a gift? It all brought up this feeling that I don’t want to owe anybody anything. It also made me think of another question, which is, When are we able to accept help?

I have this other show, called The Gentlemen, from Guy Ritchie. I play one of the richest men in the world. It’s great to play that character, Stanley Johnston, because I grew up not in poverty, but pretty, pretty close to it, and it’s stuck with me my whole life, you know? That embarrassing thing where you just can’t afford things. I can remember moments with my mother and brother of eating franks and beans out of a can. Heating the can up on the stove. That was really dire. Stanley is living in England, he’s a real history buff, and he is trying to buy the main character Eddie’s mansion. He knows everything about English history, more than some Brits. But it’s that financial freedom with which he speaks. What he says is very beautifully gracious and measured. He can tell stories. He has no worries, no cares. Actually, he does: He wants something. He’s a drug dealer from America who goes to Great Britain and wants into the marijuana business and tries to buy everybody out. But what I mean to say is he’s not in that pressure cooker where Parish lives. Playing him, in a way, healed a part of that feeling in me: that I had a hole in the knee of my pants when I grew up. My sneakers were Converse All Stars because they were cheap, and I had to wear them all through the winter because I had no boots. Now I’m getting bespoke clothing made for me to play a character. I am so privileged and lucky to be able to do a thing like that. I keep doing what I do and having these experiences as an actor that expand and eradicate some of the traumatic moments I’ve had from my past. I’m able to pretend to be more than I am.

Which brings me to a line from the show that I think relates back to all this —

“I am tired of being a passenger in my own life”?

Holy shit!

That is a powerful line for me. I’m tired of being a passenger in my life. I have ideas I want to share. I want to share more with you. I want to give more. I tell my kids and I tell my students, “If you’re just a passenger, you don’t know where you’re going and you’re never gonna get there.”

Is that why you’ve played a lot of characters who are control freaks? The fear of what will happen if you allow yourself to be the passenger?

That’s right. But it’s not possible to control everything. You can only appear to.

How do you reconcile the fear of being the passenger and the counterinstinct to try to control everything?

By realizing that we all want to win, but showing up is the win. There is no win. There is no lose. Just showing up is enough, and acknowledging that you just did what you could today.